Introduction

"One who aspires to rise above all must learn to sink deep into the roots." - Veer Savarkar

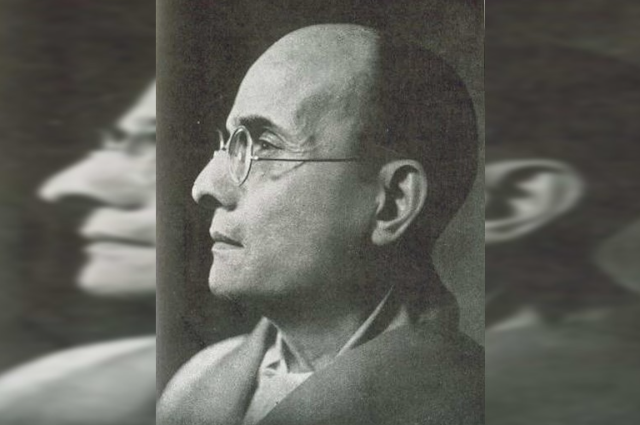

Veer Savarkar, a multifaceted personality, left an indelible mark on the Indian freedom struggle and the socio-political landscape of modern India. His life, marked by extraordinary resilience, intellectual brilliance, and unwavering patriotism, exemplifies the spirit of relentless pursuit of freedom and justice. Born as Vinayak Damodar Savarkar on 28 May 1883, in the small village of Bhagur in Maharashtra, he grew into a towering figure in Indian history, revered by many and criticized by some.

Savarkar's significance in Indian history lies in his pioneering contributions to the revolutionary movement against British colonial rule, his formulation of the Hindutva ideology, and his prolific literary output. As a young law student in London, he became a key figure in the Indian revolutionary movement, advocating for complete independence from British rule. His work "The First War of Indian Independence" shed new light on the 1857 rebellion, challenging the colonial narrative and inspiring future generations of freedom fighters. Despite enduring torturous imprisonment in the Cellular Jail of the Andaman Islands, his spirit remained unbroken, and his writings continued to inspire nationalist sentiments.

This article delves into the life and legacy of Veer Savarkar, exploring his early years and education, his revolutionary activities and subsequent imprisonment, his political ideology and contributions, his literary works, and his enduring impact on Indian society. By examining these facets, we aim to comprehensively understand a man whose ideas and actions continue to influence contemporary discourse on nationalism, secularism, and the complex history of India's struggle for independence. Through this journey, we will uncover the essence of Veer Savarkar's enduring legacy and the lessons it holds for present and future generations.

Early Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Veer Savarkar, originally named Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, was born on 28 May 1883 in the village of Bhagur, near Nashik, in Maharashtra. He belonged to a Chitpavan Brahmin family, which was known for its deep-seated cultural and religious traditions. His father, Damodar Savarkar, was a well-respected figure in the village, and his mother, Radhabai, was known for her piety and resilience. The Savarkar family valued education and instilled a strong sense of patriotism and cultural pride in their children.

Vinayak was the third of four children. His elder brother, Ganesh (fondly known as Babarao), played a significant role in shaping his early ideological leanings. Ganesh was an ardent nationalist and a fervent advocate for India's independence from British rule. The tragic loss of their parents during Vinayak's teenage years further bonded the siblings, and Ganesh's influence became even more pronounced in Vinayak's life.

Education

Schooling in Nashik

Vinayak's early education began at a local school in Bhagur, but his intellectual prowess soon became evident, prompting his family to move to Nashik for better educational opportunities. In Nashik, Vinayak attended the Shivaji High School, where his academic brilliance and oratory skills began to shine. He was particularly fond of history and literature, subjects that would later play a crucial role in his revolutionary activities and literary contributions.

During his school years, Vinayak was deeply influenced by the stories of valor and resistance against foreign rule. The tales of Shivaji Maharaj, the Maratha warrior king who fought against the Mughal Empire, particularly captivated his imagination. These stories not only fueled his nationalist sentiments but also inspired his belief in armed resistance as a legitimate means to achieve independence.

Higher Education in Pune

After completing his schooling in Nashik, Vinayak moved to Pune, a major center of learning and political activity in Maharashtra. He enrolled at the prestigious Fergusson College, where he pursued a degree in arts. It was during his time at Fergusson College that Vinayak's political consciousness began to take a more definitive shape. The atmosphere in Pune, charged with nationalist fervor and intellectual debates, provided the perfect backdrop for his burgeoning revolutionary ideas.

