Introduction

In the dusty corridors of Bihar’s Animal Husbandry Department, a scandal of staggering proportions unfolded in the early 1990s—an elaborate web of corruption that siphoned off nearly ₹950 crores meant for cattle fodder, medicines, and equipment. Dubbed the Fodder Scam, this massive embezzlement scheme implicated over 500 individuals, from bureaucrats to politicians, and forever changed the political landscape of Bihar.

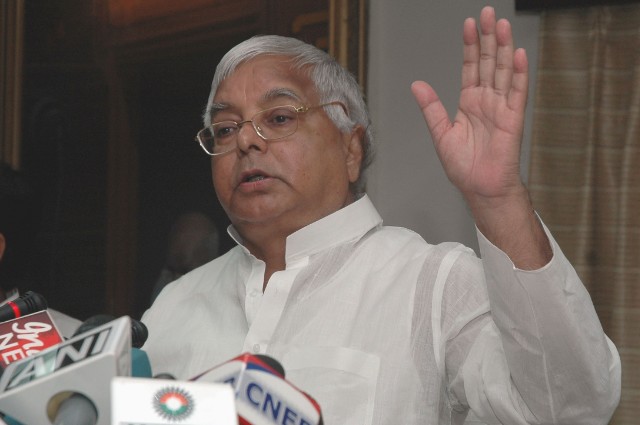

At the center of the storm was Lalu Prasad Yadav, the charismatic Chief Minister who once embodied the hopes of marginalized communities. Known for his earthy wit and grassroots appeal, Lalu had risen as a symbol of empowerment for backward classes, challenging entrenched caste hierarchies. But the scam tarnished his legacy, transforming him from a populist leader to a controversial figure synonymous with political corruption.

The Fodder Scam was more than just a financial fraud; it was a grim reflection of systemic corruption, the nexus between power and privilege, and the fragility of governance. As the case unraveled, it exposed not only the misuse of public funds but also the moral compromises that eroded public trust in institutions. This tale of deceit and betrayal continues to serve as a cautionary reminder of the perils of unchecked power.

1. Early Life of Lalu Prasad Yadav

Lalu Prasad Yadav's life story is a compelling narrative of ambition, struggle, and the sociopolitical currents that shaped Bihar's history. His early years, deeply rooted in rural India, coupled with the political awakening during his student life, laid the foundation for a remarkable yet controversial career.

Background and Upbringing

1. Birth and Family:

- Born on June 11, 1948, in Phulwaria village in Bihar’s Gopalganj district, Lalu Prasad Yadav hailed from the Ahir Yadav community, traditionally associated with dairy farming. His upbringing was shaped by the hardships of rural life and the systemic discrimination faced by his caste.

- His family’s modest means meant that luxuries were scarce, yet they managed to provide for his education, an opportunity not afforded to many in his community at the time.

2. Caste Discrimination and Early Struggles:

- Lalu grew up witnessing stark caste-based inequalities, with the upper-caste landlords exercising dominance over marginalized communities. This reality deeply influenced his perspective and fueled his determination to rise above societal constraints.

- Villagers mocked his ambition, nicknaming him “barrister” for his clean clothes and dreams of breaking free from caste oppression. Ironically, this ridicule became a motivator for young Lalu.

3. Childhood Resilience:

- Even as a child, Lalu displayed leadership traits. He often stood up for his peers and took pride in challenging the norms that oppressed his community. This early defiance would later become a hallmark of his political career.

Education and Entry into Politics

Lalu’s educational journey, though not academically distinguished, was pivotal in shaping his political consciousness.

1. Relocation to Patna:

- In 1954, Lalu moved to Patna under the care of his maternal uncle, Yadunandan Rai, who worked as a milk supplier to Patna Veterinary College. This shift marked the beginning of his exposure to urban life and broader societal dynamics.

- He enrolled at Miller High School, where he completed his basic education. While his grades were modest, his charisma and natural leadership began to shine through.

2. College Years at Patna University:

- In 1966, Lalu joined Bihar National College (affiliated with Patna University) to study political science. The college, known for its vibrant political culture, introduced him to the ideological debates and student activism that would define his career.

- Lalu’s ability to connect with fellow students, particularly those from rural and backward-class backgrounds, earned him widespread popularity.

3. First Steps in Politics:

- In 1967, he was elected General Secretary of the Patna University Students’ Union (PUSU), signaling the beginning of his political journey. His straightforward speech and relatable demeanor resonated with the student body, especially those who felt marginalized.

- His tenure as General Secretary laid the groundwork for greater ambitions, and in 1970, Lalu successfully contested for the presidency of PUSU. His victory symbolized the rise of a leader who could mobilize diverse groups under a common cause.

4. The Socialist Connection:

- During his student years, Lalu became associated with the Socialist Party, which focused on empowering lower castes and challenging the status quo. This alliance introduced him to prominent socialist leaders, strengthening his ideological foundation.

Influence of the JP Movement

The socio-political unrest of the 1970s and the rise of Jayaprakash Narayan’s movement against corruption and authoritarianism were turning points in Lalu’s political journey.

1. Joining the JP Movement:

- Inspired by Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), Lalu became a key participant in the movement against the Congress government’s alleged corruption and authoritarian practices. JP’s call for Total Revolution found an eager advocate in Lalu, who rallied students across Bihar.

- His ability to mobilize large crowds and unite fragmented groups earned him recognition as a rising leader in Bihar’s political landscape.

2. Emergency and Imprisonment:

- When Indira Gandhi declared Emergency in 1975, curtailing civil liberties and suppressing dissent, Lalu actively protested. His involvement in organizing anti-Emergency demonstrations led to his arrest under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA).

- Imprisonment, far from hindering his progress, enhanced his reputation as a fearless leader committed to democratic values. It also allowed him to build connections with other prominent political figures who were similarly jailed.

3. Post-Emergency Political Rise:

- After the Emergency ended in 1977, Lalu contested the Lok Sabha elections as a candidate of the Janata Party, which united anti-Congress factions. His victory marked his entry into national politics and set the stage for his future dominance in Bihar.

