Image by Fajrul Falah from Pixabay

Introduction

In the realm of Indian politics, conflicts are a regular occurrence, often escalating into violent incidents. West Bengal, situated in the eastern part of the country and boasting a population of around 101 million individuals, has been deeply entrenched in a history of political violence spanning several decades. This tumultuous landscape has left a profound mark on the state's political framework, characterized by a cycle of violence persisting across different ruling parties since Independence. From the Indian National Congress to the Communist Party of India (Marxist)-led Left Front and presently the All India Trinamool Congress (AITC or TMC), the shift in power has not stemmed the tide of violent clashes, particularly prevalent in rural areas. As a result, the phenomenon of political violence in West Bengal has become a central theme in Indian public policy discourse.

This paper endeavors to delve into the historical underpinnings and distinctive characteristics of political violence in West Bengal, aiming to unravel why the state experiences a form of political strife distinct from that witnessed elsewhere in India. The structure of the paper is as follows: firstly, it provides a concise overview of the relationship between democratic politics and violence; secondly, it conducts a historical analysis of political violence in West Bengal under various political regimes; thirdly, it delves into the key factors driving this culture of violence; and finally, it scrutinizes the unique nature of violence in West Bengal compared to other states and its repercussions on democratic governance within the state.

Political Violence and Democracy

The correlation between democracy and violence is undeniable, as evidenced by numerous instances even in the most established democracies worldwide. From the late 1980s to the 2000s, countries across Western Europe, including Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and Germany, grappled with outbreaks of political violence stemming from both left-wing and right-wing extremist groups. More recently, global events such as the Brexit debate in the United Kingdom, the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, and the 2020 US elections have also been marred by episodes of political violence.

However, it's often observed that political violence is more prevalent in developing countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In these regions, intense and recurrent violence is frequently linked to political party rivalries, weak institutional frameworks, selective enforcement of the rule of law, and other structural factors. Violence becomes a means to secure electoral advantages, perpetuate political dominance, seize state resources, and monopolize democratic spaces, becoming disturbingly normalized in the political arena.

In theory, democracy is supposed to serve as a check against violence. Political scientist Neera Chandhoke argues that democratic societies provide avenues for individuals and groups to address grievances and advocate for change through civil society campaigns and parliamentary representation. Democracy, according to this perspective, opposes the rule of violence, aiming for collective decision-making and peaceful resolution of conflicts, as articulated by Hannah Arendt.

However, in practice, violence often intertwines with democratic politics. Political theorist John Schwarzmantel suggests that the political sphere is inherently linked to the use or threat of physical coercion to achieve political goals. The state, whether democratic or otherwise, tends to monopolize violence through legitimate means, ostensibly to maintain security but often resulting in the suppression of dissent and the perpetration of state-led violence against those challenging the existing order.

Defining political violence involves considering motives, timing, actors, and activities. Schwarzmantel defines it as the use or threat of physical coercion to bring about political change or defend the existing political order, distinguishing it from criminal violence. However, this definition may overlook systemic forms of political violence inherent in certain social and political systems, challenging not only the institutions of liberal democracies but also the processes of democratization themselves.

Locating Political Violence in the Indian Context

While extensive scholarly work exists on political violence in the developing democracies of Africa and Latin America, the same cannot be said for India. Despite a long history of election-related clashes and various forms of conflicts, much of the political scholarship in India has focused on communal riots, ethnic tensions, and insurgencies. States like Bihar, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Jharkhand, and West Bengal have witnessed notable episodes of such violence.

In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, criminal mafias control certain districts, often employed by politicians to eliminate rivals from opposing parties or even within their own ranks. Communal tensions have flared up in states like Gujarat, UP, and Maharashtra, with political motivations often underlying such incidents. Caste-based violence is prevalent in states like Rajasthan, UP, and Bihar. Additionally, India has grappled with violent ethnic, religious, and ideological insurgent movements in regions such as the north-east, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, as well as Maoist insurgency in eastern and central states.

Defining political violence in the Indian context is challenging due to the nation's diversity, where a multitude of socio-cultural, economic, and political factors intersect to fuel conflicts, often with state facilitation. Political violence in India encompasses a range of forms, from extremist and caste-based violence to communal tensions and economic offenses, all influenced by political factors. This interconnection of political violence with other forms is evident in West Bengal as well.