At Fergusson College, Vinayak came under the influence of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, one of the foremost leaders of the Indian independence movement. Tilak's call for "Swaraj" (self-rule) resonated deeply with Vinayak, who admired Tilak's uncompromising stance against British rule and his emphasis on cultural revival. Vinayak's participation in Tilak's public meetings and his exposure to the writings of nationalist leaders further solidified his commitment to the cause of independence.

Higher Education in London

In 1906, Vinayak received a scholarship to study law in London. This opportunity marked a significant turning point in his life, as it allowed him to engage with a broader spectrum of political ideas and revolutionary activities. He enrolled at Gray's Inn, one of the four Inns of Court in London, to pursue his law degree. However, his primary focus remained on the Indian independence movement.

London in the early 20th century was a hotbed of political activism, with many Indian students actively participating in discussions and activities related to India's freedom struggle. Vinayak quickly became a prominent member of the India House, a hostel for Indian students that also served as a center for revolutionary activities. He befriended like-minded individuals such as Madan Lal Dhingra, V.D. Savarkar, and Shyamji Krishna Varma, who were equally committed to the cause of India's independence.

Influences and Inspirations

Key Figures and Events

Several key figures and events during Vinayak's formative years profoundly influenced his political thoughts and actions. Among the most significant was the influence of Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Known as the "Father of Indian Unrest," Tilak's fiery speeches and writings called for immediate self-rule and galvanized a generation of young nationalists. Tilak's emphasis on using cultural symbols and festivals to mobilize the masses left a lasting impression on Vinayak, who would later employ similar tactics in his revolutionary activities.

Another major influence was the Swadeshi Movement, which advocated for the boycott of British goods and the revival of indigenous industries. The movement, which gained momentum in the early 1900s, was a direct response to the partition of Bengal by the British in 1905. The Swadeshi Movement's call for economic self-reliance and its emphasis on Indian identity resonated deeply with Vinayak, who actively participated in boycotts and protests during his college years.

During his time in London, Vinayak's exposure to European revolutionary literature and political thought further broadened his ideological horizons. He studied the works of Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary, and was inspired by Mazzini's advocacy for nationalism and republicanism. Vinayak translated Mazzini's autobiography into Marathi, hoping to inspire his compatriots with Mazzini's ideals of liberty and nation-building.

Events Shaping Political Thoughts

The partition of Bengal in 1905 by the British was a significant event that fueled Vinayak's revolutionary zeal. The partition, perceived as a divide-and-rule tactic, led to widespread protests and a surge in nationalist activities across India. Vinayak's active involvement in the protests and his participation in the Swadeshi Movement during this period marked his transition from a student activist to a committed revolutionary.

Another pivotal event was the arrest and execution of Madan Lal Dhingra, a close associate of Vinayak, for the assassination of Sir Curzon Wyllie, a British official, in 1909. Dhingra's martyrdom left a profound impact on Vinayak and reinforced his belief in the necessity of armed struggle against the British.

Vinayak's time in London also saw the publication of his seminal work, "The First War of Indian Independence," which provided a nationalist perspective on the 1857 rebellion. The book challenged the British portrayal of the rebellion as a mere mutiny and instead presented it as a well-coordinated war for independence. The publication of this book was a bold and defiant act, reflecting Vinayak's commitment to rewriting India's history from a nationalist perspective.

Revolutionary Activities

Formation of Abhinav Bharat Society

In 1904, while still a student at Fergusson College in Pune, Veer Savarkar founded the Abhinav Bharat Society. This revolutionary organization was inspired by Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy movement, which aimed to unify Italy through republicanism and nationalism. Savarkar's goal was similar: to establish an independent, united India free from British rule.

Objectives and Activities

The primary objective of the Abhinav Bharat Society was to promote armed resistance against the British Empire. Savarkar believed that achieving independence through peaceful means was unrealistic given the oppressive nature of British colonialism. Therefore, the society focused on training young revolutionaries, disseminating nationalist literature, and planning acts of defiance against the British authorities.