- His charisma, combined with his ability to speak the language of the common people, made him a formidable leader who represented the aspirations of the rural and backward classes.

Key Themes in Lalu’s Early Life

1. Empathy for the Marginalized:

Having faced caste-based discrimination firsthand, Lalu developed a deep sense of empathy for marginalized communities. This connection formed the bedrock of his political appeal.

2. Grassroots Leadership:

Lalu’s ability to engage with ordinary people and champion their concerns made him a relatable and trusted leader.

3. Anti-Establishment Ideology:

Influenced by socialist principles and JP’s movement, Lalu’s politics focused on challenging entrenched hierarchies and advocating for social justice.

Lalu Prasad Yadav’s early life is a testament to the resilience and ambition of a young boy who dared to dream beyond the confines of his rural upbringing. His journey through caste struggles, student leadership, and the JP Movement shaped him into a political leader who became synonymous with Bihar’s political identity. These formative years not only explain his rise to power but also provide insights into the controversies and challenges that defined his later career.

2. Political Ascent and Governance

Lalu Prasad Yadav's political ascent is a story of astute political maneuvering, shrewd alliances, and an impeccable understanding of the socio-political dynamics of Bihar. His rise from humble beginnings to becoming the Chief Minister of Bihar and a national political figure is a testament to his ability to harness the power of caste-based politics and tailor his leadership to the aspirations of marginalized communities. Lalu’s journey is marked by his deep-rooted connection to the backward classes, his strategic embrace of identity politics, and his leadership within the Janata Party and later, the Janata Dal. His political rise was also shaped by his ability to navigate Bihar’s fractured caste dynamics and forge a path to power by tapping into the discontent of marginalized sections.

Early Political Career

1. Election as Member of Parliament (MP) in 1977 under the Janata Party:

- Lalu’s entry into national politics came in the wake of the Emergency (1975-77), a period marked by political turmoil and widespread repression under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s rule. The Emergency was a critical moment in Indian politics, as it galvanized opposition forces, including socialist leaders like Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), who called for a mass movement against authoritarianism and corruption.

- In 1977, as part of the Janata Party, a coalition formed by anti-Congress factions, Lalu contested and won a seat in the Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament) from Maharajganj in Bihar. His success was partly attributed to his grassroots connections and ability to mobilize the backward castes and the rural electorate, a trend that would become central to his future political strategy.

- This victory was significant not only because it marked Lalu's entry into national politics but also because it showcased his ability to navigate the complex political landscape of Bihar. His socialist roots, combined with his ability to galvanize lower-caste voters, positioned him as a strong leader in the emerging anti-Congress wave.

2. Subsequent Transition to State Politics and Becoming an MLA in 1980:

- After serving as a Member of Parliament for one term, Lalu decided to focus his attention on state politics, which was where he saw the most potential for building his power base. In 1980, he successfully contested and became a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from Raghunathganj in Bihar.

- This shift to state politics was an important moment in Lalu’s career, as it allowed him to gain control over local politics and consolidate his influence within Bihar’s complex caste dynamics. Lalu’s political strategy was rooted in his understanding of the deeply entrenched caste system in Bihar, and his ability to speak directly to the issues that concerned the backward castes and Dalits.

- He capitalized on the growing discontent with the dominance of upper-caste leaders, especially the Brahmins and Bhumihars, who had traditionally controlled the political landscape of Bihar. This period marked the beginning of Lalu's rise as a champion of the socially marginalized and a leader of the backward classes.

Becoming Chief Minister

1. Rise Within the Janata Dal and Election as Chief Minister of Bihar in 1990:

- Lalu’s political ascent within the state of Bihar continued when he joined the Janata Dal, a political party that emerged as a successor to the Janata Party after the latter’s decline in the early 1980s. The Janata Dal was founded as an alliance of socialist, secular, and left-leaning forces, and Lalu quickly became one of its prominent leaders in Bihar.

- His rise within the Janata Dal was also aided by the decline of the Congress Party, which had been the dominant force in Bihar’s politics for decades. The Janata Dal presented an alternative to Congress's rule, and Lalu positioned himself as the leader of the backward and marginalized communities, capitalizing on the changing political winds in the state.

- In 1990, Lalu Prasad Yadav became the Chief Minister of Bihar, succeeding Jagannath Mishra. His rise to the highest office in Bihar was not just a personal victory but also a victory for the backward castes, particularly the Yadavs and OBCs, who had long been excluded from the corridors of power in Bihar.

- Lalu's political base was not just limited to the Yadavs, but also included Dalits, Mahadalits, and Muslims, all of whom were looking for a leader who would challenge the existing power structures dominated by upper-caste elites. His ability to unite these diverse groups was central to his political success. Lalu's image as a champion of the marginalized classes resonated with a large section of the population, making him a popular figure in Bihar’s politics.

2. Policies Focused on Empowering Backward Classes and Dalits:

- As Chief Minister, Lalu Prasad Yadav implemented policies that were aimed at empowering backward classes and Dalits. He took bold steps to redistribute power from the traditionally dominant upper castes to the OBCs and Dalits through his policies and appointments.

- One of his most significant decisions was the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations in Bihar. The Mandal Commission, which had recommended reservations for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions, was a contentious issue in Indian politics. However, Lalu, through his political pragmatism, embraced these recommendations, positioning himself as the voice of the backward classes.

- Lalu’s Mandal politics earned him tremendous support from Bihar’s Yadavs, Kurmis, Koeris, and other OBC communities, who had long been deprived of political power and economic resources. By providing reservations in education and government jobs, Lalu helped create opportunities for these communities, which in turn strengthened his political base.

- In addition to caste-based reservations, Lalu focused on land reforms and the empowerment of Dalits through various welfare schemes. These policies not only helped improve the socio-economic conditions of marginalized communities but also consolidated Lalu’s political power.

The Caste Equation

1. Lalu’s Strategic Use of Caste Politics to Consolidate Power:

- Caste politics has always been central to Bihar’s political landscape, and Lalu Prasad Yadav was a master at using caste-based identity to further his political agenda.

