Introduction

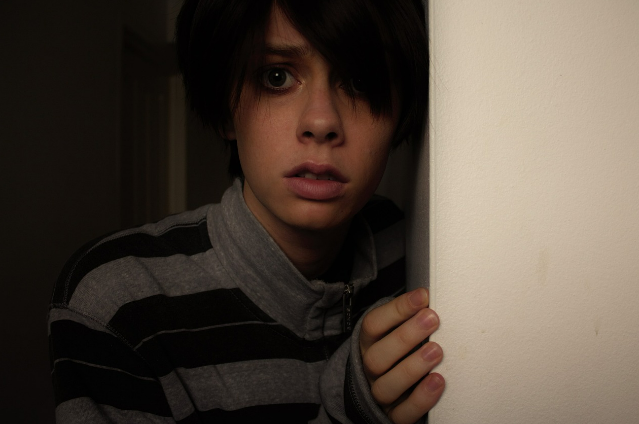

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a cognibehavioural disorder that develops due to exposure to a traumatic event, such as assault, warfare, accidents, domestic abuse or any other life-endangering situation. This disorder leads to disturbing thoughts, feelings or dreams related to the events, mental or physical distress, alterations in the way one thinks and feels and an increase in the fight-or-flight response. These symptoms last for more than a month after the event. A person with PTSD is at a higher risk of suicide and intentional self-harm.

Generally, people who have experienced a traumatic event will have reactions such as shock, anger, nervousness, fear or guilt. These reactions are common and temporary. However, for an individual with PTSD, these feelings will continue and may even increase in intensity. People with PTSD thus cannot efficiently carry out daily activities as well as they could before the trigger event.

History

Although PTSD was formally recognised as a disorder relatively recently, its symptoms have been evident for centuries. Written sources of ancient Assyria from 1300 to 600 BCE elaborate on the challenges faced by soldiers in reconciling their past actions in war with their civilian lives. This indicates the observation of what is now known as war-related PTSD.

American psychiatrist Jonathan Shay is known for finding links between textual pieces of evidence of psychological problems in history to the modern-day definition of PTSD. He is responsible for finding connections between the actions of Viking berserkers and the hyperarousal of PTSD. He also compared the experiences of Vietnam War veterans with the descriptions of war and homecoming in the influential ancient Greek author Homer's classic works, the Iliad and Odyssey. These texts, written over 2500 years ago, make numerous references to the devastating impact of the Trojan War on the survivors. The long-term psychological damage faced by soldiers was described long before the term ‘PTSD’ had been coined. Shay also suggested that Lady Percy's soliloquy in Shakespeare’s play “Henry”, written around 1597, represents an unusually accurate description of PTSD symptoms.

Before its coinage, war-related PTSD was often known as soldier's heart, shell shock, combat fatigue, gross stress reaction, war neurosis or combat neurosis. Combat-related trauma is not the only type of trauma described in the past. German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin coined the term ‘Schreckneurose’ (German for ‘fight neurosis’) in the late-nineteenth century to denote anxiety symptoms that developed after serious accidents and physical injuries. Similarly, German neurologist Hermann Oppenheim coined ‘traumatic neurosis’ in the late-nineteenth century to describe anxiety in response to extreme stress.

Following the Great London Fire of 1666, famous English diarist Samuel Pepys wrote: "It is strange to think that to this very day I cannot sleep a night without great terrors of fire". This is an indisputable indication of ‘reliving’, one of the most common symptoms of PTSD. One may thus conclude that PTSD symptoms were observed and documented long before the development of the modern concept of the disorder.

The diagnosis of gross stress reaction in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (1952) has numerous similarities to the modern definition of PTSD. GSR was defined as “a normal personality using established patterns of reaction to deal with overwhelming fear in response to conditions of great stress”. The term "post-traumatic stress disorder" came into use in the 1970s primarily due to the diagnoses of U.S. military veterans of the Vietnam War. The American Psychiatric Association officially recognised the disorder in DSM-III (1980).

Since PTSD was majorly considered a combat-related disorder, American psychosocial researchers Ann Wolbert Burgess and Lynda Lytle Holmstrom defined rape trauma syndrome (RTS) in 1975. This drew attention to the striking similarities between the experiences of soldiers returning from war and the experiences of rape victims. The definition of RTS paved the way for a more comprehensive understanding of the causes of PTSD.