Members of Abhinav Bharat were trained in the use of arms and explosives, and they were encouraged to cultivate a spirit of fearlessness and sacrifice. The society's activities included organizing secret meetings, distributing pamphlets, and inspiring the youth to join the cause of armed rebellion. One of the most notable actions orchestrated by Abhinav Bharat was the assassination of A.M.T. Jackson, the District Collector of Nashik, in 1909. This act was carried out by Anant Laxman Kanhere, a member of the society, and it underscored the society's commitment to direct action against British officials.

Activities in London

In 1906, Savarkar received a scholarship to study law in London, a move that would significantly expand his revolutionary activities. He enrolled at Gray’s Inn, one of the four Inns of Court in London, with the intent of becoming a barrister. However, his primary focus remained on the struggle for Indian independence.

Participation in India House

Savarkar quickly became a central figure at India House, a hostel for Indian students in North London that also served as a hub for political activism. India House was founded by Shyamji Krishna Varma, a prominent nationalist and supporter of Indian self-rule. It attracted a diverse group of Indian students who were passionate about independence and willing to engage in revolutionary activities.

At India House, Savarkar played a pivotal role in organizing meetings, discussions, and lectures aimed at fostering nationalist sentiments among Indian students. He emphasized the importance of understanding the true nature of British imperialism and inspired his peers to join the struggle for freedom. Savarkar also facilitated the exchange of revolutionary ideas and strategies, making India House a breeding ground for radical thought.

Writing "The First War of Indian Independence" in 1909

One of Savarkar’s most significant contributions during his time in London was the writing and publication of "The First War of Indian Independence" in 1909. This seminal work challenged the British narrative of the 1857 rebellion, which the British had dismissed as a mere "mutiny." Savarkar's book reinterpreted the events of 1857 as a well-coordinated and widespread war of independence, highlighting the bravery and sacrifices of Indian soldiers and civilians.

The book was banned in India by the British authorities, but it found its way into the hands of many Indian nationalists and revolutionaries. It played a crucial role in reshaping the historical consciousness of Indians and rekindling the spirit of resistance against colonial rule. Savarkar's reinterpretation of 1857 provided a powerful ideological foundation for the revolutionary activities of the early 20th century.

Arrest and Trial

Arrest for Involvement in Revolutionary Activities

Savarkar’s revolutionary activities in London did not go unnoticed by the British authorities. In 1909, Madan Lal Dhingra, a close associate of Savarkar, assassinated Sir Curzon Wyllie, a senior British official. This high-profile assassination drew intense scrutiny towards India House and its members. Although Dhingra acted independently, the British authorities linked the act to the revolutionary activities of India House, leading to increased surveillance and repression.

In 1909, Savarkar was arrested by the British authorities on charges of sedition and conspiracy to wage war against the King. He was implicated in several plots, including the assassination of A.M.T. Jackson in Nashik. Despite his attempts to defend himself, the evidence collected by the British police, including letters, pamphlets, and testimonies from informers, painted a damning picture of his involvement in revolutionary activities.

Extradition from the UK and Trial in India

In 1910, after a prolonged legal battle, Savarkar was extradited to India to face trial. During his voyage back to India, in a dramatic attempt to escape, he leapt from the ship into the sea at Marseilles, France. He swam to shore, hoping to seek asylum in France, but was captured by the French police and handed back to the British authorities. This bold escape attempt added to his legend and demonstrated his unwavering commitment to the cause of independence.

Upon his return to India, Savarkar was tried in a series of high-profile trials. In the first trial, he was sentenced to transportation for life to the Andaman Islands, a remote archipelago in the Indian Ocean, known for its brutal penal colony. In a subsequent trial, he received a second life sentence, making his total punishment equivalent to two life sentences, or 50 years in prison.

Savarkar’s trial and sentencing had a profound impact on the Indian nationalist movement. While the British hoped that his imprisonment would deter others, it instead galvanized support for the revolutionary cause. Savarkar became a symbol of resistance and martyrdom, inspiring countless young Indians to join the struggle for independence.

Imprisonment in Cellular Jail, Andaman Islands

Savarkar was transported to the Cellular Jail, also known as "Kala Pani," in the Andaman Islands in 1911. The jail was notorious for its harsh conditions, including solitary confinement, hard labor, and inhumane treatment. Despite the severe conditions, Savarkar continued his intellectual and political work. He wrote extensively, composed poems, and smuggled out messages to his compatriots on the mainland.