- The Yadavs, traditionally associated with farming and rural leadership, had long been excluded from political power, especially during the rule of Brahmin and Bhumihar dominated governments. Lalu’s rise marked a significant shift in this caste hierarchy, as he used caste-based mobilization to galvanize the support of the backward and lower castes.

- His success was grounded in his ability to unite different caste groups, particularly the Yadavs, Dalits, and Muslims, who saw in Lalu a leader who represented their interests against the entrenched elite. Lalu’s political style was defined by his emphasis on caste-based solidarity and the redistribution of political power from the upper castes to the lower castes, which earned him a loyal following across rural Bihar.

- Lalu’s rise to power marked a paradigm shift in Bihar’s politics, as it directly challenged the dominance of the upper-caste Bihar Pradesh Congress Committee and Bihar’s traditional feudal structures. He crafted his message around the notion of social justice, making it a core part of his appeal to the oppressed and underprivileged classes.

2. Implementation of the Mandal Commission Recommendations:

- One of Lalu’s most significant and controversial acts as Chief Minister was his decision to implement the Mandal Commission recommendations in Bihar.

- The Mandal Commission, established in the 1980s, recommended a 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs, a proposal that was fiercely opposed by many of the dominant upper-castes. However, Lalu, who understood the political utility of caste-based reservations, made the implementation of Mandal reservations a cornerstone of his political agenda.

- By implementing these recommendations, Lalu was able to solidify his position as a leader of the backward classes and Dalits, ensuring that his political base remained intact despite the growing opposition from upper-caste groups.

- This policy led to significant political polarization in Bihar, with OBCs and Dalits overwhelmingly supporting Lalu, while upper-caste groups, particularly the Brahmins and Rajputs, turned against him. However, Lalu managed to maintain his hold on power by successfully navigating these divisions and ensuring that his base remained loyal.

3. Origins of the Fodder Scam

The Fodder Scam, which eventually became one of India’s most infamous corruption cases, was not the product of a sudden or isolated event. Instead, it was a culmination of decades of systemic flaws, administrative inefficiencies, and entrenched corruption within Bihar’s governance framework. At the heart of this scam was the Animal Husbandry Department (AHD), a department tasked with supporting livestock welfare—a critical pillar of the agrarian economy. The scam’s origins reveal a chilling interplay of bureaucratic complicity, political patronage, and a lack of accountability, which enabled the systematic embezzlement of public funds.

The Animal Husbandry Department

The department, ostensibly created to promote livestock welfare and rural prosperity, ironically became the focal point for large-scale corruption due to its structural weaknesses and unchecked power.

1. Functions and Responsibilities:

The AHD was primarily responsible for:

- Procuring fodder, medicines, and equipment for livestock.

- Administering vaccination drives and veterinary healthcare services.

- Maintaining state-owned cattle farms and supporting dairy cooperatives.

- Bihar’s rural economy was heavily dependent on livestock, which provided farmers with milk, manure, and labor. Consequently, the department received a significant share of the state budget, often amounting to ₹40–50 crore annually by the late 1980s.

2. Budget Allocation and Vulnerabilities:

- Funds were allocated directly to district-level officials, bypassing rigorous checks and balances.

- Routine audits were either perfunctory or entirely absent, and there was little to no oversight on procurement processes, allowing officers and contractors to collude with impunity.

- The department’s reliance on outdated manual record-keeping made financial manipulation remarkably easy, as forged documents could be inserted without triggering suspicion.

3. Inherent Weaknesses:

- Opaque Procedures: The procurement process was deliberately kept vague, with contracts often awarded without competitive bidding.

- Politicization of Bureaucracy: Key positions in the department were occupied by officials with strong political affiliations, ensuring that whistleblowers were silenced and inquiries were stalled.

- Decentralized Mismanagement: Each district operated as an autonomous entity, further complicating oversight and enabling localized embezzlement to flourish.

These vulnerabilities created a perfect storm for corruption, where officials could exploit loopholes with little fear of detection or retribution.

Initial Allegations

The seeds of the scam were sown long before it became a full-blown scandal in the 1990s. The irregularities within the Animal Husbandry Department were apparent to many, but systemic complicity ensured that these early warnings went unheeded.

1. CAG Reports and Early Red Flags:

The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) raised concerns about the department’s financial practices as early as the 1980s.

The CAG noted:

- Disproportionate allocation of funds to certain districts, particularly Ranchi, Dumka, and Chaibasa.

- Inflated bills and procurement costs, far exceeding market rates.

- Non-existent suppliers receiving payments for supposed deliveries.

These observations were repeatedly included in audit reports but were largely ignored by senior officials, who either failed to act or were themselves complicit in the corruption.

2. MLAs’ Warnings:

- Several Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) highlighted the department’s irregularities during assembly debates in the late 1980s.

- Some MLAs even pointed out specific instances of fraud, such as the excessive purchase of fodder and medicines that far exceeded the actual needs of the cattle population.

- However, these concerns were dismissed or buried under bureaucratic red tape, as the nexus between officials and politicians ensured the smooth continuation of embezzlement.

3. Systemic Complicity:

- The bureaucratic machinery, instead of acting as a safeguard against corruption, became a facilitator.

- Junior officers were coerced into signing off on forged documents, while senior officials either received kickbacks or deliberately overlooked discrepancies.

- Political leaders provided cover for the scam, ensuring that investigations were stalled and whistleblowers were silenced.

Modus Operandi of the Scam

The Fodder Scam was executed with remarkable precision and audacity, involving a network of fake suppliers, forged documents, and systemic collusion.

1. Creation of Fake Allotment Letters:

- The scam began with the issuance of fake allotment letters, ostensibly authorizing the purchase of fodder, medicines, and veterinary equipment.

- These letters were forged with fake signatures of senior officials, ensuring that the fraudulent transactions appeared legitimate.

2. Bogus Vendor Companies:

- The perpetrators established a network of fake vendors, which existed only on paper. These companies had no physical offices, inventory, or staff.

- Fake addresses, often abandoned properties or fabricated locations, were used for registration.