Upon the formalisation of PTSD in DSM-III, personal injury lawsuits began asserting that the plaintiff was suffering from PTSD. However, judges and juries often regarded PTSD diagnostic criteria as imprecise; a view shared by legal scholars, trauma specialists, forensic psychologists and psychiatrists. This led to professional discussions in academic journals, conference debates, etc. As a result, a more clearly-defined set of diagnostic criteria for PTSD were published in DSM-IV, particularly the definition of a "traumatic event".

The DSM-IV classified PTSD under anxiety disorders, but an entirely new category of disorders was introduced under DSM-5, namely the "trauma and stressor-related disorders", in which PTSD is now classified.

Cross-Cultural Validity

Much of the information mentioned above is highly American-centric and pertains to their history, culture and society. This is because even though the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual is subordinate to the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases on paper, it remains highly dominant. Researchers notably prefer DSM-5 over ICD-10. USA’s growing influence over other countries thus leads to most information that is easily accessible being Americanised.

The cross-cultural validity of PTSD has been questioned for several years. Different sociocultural contexts have different definitions and understandings of traumatic events. An event considered traumatic in one country may not be considered traumatic elsewhere. The symptoms of PTSD also differ with respect to the culture. Although symptoms often differ based on the type of traumatic event, social contexts also play a role in determining which symptoms get expressed and which do not.

Therefore, it is evident that not only would each country have a separate social basis for determining the ambit of traumatic events and expected reactions from the patient and society, but each culture would as well. In other words, even within a single country, one may find varying social definitions of trauma, stress, etc. India is a highly pertinent example of such a country. Despite being under one flag, its 1.3 billion residents belong to numerous different communities and go through a wide range of life experiences. One’s religion, caste, family structure and even statehood are factors that determine what PTSD means to them.

One cannot refute that western-derived conceptualisations of PTSD, particularly the DSM, remain dominant. This eurocentrism is evident in both clinical and research practice. However, the cross-cultural invalidity of PTSD remains apparent. The diversity in classification, measures and treatment options for PTSD in the Indian context reflects the ongoing dilemma in measuring and identifying social understandings of PTSD worldwide. Having stated that, it seems logical to delve into the history of PTSD from the Indian point of view.

The story of PTSD’s history in ancient Indian literature begins with the great sage Valmiki’s description of PTSD-like symptoms in the epic Ramayana, written over 7000 years ago. Araṇya-Kāṇḍa (The Forest Episode), the third book of Ramayana, describes Lord Rama killing the demons accompanying Maricha (Ravana’s brother) and hitting Maricha with a blunt arrow that threw him into the sea.

Many years after that traumatic incident, Ravana asked Maricha to help him abduct Rama’s wife, Sita. Upon hearing Rama’s name, Maricha’s mouth suddenly became dry. He began to tremble and lick his lower lip with his tongue. These are clear symptoms of hyperarousal.

He also described his symptoms after Rama’s arrow hit him. He said: “Now, in every tree, I see Rama with a bow and arrow, wearing black deer skin. Lord Rama appears to me like Yama (the God of Death). Sometimes, I see thousands of Rama and I am filled with terror. When I sit in solitude, I see nothing but Rama. Sometimes I see Rama in my dreams, and I often lose consciousness. Sometimes, I think that Rama is pervading the whole universe.” This indicates symptoms of re-experiencing.

Maricha further adds: “I am unable to hear the name of things which start with the letter ‘R’. When I hear that, I begin to tremble because the letter ‘R’ reminds me of Rama. So I avoid Rath (chariot), Ratna (gems) and other things that begin with ‘R’.” This becomes a sign of avoidance symptoms. To further corroborate his PTSD, the duration of Maricha’s symptoms also surpasses the required amount of time (one month) an individual must have symptoms to be diagnosed with PTSD.

In conclusion, the history of PTSD, though only elaborated upon here from the American and Indian perspectives, has its roots in every culture’s past.

Causes

War and violence have been considered the primary causes of PTSD for decades. Veterans, active military personnel and even refugees often develop PTSD due to direct exposure to death and hardships. Dangerous occupations that expose one to violence or disasters are also at risk. These occupations include police officers, firefighters, ambulance personnel, health care professionals and even journalists, among many others.

