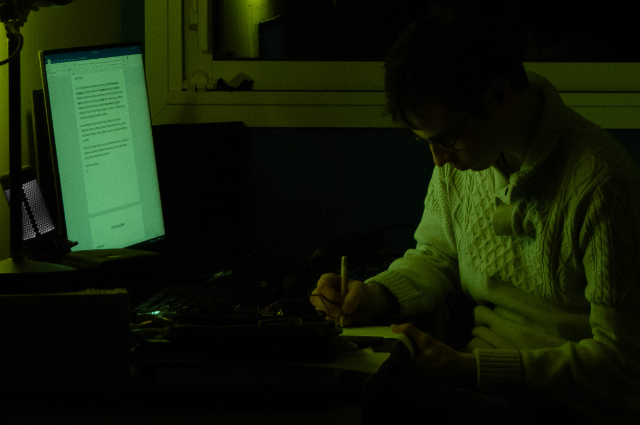

Photo by Victor Sutty on Unsplash

My friends wake up half an hour before their morning class and rush to have a small breakfast to sustain them for the next 3-4 hours. They barely have 10 minutes to finish eating. I am an oddball in this respect. I wake up at least an hour before. I do not have a lot to do in that one hour. I barely take 15 minutes to get ready for classes and maybe 5 more to head to the mess for breakfast. So, I usually reach the mess 40 min before class.

Initially, I reasoned this as me needing some time to wake up properly, get my mind going, and basically think about the day ahead. However, I realized that I want that time to linger on my ‘early morning’ thoughts as well.

The time I have before classes start, is perfect to linger around, thinking about the most random things. I do not judge what I think about and let my mind wander wherever it feels like. I do not insist on being productive in that short window. I eat my breakfast slowly, many a time thinking about the taste of that standard meal. If I meet a friend, I ask them to join me. The main feature of this small window is that it isn’t rigid/ focused. It is adaptable to my mood, mental state, feelings, and circumstances. It has a purposeful purposelessness; maybe a subtle purpose like allowing me to linger and ponder over random things that might not have been considered by me earlier. But it is definitely a fluid and adaptable space in time.

In this ‘free’ time, I look at the graffiti on the walls of the mess and wonder what it means. I notice how the mess staff changes duties daily. I know most of them by their faces. One of them always looks stoned. Another smiles at me every time I take a plate. I observe people having breakfast at the same time as me. I think about their lives and imagine what their day looks like. I sometimes see a familiar face here and there and smile at them. The mess cat, Toofan has stopped coming for breakfast. I check my phone for messages, glad for once that there mostly are none. I sometimes think about my home, my always-busy parents, and calculate the number of days I have spent away from them. Would I be able to live up to their standards? Do I want to? Having gotten too serious, I ground myself in my immediate reality again. Usually, I don’t want to start my day with intense life-threatening, and mentally exhausting thoughts. Back to people wearing some form and brand of headphones or earphones, watching something on their devices, a bubble within a larger bubble. Ashoka feels like an organism at times, buzzing with internal life, always repairing the wear and tear of its parts, and weirdly unaware of some of the elements that make it.

This lingering did not make sense to me until I read Jejuri by Arun Kolatkar. The ‘purposelessness’ is purposeful, without the pressure of having to be that. It is the same purposelessness that gives a purpose or meaning to that time. Anantha Murthy’s Venkata is a great example of a man being purposefully purposeless. The writer’s focus on such a character is in itself unconventional. Venkata isn’t much bothered by the people around him, who provoke him to do something to improve his circumstances. He is at peace in his simple life of priestly duties, massages, and casual lingering.

In Kolatkar’s Jejuri, a similar defocus can be observed. The religious elements of a place known for its temples and deities are looked at from a different angle by Kolatkar. The poet is fascinated by the place, not because of its ‘holiness’, but because of the things that are left unnoticed there. For example, a partially unhinged door, puppies in a dilapidated temple, a non-doorstep, an old beggar woman etc. His commentary on the state of Jejuri has pushed religiosity to the side and brought into the picture the usually sidelined elements. His way of defocusing and refocusing is quite unique and inspiring. It reminds me of a few of the initial stories we read wherein the colonizing Britishers were sidelined in the narratives which described the lives of some specific Indians. Tagore’s idea of the superfluous can be thought of as connecting to Kolatkar’s version of Jejuri- both talk about things not taken seriously, or even taken for granted by most. These writers subtly question the reader’s conditioning of considering certain things important and others not so much.

The private is made public up to the point where the two are inseparable. Manto’s stories also reveal the inseparability quite well- A character’s experience in the toilet is written alongside descriptions of their deep spirituality. This mix of ‘private’ and ‘public’, ‘mundane’ and ‘profound’ complicates narratives, making them more interesting. Arun Kolatkar flawlessly mixes the public and private, at times giving more importance to the private. Instead of going inside the temple to pray, he smokes outside or maybe observes a rat running around the idols. It is a collaborative space in the true sense. It involves the observer (writer, in this case) in the particular events and things of the place. The observer actively participates in creating the place for readers.

A change in vantage points creates differences between two narratives about the same place/event. Though Kolatkar writes about his visit to Jejuri, a place with religious significance, he looks at the same things differently. His attention is caught by the most mundane of things. His focus on mundanity moves quickly to a social commentary of the people of Jejuri.

The mundane is beautiful and worth writing about. It need not be a backdrop but could be the main plot. Ambai writes about the daily lives of women in the most interesting way. She chooses particular events of daily lives, conversations, actions, routines to emphasize on larger concepts of femininity, feminism, gender roles, relationships, etc. The kitchen and the food made there become the most important points in the narrative, holding the entire plot together.

My parents and I like to travel. On our trips to some of the well-known places in the country, I am excited to see the streets and get a sense of the lives of people in that particular place. I hardly remember the ‘iconic’ monuments/sites in the respective places. I have come up with some of the best ideas while lingering and engaging in aimless conversations. I have had epiphanies while ‘wasting time’.

A focused mindset, if something like this even exists, is counterproductive. A defocus is what is needed to broaden the things that are talked about. One does not hold back from having a broader perspective and the subject written about does not become stagnant. A movement away from the focus is crucial for broadening lines of thought. It brings conventionally unrelated things into conversation with each other, giving rise to an unexplored dimension.

The phrase ‘beating around the bush’ becomes vital in this context. It is mostly used in derogatory terms. But, ‘beating around the bush’ brings other things into the conversation. A defocussing takes place. It aids the churning of ideas and points of view. Diverse narratives are created. My entire essay might seem like it is beating around the bush. But I wanted it to be defocused. It reflects my usual lingering and random thoughts, heavily influenced by my perspective at that point in time.

. . .

Bibliography:

- Kolatkar, Arun, et al. Jejuri. Editions Banyan, 2020.

- Murthy, U.R. Anantha. A Horse for the Sun. 1932.

- Lakshmi, C.S. Gifts. 1945.

- Mervyn, Vikram. Nothing. Is there a Modern Indian Literature. 2023.