However, violence in West Bengal is intricately tied to the state's political history and culture, primarily used to seize and maintain political power. Unlike in other states, where socio-cultural, ideological, or economic factors play significant roles, in West Bengal, violence is predominantly wielded to exert political dominance and foster polarizing partisanship. This unique manifestation of political violence sets West Bengal apart from other states in India.

This paper aims to explore both visible and invisible forms of political violence in the West Bengal, including tactics of intimidation, manipulation of elections, and structural violence. By categorizing violence based on frequency and magnitude, it will distinguish between large-scale episodic violence, such as rioting, and smaller-scale everyday violence, such as targeted clashes and harassment in rural areas. The normalization of such everyday violence over the past five decades underscores its significance in understanding the political landscape of West Bengal.

Understanding the Scale of Violence

Accurately documenting and enumerating instances of political violence in India poses a significant challenge. Often, violent incidents go underreported by law enforcement due to reluctance in registering First Information Reports (FIRs), influenced by political pressures. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) faces limitations in data collection, contributing to discrepancies in reported numbers between ruling and opposition parties.

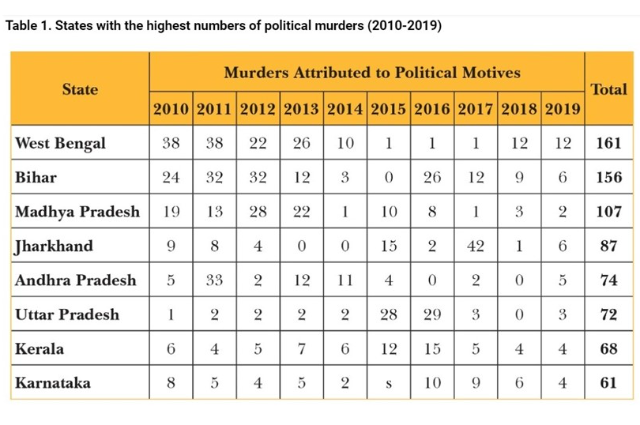

Despite these challenges, the NCRB records "murders due to political reasons," offering some insight into the scale of political violence across states. According to the latest NCRB report of 2021, West Bengal has the highest number of political murders in the country, with notable rates also observed in states like Kerala and Jharkhand. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar report the highest numbers of overall murders.

For instance, a recent report by The Times of India highlighted over 200 political murders in Kerala over the last three decades, primarily stemming from rivalry between Left parties and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

[IMAGE CREDIT: NCRB CRIME IN INDIAN REPORT 2010 to 2019: Motivesof Murder – Political]

West Bengal has long been embroiled in high levels of violence along party lines, as evidenced by NCRB data recording an average of 20 political killings annually from 1999 to 2016. The recent escalation of violence primarily involves clashes between workers of the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) and the main opposition force, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Since the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, NCRB data indicates that there have been 47 political killings involving TMC and BJP workers, with the majority occurring in South Bengal. Many analysts attribute this surge in violence to the BJP's aggressive efforts to challenge the TMC's dominance.

Even top leaders of both parties became targets of violence during the highly contested 2021 assembly elections in the state. Allegations of attacks on leaders were exchanged between the TMC and the BJP, with each party dismissing the other's claims as political maneuvering. Following the announcement of the election results, reports of renewed violence emerged, with both the TMC and the BJP blaming each other. Despite the BJP's significant gains in the state Assembly, the TMC retained power for the third consecutive term.

However, political violence in West Bengal extends beyond election periods, manifesting as everyday violence or the looming threat of violence, often with implicit support from state institutions. This pervasive violence bears a distinct political character, reflecting the broader tensions and power struggles within the state.

Political Violence of West Bengal in Brief

The roots of political violence in Bengal stretch back to its pre-Independence history, notably stemming from the nationalist movement and the tumultuous response to the Partition of Bengal in 1905 by the British. This partition sparked the emergence of a revolutionary protest movement in the early 20th century, with secret societies like Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar leading armed resistance against colonial rule. Additionally, communal tensions flared, exemplified by events like the Great Calcutta Killings of 1946 and the Tebhaga Movement of 1946-1947, a violent peasant uprising.