During his imprisonment, Savarkar's ideas continued to influence the Indian freedom struggle. His thoughts on nationalism, Hindutva, and armed resistance were disseminated through his writings and smuggled letters. Even in captivity, Savarkar remained a potent force in the nationalist movement.

In 1924, after serving 14 years of his sentence, Savarkar was released under stringent conditions, including a ban on political activities. However, his legacy as a revolutionary leader was already firmly established. His writings and actions continued to inspire future generations of freedom fighters, making him an enduring symbol of resistance against colonial rule.

Imprisonment and Andaman Years

Conviction and Sentencing

Following his extradition from the United Kingdom, Veer Savarkar faced a series of high-profile trials in India for his involvement in revolutionary activities. In 1910, he was tried for conspiring to wage war against the British Empire and for inciting violence through his revolutionary propaganda. The evidence presented against him was substantial, including his inflammatory writings, correspondence with other revolutionaries, and testimonies from informers.

In 1911, Savarkar was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment, which in the British legal system of the time equated to 25 years. Shortly after, in a second trial related to additional charges of sedition and conspiracy, he was handed another life sentence, bringing his total sentence to 50 years. This harsh punishment was intended to serve as a deterrent to other Indian nationalists and revolutionaries. Savarkar was then transported to the Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands, a remote archipelago in the Indian Ocean known for its brutal penal colony.

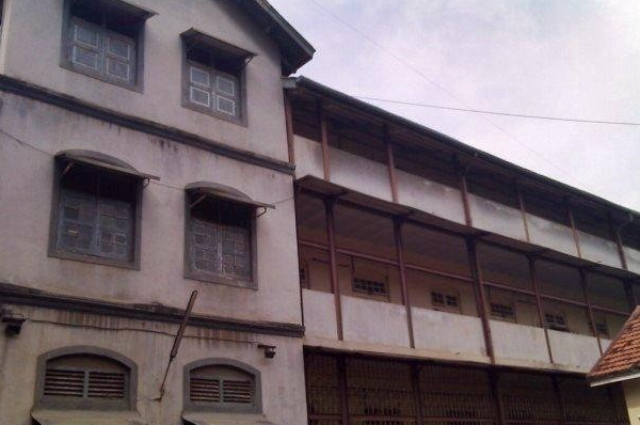

Life in Cellular Jail, Andaman

The Cellular Jail, also known as "Kala Pani," was infamous for its inhumane conditions and the harsh treatment of political prisoners. The prison was designed to isolate inmates in solitary cells, preventing communication and plotting among them. Each cell was small, dark, and poorly ventilated, creating a suffocating environment that added to the prisoners' physical and mental suffering.

Savarkar's daily routine in the Cellular Jail involved hard labor, which included tasks like breaking stones, extracting oil from coconuts, and other physically exhausting activities. The food provided was barely enough to sustain the prisoners, and medical care was virtually non-existent. Despite these severe conditions, Savarkar remained resolute and used his time in prison to continue his intellectual and political work.

Savarkar's Activities and Writings During Imprisonment

Even in the harsh confines of the Cellular Jail, Savarkar's indomitable spirit shone through. He found creative ways to continue his intellectual pursuits and to inspire his fellow inmates. Deprived of writing materials, Savarkar resorted to memorizing his compositions and inscribing his thoughts on the prison walls using thorns and charcoal. These writings were later compiled and published as "Kamala," a collection of poems that reflected his enduring hope and patriotic fervor.

Savarkar's writings during this period were not just expressions of his personal thoughts but also a means to keep the spirit of resistance alive among the prisoners. His poetry and essays covered themes of nationalism, freedom, and the cultural revival of India. He also wrote extensively on the concept of Hindutva, outlining his vision of India as a Hindu nation. These writings were clandestinely smuggled out of the prison and disseminated among Indian nationalists on the mainland, continuing to inspire the freedom struggle.

Influence on Fellow Prisoners

Savarkar's influence on his fellow prisoners was profound. Despite the severe isolation and brutal treatment, he emerged as a leader and mentor to many of the inmates. He organized secret study circles and discussions, educating the prisoners about Indian history, politics, and revolutionary tactics. His knowledge and eloquence made him a respected figure among the inmates, who looked up to him for guidance and inspiration.

