Ashish Dhakaan, a history instructor from Gujarat, a state in western India, expressed that in our historical narrative, we have been depicted as the triumphant party in the conflict, whereas in their historical records, they assert their victory. The authors, Perrot et al., engage in a contemplation of the present condition of history education in the educational systems of India and its neighbouring country, Pakistan.

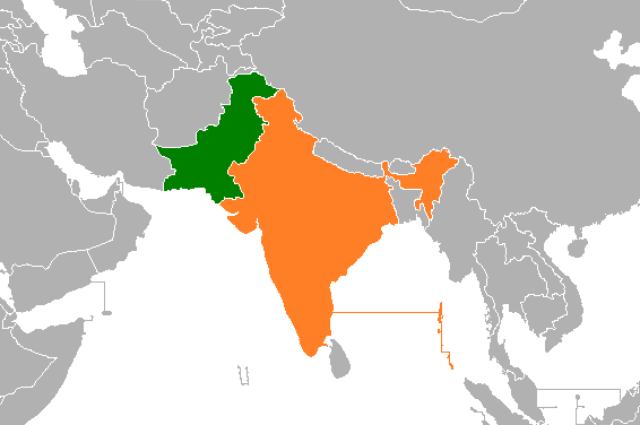

The aforementioned statements effectively draw attention to the persistent disagreement and reevaluation that surround the narratives incorporated in the history curricula of India and Pakistan. India and Pakistan, both states that emerged from the legacies of colonial authority, have made concerted efforts to build their unique identities, authenticity, and unity among their respective populations by utilising history education as a means of achieving these objectives. This matter becomes notably concerning when one considers that successive generations are prone to developing distorted and occasionally antagonistic perceptions of the other nation, despite the fact that the histories of these two countries are deeply interconnected over thousands of years of shared civilizational heritage.

Over the course of time, the pedagogy of history education for the younger cohort within educational institutions has undergone a transformation, assuming the role of a mechanism employed by governments to manipulate and reframe historical accounts in accordance with the prevailing political dynamics between states. The role of authorities has become crucial in promoting conflicting narratives among the population and shaping the perceptions of young individuals. Prominent manifestations of this tendency are seen in the educational reforms and revisionist historical narratives promoted by General Zia-ul-Haq's rule in Pakistan and the Hindu nationalist administrations in India in the late 1990s. In Pakistan, General Zia-ul-Haq placed significant emphasis on the Islamization of educational curricula, with a particular focus on incorporating Sunni Muslim beliefs. This initiative has had a lasting impact and continues to shape the educational landscape in the country. On the other hand, Hindu nationalist regimes in India have made efforts to instill Hindu nationalist ideology among the younger generation. This ideology promotes the belief that non-Hindu minorities in India, namely the Muslim community, are perceived as separate entities and are considered secondary citizens with loyalties extending beyond the borders of India. The position expressed in the statement above is in direct opposition to the historically inclusive nature of Hinduism's process of identity construction, as argued by Lall.

The Partition of 1947, a significant historical event that ended British colonial control in the Indian subcontinent and resulted in the formation of India and Pakistan as separate nations, has experienced a series of revisions and distortions over time. The advent of freedom and independence for several nations, following a prolonged period of repressive colonial rule lasting over two centuries, was met with widespread jubilation among many people. However, this significant event was overshadowed by a distressing eruption of violence. The extensive prevalence of violence resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives and the forced displacement of millions, who embarked on gruelling migrations either from India to Pakistan or vice versa, mostly motivated by sectarian connections. In their early stages as independent nations, both India and Pakistan faced significant challenges in effectively addressing and containing the widespread violence and forced migration, resulting in enduring and unresolved trauma. Following the occurrence of the tragic events, both parties assigned responsibility to one another, leading to a prolonged state of animosity and disagreement that continues to be evident in present-day discourse between the two nations.

The presence of historical tension is seen in a Pakistani intermediate-level textbook, which claims that during the partition, Muslims provided aid to non-Muslims who desired to leave Pakistan, while individuals in India engaged in acts of violence against Muslim migrants seeking sanctuary in Pakistan. The incidents encompassed acts of violence targeting buses, vehicles, and trains that were transporting Muslim refugees, resulting in instances of homicide and theft (Mazhar ul-Haq).

In contrast, one Indian textbook adopts a critical perspective by posing inquiries regarding the violence exhibited by both parties, illuminating the atrocities perpetrated by both factions under the guise of religious and nationalistic ideologies. The passage in question encourages readers to contemplate whether the partition ought to be classified solely as a structured and constitutionally sanctioned territorial division or rather as a protracted sixteen-month-long civil conflict, recognising the existence of well-coordinated factions on both sides and deliberate endeavours to eradicate entire communities (Themes in Indian istory: A Textbook in History for Class XII).