Following Independence, Bengal continued to grapple with political unrest, exemplified by the Naxalbari rebellion of 1967. This insurgency, led by radical communist factions, aimed to overthrow the state administration and resulted in both indiscriminate violence by insurgents and harsh repression by law enforcement authorities. These historical incidents have left a lasting legacy of political violence in Bengal, shaping its contemporary political landscape.

Congress vs. the Left: Institutionalising ‘Everyday Violence’

The ascent of the Left Front, spearheaded by the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI(M)), in the late 1960s marked a significant shift in West Bengal's political landscape, further entrenching the culture of political violence in the state. As the Left Front emerged as a formidable challenger to the long-standing dominance of the Congress party, violent clashes between their respective workers became commonplace. Notable among these incidents are the brutal Sainbari murders of Congress workers in Purba Bardhaman district on March 17, 1970, and the assassination of All India Forward Bloc Chairman Hemanta Basu in Kolkata on February 27, 1971. These events laid the groundwork for the proliferation of a 'gun culture' in the region.

Following the 1972 assembly elections, the Congress party regained power after brief interludes of opposition-led coalition governments, including those involving Left Front parties. However, allegations abound that the Congress victory was secured through coercive tactics, including the expulsion of opposition party workers from their operational areas, the establishment of a climate of fear through police and hired mercenaries, and widespread electoral malpractice. The period between 1972 and 1977 saw a relative absence of political violence in the state, characterized instead by Congress's undisputed control, which stifled political opposition and dissent.

The Emergence of CPI (M) and the Utilization of Political Violence

When the CPI (M)-led government assumed power after the Assembly elections of 1977, it largely mirrored the Congress in its approach to violence. Alongside notable reform measures in rural areas, it displayed a more organized repression of opposition forces. The government introduced significant rural reforms, particularly empowering the rural local self-governing bodies, the panchayats, and allocating substantial resources to them. This move turned the panchayats into a battleground for major political parties, with the CPI (M) using its well-structured machinery to dominate these institutions and solidify its hold over the rural electorate.

Additionally, the government launched a land reform initiative known as “Operation Barga,” which aimed to register sharecroppers officially in land records and distribute some vested lands among the landless. This measure helped bolster support for the Left government among the rural poor, who comprised a significant majority of the state's population at the time.

As economic and land resources became scarce due to rapid population growth, changing agrarian structures, and an influx of refugees, rural communities increasingly relied on government-provided goods and services. However, under the Left Front government, the delivery mechanism became increasingly controlled by the party, with preferential treatment given to villages supportive of the CPI (M). Government reform programs were often presented as party initiatives, leading to the utilization of panchayat funds to strengthen party organizations.

Political scientists noted the pervasive influence of the CPI (M) in rural Bengal, where the party became the central institution of social and political life, overshadowing traditional institutions like family, caste, and religion. This led to the coining of the term "party society" to describe the complete politicization of society in the state.

With the CPI (M) firmly in control of West Bengal politics, dissenting voices were stifled through everyday violence or threats of violence. Opposition party workers and supporters faced harassment, property damage, and even violence, while the state police often turned a blind eye to these excesses. Instances of violence, such as the Marichjhapi massacre, the murder of monks belonging to Ananda Marg, and the lynching of landless laborers, underscored the extent of political violence during Left Front rule.

The peak of political violence occurred in Nandigram village, where clashes over land acquisition led to numerous fatalities. This incident marked a turning point in the state's politics, as public sentiment turned against the Left Front, ultimately resulting in its defeat by the TMC in the 2011 Assembly polls.

Continuation of Violence in the reign of Trinamool Congress

After dislodging the three-decade-long Left Front government in 2011, the Trinamool Congress (TMC), led by Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, initially pledged to break away from the "politics of retribution" practiced by its predecessors. However, once in power, the TMC resorted to similar violent methods, targeting and killing opposition party workers. In the nine months following the 2011 Assembly polls, 56 CPI (M) members were allegedly killed in attacks carried out by TMC workers.