- In some cases, real individuals were coerced into lending their names for these companies in exchange for small sums.

3. Inflated Withdrawals:

The scam involved massive over-invoicing, with amounts withdrawn far exceeding actual requirements. For example:

- Fodder orders were placed for non-existent cattle populations.

- Veterinary equipment and medicines were purchased in quantities that were impossible to consume.

Payments were often made in advance to the fake vendors, with no verification of the supplies’ delivery or quality.

4. Absurd and Forged Documents:

To substantiate the fraudulent withdrawals, the perpetrators submitted blatantly forged documents.

Instances included:

- Transport bills listing scooters and motorcycles as vehicles used to deliver several tons of fodder.

- Inspection reports signed by veterinary officers for supplies that were never delivered.

- Falsified stock registers showing inventory levels that bore no relation to reality.

5. Distribution of Embezzled Funds:

The money siphoned off through this elaborate scheme was distributed among several stakeholders:

- Clerks and junior staff: Received nominal amounts for preparing fake invoices and transport bills.

- District officers: Took significant cuts for signing off on fake allotment letters and forged records.

- Politicians: Pocketed large sums in exchange for providing political cover and ensuring that inquiries were stalled.

4. The Scam Unravels

The Fodder Scam, which had been brewing unnoticed for over a decade, began to unravel in the early 1990s. This exposure was the result of a series of investigative breakthroughs, courageous whistleblowers, and persistent journalistic efforts. Despite the scale of the scam, which involved ₹950 crore siphoned from public funds, its uncovering was almost accidental. What followed was a cascading series of revelations that implicated powerful politicians, senior bureaucrats, and a vast network of complicit individuals.

Investigative Sparks

The first cracks in the scam’s armor appeared through unrelated investigations and journalistic persistence, which slowly revealed the massive corruption within Bihar’s Animal Husbandry Department (AHD).

1. 1992: Discovery of Irregular Cash Transfers by Ranchi’s Income Tax Department:

- In 1992, officers at the Income Tax Department in Ranchi were conducting routine audits when they stumbled upon unusual cash transfers linked to employees of the AHD.

- These transactions, involving large sums of money, were flagged as suspicious due to the discrepancy between the employees’ incomes and the amounts transferred.

- Upon further scrutiny, it was discovered that these cash movements were part of fraudulent withdrawals under the guise of payments for fodder, medicines, and veterinary equipment.

- Though initially treated as an isolated case of tax evasion, the investigation soon expanded, uncovering the tip of what would become one of India’s largest corruption scandals.

2. Role of Journalist Shivanand Tiwari and Early Public Interest Litigations (PILs):

- Shivanand Tiwari, a journalist and political activist, played a pivotal role in exposing the scam to the public.

- Tiwari filed multiple Public Interest Litigations (PILs) in the Patna High Court, raising concerns about the large-scale financial irregularities within the AHD.

- His PILs, backed by investigative journalism, highlighted specific instances of fraudulent transactions, such as payments to non-existent suppliers and inflated procurement costs.

- Tiwari’s efforts brought the scam to light and pressured the judiciary to intervene, ensuring that the issue could no longer be ignored by state officials or political leaders.

3. Initial Media Reports and Growing Public Awareness:

- Local newspapers in Bihar, spearheaded by investigative journalists, began publishing detailed reports on the irregularities in the AHD.

- These reports, supported by leaked documents, revealed how the scam operated, implicating mid-level bureaucrats and district officers.

- Though dismissed initially as routine bureaucratic corruption, these reports gradually gained attention, especially as they hinted at the involvement of senior officials and political leaders.

Role of Deputy Commissioner Amit Khare

The scam’s unraveling took a decisive turn in 1996 when Amit Khare, the Deputy Commissioner of Ranchi, launched a series of bold investigations that provided concrete evidence of the scam’s scale.

1. The Raids on Animal Husbandry Department Offices:

- Acting on complaints about irregularities in fund disbursement, Khare conducted surprise raids on the AHD offices in Ranchi.

- These raids uncovered a vast network of fake bills, forged transport documents, and inflated invoices.

- Khare’s team found evidence that funds meant for fodder and veterinary supplies were being diverted into private accounts and used for personal enrichment by a nexus of officials and contractors.

- One of the most shocking discoveries was transport bills listing scooters and motorcycles as vehicles used to transport tons of fodder, underscoring the brazen nature of the scam.

2. Uncovering the Depth of Corruption:

- Thousands of documents were confiscated during the raids, revealing the systematic misappropriation of public funds across multiple districts, including Ranchi, Dumka, and Chaibasa.

- Fake allotment letters, signed inspection reports, and bogus vendor invoices pointed to the deliberate orchestration of fraud at every level of the department.

- The evidence showed that this wasn’t an isolated scam but a statewide operation, implicating senior officials and bureaucrats.

3. Amit Khare as a Whistleblower:

- Khare’s actions in exposing the scam earned him both acclaim and risk. His decision to go public with the findings brought significant national attention to the issue.

- By forwarding the evidence to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the judiciary, Khare ensured that the scam could not be brushed under the rug. His courage became a turning point in the fight against corruption in Bihar.

The CAG Report

The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) played a crucial role in providing an authoritative account of the financial irregularities in the AHD.

1. The 1993 Audit Report:

- The CAG’s audit of Bihar’s state finances uncovered that between 1988 and 1995, the AHD had fraudulently withdrawn over ₹950 crore through bogus transactions.

- The report detailed how funds were allocated to districts with inflated cattle populations, leading to fraudulent procurements and payments.

- It highlighted the lack of oversight in fund disbursement, with payments made without proper documentation or verification of goods delivered.

2. Key Findings:

- Payments to non-existent suppliers accounted for a significant portion of the scam.

- Certain districts like Ranchi, Chaibasa, and Dumka consistently received disproportionate allocations, suggesting collusion between district officers and contractors.

- Senior bureaucrats failed to address repeated warnings about the irregularities, pointing to systemic complicity.

3. Impact of the Report:

- The CAG’s findings provided undeniable proof of the scam’s scale, laying the groundwork for formal investigations by the CBI.