Violence inflicted upon an individual is also a major factor leading to PTSD. These include physical or verbal abuse during childhood, domestic abuse, kidnapping, rape, or any form of physical or mental torture. The intensity of the effect further changes based on the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator, the aftermath of the violent incident, etc.

Accident survivors are also at risk of PTSD. Even if the said accident was not life-threatening, one could still perceive it as traumatic. Witnessing accidents or any form of seemingly threatening and endangering situations could also result in PTSD, even if the witness was not under threat themself.

The sudden and unexpected death of a loved one is a highly traumatic event too. Though the intensity of the disorder remains mild, slightly changing depending upon the context, it remains a cause of PTSD nonetheless. Several life-threatening illnesses may also increase the risk of PTSD. These conditions include cancers, heart attacks and strokes. Trauma that is specifically related to pregnancy leads to PTSD as well. Women who experience miscarriages are at an even higher risk.

Aside from general external factors, modern research claims that susceptibility to PTSD could be hereditary. Approximately 30% of the variance in PTSD is caused by genetics alone. For twin pairs exposed to combat in Vietnam, an identical twin with PTSD was associated with an increased risk of the co-twin having PTSD compared to non-identical twins. Research has also found that PTSD shares many genetic influences common to other psychiatric disorders, including panic/generalised anxiety disorders and substance abuse.

Diagnosis

Screening

1. Standard

- PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

- Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5)

2. For children

- Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS)

- Child Trauma Screening Questionnaire

- Young Child PTSD Checklist

- Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment

DSM-5 criteria

(required symptoms for a PTSD diagnosis)

- Re-experiencing

- Avoidance

- Negative alterations in cognition/mood

- Alterations in arousal and reactivity

ICD-11 criteria

(required symptoms for a PTSD diagnosis)

- Re-experiencing

- Avoidance

- Heightened sense of threat

ICD-11 also identifies a distinct group with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). This is a result of repeated traumatisation, causing one to have an extreme form of PTSD with no chance of escape and additional symptoms such as the loss of a coherent sense of self.

Differential diagnosis

(different disorders with similar symptoms)

- Adjustment disorder- for the distress caused by a particular event but not meeting the criteria for PTSD.

- Acute stress disorder- for symptom patterns of PTSD getting resolved within four weeks.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder- for recurrent intrusive thoughts unrelated to any traumatic event.

Difficulties in diagnosis

- The subjective nature of most of the diagnostic criteria

- Over-reporting (while seeking disability benefits, mitigating criminal sentencing, etc.)

- Under-reporting (due to stigma, pride, fear, etc.)

- Symptom overlap (with obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, etc.)

- Association with other mental disorders (such as major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, etc.)

- Cross-cultural invalidity

Effects

On the patient:

- Reliving: People with PTSD repeatedly relive the thoughts and memories of their trauma. These include flashbacks, hallucinations and nightmares. They may also feel distressed when certain things remind them of the trauma, such as the anniversary date of the event.

- Avoiding: The person may avoid people, places, thoughts or situations that remind them of the trauma. This leads to social detachment (isolation from family and friends) and a loss of interest in activities that the person once enjoyed.

- Negative cognition and physiology: The person may experience cognitive distress, including problems expressing empathy or affection, difficulty falling or staying asleep, irritability, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, overwhelming feelings of guilt and shame and even hypervigilance. The person may also suffer physical symptoms, such as increased blood pressure and heart rate, rapid breathing, muscle tension, nausea and diarrhoea.

On the family:

- Impact on spouses: As PTSD patients will be emotionally unavailable, withdrawn or quick to anger, their spouses may start to drift apart. Constantly caring for and supporting the patient will begin to take a toll on the spouse, who might develop mental health concerns themselves.

- Impact on children: The child’s age, temperament, pre-existing relationship with the parent, and the support they have, are factors determining the effect of having a parent with PTSD. The child might have to take on a caring role, witness anger or violence and often feel neglected.

- Financial pressures: Hindrance in job performance due to PTSD could lead to financial pressures on the family. This could result in the inability to provide for bare necessities, adversely affecting familial relationships and financial safety.

- Behaviour change: A PTSD patient’s family members may develop behaviours that mirror the individual (thinking that people are untrustworthy, avoiding going out due to fear of danger, etc.). They may also feel helpless if the person diagnosed with PTSD remains untreated.

