Imagine a startup founder stepping into a failing company—mounting losses, broken systems, demotivated people—and turning it into a profitable, self-sustaining enterprise. Now imagine this happening not in Silicon Valley, but in a drought-stricken Indian village. That is exactly what Popatrao Pawar achieved with Hiware Bazar, a small town in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar district, by applying management thinking where charity had failed.

In 1989, Hiware Bazar was on the brink of collapse. Chronic drought had depleted its groundwater, farming yields were negligible, alcoholism was widespread, and migration had become the norm rather than the exception. Families left year after year because the village could no longer sustain them. When Popatrao Pawar became sarpanch, he did not approach the role as a political position. He approached it like a CEO taking charge of a bankrupt startup.

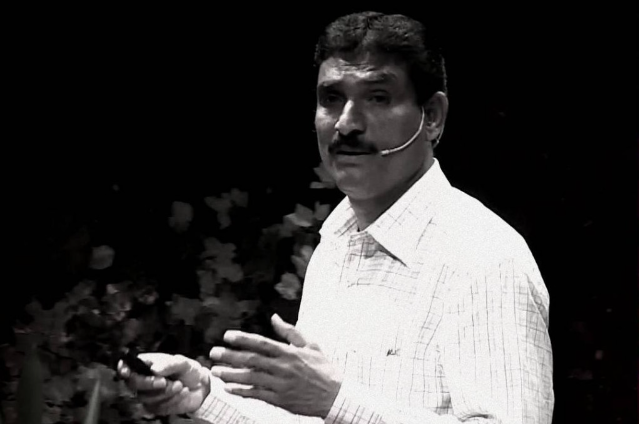

A former cricketer with a Master’s degree in Commerce, Pawar began by identifying the village’s core problem. Instead of chasing government schemes blindly, he asked a fundamental question: why was the system failing? The answer was clear—water mismanagement. Farming practices were disconnected from ecological reality. Water-intensive crops were being grown in a low-rainfall zone, borewells were drilled without limits, and there was no accountability for resource usage.

His first major intervention was what can be described as a “water audit.” Every year, the village measures its rainfall, groundwater availability, and consumption needs. This data determined how much land could be cultivated and what crops could be grown. For the first time, decisions were based on numbers rather than hope. Just like a startup aligns spending with cash flow, Hiware Bazar aligned agriculture with water availability.

Next came the pivot. Pawar banned water-guzzling crops such as sugarcane and restricted borewells entirely. These were emotionally and economically difficult decisions, but necessary. Instead, farmers were encouraged to shift to crops that were drought-resilient, high-value, and sustainable. Horticulture, vegetables, pulses, and dairy became the new economic backbone. Livelihoods diversified, reducing dependency on a single risky source of income.

But systems alone don’t scale without culture. Pawar understood that discipline was non-negotiable. The village adopted strict social rules that mirrored corporate governance. Alcohol was banned completely. Open grazing was stopped to protect plantations. Tree cutting was regulated. Participation in village decisions became mandatory, not optional. This collective discipline ensured that individual actions did not sabotage long-term goals.

What made this transformation unique was that it wasn’t enforced through force, but through consensus. Pawar invested heavily in trust-building. Decisions were discussed openly in gram sabhas. Villagers were made stakeholders in outcomes. Over time, accountability became internal rather than imposed.

The results were extraordinary. Groundwater levels rose steadily as check dams, contour trenches, and watershed structures replenished aquifers. Wells that had once run dry began yielding water year-round. Agriculture became predictable instead of speculative. Migration reversed as families returned, seeing real economic opportunity at home.

Income levels surged. From barely subsistence earnings in the early 1990s, Hiware Bazar evolved into a village where dozens of families became financially secure, some even earning at levels comparable to urban professionals. Dairy farming flourished, agricultural productivity increased, and savings replaced debt. The village moved from survival mode to growth mode.

Equally important were the social indicators. Alcoholism declined sharply. Education levels improved. Health outcomes stabilized. The village demonstrated that economic reform and social reform are not separate—they reinforce each other.

Hiware Bazar’s success drew national and international attention. Development experts, policymakers, and students began studying it as a model of sustainable rural development. Pawar was eventually awarded the Padma Shri, one of India’s highest civilian honors, for his contribution to water conservation and rural transformation.

Today, Popatrao Pawar works to replicate this model across Maharashtra through the Model Village Programme. His message remains consistent and uncomfortable: rural India does not fail due to lack of funds, but due to lack of planning, discipline, and accountability. Charity may provide relief, but management creates resilience.

The story of Hiware Bazar challenges a deep assumption—that villages need saving. Pawar proved they need leadership, data, and systems. By treating a village like a startup, he demonstrated that sustainable development is not about grand promises, but about executing fundamentals relentlessly, year after year.

In an era obsessed with innovation, Hiware Bazar reminds us that the most radical idea can be applying common sense with uncommon commitment.

. . .

References:

- Popatrao Baguji Pawar – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org

- Hiware Bazar – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org

- NDTV: Sarpanch Who Transformed His Drought-Prone Village Wins Padma Shri https://www.ndtv.com

- Reflections. Live – Inspiring Story of Hiware Bazar https://reflections.live

- Dr. Vidya Hattangadi – Self-Sufficient Indian Villages https://drvidyahattangadi.com

- Lokmat – Hiware Bazar’s Water Budgeting Practice https://www.lokmat.com