- The report also heightened public awareness, sparking outrage and demands for accountability.

Role of Bureaucrats and Politicians

The scam’s success was made possible by a well-organized nexus of bureaucrats, contractors, and politicians who shielded each other from scrutiny.

1. Bureaucrats as Key Orchestrators:

- Dr. SB Sinha, a senior officer in the AHD, emerged as one of the principal architects of the scam. He authorized fake allotments and ensured payments to bogus vendors.

- RK Rana, another senior official, facilitated the fraudulent transactions and acted as a key intermediary between contractors and politicians.

2. Political Patronage:

- Jagannath Mishra, a former Chief Minister of Bihar, was implicated in the scam for allegedly providing political cover to corrupt officials.

- Several legislators across party lines were found to have received bribes or used embezzled funds for election campaigns.

3. The Role of Bribes:

- Contractors and officials routinely paid bribes to politicians to ensure that investigations were stalled and whistleblowers were silenced.

- The scam exposed the deep-rooted culture of corruption in Bihar, where public funds were routinely diverted for personal and political gain.

5. Legal and Political Fallout

The unearthing of the Fodder Scam not only exposed one of the largest corruption scandals in India’s history but also initiated a series of legal and political upheavals that would dominate the state and national political landscape for years. The fallout saw the involvement of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), high-profile arrests, courtroom battles, and strategic political maneuvers to retain power. At the center of it all was Lalu Prasad Yadav, whose charisma and political acumen were tested against mounting legal challenges and public outrage.

CBI Investigation

The investigation into the Fodder Scam marked a significant shift in how corruption cases were handled in India, with the involvement of the Supreme Court and the CBI ensuring a degree of impartiality and rigor.

1. Transfer to the CBI (1996):

- The scam came under the spotlight of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in 1996, following orders from the Patna High Court and later the Supreme Court of India.

- The decision to transfer the case to the CBI was driven by the need for an independent probe, as the state machinery in Bihar, deeply intertwined with the scam, could not be trusted to conduct a fair investigation.

- The CBI’s mandate included investigating fraudulent withdrawals, identifying complicit officials and politicians, and building cases based on the seized documents and financial records uncovered during earlier raids.

2. Scale of the Investigation:

- The CBI filed 60 separate cases, implicating over 500 individuals, including senior bureaucrats, contractors, and politicians.

- Prominent among those named were Lalu Prasad Yadav, then Chief Minister of Bihar, and Jagannath Mishra, a former Chief Minister.

- The investigation uncovered systematic collusion at multiple levels, revealing how public funds were siphoned off through fake allotments, bogus invoices, and non-existent suppliers.

3. Legal and Political Implications:

- The involvement of the CBI lent credibility to the investigation but also turned the case into a politically charged issue.

- The probe became a litmus test for India’s ability to tackle high-profile corruption, with the judiciary and investigative agencies facing immense pressure from political factions.

Lalu’s Resignation and Political Maneuvers

As the CBI investigation gained momentum, the legal pressure on Lalu Prasad Yadav escalated, forcing him to take critical political steps to maintain his influence.

1. Mounting Pressure to Resign:

- In 1997, as the CBI prepared to file charges against Lalu, demands for his resignation grew louder from both the opposition and sections within his own party.

- His alleged role as a central figure in the scam made it politically untenable for him to continue as Chief Minister. However, Lalu, known for his political ingenuity, was unwilling to relinquish control of the state.

2. Formation of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD):

- Faced with dissent within the Janata Dal, Lalu broke away and formed the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) in July 1997.

- The RJD was crafted as a party representing backward castes, minorities, and marginalized groups, consolidating Lalu’s support base despite the allegations against him.

- This move allowed Lalu to retain the loyalty of his core voters, who saw him as a leader fighting against caste oppression and elite dominance.

3. Appointment of Rabri Devi as Chief Minister:

- When the pressure to resign became insurmountable, Lalu handed over the reins of power to his wife, Rabri Devi, in July 1997.

- The appointment of Rabri Devi, a politically inexperienced homemaker, was widely seen as a strategic move to retain control over the government indirectly.

- This decision was criticized as an act of nepotism but ensured that Lalu continued to wield significant influence in Bihar’s administration.

- Rabri Devi’s tenure as Chief Minister became a symbol of Lalu’s ability to outmaneuver his opponents, even in the face of legal and political adversity.

Trials and Convictions

The legal proceedings against Lalu Prasad Yadav spanned decades, marked by high-profile arrests, prolonged trials, and eventual convictions that cemented his fall from grace.

1. Lalu’s Arrest in 1997:

- In July 1997, Lalu was formally arrested by the CBI after being named as the prime accused in multiple cases related to the scam.

- His arrest was a landmark moment, as it was one of the first instances of a sitting Chief Minister being taken into custody for corruption.

- Lalu’s incarceration was met with widespread protests by his supporters, who viewed the action as a conspiracy by upper-caste elites to undermine their leader.

2. Trials in Multiple Cases:

- Over the years, Lalu faced trials in several cases related to the scam, each focusing on specific instances of fraudulent withdrawals from district treasuries like Ranchi, Chaibasa, Dumka, and Deoghar.

- The cases revealed how funds meant for cattle fodder, medicines, and equipment were systematically embezzled through forged documents and bogus suppliers.

- The trials were marked by delays, with frequent adjournments and procedural hurdles prolonging the legal process.

3. Conviction in 2013:

- In September 2013, Lalu Prasad Yadav was convicted in one of the key cases related to the scam, involving fraudulent withdrawals of ₹37.7 crore from the Chaibasa Treasury.

- He was sentenced to five years of rigorous imprisonment and fined ₹25 lakh, marking a significant milestone in the legal battle against him.

- The conviction led to his disqualification from Parliament under the provisions of the Representation of the People Act, dealing a severe blow to his political career.

4. Subsequent Convictions:

- In later years, Lalu faced convictions in additional cases, including the Deoghar Treasury case (₹89.27 lakh) and the Dumka Treasury case (₹3.13 crore), further tarnishing his reputation.

