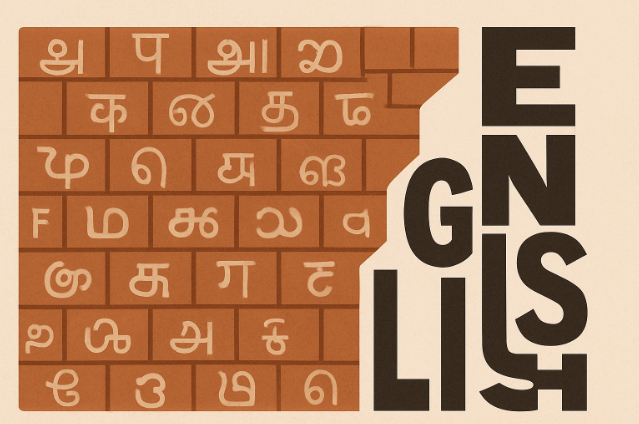

India is home to hundreds of languages. And this is not bad! This is diversity in unity — this is what makes our country beautiful. For Indians, language is not just a way of speaking; it’s a symbol of their existence, something that connects their culture, family, and emotions. Hindi is the most spoken, with 43.63% of Indians speaking it as their mother tongue, followed by Bengali at 8.03%, Marathi at 6.86%, Telugu at 6.70%, and the list continues. One of the least spoken languages is English at 0.02%. Not a big thing, you would think — but it is.

Young Indians have started using English more often to study, work, and build their careers. English is still seen as a royal language that allows them to connect globally. It is seen as a smarter, better, clearer, and more perfect language compared to their mother tongue. English is considered the first step toward growth, success, and standing out among peers. This wouldn’t have been a problem had equal importance been given to local languages. However, local languages are slowly losing credibility, being used only at home or in small groups. This raises important questions: Is the future of our country letting go of its roots? Do they no longer respect their mother tongue? Do they view it as inferior to English? In this article, we will explore how today’s India is shifting from vernacular languages to English, and how the former is struggling for survival and — if possible — revival.

English entered India thanks to the East India Company, with Lord Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education, a speech given in 1835, in which he talked about creating “a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and intellect.” However, it was only after the First War of Independence in 1857 that English was made the primary language of instruction in education, with intellectuals like Raja Ram Mohan Roy supporting it as a means to spread modern scientific knowledge. And they weren’t wrong. Its implementation, in fact, acted as a double-edged sword. On one hand, learning English enabled Indians to engage in global discourse and receive quality education. On the other hand, it created a linguistic hierarchy where English was seen as a mark of education and high status in society.

Post-independence, this language divide grew. For example, the 1956 States Reorganisation Act drew state boundaries based on the common tongue of the people in each area. This resulted in Hindi facing resistance in southern and northeastern states, where regional languages like Tamil, Telugu, and Assamese held deep historical pride, and Hindi was seen as an imposition.

In India, language is not just a mode of communication — it’s felt, performed, and inherited. From mantras in Sanskrit to bhajans in Awadhi to qawwalis in Urdu, our languages remind us of who we are. Speaking one’s mother tongue is an act of self-respect and cultural continuity. There is no harm in speaking English. Young people can and should speak English all day long if it helps them build their careers — but not at the cost of their mother tongue. Many modern young minds look at Indian languages with disdain and think that speaking them would embarrass them in front of others. They find English superior — a passport to global presence, academic prestige, and professional success.

In urban areas, among youth aged 20–24, 52% are bilingual with English as one of the languages, and 18% are trilingual — again, with English as one of the languages. In rural areas, 22% are bilingual, and 5% are trilingual. Another statistic states that 41% of wealthy Indians speak English, compared to just 2–3% among the poor. No wonder English is seen as a language of status and honour!

India has lost over 220 languages in the last 50 years, with another 197 endangered, according to the People’s Linguistic Survey of India. For example, Majhi — a language from Sikkim — has only four speakers left, all from the same family. Others include Mahali (Eastern India), Koro (Arunachal Pradesh), Sidi (Gujarat), and Dimasa (Assam). These languages are disappearing due to urban migration, lack of support, and social stigma, where speaking a native tongue is seen as backwards. And with their disappearance, centuries-old rituals, songs, history, and knowledge are vanishing. Moreover, since 1971, languages with fewer than 10,000 speakers have not been counted in the national census, leaving them excluded from policy and public attention. This linguistic erosion is not just a cultural tragedy — it’s a loss of human diversity, something that once brought pride to India.

There is some positive news, however. Movements are growing to preserve, protect, and promote endangered languages. The Scheme for Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages (SPPEL), launched in 2013, documents and archives endangered languages. Tribal languages like Bodo, Santhali, and Konkani have gained constitutional status. In many states, mother tongues are now taught compulsorily in schools, with bilingual education models helping children retain their native language while learning English as well. Apps like ShareChat, Moj, and Josh support regional languages by allowing creators to post in Bhojpuri, Tamil, Kannada, and Santali. In some villages like Mattur in Karnataka, Sanskrit is still the only language spoken by locals, keeping it alive for new generations.

Indian youth are growing up in a world where English holds international significance — often seen as the key to success in education, careers, and social standing. But languages do not die easily, especially in a country like India that has withstood the tests of time. Even as youth drift away, regional languages continue to fight for survival — often as lullabies sung by grandmothers or rituals performed on special occasions. All we can do is start respecting our mother tongue — and view English only as a language of growth, not as a symbol of our identity.