During the 2018 panchayat elections conducted under TMC rule, polling day witnessed widespread violence, resulting in 10 deaths. Reports from local media indicated rampant fraud, booth capturing, and burning of ballot papers, often in the presence of passive police officials. The TMC reportedly secured 34 percent of seats uncontested, purportedly due to coercion preventing opposition party candidates from filing nominations. Even after the elections, the BJP accused the TMC of continuing violence, with several of its workers allegedly killed by TMC activists.

Violence marred the Lok Sabha elections in the state the following year, with notable incidents including the vandalizing of a statue of social reformer Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar in a Kolkata college, allegedly by BJP workers, sparking clashes between the TMC and the BJP.

The 2019 Lok Sabha election results signaled a decline for the Left Front and a rise for the BJP as the main opposition party to the TMC. However, this surge in BJP support was accompanied by an escalation in political violence. In 2019 alone, there were 12 incidents of political killings involving TMC and BJP workers. In February 2021, Union Home Minister Amit Shah claimed that 130 people associated with the BJP had been killed in TMC attacks.

The Assembly elections of March-April 2021, held in eight phases, saw the TMC securing another decisive victory despite a strong challenge from the BJP. However, post-election results, violence erupted once again in the state. The BJP alleged that 14 of its party workers were killed in TMC attacks, while the TMC claimed that three of its cadres were killed by the BJP. This heightened political polarization has led to a breakdown in communication between the TMC and the BJP, with the BJP filing a criminal case against the TMC in the Calcutta High Court following the post-poll attacks.

Agrarian Conflicts in rural West Bengal

In the agrarian landscape of West Bengal, historical land relations rooted in the feudal zamindari system have bred deep-seated tensions and conflicts. From the Mughal era onwards, agrarian distress and peasant resistance have characterized the region, highlighting the enduring fault lines between landlords and impoverished peasants.

Following Independence, the Congress Party, largely supported by landlords, paid scant attention to the plight of the rural poor. The ascent of the Left in Bengal marked a significant shift, mobilizing support from the middle and lower ranks of the peasantry, particularly those from lower castes and minority communities. This partisan divide took on a class dimension, with Congress aligned with landlords and the Left gaining support from peasant communities.

When the CPI (M) assumed power in 1977, the middle peasantry, its core supporters, supplanted landlords as the ruling elite in rural Bengal. However, the landless agricultural laborers, although aligned with the CPI (M) and receiving nominal benefits, remained marginalized within the power structure.

During the 1980s, the waning influence of landlords led to a conciliatory approach towards the Left Front, resulting in their incorporation into the power structure alongside the affluent middle peasantry. Meanwhile, the plight of the landless remained dire, with only sporadic relief measures.

Towards the end of Left Front rule, disillusionment among the landless peasantry intensified, exacerbated by government land acquisition policies. Their loyalty gradually shifted towards the emerging political force, the TMC, initially perceived as a party aligned with the landed gentry like the Congress.

However, the 2019 Lok Sabha elections witnessed a significant realignment as lower-caste Hindu peasantry, particularly Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups, drifted away from the ruling TMC towards the BJP. This shift underscores the intertwining of class interests and grievances within West Bengal's agrarian economy, further fueling party-based violence in rural areas.

Panchayats: The Strategic Path to Electoral Dominance

In a democratic framework, the quest for political power often compels parties to resort to various tactics, including violence, to strengthen their grip on governance. With the increasing devolution of power and resources to panchayats during the 1980s and 1990s, these local bodies have evolved into pivotal battlegrounds for political supremacy. In West Bengal, panchayats serve as strategic platforms for parties to extend their influence across various facets of rural life.

Securing dominance at the panchayat level not only allows parties to expand their political reach but also enables them to bolster their organizational infrastructure for electoral competition. For ruling parties like the CPI (M) or the TMC, which wield significant state machinery, particularly control over law enforcement agencies, exerting influence over panchayats through coercion or the specter of violence becomes relatively easier.