- Each conviction reinforced the narrative of Lalu as a symbol of corruption, even as his supporters continued to rally behind him, citing his contributions to social justice.

Impact on Lalu’s Legacy

The legal and political fallout of the Fodder Scam had profound implications for Lalu Prasad Yadav’s career and Bihar’s political landscape:

1. Erosion of Public Trust:

The scam and subsequent convictions severely damaged Lalu’s image as a champion of the poor, exposing him as a leader who exploited his position for personal gain.

2. Shift in Bihar’s Politics:

The revelations surrounding the scam contributed to the decline of Lalu’s political dominance, paving the way for rivals like Nitish Kumar to emerge as reformist leaders.

3. Symbol of Political Corruption:

The Fodder Scam became synonymous with the culture of corruption in Indian politics, with Lalu serving as its most visible face.

6. Sociological Implications

The Fodder Scam, while primarily a financial scandal, also has significant sociological ramifications that go beyond just the embezzlement of public funds. It reveals the interplay of caste politics, corruption, and public perception, especially in a state like Bihar, where these dynamics are deeply embedded in the fabric of governance. The scandal’s impact on Lalu Prasad Yadav’s political career is also an example of how corruption can be viewed differently based on social and political contexts. This section delves into how caste politics and the media’s portrayal influenced the perception of the scam and shaped the societal response to Lalu’s role in it.

Caste Politics and Corruption

1. The Role of Caste Dynamics in Shielding Lalu:

- One of the most significant aspects of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s political survival in the face of the Fodder Scam was his ability to leverage caste-based identity politics.

- Lalu, a leader from the backward Yadav community, ascended to political prominence by presenting himself as a champion of marginalized communities. He made caste-based empowerment central to his political agenda, particularly after he assumed power as Chief Minister of Bihar in 1990.

- By aligning with the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, which advocated for greater representation of OBCs (Other Backward Classes) in government jobs and educational institutions, Lalu consolidated the support of lower-caste and backward communities. This also included the Dalits, the most marginalized group in Bihar, who saw in Lalu a leader capable of challenging the upper-caste dominance that had historically controlled the state’s resources.

- Lalu's support base remained fiercely loyal, even as corruption charges mounted against him. For many of his followers, the Fodder Scam was seen not just as an isolated act of wrongdoing but as an extension of a corrupt system that had been in place for decades. In this sense, Lalu’s alleged corruption was viewed through a systemic lens—a product of a deeply entrenched patronage system, rather than the actions of a few corrupt individuals.

- His caste-based politics effectively shielded him from significant political fallout among his core constituents. His supporters were more focused on the benefits they received in terms of political representation, job opportunities, and affirmative action, rather than the ethical implications of his actions.

2. Corruption as a Systemic Issue Rather Than an Anomaly:

- The Fodder Scam, though an extreme example of corruption, was viewed by many as part of a broader pattern of systemic corruption that existed not only in Bihar but throughout Indian politics.

- For decades, Bihar had been governed by a system of patronage, where politicians, bureaucrats, and contractors colluded to siphon off public funds. The state’s underdeveloped infrastructure and deeply entrenched caste system created fertile ground for such practices.

- Lalu’s opponents in Bihar, especially from the upper castes, often saw him as a symbol of corruption. However, his supporters viewed his rise as part of the corruption of the system itself, rather than his personal moral failing.

- This view held that corruption was institutionalized in the political culture of Bihar, where even well-meaning leaders struggled to change the status quo. Many people saw Lalu as a product of the same corrupt system that had always existed in Bihar, believing that his ability to redistribute resources to the marginalized should outweigh his alleged wrongdoing.

3. The Role of Backward Class Mobilization:

- Lalu’s ability to mobilize the backward and lower castes—specifically the Yadavs, Dalits, and other OBCs—was critical in insulating him from the fallout of the Fodder Scam.

- These communities felt that Lalu’s leadership had been pivotal in breaking the stranglehold of the upper-caste elites on Bihar’s politics and economy. Even as corruption charges mounted, the narrative that Lalu had empowered the downtrodden communities often overshadowed the allegations of embezzlement and fraud.

- His political base, grounded in caste identity and social justice, was more focused on his role in giving them a political voice and ensuring their place in the social and economic order. For them, the Fodder Scam was an issue of less importance compared to the tangible gains they had made under his leadership.

Public Perception and Media Role

The way the media covered the Fodder Scam played a significant role in shaping public perception, both of the scandal itself and of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s political career. The way the media depicted the scam and Lalu’s involvement in it had a profound impact on the broader narrative surrounding his leadership and the integrity of the political system.

1. Media’s Coverage of the Scam:

- The Fodder Scam was exposed through a combination of investigative reporting and judicial inquiry, with the media playing a pivotal role in making it a national issue. Journalists, including Shivanand Tiwari, helped bring the scam into the public eye through articles and public interest litigations (PILs).

- Initially, the media’s portrayal of Lalu was largely positive, emphasizing his role as a champion of social justice, particularly for the backward and Dalit classes. This helped mitigate some of the early criticisms of corruption within the state. However, as the investigation into the Fodder Scam gained momentum and Lalu was implicated, the tone of the media began to shift.

- The media, particularly television news outlets and national newspapers, began to focus more heavily on the magnitude of the scam, with extensive coverage of the investigation, CBI probes, and Lalu’s subsequent trials. Reports on the scale of embezzlement, the involvement of top bureaucrats and contractors, and Lalu’s central role in the scam dominated the headlines.

- While the media’s reporting was instrumental in exposing the scam, it also led to an increasingly polarized view of Lalu. For some, he remained a hero of the backward classes, while for others, the scam epitomized the moral bankruptcy of his political leadership.

2. Polarized Public Opinion:

- The public’s view of Lalu became sharply divided along caste, political, and regional lines. Among the backward and Dalit communities, Lalu was still seen as a symbol of empowerment, a leader who had given them a voice and access to political power. For them, his contributions to caste-based welfare schemes and social justice were seen as outweighing the charges of corruption.

