“A nation's culture resides in the hearts and souls of its people.” —Mahatma Gandhi

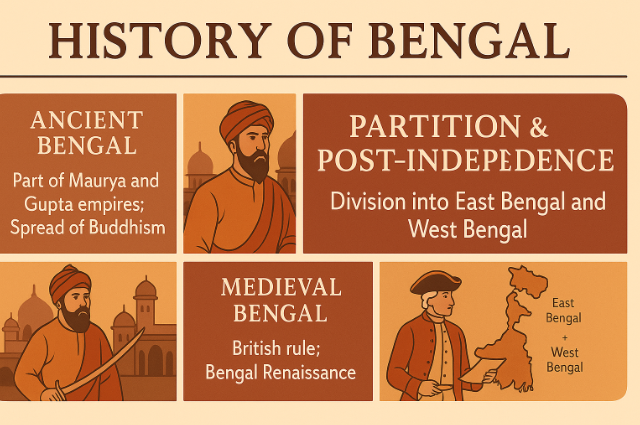

What do we know about the Bengal that is present today? Some might say today’s Bengal struggles with unemployment, political unrest, and economic decline. But! Let’s pause there, and turn back the pages of our history books – there it was, the Mughal Empire, the colonisation led by the East India Company and a major hub in that era, thriving with rich potential in trade, economy and even literature. Sounds Surprising, right? Looking at the contrast between now and then, it really looks like reading the forgotten pages of history.

Let’s delve into the Mughal era—the time when Bengal rose as a political, cultural, and economic powerhouse.

The Bengal Subah - The Rising Sun of the East

Let’s start fresh with the time after the end of the Bengal Sultanate – an independent Islamic kingdom which was the centre of Persian art, Bengal literature, Architecture and a key trade centre of the nation. This was followed by Bengal's integration into the Mughal Empire led by Akbar. The Bengal Subha was one of the largest subdivisions of the Mughal Empire, comprising present-day Bangladesh, West Bengal, and certain parts of Orissa, Bihar and Jharkhand. “Subah” in Persian means ‘Province’, where it was designed with the title, The Land Of Gold, “Sonar Bangla, praised for its immense wealth and resources.

Later in the 18th century, Murshid Quli Khan – appointed Diwan by Emperor Aurangzeb – rose into power and transformed Bengal into a virtually autonomous state. During that time, the capital was changed from ‘Dhaka’ to ‘Murshidabad’. The Bengal Subha was described as ‘The Paradise of Nation’ and as Bengal’s own ‘Golden Age’. It was one of the richest and most powerful provinces at that time. Fact check? Bengal accounted for nearly 40% of Dutch imports, making it one of the largest trade contributors in Asia. The Mughals knew that it wasn't just a province – the Money Maker, ‘the Golden Goose’, sparkling the Province. It flourished with the advancement in Textiles, muslin, silk and spices, on the verge of launching the Industrial Revolution. And Yes! It is the reason behind being the richest region in the Indian Subcontinent.

Subahdars became like mini kings – under their reign, Bengal became the buzzing hub of art, poetry, trade, and travellers. It was a true cultural blend of elegance and enterprise.

The best part? Bengal was international even back then. From Arab merchants to Portuguese missionaries, everyone had their eyes (and ships) on this power-packed province. It was that important.

The Foreign Eyes

While Bengal flourished under the Mughal Empire, the wealth of this land didn’t go unnoticed. The foreign eyes – curious, calculating and commercial – were in search of gold. European powers slowly started haunting the shores – the silk, the spices, rice, the muslin, and the cotton were the real gems.

But who came first? It was the Portuguese travellers who arrived in Bengal in 1536, establishing a trading post in Chittagong. During their ‘Age of Exploration,’ they set eyes on Bengal’s muslin, saltpetre, and textiles, also expanding their religious missions. This was indeed the first time Christianity was introduced to India, way before the Britishers. Next came the Dutch East India Company, making their trading base in Chinsurah. The Dutch mainly traded in saltpetre, muslin, indigo, and opium. Their ships carried Bengal’s treasures directly to European markets.

Then came the most powerful and influential of them all—the British East India Company, arriving in the early 1600s, setting up their powerful base in Calcutta (now Kolkata) by the late 17th century. What started as a trade slowly started turning into manipulation and politics. Bengal was too precious to be left behind. Bengal’s textiles and spices were famous in Europe. The Dhaka Muslin is a luxury.

By the early 17th century, Bengal produced more revenue than any of the other states under the Mughal Empire.

As the Europeans anchored the shores of the Ganga, Bengal was no longer merely admired, but it was soon to be wrestled away. The greed of the Europeans to purify by the water of the Ganga was the start of a devastating change in the nation. It was “The land of Paradise” quoted by the Foreigners. They were no longer visitors, but were becoming rulers.

The Terror and The Loot

This was the year 1757 – a year that would change Bengal forever.

It began with betrayal. The East India Company under Robert Clive conspired with Mir Jafar, a commander in Siraj-ud-Daulah’s army. It started the infamous battle – The Battle of Plassey in the fields of Bengal, where the British didn’t just win through bravery and strength, but through pure treachery. The Mughal Empire fell, and it was the start of the New Era, ‘British India’.

From that point on, Bengal was not the ‘Land of Gold’ but became ‘The Land of Revenue’. The British didn’t come to serve – they began to loot Bengal of all its riches. The land, which thrived with its people, now became terrorised and starved under the rule. This was the start of the biggest downfall of Bengal. The inhumane techniques – the weavers of Dhaka were forced to shut down, and lands were drained by Indigo Cultivation– Bengal was starving.

Economists like Dadabhai Naoroji would later call it the “Drain of Wealth”—where Bengal’s riches were exported to England, while her people starved. And it did happen hauntingly– The Great Famine of Bengal in 1770 killed almost 10 million people.

People were forced to produce with inadequate wages, and they became slaves in their own lands. Bengal, which was earlier called “Sonar Bangla”, was no longer thriving with resources – Fields dry, people hungry and the glory stolen.

Bengal, which earlier used to contribute almost 50% of the country’s GDP, was carried away to the foreign lands of Europe, leaving Bengal in ashes. The glory is gone and slowly forgotten.

Will Bengal rise again amidst today’s conditions?

The tragedy continues, as Bengal grapples with unemployment, economic crisis and limited resources. Once, Great Bengal turned into a slow-growing economy. It might be rightly said that greatness and wealth don’t last forever. So did Bengal. Now, we are back in the present. But the real question is: Will it rise again? Nobody really knows what their future holds. Maybe it’s not the real question whether it will rise or not – maybe it’s about remembering who we truly are and keeping the pride of ‘Sonar Bangla’ alive in our hearts.

Centuries go by, but the land never changes – it holds its legacy buried under the dust and discontent.

The real gift of Bengal’s lost glory lies in its people keeping the history alive between the pages. We carry the legacy, we walk through the soils which once rang with poetry and gold. If we listen closely, the echoes of the past aren’t lost –they are waiting.