These examples illustrate that the understanding of collective historical occurrences can vary considerably based on individual viewpoints, and each country generally strives to convey its historical account in a particular way. In the context of recently formed nation-states, particularly those in the process of constructing their identities following the end of colonial governance, education plays a double function. The primary objective of this programme is to promote the intellectual growth of the younger population. Additionally, it serves as a means to widely distribute a specific interpretation of the nation's history, which is believed to enhance national cohesion and facilitate integration (Mohammad-Arif). In this particular framework, the instruction of history, together with its restructuring and narration, acquires a pivotal position.

During their periods of independence, both India and Pakistan faced the challenge of low literacy rates, limited awareness, and restricted access to information among their populations. In response, both nations recognised the potential impact of nationalised educational systems on shaping the perceptions of their citizens. Considering that the education systems in both countries are within the purview of the federal government, it is evident that both national and state governments exert significant control over the substance of the curriculum and the methods employed in teaching.

After gaining independence from colonial domination, both India and Pakistan made significant efforts to shape their national image and identity through educational initiatives. In the context of Pakistan, a significant imperative emerged to establish a harmonious alignment between the nation and its principles with the wider Muslim world, thereby establishing a distinct demarcation from India in terms of historical and cultural identity. The establishment of a distinct identity not only served to enhance Pakistan's legitimacy as a separate state within the subcontinent but also facilitated the development of a unique identity that differed from the diverse Indian identity.

This historical era presented a favourable occasion to construct a persuasive argument on the unavoidable and indisputable requirement for the establishment of an independent Muslim nation. The aforementioned statement emphasised the notion that minority communities would not get equitable rights if they continued to exist within the Hindu-majority Indian state. In contrast, India sought to establish a perception of itself as a secular and democratic nation-state that accommodated a diverse range of identities and groups. The aforementioned factor served as a distinguishing characteristic between India and Pakistan, with the former exhibiting a more secular foundation in contrast to the latter's predominantly religious one.

India and Pakistan, both countries known for their substantial ethnic, regional, and linguistic variations, have utilised history as a crucial tool to promote national unity and develop a collective sense of citizenship that surpasses these numerous, divergent, and sometimes conflicting identities (Mohammad-Arif).

The publication entitled "Partitioned Histories: The Other Side of Your Story," compiled and published by the History Project, presents a distinctive viewpoint by presenting the historical narratives taught to students in India and Pakistan in a consolidated format. This compilation elucidates the inherent biases present in the depiction of historical events, highlighting subtle nuances that may go unnoticed in the absence of the direct comparative analysis offered by this publication. Significantly, the text abstains from making evaluative statements regarding the accuracy of specific historical accounts, instead promoting the development of a sophisticated comprehension of the topic. By doing so, it provides readers with an opportunity to encounter a wide range of inequalities in the perspectives held by both parties involved.

The discrepancies between interpretations of the Mountbatten Plan, a strategy formulated by the British colonial administration to facilitate the transfer of governmental authority to India and Pakistan, serve as a notable case. The historical occurrence is treated with varied viewpoints in school textbooks throughout different nations.

The Indian perspective predominantly centres around the notion of a united India while displaying a persistent hesitation against the notion of a communal partition. The aforementioned statement highlights the importance of the collaborative decision-making process that ultimately resulted in the partition. This process was primarily led by political figures who were advocates for independence from colonial control. This narrative serves to strengthen India's pursuit of establishing a secular and democratic identity, surpassing the lingering effects of the partition. Furthermore, this phenomenon also reflects the persistent hostility expressed towards the Muslim League, which is widely seen as the primary catalyst behind the triumphant call for a sovereign Muslim nation in the Indian subcontinent.

The partition proposal for India was given by Lord Mountbatten to a council consisting of seven prominent personalities, namely Nehru, Patel, Kripalani, Jinnah, Liaqat, Nishthar, and Baldev Singh. Due to Jinnah's relentless campaigning, the leaders of the Congress grudgingly agreed to the idea, which was publicly announced on June 3, 1947. The announcement of historical significance evoked a range of feelings within the general population. Numerous Indian nationalists expressed their discontent with the partition of India, while the Muslim League maintained a degree of dissatisfaction with the precise delineation of Pakistan (Sachdeva et al.).

The portrayal of this specific historical event in Pakistani textbooks diverges significantly, placing emphasis on the pivotal contribution made by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the esteemed progenitor of Pakistan. The statement underscores the perceived favouritism towards India, underscores the sacrifices made by Pakistan in this context, and gives a perspective suggesting that Pakistan was disadvantaged in the allocation of both territory and resources.

Pakistan encountered a regrettable circumstance when Lord Mountbatten assumed the role of the final Viceroy, compelling Jinnah to acquiesce to territorial demarcations that ultimately led to the partition of Punjab and Bengal. The aforementioned boundaries were seen to have negative consequences; nonetheless, it is believed that Mountbatten employed the tactic of potentially negating the existence of Pakistan unless these limitations were accepted. Following the partition, he subsequently attributed responsibility to Quaid-i-Azam for the subsequent outbreak of violence and loss of life. Therefore, it is commonly recognised that the Mountbatten Plan entailed substantial concessions being imposed upon Pakistan. Moreover, it is widely considered that Mountbatten showed a significant inclination towards India while distributing assets, resulting in Pakistan being deprived of its rightful portion of financial resources, defence equipment, railway components, and other essential provisions (Sachdeva et al.).