- For many opposition politicians, especially from the upper-castes and rival parties, Lalu’s role in the Fodder Scam tarnished his reputation irreparably. They painted him as a symbol of everything that was wrong with the political system in Bihar, associating his name with misgovernance and corruption.

- National media contributed to this narrative by focusing on the enormity of the scam and the direct involvement of the Chief Minister. Some outlets framed the story as a tragic fall of a leader who had once been a champion of the poor but had succumbed to the temptations of power and greed.

- However, Lalu’s ability to maintain a loyal voter base—despite his legal troubles—highlighted a significant cultural and political shift in Bihar. It exposed the power of caste-based politics in Bihar, where leaders who represent historically marginalized communities can often retain their influence despite scandals, especially if their actions are seen as benefiting their constituency.

7. Broader Lessons from the Fodder Scam

The Fodder Scam, while primarily a case of massive financial embezzlement, offers critical lessons in governance, judicial processes, and the deep-seated systemic issues that allow corruption to flourish. It reveals how institutional weaknesses can allow corruption to thrive at multiple levels, from bureaucrats and politicians to private contractors. Additionally, it highlights the challenges in prosecuting high-profile corruption cases and the influence of political interference on investigative efforts. The legacy of the scam has had far-reaching implications, influencing the discourse on anti-corruption reforms and the need for transparent governance.

Structural Weaknesses in Governance

1. Lack of Oversight and Accountability in Budget Allocation and Expenditure:

- One of the most significant lessons from the Fodder Scam is the lack of proper oversight in the allocation and disbursement of government funds.

- The Animal Husbandry Department’s annual budget of ₹40–50 crore was allocated without sufficient scrutiny. The funds were intended for critical services like animal healthcare and fodder procurement but were misappropriated due to the absence of rigorous financial monitoring.

- Absence of independent audits or mechanisms to verify expenditures, particularly in a high-budget department like the AHD, allowed for the creation of fake documents, bogus suppliers, and inflated procurement invoices.

- Had there been a system of random audits and checks at various stages of the expenditure cycle, the massive embezzlement may have been detected much earlier. The lack of accountability allowed those in power to exploit the system for personal gains.

2. Systemic Corruption Involving Politicians, Bureaucrats, and Private Players:

- The scam exposed the deeply embedded culture of corruption in Bihar’s political system. Bureaucrats, politicians, and contractors were complicit in the fraudulent activities, with each group benefiting from the scam in different ways.

- Bureaucrats, such as Dr. SB Sinha and RK Rana, signed off on fake bills, provided false certificates of goods received, and authorized excessive payments.

- Politicians, especially Lalu Prasad Yadav and his allies, provided political cover for the scheme, turning a blind eye to the massive misuse of public funds, as it suited their political interests.

- Contractors and vendors played a critical role by creating bogus companies, falsifying transport invoices, and inflating prices. In return, they received payments for goods that were never delivered.

- The collaboration of these three factions—politicians, bureaucrats, and contractors—formed a robust corruption network that siphoned off funds meant for public welfare. This systemic corruption was allowed to persist because of a lack of institutional mechanisms to hold these groups accountable.

Judicial and Investigative Challenges

1. Delays in Prosecution and Limitations in Judicial Processes:

- One of the major hurdles in the fight against corruption, as highlighted by the Fodder Scam, was the prolonged delays in prosecution.

- The legal proceedings dragged on for years, with frequent adjournments and procedural delays. Lalu’s supporters often claimed that the judicial system was slow in delivering justice, pointing to the lack of urgency in handling the case.

- Political interference further exacerbated the delay. Leaders with vested interests in the scandal tried to delay proceedings, making it difficult for investigators to gather irrefutable evidence. This lengthy trial process allowed many key figures in the scam to evade immediate consequences.

- Moreover, multiple cases related to the scam were filed, but these were handled separately and over an extended period, prolonging justice even further. The slow pace of prosecution undermined public confidence in the judicial system’s ability to effectively address corruption at the highest levels.

2. Impact of Political Interference on Investigations:

- Political interference was another key challenge in the investigative process. Despite the case being transferred to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which was meant to ensure an independent investigation, the political pressures from those implicated in the scam made the probe exceedingly difficult.

- Lalu Prasad Yadav’s political allies in Bihar, along with corrupt bureaucrats, attempted to stall the investigation by influencing key decision-makers and hindering the investigation’s progress.

- In some instances, the police and lower-level officers involved in the case faced threats and intimidation. The political climate at the time, especially in Bihar, was such that local law enforcement and bureaucracy were often reluctant to take strong actions against senior political figures.

- This interference resulted in inconsistent and often inadequate investigation efforts, which, coupled with delays in the legal process, allowed many of the guilty parties to evade justice or face lighter consequences.

Legacy of the Scam

1. Shaping Anti-Corruption Narratives:

- The Fodder Scam left a lasting imprint on the national anti-corruption narrative. It highlighted the vulnerabilities in the Indian political system, particularly in regions with entrenched caste-based politics and poor governance.

- Lalu Prasad Yadav’s involvement, despite his earlier image as a leader of the marginalized, showcased the hypocrisy often inherent in political leadership, where social justice rhetoric is juxtaposed with personal financial corruption.

- The exposure of such a massive scam helped raise awareness about the need for greater transparency in government dealings and the dangers of unchecked power in regions where politics is dominated by strong regional parties. It was a wake-up call for many in India about the scale of corruption embedded in the system.

2. Reforms in Public Administration:

- The scam pushed for reforms in the way public funds were managed and allocated. Though reforms took time, there was an eventual push for greater accountability in the disbursement of public funds, particularly at the district level.

- The exposure of the scam also led to calls for better auditing systems and electronic records to reduce human intervention and prevent fraud in government transactions.

- Several administrative reforms were implemented in Bihar following the scandal, although they were often criticized as being too late and inadequate. Nevertheless, the Fodder Scam acted as a catalyst for discussions about structural reforms needed to curtail corruption.