Treatment

Like most other disorders, PTSD has two major treatments: psychotherapeutic (counselling) and pharmacotherapeutic (use of medicines).

Psychotherapeutic:

Following are the most common approaches within psychotherapeutic treatments:

- Prolonged Exposure Therapy

Prolonged exposure therapy (PE) generally consists of 8 to 15 weekly, 90-minute sessions. Clients will first be exposed to a traumatic memory, after which they will immediately discuss it. They are then exposed to trauma-related situations that the client fears and avoids. Breathing techniques and psychoeducation are touched on in these sessions to prevent severe anxiety attacks.

PE is theoretically grounded in emotional processing theory, which advocates emotional engagement with the memory of the trauma to implement fear-reducing changes. The American Psychological Association strongly recommends PE as a psychotherapeutic treatment for PTSD.

- Cognitive Processing Therapy

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) focuses on processing the trauma using techniques from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). It usually consists of 12 one-hour weekly sessions. During the sessions, clients write about why they think they were exposed to the traumatic event or narrate the event in explicit detail.

In CPT, the client learns about the relationship between thoughts and emotions, discusses the experience and feelings of their traumatic event and attempts to strengthen beliefs, skills and strategies to combat the trauma symptoms when they arise. The American Psychological Association strongly recommends CPT as a psychotherapeutic treatment for PTSD as well.

- Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) mostly consists of 6 to 12 weekly or biweekly sessions. Clients are asked to focus on specific distressing memories while undergoing bilateral stimulation (eye movements, tones and tapping, etc.) during treatment. The patient discusses their distress thoughts while the therapist reinforces positive cognitions to reduce emotional distress related to the traumatic event.

While EMDR is a conditionally recommended treatment for PTSD by the American Psychological Association, the Australian Psychological Society considers it the most efficient treatment method.

- Other psychotherapeutic treatments

- Narrative exposure therapy- the client creates a written account of the traumatic experiences of a patient or group of patients to recapture their self-respect and acknowledge their value.

- Brief eclectic psychotherapy- the client creates a detailed account of the primary trauma experience, explores the connected emotional reactions and learns how to move forward.

- Dialectical behavioural therapy- the client first aims to accept the reality of their lives and then learns to regulate and change behaviours.

- Emotion-focused therapy- the client gains knowledge about the effect of emotional expression and identifies the potential of emotions in creating meaningful psychological change.

- Metacognitive therapy- the client aims to control their negative repetitive thoughts.

- Mindfulness-based stress reduction- the client uses a combination of mindfulness meditation, body awareness, yoga and exploration of patterns of behaviour, thinking, feeling and action.

- Occupational therapy- the client is helped with active engagement in life tasks and taught skills that help maximise their strengths and overcome barriers.

- Stress inoculation training- the client is taught a combination of techniques, including relaxation, negative-thought suppression and real-life exposure.

Pharmacotherapeutic:

Following are the most common approaches within pharmacotherapeutic treatments:

- Antidepressants

Antidepressants help patients to cope with sleeping disorders, panic attacks, depression and anxiety attacks. Popular antidepressants include SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), SNRIs (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors) and TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, amoxapine, doxepin, etc.). These antidepressants demonstrate efficacy in large, long-term controlled trials.

- Cannabis

Cannabis (also known as marijuana or weed), if taken at managed doses for a short time, is proven effective against PTSD symptoms. Studies show that cannabis reduces activity in the amygdala (a part of the brain associated with fear) and aids in blocking traumatic memories.

- MDMA

MDMA (also known as molly or ecstasy) induces rapid onset of treatment efficacy. Three doses of MDMA with therapy over 18 weeks results in a significant reduction of PTSD symptoms and increases insight and memory. Negative memories become less painful, allowing patients to have productive therapeutic sessions without severe anxiety attacks.

- Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines (also known as benzos or blues) make people calm, relaxed and drowsy. They are recommended for short-term treatment of severe anxiety, panic or insomnia. However, they are often criticised for having adverse side effects and detrimental withdrawal symptoms.

- Other pharmacotherapeutic treatments

- Topiramate- used to modulate neurotransmitters

- Stellate ganglion block (SGB)- used to block the sympathetic nerves located around the voice-box

Case Study

Introduction:

The following case study is of ‘Tom’ (anonymous), a 23-year-old white American male. Tom received Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) for approximately one year after a traumatic event during his military service in Iraq.

