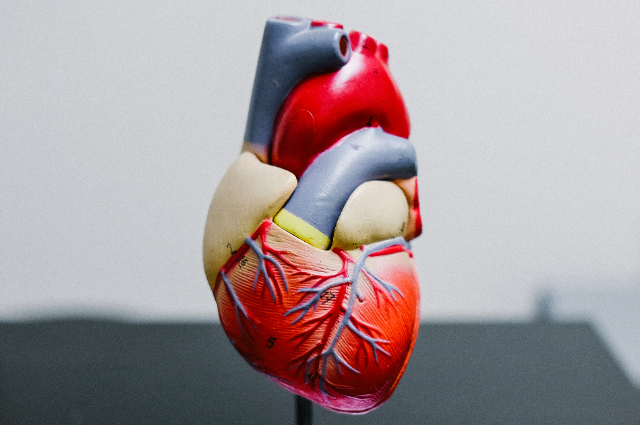

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Introduction

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) is a rare yet increasingly recognized cause of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), especially in young and otherwise healthy individuals, predominantly women. Unlike atherosclerotic heart disease, SCAD occurs when a tear forms in the coronary artery wall, leading to separation of the arterial layers and formation of a false lumen. This can block blood flow to the heart, resulting in myocardial ischemia or even infarction. Understanding SCAD is critical because its presentation, diagnosis, and management differ significantly from traditional heart attacks caused by plaque buildup.

Epidemiology

SCAD accounts for approximately 1–4% of all acute coronary syndromes, but among young women under 50 with ACS, it may be responsible for up to 35% of cases. It is also an important cause of myocardial infarction (MI) during pregnancy and the postpartum period. While historically underdiagnosed, improvements in imaging techniques and increased clinical awareness have brought SCAD into the spotlight.

Pathophysiology

SCAD involves a spontaneous tear or bleed within the coronary artery wall. This leads to the creation of an intramural hematoma or false lumen, which compresses the true lumen—the central blood-flow channel. There are two primary mechanisms proposed:

- Intimal tear hypothesis: A tear in the innermost layer (intima) allows blood to enter and dissect the wall.

- Medial hemorrhage hypothesis: Bleeding within the vessel wall, possibly from the vasa vasorum (small vessels that supply the arteries), causes separation of the arterial layers without a visible intimal tear.

The result is reduced or blocked blood flow to the heart, leading to ischemia or infarction.

Risk Factors and Associations

SCAD often occurs in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as high cholesterol or smoking. Common associations include:

- Fibromuscular Dysplasia (FMD): A non-inflammatory vascular disease that weakens arterial walls, found in 60–80% of SCAD patients.

- Hormonal changes: Pregnancy, postpartum status, or use of hormonal therapy.

- Emotional or physical stress: Intense stress, including extreme exercise or emotional trauma, has been linked to SCAD episodes.

- Connective tissue disorders: Such as Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan syndrome.

- Systemic inflammatory diseases: Like lupus or polyarteritis nodosa.

Notably, many SCAD cases occur in people without any apparent predisposing condition.

Clinical Presentation

SCAD mimics other forms of acute coronary syndrome and may present as:

- Chest pain (most common symptom)

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

- Nausea

- Syncope (fainting)

- Sudden cardiac arrest (in severe cases)

Due to its nonspecific symptoms and occurrence in younger, healthy individuals, it is often misdiagnosed initially.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of SCAD requires a high index of suspicion. The gold standard imaging modality is coronary angiography, which may reveal:

- A radiolucent Intimal flap

- A long, smooth narrowing without atherosclerotic plaque

- Contrast staining within the arterial wall

Advanced imaging like intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT) can provide more detailed visualization and confirm the presence of a dissection or hematoma.

Types of SCAD (Saw Classification)

- Type 1: Classic appearance with contrast dye entering the false lumen—easily identifiable.

- Type 2: Long, smooth narrowing due to intramural hematoma without clear dissection flap.

- Type 3: Focal, atherosclerosis-like narrowing; difficult to distinguish without IVUS or OCT.

Management

Unlike traditional myocardial infarction, SCAD is usually treated conservatively:

- Medical therapy: Includes beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, and lifestyle modification. Aspirin is commonly used; clopidogrel is debated.

- Avoidance of thrombolytics: These can worsen the dissection by increasing bleeding within the arterial wall.

- Revascularization (PCI or CABG): Reserved for patients with ongoing ischemia, large myocardial territory at risk, or hemodynamic instability. PCI in SCAD carries a higher risk of complications due to the friable nature of the artery.

Prognosis and Recurrence

Prognosis is generally favorable with proper management. Most dissections heal spontaneously over time. However, SCAD can recur in about 10–20% of cases, sometimes in different arteries. Lifelong follow-up, risk reduction, and counseling are important.

Psychosocial Impact

SCAD has a profound emotional and psychological toll, especially given its sudden and traumatic onset. Many patients develop anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Cardiac rehabilitation programs that include mental health support can improve outcomes.

Conclusion

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection is a distinctive, non-atherosclerotic cause of myocardial infarction with unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Increased awareness among healthcare providers is critical for timely diagnosis and effective management. While SCAD may initially seem alarming, with appropriate care and follow-up, most patients recover well and lead healthy lives. Further research is needed to unravel its complex pathogenesis and to develop targeted therapies and preventive strategies.

. . .

Acknowledgement: I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to GSRM Memorial College of Pharmacy, Lucknow, for fostering an environment of academic curiosity and excellence. My sincere thanks go to all the faculty members, especially those who have guided and encouraged me in my exploration of cardiovascular and pharmaceutical sciences. Your mentorship, support, and dedication have been instrumental in shaping my understanding of complex medical conditions like Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD). This work stands as a reflection of the knowledge and inspiration I have received under your guidance.

References:

- Hayes SN, et al. (2018). Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 137(19), e523–e557. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564

- Saw J, et al. (2014). Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Clinical outcomes and risk of recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol, 64(22), 2358–2365. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.026

- Tweet MS, et al. (2012). Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Recurrent SCAD and its association with fibromuscular dysplasia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv, 5(5), 543–549. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.967943

- Macaya F, et al. (2021). Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: contemporary aspects of diagnosis and patient management. Open Heart, 8(1), e001419. DOI: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001419

Authors: I am Aayush Raj Dubey. I pursued a bachelor’s degree in Pharmacy from G.S.R.M Memorial College of Pharmacy 720 Mohan Road, Bhadoi – 226008 affiliated with Dr. A.P.J Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow. I am interested in the field of Medicinal Chemistry which combines aspects of chemistry, biology, and pharmacology to design, develop, and optimize new pharmaceutical compounds for therapeutic use.