Through his teachings and writings, Savarkar instilled a sense of purpose and resilience in his fellow prisoners. He encouraged them to remain steadfast in their commitment to the cause of independence and to use their time in prison for intellectual and personal growth. Many of these prisoners, upon their release, went on to play significant roles in the Indian freedom movement, carrying forward the ideas and principles imparted by Savarkar.

Savarkar's time in the Cellular Jail was marked by immense personal suffering and deprivation, but it also highlighted his unyielding commitment to the cause of Indian independence. His ability to inspire and lead even under the most adverse conditions is a testament to his extraordinary character and dedication. The legacy of his imprisonment in the Andaman Islands continues to be a source of inspiration for those who value freedom and justice.

Political Ideology and Contributions

Hindutva Philosophy - Concept of Hindutva as Outlined in His Writings

Veer Savarkar’s political ideology is best encapsulated in his concept of Hindutva, which he elaborated in his seminal work, "Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?" published in 1923. In this text, Savarkar defined Hindutva not merely as a religious identity but as a cultural and national identity. He distinguished between Hinduism, a religion, and Hindutva, which he described as the essence of being Hindu, encompassing cultural, historical, and national aspects.

Savarkar posited that India was a Hindu Rashtra (nation) by virtue of its cultural and historical heritage. According to him, Hindutva represented a collective identity that included not only Hindus by religion but also those who identified with the cultural and civilizational ethos of the land. He outlined three essential components of Hindutva: geographical unity, racial features, and a common culture. This conceptualization aimed to create a unified national identity transcending religious divisions, though it primarily centered on the Hindu identity.

Influence on Indian Political Thought

Savarkar’s Hindutva philosophy had a profound impact on Indian political thought. It provided a framework for Hindu nationalism, which influenced several political movements and parties in

India. His ideas laid the foundation for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and, later, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which adopted and propagated his vision of a Hindu-centric national identity.

The emphasis on cultural nationalism as articulated by Savarkar sought to counter what he perceived as the appeasement of minorities and the lack of a cohesive national identity. His vision resonated with many who felt that the Indian National Congress's approach to secularism did not adequately address the concerns of the Hindu majority. Savarkar's Hindutva continues to be a significant ideological force in contemporary Indian politics, shaping debates on nationalism, secularism, and cultural identity.

Role in Hindu Mahasabha - Leadership and Activities within the Hindu Mahasabha

After his release from prison in 1924, Savarkar became actively involved with the Hindu Mahasabha, a right-wing Hindu nationalist organization. He assumed leadership roles and became its president in 1937. Under his leadership, the Hindu Mahasabha sought to protect Hindu rights and interests, countering the growing influence of the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League.

Savarkar's activities within the Hindu Mahasabha included organizing conferences, mobilizing support for Hindu causes, and articulating a clear political vision based on Hindutva. He advocated for the protection of Hindu culture, the promotion of Hindi as a national language, and the establishment of a Hindu nation. Savarkar's leadership significantly bolstered the Hindu Mahasabha's influence and reach, making it a formidable force in Indian politics during the pre-independence era.

Contributions to the Ideology and Political Strategies of the Organization

Savarkar's contributions to the Hindu Mahasabha extended beyond organizational leadership to the formulation of its ideological and political strategies. He emphasized the importance of self-reliance, military preparedness, and cultural revival among Hindus. He also stressed the need for political unity among Hindus to counteract the perceived threats from the Muslim League's demand for Pakistan and the Congress's policies, which he saw as overly accommodating to minority interests.

Savarkar's strategic vision included fostering Hindu unity by overcoming caste divisions and promoting social reforms to strengthen the Hindu community. His insistence on a strong, united Hindu front aimed to ensure that Hindu interests were adequately represented in the political landscape of an independent India. These strategies and ideological underpinnings shaped the Hindu Mahasabha's actions and policies during his tenure.

Critique of the Indian National Congress

Differences with the Congress Party’s Approach to Independence

Savarkar’s relationship with the Indian National Congress was marked by significant ideological differences and critiques. While the Congress, under leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, advocated for a secular, non-violent struggle for independence, Savarkar was a proponent of militant nationalism and believed in the necessity of armed resistance to achieve freedom. He viewed the Congress's emphasis on non-violence and civil disobedience as ineffective and overly idealistic in the face of British oppression.

Savarkar also criticized the Congress for its approach to minority appeasement, particularly towards Muslims. He felt that the Congress's policies were skewed in favor of minority rights at the expense of Hindu interests. This critique became more pronounced with the rise of the Muslim League and its demand for a separate Muslim state, which Savarkar vehemently opposed.