The territorial dispute over Kashmir is a significant point of contention between the two nations due to its strategic significance for both parties involved. The possibility for an opponent to gain control of Kashmir is a significant concern for national security, as it might serve as a strategic entry point into the subcontinent for countries like China and Afghanistan due to its location in the Himalayan region. The portrayal of Kashmir in historical textbooks is a significant area for revision and continues to exert influence on the governments of both nations. The topic of Kashmir's independence continues to be a pertinent political matter, carrying significant real-world implications. The portrayal of the Kashmir problem in Pakistani textbooks is as follows:

Kashmir was under the governance of Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu ruler, despite the fact that the region had a largely Muslim population. Hari Singh aspired to full autonomy, declining any association with either of the two nations. In September 1947, the individual in question implemented a policy of forcefully removing Muslim Kashmiris, which subsequently prompted their resolve to respond and depose him in October 1947. In an effort to reclaim authority, the maharaja consented to the accession of India with the assurance of receiving support from the Indian government. Pakistan, in response to the military involvement, deployed its armed forces to provide assistance to the Kashmiri forces. The Indian military assumed authority over Srinagar, and following a protracted period of hostilities, India escalated the matter to the United Nations. Following the establishment of a ceasefire, the region of Kashmir was partitioned between India and Pakistan in January 1948. India was allocated a greater portion, which encompassed the capital city of Srinagar (Sachdeva et al.).

In contrast, the Indian version diverges by placing emphasis on the monarch of Kashmir's appeal for assistance in response to perceived Pakistani coercion and India's subsequent provision of aid following Kashmir's accession to the Indian Union.

Hari Singh, the sovereign of the princely state of Kashmir, initially harboured aspirations to preserve the autonomy of Kashmir. Nevertheless, he encountered provocation and coercion from Pakistan to align with their position. Tensions reached a heightened state when armed intruders, sponsored by Pakistan, initiated an invasion of the region of Kashmir in October 1947. This event ultimately led Hari Singh to sign the Instrument of Accession, aligning Kashmir with India. In accordance with the conditions of admission, the Indian Army intervened in order to safeguard Kashmir and successfully recaptured a substantial chunk of the region. However, it is worth noting that a portion of the region of Kashmir continues to be administered by Pakistan at present (Sachdeva et al., [year]).

The diverse narratives discussed in this context exhibit latent tones of antagonism, which are employed to marginalise particular communities and reinforce a carefully crafted national identity promoted by the respective administrations. The aforementioned phenomenon holds considerable ramifications for the younger cohort since they are subjected to and internalise these biases, which could conceivably shape their forthcoming responsibilities and choices. Establishing direct causal links between the education received by young individuals and the specific policy changes or diplomatic stances they adopt in adulthood may present certain challenges. However, it is apparent that even after a span of seven decades since the Partition, animosities continue to endure among subsequent generations who have not directly witnessed or experienced significant conflicts between the two nations. The persistent conflicts occurring along the borders serve to sustain these antagonistic narratives, prolonging their existence beyond mere territorial confines.

It is of utmost importance for individuals to acknowledge that historical events are rarely straightforward and that all parties involved have faced intricate and ethically demanding decisions in times of strife. However, the act of providing a critical and nuanced interpretation of history to a heterogeneous populace can potentially lead to the formation of a fragile republic, characterised by an ongoing vulnerability to internal divisions and the absence of a cohesive, unifying ideology.

The inquiry into the utilisation of history education as a means to manipulate and reconstruct historical narratives is a significant and relevant matter; however, it remains devoid of a definitive resolution. Ultimately, can a nation effectively achieve the harmonisation of its national and intellectual integrity when confronted with such decisions?

. . .

Works Cited:

- Lall, Marie. “Educate to Hate: The Use of Education in the Creation of Antagonistic National Identities in India and Pakistan.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative Education, vol. 38, no. 1, Routledge, Jan. 2008, pp. 103–19. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/03057920701467834.

- Mazhar-ul-Haq. Civics of Pakistan for Intermediate Classes: According to the Intermediate Syllabuses of All the Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education in Pakistan. Bookland and Enver-Ul-Haque Khan, 1987.

- Mohammad-Arif, Aminah. Textbooks, Nationalism and History Writing in India and Pakistan. www.academia.edu

- https://www.academia.edu. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

- PERROT, Caroline Nelly, et al. “Partition Key Battleground in India, Pakistan Textbook Wars.” AFP International Text Wire in English, Agence France-Presse, 4 Aug. 2017. ProQuest, proquest.com.

- Sachdeva, Arjun, et al. Partitioned Histories: The Other Side of Your Story. The History Project, 2016.

- Themes in Indian History: Textbook in History for Class XII. National Council of Educational Research and Training, 2017.