Background:

Tom was the third out of four children. His father was an alcoholic and majorly absent during Tom’s childhood. His parents eventually divorced. Tom was closer to his mother and siblings.

In his adolescence, Tom witnessed his best friend committing suicide. He continued to feel guilty for not being able to prevent it. Tom’s brother died in an accident when Tom was 17 years old.

Tom dealt with these events by resorting to daily alcohol and substance abuse. He decreased substance abuse after being enlisted in the US army’s infantry.

Military:

During his service in Iraq, Tom witnessed several soldiers dying and getting injured and convoys exploding by improvised explosive devices (IEDs). However, one experience stood out; when Tom had to shoot at a car trying to enter a military-controlled area. He ended up killing a pregnant woman and her born child and witnessed the (presumable) husband and father crying in despair.

A Combat Stress Control unit sent Tom to a Forward Operating Base due to his re-experiencing and hypervigilance symptoms. He was later admitted to a large army hospital for CPT.

Treatment:

Tom was diagnosed with severe PTSD, depression and anxiety after being assessed with the PTSD checklist (PCL), Beck’s Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The therapist provided feedback about the assessment results and gave an overview of CPT. She emphasised its trauma-focused nature, the expectation of out-of-session practice and the client’s role in getting well. The following table summarises Tom’s 12 sessions of CPT:

| Session 1 | The Therapist described the symptoms of PTSD and why they had not remitted. She presented an overview of the treatment process and attempted to build rapport with Tom. |

| Session 2 | Tom and the therapist discussed the event and its meaning. The therapist helped Tom recognise his thoughts and label his emotions. |

| Session 3 | Tom had to fill an ABC (a psychological tool focusing on the activating event, belief and consequence) worksheet, which the two reviewed. |

| Session 4 | There was a deeper delve into the event and Tom’s subsequent feelings of guilt, horror, anger, etc. |

| Session 5 | An improvement in openness and awareness was visible in Tom. |

| Session 6 | Tom and the therapist discussed Tom’s belief of not deserving a family of his own since he took someone else’s. The therapist noticed cognitive changes, although an emotional change was lagging. |

| Session 7 | There was a decrease in Tom’s PCL score (from 68 to 39) and his BDI-II score (from 28 to 14). The therapist introduced the safety module. |

| Session 8 | This session marked the beginning of the trust module. |

| Session 9 | Tom and the therapist talked about the idea of fatherhood and Tom’s expected child. The therapist introduced the power/control module. |

| Session 10 | The control module changed Tom’s beliefs; Tom realised how his need to control things led to the feeling of guilt after his friend’s suicide and the army incident. The therapist began the esteem module. |

| Session 11 | Tom and the therapist identified problems in self-esteem (such as emotional reasoning). The conversation shifted to Tom’s father. The therapist began the intimacy module. |

| Session 12 | Tom was accompanied to the last session by his wife and newborn daughter. He felt happy and proud to be a father. He also felt closer to his wife. |

Tools and methods used during the CPT:

Impact statements (essays that clients produce at the onset of treatment and before the last therapy session).

ABC model (a tool to recognise irrational beliefs).

Challenging Questions Sheet (a worksheet to challenge maladaptive or problematic beliefs/stuck points).

Patterns of Problematic Thinking Sheet (a worksheet to identify automatic, habitual thoughts that cause self-defeating behaviour).

. . .

Sources:

- The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders - www.who.int

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic - www.mayoclinic.org

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment - www.webmd.com

- Handbook of Integrative Clinical Psychology, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Medicine by Roland A. Carlstedt, PhD

- Ancient Assyrian Soldiers Were Haunted by War, Too | Smart News| Smithsonian Magazine - www.smithsonianmag.com

- PTSD, the Traumatic Principle and Lawsuits - www.psychiatrictimes.com

- International Surveys on the Use of ICD-10 and Related Diagnostic Systems by Juan E. Mezzich

- The Cross-Cultural Validity of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in the Indian Context: A Systematic Search and Review - PMC - www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Anxiety disorders in ancient Indian literature - PMC - www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- PTSD and Gene Variants: New Pathways and New Thinking - PMC - www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- CPT case example: Tom, a 23-year-old Iraq War veteran - www.apa.org

- Benzodiazepines and PTSD - www.ptsd.va.gov

- The Impact of PTSD on Family Members - www.rtor.org