Position on Partition and Secularism

Savarkar was an ardent critic of the Partition of India. He opposed the idea of creating Pakistan, arguing that it would lead to the balkanization of India and weaken the nation. He believed that India should remain a united Hindu Rashtra where all citizens, irrespective of their religion, identified with the Hindu cultural ethos. Savarkar's opposition to Partition was rooted in his vision of an undivided India with a strong Hindu identity.

Regarding secularism, Savarkar had a fundamentally different view compared to the Congress leaders. While the Congress espoused a secular state that treated all religions equally, Savarkar’s conception of secularism was more about the cultural and civilizational unity of India under a Hindu framework. He argued that the true essence of Indian secularism could only be achieved by acknowledging the primacy of Hindu culture, which he believed was inclusive and tolerant by nature.

Literary Works and Contributions

Major Works

Overview of Significant Writings: Veer Savarkar was not only a revolutionary leader but also a prolific writer whose literary works have had a lasting impact on Indian thought and culture. Some of his most significant writings include:

1. "Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?" (1923)

This seminal work laid the foundation for the Hindutva ideology. In this book, Savarkar expounded on the concept of Hindutva, defining it as the cultural and national identity of India. He distinguished it from Hinduism, which he considered a religion, while Hindutva was seen as encompassing a broader cultural and civilizational identity. The book argued for a unified Hindu identity, transcending religious boundaries, and called for the recognition of India as a Hindu Rashtra (nation).

2. "My Transportation for Life" (1950)

This autobiographical work recounts Savarkar’s experiences during his imprisonment in the Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands. The book provides a detailed and personal account of the harsh conditions, the inhuman treatment of prisoners, and the resilience and spirit of the freedom fighters incarcerated there. It is a poignant narrative that highlights the sacrifices made by those who fought for India’s independence.

3. "The First War of Indian Independence" (1909)

Originally written in Marathi as "1857: चे वातं यसमर," this work is a historical analysis of the 1857 uprising, which Savarkar termed the First War of Indian Independence. Contrary to the British portrayal of the event as a mere mutiny, Savarkar argued that it was a coordinated and widespread struggle for freedom. The book emphasized the heroism of the Indian soldiers and civilians who participated in the revolt.

Impact and Reception of His Literary Works

Savarkar’s literary works had a profound impact on Indian society and the nationalist movement. "Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?" became a foundational text for the Hindutva ideology, influencing numerous political movements and organizations, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). His reinterpretation of the 1857 uprising as the First War of Indian Independence provided a new historical narrative that inspired future generations of freedom fighters.

"My Transportation for Life" offered an intimate glimpse into the struggles and resilience of the revolutionaries, strengthening the resolve of many who were fighting for India’s independence. The book’s vivid descriptions of prison life and the indomitable spirit of the prisoners resonated deeply with readers and underscored the sacrifices made in the pursuit of freedom.

Contribution to Marathi Literature

Savarkar’s Role in Enriching Marathi Literature

Veer Savarkar’s contributions to Marathi literature are substantial and multifaceted. He was a versatile writer, poet, and playwright who enriched Marathi literature with his diverse works. His writings in Marathi include historical analyses, poetry, plays, and essays, all of which reflect his deep love for his motherland and his commitment to social and political reform.

Savarkar’s literary output in Marathi was characterized by a strong nationalist fervor and a call for social awakening. His works often sought to instill a sense of pride and unity among his readers, urging them to participate in the struggle for independence and the cultural revival of India.

Notable Literary Works and Themes

- "Kamala" (Poetry Collection): Composed during his imprisonment in the Cellular Jail, "Kamala" is a collection of poems that Savarkar memorized and later transcribed. These poems reflect his enduring hope, patriotic zeal, and deep emotional turmoil during his incarceration. They are imbued with themes of sacrifice, resilience, and the longing for freedom.

- "Gomantak": This play, written in Marathi, addresses the issues of caste discrimination and social injustice. Through its narrative, Savarkar advocated for the eradication of untouchability and the promotion of social equality. The play highlights his progressive views on social reform and his commitment to creating a just and inclusive society.

