The Laws:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given to it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

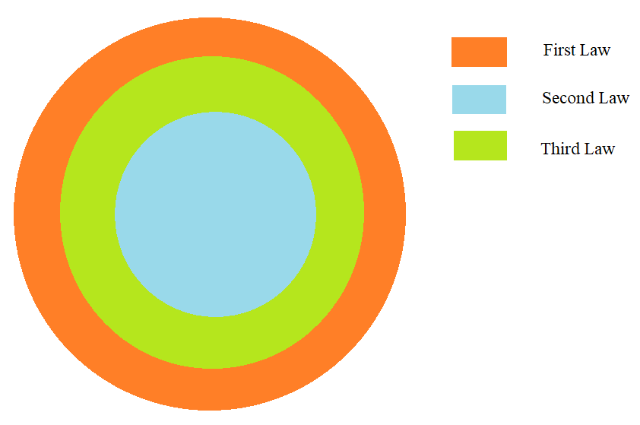

The (fictional) Three Laws of Robotics – henceforth referred to by their corresponding ordinals – were formulated by one of the giants of science fiction, Isaac Asimov, to provide a framework within which his fictional robots existed and functioned. They were a thought experiment meant to demonstrate just how obtuse the task of programming ethics into a robot can be. As the following Venn diagram illustrates, the scope of the laws is concentric: the First overrides the others, the Second only overrides the Third, while the Third is, well, not a priority.

The flipside of the First being a superset is that if it is deemed inapplicable in a case, then various nefarious implications from the Second and Third can be considered ‘(not) invalid’, because they would no longer be in contravention of the First (a crucial clause for the Laws’ consistency).

Consider ‘harm’, the explicit focus of the First and Second (and implicitly, the Third, too) – is harm to be construed only as physical harm? Even if yes, what line demarcates physical harm to a human? Does it necessarily have to be fatal – if not, then would a minor accidental cut, possibly caused by a person colliding with a robot, constitute harm? If yes, then isn’t it too narrow a definition? In contrast, if ‘harm’ were to mean mental harm, we move into similarly nebulous territory with no black and white. Finally, couldn’t harm represent harm to one’s interests, be they social, economic or political? The bottom line is, based on whatever is included or excluded from these definitions, the Second and Third could be twisted to devious ends.

Take a generic scenario – a robot X chances upon person A and B fighting, and A, about to get his jaw broken, calls upon X for help – what does X do? By protecting and defending A, it harms B, hence violating the First Law. By not protecting A, it also violates the First Law. If for a moment, we assume that A is in a position to ‘order’ (a more detailed exposition of that later) X, the latter scenario would also infringe the Second. Here, the only way X can avoid a Catch-22 is by giving some sort of precedence to either A or B, which would go against the principle of the Zeroth Law, i.e., “Humanity as a whole cannot be harmed, due to a robot’s action or inaction”. Even if we disregard the Zeroth Law momentarily, programming robots to prioritise is tricky – to bear with the earlier churlish analogy for a bit longer, what if it’s A who’s the baddie, not B? For that matter, if X were to approach this from a neutral standpoint and try to judge which human is more essential for society, it would end up in very murky waters, due to the fact that any measurement of the hazy concept of ‘utility’ is fraught with problems – too many influencing factors cannot be quantified, leaving their adjudication either to the relevant programmer’s fiat, or (more disastrously), to a utility estimate with very limited scope that only accounts for numerical metrics.

The matter of consistency is one last point of contention. The distinction between consistency in ideals and that in action is a fine one – the same action might have different justifications and different results in different scenarios. How does a robot judge when to break precedent of action, to keep in line with some ideal? By definition, exceptions and outliers can’t all be planned in advance.

All the above analysis illustrates, is that these Laws, though eminently reasonable prima facie, are actually not so – but that is to miss their point. They were never intended to be ‘actual’ laws – they only represent a framework that is created for hyper-ideal beings with (literally) ‘super-human’ capabilities to exist in a world which is far from ideal. This problem stems from a mismatch of origins. If one were to ask why humans started lying to and cheating with each-other, relativistic arguments about individual context might be raised; crucially, regardless of the conjectures, we are, as a species, a particular way, already – it cannot be altered. At the same time, with his robots, Asimov homogenises the problem of creation, albeit with the curse of knowledge, and poses a few questions – what happens if we try to create sentient creatures ourselves? Given that we are in a position to mould them as we like, would we imbibe them with some innate sense of fairness (or at least, some weak notion of non-belligerence)? Would it work?

This clashes with the fact that those creations will inhabit and exist in a world populated by teeming, nonprogrammed masses. All of the criticism that the Laws are subjected to, emanates from cases where they trip over each-other – not because they are logically inconsistent – but because they don’t adhere to certain ‘real-life scenarios’, or because the problems that are being considered are those which no one has the right answers to. In a sense, the Laws (purposefully) fail, not because robots are simple beings, but because human society and relations, with their complexity, by construction, allow for no constants, no eternally true dictums, except the most specious, specific ones – a major problem, given that while formulating generalised principles to direct robots to conduct themselves, we try to do precisely that. We forget, that if such clear principles could be formulated in the first place, we would have been following them already.

Asimov’s intent here was to spark a conversation about the true problem with ethics in robots – that of the humans at its helm. Discarding the naïve notion that it is the machine itself that is good or bad, we must understand that its decisions are influenced by the data that is fed into it. Clickbait-y articles about “racist AI” fail to acknowledge that such incidents occur due to data that has an ingrained bias against some group or the other. Thus, even sentient tech needs something to learn from, something to feed off of for knowledge – and if that river is full of muck, one can assume a reasonably similar outcome from the machine.