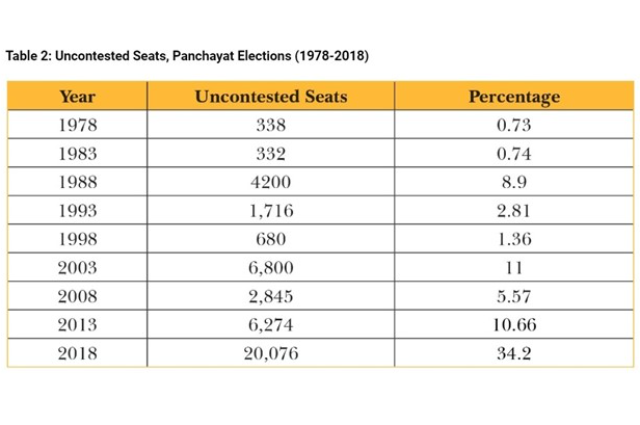

A significant indicator of this phenomenon is the number of uncontested seats in panchayat elections in West Bengal over the years, as depicted in Table 2. These uncontested seats represent areas where the ruling party effectively dissuaded opposition participation through intimidation or the fear of reprisal, thereby ensuring their own electoral victories. The surge in the proportion of uncontested seats, particularly evident in the 2018 panchayat elections where 34 percent remained unchallenged amidst widespread violence, underscores the entrenched nature of this tactic, with the TMC emerging victorious.

[IMAGE CREDIT: Times of India]

Control over Resources and Patronage

During the tenure of the Left Front, access to governmental welfare schemes was predominantly limited to families affiliated with the ruling party. These schemes, vital for the survival and livelihoods of the rural poor, served as a crucial source of social and economic security. However, control over these resources was tightly held by village-level party workers, intensifying competition and perpetuating violence in regions grappling with poverty and unemployment.

Furthermore, the practice of 'rent-seeking,' wherein ruling party activists exploit their positions for personal enrichment and to fund party activities, proliferated in rural Bengal. This rent-seeking behavior, deeply entrenched during the Left Front's rule, persisted and evolved under the TMC government. It manifests in various forms, such as the necessity of securing the blessings of local power brokers for property transactions or the compulsory procurement of construction materials through local 'syndicates.' While this phenomenon isn't unique to West Bengal, its prevalence is notably pronounced in the state, fostering a climate of competition and violence among rival factions.

The Dynamics of Fear in Political Violence

In West Bengal's deeply polarized political landscape, cadres of opposing parties view each other with apprehension and fear, perceiving rival party members as the 'other.' This apprehension stems from a belief that if a rival party assumes power, its members will inflict violence and usurp the rent-seeking benefits enjoyed by their counterparts. Often, unemployed youth are enlisted as foot soldiers by political parties to engage in attacks and intimidation against rival party workers. In this environment, rural party workers feel compelled to suppress rival factions, often resorting to violence, in order to safeguard their own security and economic interests.

Party loyalty serves as the primary fault line, exacerbating existing social divisions such as caste prejudices, class conflicts, and communal tensions. For instance, historical rivalries between the Congress and CPI (M) encapsulated class conflicts between landlords and peasants, while contemporary clashes between the TMC and the BJP incorporate Hindu-Muslim hostilities. The BJP's allegations of Muslim 'appeasement' by the TMC effectively mobilized Hindu voters in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, illustrating how communal tensions are exploited for political gain.

Moreover, the pursuit of retribution or 'revenge' plays a significant role in the politics of fear and anger in the state. Targeted killings, particularly following elections, are intended to intimidate and punish members of the defeated party. In some cases, familial disputes are expressed through the lens of political affiliation and polarization. The pervasive influence of political parties, particularly at the grassroots level in rural Bengal, underscores the significance of political dominance not only for the parties themselves but also for ordinary supporters, whose security and livelihoods are intricately tied to the dominance of their preferred party.

The BJP's Ascendancy and Escalating Violence

Following the TMC's ascension to power in 2011, its cadres adopted tactics reminiscent of the Left Front, targeting and intimidating CPI (M) workers. Despite securing a landslide victory in the 2018 panchayat elections, allegations of violence perpetrated by the TMC against opposition parties, particularly the CPI (M), fueled anti-TMC sentiment in various parts of the state. As CPI (M) supporters found themselves increasingly vulnerable and politically marginalized, many shifted their allegiance to the BJP during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, viewing it as a more viable option for challenging TMC dominance and ensuring their protection.