- "Sanyasta Khadga": Another significant play by Savarkar, "Sanyasta Khadga" (The Sword Sacrificed) explores the theme of renunciation and duty. It delves into the moral dilemmas faced by a warrior who is torn between his duty to his family and his obligation to his country. The play is a powerful commentary on the importance of self-sacrifice and duty towards the nation.

- "Majhi Janmathep": This autobiographical work, also known as "My Transportation for Life" in Marathi, provides a detailed account of Savarkar’s experiences during his imprisonment. It is a poignant and powerful narrative that sheds light on the brutal conditions in the Cellular Jail and the resilience of the political prisoners.

Themes in Savarkar’s Marathi Literature

Savarkar’s Marathi literary works are marked by several recurring themes, including:

- Nationalism and Patriotism: His writings are infused with a deep sense of national pride and a call to action for the liberation of India.

- Social Reform: Savarkar’s works often address issues of social inequality, caste discrimination, and the need for progressive reforms.

- Sacrifice and Resilience: Many of his poems and plays highlight the sacrifices made by individuals for the greater good and the resilience needed to overcome adversity.

- Cultural Revival: Savarkar emphasized the importance of reviving India’s cultural and historical heritage as a means of fostering national unity and pride.

Later Years and Legacy

Post-Independence Activities:

Involvement in Post-Independence Politics

After India gained independence in 1947, Veer Savarkar remained an influential yet controversial figure in Indian politics. Despite the ban on his political activities being lifted, Savarkar did not assume any formal political office. Instead, he continued to advocate for his vision of Hindutva and a unified Hindu nation. He remained associated with the Hindu Mahasabha, though its influence had waned significantly post-independence.

Savarkar's post-independence activities included writing, giving speeches, and engaging in public debates. He emphasized the need for a strong defense policy and was critical of India's approach to foreign policy and internal security under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Savarkar was a vocal opponent of what he saw as the Congress's appeasement policies towards Muslims and other minorities, arguing that these policies weakened the nation's unity and integrity.

Relationship with Contemporary Political Figures

Savarkar had complex and often strained relationships with contemporary political figures. He was highly critical of Mahatma Gandhi’s approach to non-violence and his policy of accommodating Muslim interests, which Savarkar believed compromised Hindu unity. His relationship with Nehru was also contentious, particularly due to their divergent views on secularism and nationalism. While Nehru envisioned a secular state that treated all religions equally, Savarkar's Hindutva philosophy prioritized Hindu cultural supremacy.

Despite these differences, some leaders respected Savarkar’s contributions to the freedom struggle. However, his radical views on Hindu nationalism and the controversies surrounding his later years made it difficult for him to forge lasting alliances with mainstream political leaders.

Controversies and Criticisms:

Criticisms and Controversies Surrounding His Political Views and Actions

Savarkar’s political views and actions have been a subject of intense debate and controversy. His advocacy for Hindutva and his stance on Hindu-Muslim relations have been criticized for fostering communal division. Critics argue that his vision of a Hindu nation marginalized religious minorities and contributed to communal tensions in India.

Additionally, Savarkar's views on social reform, while progressive in terms of caste discrimination, have been critiqued for not addressing the broader issues of economic and social justice comprehensively. His emphasis on militant nationalism and the use of violence for political ends also drew criticism, particularly from those who supported Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence.

Allegations of Involvement in Mahatma Gandhi's Assassination and Subsequent Trial

One of the most significant controversies in Savarkar's life was his alleged involvement in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Nathuram Godse, Gandhi’s assassin, was a former member of the Hindu Mahasabha and a follower of Savarkar. This connection led to allegations that Savarkar had conspired in the assassination plot.

In 1948, Savarkar was arrested and tried for his alleged involvement in the conspiracy to assassinate Gandhi. During the trial, the prosecution argued that Godse and his accomplices were influenced by Savarkar’s extremist views. However, due to lack of concrete evidence directly linking Savarkar to the conspiracy, he was acquitted.

Despite his acquittal, the association with Gandhi’s assassination tainted Savarkar’s legacy. Many continued to believe in his moral, if not legal, culpability, which cast a long shadow over his contributions to the Indian independence movement.

Legacy and Memorials

Evaluation of Savarkar's Impact on Modern India

Veer Savarkar’s legacy is multifaceted and continues to evoke strong reactions. On one hand, he is celebrated as a fierce patriot, a prolific writer, and a pioneer of the Hindutva ideology that continues to influence Indian politics. His reinterpretation of the 1857 uprising as the First War of Indian Independence and his literary contributions to Marathi and Indian literature are significant aspects of his enduring legacy.