3. Electoral and Political Consequences:

- The Fodder Scam had far-reaching consequences in Bihar's political landscape. While Lalu Prasad Yadav’s ability to retain power, even after his arrest, demonstrated his political resilience, it also exposed the deep-seated corruption within his party.

- The scandal ultimately paved the way for a shift in Bihar’s political dynamics, especially with Nitish Kumar’s rise. Kumar, who initially allied with Lalu, later distanced himself and became a symbol of anti-corruption, positioning himself as a reformist leader.

- Nationally, the Fodder Scam reinforced the image of corruption associated with the Bihar government at the time, affecting not just Lalu but also other regional leaders who followed similar strategies of power consolidation.

8. The Road Ahead

The Fodder Scam was a wake-up call for India, revealing deep-rooted issues within its political, administrative, and judicial systems. Although the scandal exposed the vulnerability of governance structures, it also provides an opportunity for introspection and systemic change. To prevent similar scandals in the future, it is imperative that India undergoes comprehensive reforms in institutional practices, public engagement, and leadership accountability. The road ahead requires a multifaceted approach, focusing on strengthening financial oversight, promoting public awareness, and rebuilding the trust that has been eroded by corruption.

Institutional Reforms

1. Strengthening Financial Oversight Mechanisms and Independent Audits:

- One of the key lessons from the Fodder Scam is the lack of robust financial oversight in public administration. The Animal Husbandry Department, for instance, was able to misuse public funds for years without being detected due to the absence of independent audits and rigorous financial checks.

- To prevent future occurrences, there needs to be a comprehensive overhaul of financial monitoring systems. The introduction of real-time auditing systems and electronic record-keeping can reduce the risk of manipulation and ensure that financial transactions are transparent and traceable.

- Independent audit bodies must be strengthened to conduct thorough and timely audits, not just at the department level but across all government expenditures. These audits should be made public to ensure that both the government and the citizens have access to information about how public funds are being spent.

2. Enhancing the Autonomy and Accountability of Investigative Agencies Like the CBI:

- The Fodder Scam showed the limitations of investigating agencies, particularly the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). Although the CBI eventually took charge of the investigation, its efforts were hampered by political pressures and interference from the very powers responsible for the corruption.

- To make the CBI and other investigative agencies more effective, it is critical to enhance their autonomy. This can be achieved by insulating them from political influence through reforms in their organizational structure, such as making appointments and removals independent of political authorities.

- Accountability is equally important. The CBI’s performance should be regularly assessed by an independent body, and its findings should be shared with the public. Regular audits of the agency’s operations, as well as transparent investigation processes, can help build public confidence in its ability to function without bias.

Public Awareness and Vigilance

1. Educating Citizens on the Importance of Transparency and Their Role in Combating Corruption:

- One of the reasons the Fodder Scam persisted for so long was the lack of public awareness about the scale of corruption and the mechanisms through which it operated. Many citizens, especially in rural areas, had little knowledge of how public resources were being misused by officials.

- To build a culture of transparency, it is essential to educate the public on the importance of accountability and their role in demanding transparency. Schools, universities, and media outlets should promote civic education programs that teach citizens about their rights, the role of governance, and how they can actively participate in holding their leaders accountable.

- Civil society organizations (CSOs) and NGOs can be instrumental in spreading awareness, organizing campaigns, and creating platforms where citizens can report misuse of public funds and other forms of corruption. These organizations can also empower people to demand better governance from their elected officials.

2. Leveraging Technology to Create More Transparent Governance Systems:

- Technology offers immense potential to combat corruption and create more transparent governance systems. The Fodder Scam showed how manual record-keeping and outdated processes made it easier for officials to manipulate documents and siphon off funds.

- By digitizing government records, implementing e-governance platforms, and using blockchain technology for transactions, the government can make its processes more transparent and tamper-proof. Public access to these digital systems will enable greater scrutiny, making it difficult for corrupt activities to go unnoticed.

- Online platforms should be developed to allow citizens to track government spending in real-time, report issues, and engage in discussions on improving governance. This can also include setting up whistleblower protection systems to encourage individuals to report corrupt activities without fear of retaliation.

- Social media and open data portals could be used to highlight government inefficiencies and provide platforms for accountability, creating an informed and active public that holds leaders accountable for their actions.

Rebuilding Trust

1. Steps to Restore Public Faith in Governance:

- The Fodder Scam did not just erode public trust in Lalu Prasad Yadav but in the entire political system of Bihar, and even in India’s larger governance structures. Trust, once lost, is difficult to rebuild, but it is crucial for the functioning of a democracy.

- Consistency in accountability measures is essential. Institutions need to show that corruption will be punished through timely prosecutions, clear legal processes, and visible consequences for corrupt individuals.

- Additionally, political parties and public officials must move away from patronage politics and focus on merit-based governance, ensuring that appointments are made based on qualifications and integrity rather than caste or political allegiance.

2. Promoting Ethical Leadership and Political Reforms:

- Bihar’s history of caste-based politics played a significant role in the resilience of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s leadership, even amid charges of corruption. To prevent such situations in the future, political reforms must be enacted to encourage ethical leadership.

- Political financing needs to be reformed to make political parties more transparent about where their funds come from and how they are spent. Stronger regulations around election spending and party funding, along with stringent checks on how political campaigns are financed, can help reduce corruption at the grassroots level.

- Encouraging internal democracy within political parties would also help in ensuring that leaders are selected based on their competence and integrity, rather than their ability to navigate the system of corruption.

3. Fostering a New Political Culture:

- Leadership accountability must be prioritized at all levels of government. Leaders should be held accountable not only for their actions but also for the actions of those they appoint to positions of power.

- A culture of ethical governance should be promoted across India, particularly in states like Bihar where corruption has been a persistent issue. Political leaders must make a concerted effort to distance themselves from corrupt practices and lead by example, showing the public that ethical governance is possible.

- Youth participation in politics is also key to the future of ethical governance. Encouraging young leaders to enter politics with a focus on integrity and public service can help combat the deep-rooted culture of corruption. By creating a new generation of leaders committed to transparency, India can begin to heal the wounds inflicted by the Fodder Scam and similar scandals.