The BJP, bolstered by its national stature and right-wing affiliations, emerged as a formidable counterforce to TMC violence. However, this power struggle between the TMC and BJP exacerbated reciprocal violence, often taking on a communal dimension, especially during religious festivals like Ram Navami and Moharram. Despite the TMC's resounding victory in the 2021 Assembly polls, the atmosphere of fear and hostility persisted, exacerbated by post-election incidents allegedly involving TMC workers targeting their rivals.

Notably, the BJP, as the main opposition force in Bengal, has also been implicated in fomenting violence, particularly in areas where it holds significant political influence. Reports of intimidation and assault targeting TMC workers have been rampant, escalating from the 2019 Lok Sabha elections to the lead-up to the 2021 polls. This capacity for counter-violence against the TMC can be attributed to two key factors: first, many foot soldiers and prominent leaders within the state BJP are defectors from the TMC and CPI (M), well-versed in West Bengal's culture of violence. Second, as the ruling party at the national level, the BJP possesses the resources and institutional support to engage in similar tactics, as evidenced by the involvement of central forces during the Sitalkuchi firing incident in April 2021, highlighting the direct influence of Centre-controlled institutions in West Bengal's violence discourse.

The Uniqueness of Political Violence in West Bengal

The nature and dynamics of political violence in West Bengal set it apart from other states in India, embodying a distinct brand of "exceptionalism" characterized by several key factors:

- Longevity and Partisan-Driven Violence: Political violence in Bengal has persisted for over seven decades, driven primarily by partisan interests aimed at capturing and maintaining political power. This enduring trend distinguishes Bengal from other states where political violence may be more sporadic or episodic.

- Ideological Fluidity: Unlike states such as Kerala where political violence is often rooted in ideological differences between the Left and the RSS/BJP, Bengal exhibits a notable ideological fluidity. The movement of significant proportions of CPI (M) cadres to the TMC and subsequently to the BJP, as well as the migration of leaders between these parties, underscores the shifting ideological landscape of Bengal's politics.

- Primacy of Political Domination: In contrast to states like UP, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra where violence often stems from local socio-cultural prejudices and communal sentiments, political violence in West Bengal is primarily driven by the pursuit of political domination. Socio-cultural, ideological, and economic factors take a backseat to the overarching goal of political supremacy, distinguishing Bengal's violence from that seen elsewhere.

- Endemic and Everyday Nature: Political violence in Bengal has become deeply entrenched in the state's political culture, transcending the confines of election cycles to become an "everyday" occurrence. The party-society matrix facilitates this violence, with systemic exclusion and threats of violence perpetuated systematically with the complicity of state institutions and the active involvement of party organizations. This pervasive violence aligns with Johan Galtung's concept of "structural violence," imposing barriers to political participation, equality, and the rule of law.

- Exceptional Intensity and Form: The intensity and form of political violence in Bengal have no parallel elsewhere in India, exerting a significant toll on the state's economy, policies of inclusion and resource redistribution, governance systems, and rule of law.

Given these unique characteristics, addressing the issue of political violence in Bengal necessitates a comprehensive debate on the institutional safeguards, legal protections, electoral behavior changes, and shifts in political culture required to mitigate its current level and form.

. . .

References:

- Bajpai, G. S., & Kaushik, A. (2019, October 29). NCRB Report: Criminally negligent. Deccan Herald*. Retrieved from [https://www.deccanherald.com](https://www.deccanherald.com )

- Singh, V. (2021, January 9). Bengal tops in Political Murders. *The Hindu*. Retrieved from [https://www.thehindu.com/news (https://www.thehindu.com)

- "Political Violence subverts the basic ideals of democracy". (2019, May 27). *Times of India*. Retrieved from [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com](https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- NP, U. (2021, July 21). Political killings in Kerala: The violence between the Left and the Right began over 70 years ago. *Scroll.in*. Retrieved from [https://scroll.in](https://scroll.in/article)

- Kumar, R. (2020, October 5). NCRB Data Shows Bengal Recorded Highest Political Murders in 2019, Revised Figures to Show Higher Deaths. *News18*. Retrieved from [https://www.news18.com](https://www.news18.co m/news)

- Mondal, P. (2020, November 16). Decoding Political Killings in West Bengal. *New Indian Express*. Retrieved from [https://www.newindianexpress.com](https://www.newindianexpress.com)