On the other hand, his views on Hindutva and his association with communal politics have made him a polarizing figure. Critics argue that his ideology contributed to the communal divide in India, while supporters view him as a visionary who laid the groundwork for a strong, culturally cohesive nation.

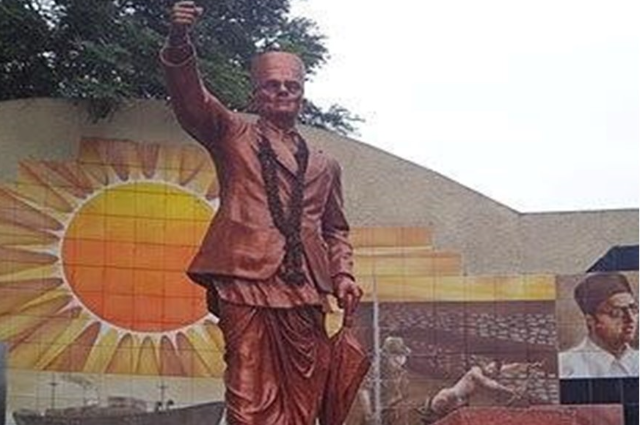

Memorials, Institutions, and Awards Named After Him

Savarkar’s contributions have been commemorated in various ways across India. Numerous memorials, institutions, and awards bear his name, reflecting his influence and legacy. Some notable examples include:

- Savarkar Memorial (Savarkar Smarak) in Mumbai: This memorial houses a museum dedicated to his life and work, including his writings, photographs, and personal belongings.

- Veer Savarkar International Airport in Port Blair, Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Named in his honor, this airport signifies his connection to the Cellular Jail where he was imprisoned.

- Savarkar National Memorial in Andaman: Located within the Cellular Jail complex, this memorial commemorates his years of imprisonment and his contributions to the freedom struggle.

- Educational Institutions: Several schools and colleges across India are named after Savarkar, promoting his ideals and teachings.

- Veer Savarkar Award: This award is given to individuals who have made significant contributions to the field of nationalism and social service, reflecting the values Savarkar championed.

Conclusion

Veer Savarkar remains a towering yet contentious figure in Indian history. His unwavering commitment to India's independence, his profound contributions to literature, and his formulation of the Hindutva ideology have left an indelible mark on the nation. While his legacy is celebrated by many for his patriotism and vision, it is also scrutinized for its communal undertones and association with controversial events. Savarkar's life and work continue to influence and provoke debate, reflecting the enduring complexity and significance of his contributions to India's cultural and political landscape.

. . .

References:

- Savarkar, V.D. (1923). *Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?* Bharat Prakashan.

- Savarkar, V.D. (1950). *My Transportation for Life*. Maharashtra Prantik Hindusabha.

- Savarkar, V.D. (1909). *The First War of Indian Independence*. Marathi Publishing House. 4. Tuteja, K.L. (2003). "Veer Savarkar and the Historiography of the 1857 Rebellion." *Economic and Political Weekly*, 38(19), 1859-1865.

- Keer, D. (1988). *Veer Savarkar*. Popular Prakashan.

- Sarkar, S. (1989). *Modern India 1885–1947*. Macmillan.

- Jaffrelot, C. (1996). *The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics*. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- Godbole, S. (2004). *Veer Savarkar Father of Hindu Nationalism*. Allied Publishers.

- Noorani, A.G. (2002). *Savarkar and Hindutva: The Godse Connection*. LeftWord Books. 10. Sharma, J. (2003). "Savarkar and the Hindu Nationalist Political Imagination." *Modern Asian Studies*, 37(2), 395-430.

- Bhatt, C. (2001). *Hindu Nationalism: Origins, Ideologies and Modern Myths*. Berg Publishers.

- Varshney, A. (2002). *Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life: Hindus and Muslims in India*. Yale University Press.

- Nussbaum, M.C. (2009). *The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future*. Harvard University Press.

- Deshpande, G.P. (1998). "Savarkar and Hindutva: The Politics of Appropriation." *Social Scientist*, 26(9/10), 40-53.

- Puniyani, R. (2003). *Religion, Power & Violence: Expression of Politics in Contemporary Times*. Sage Publications.