The dragon is the most expansive and enduring figure of human myth. From fire-spewing, bird-like European legends to serpent-like, water-dwelling, heavenly East Asian gods, there have been manifestations of the dragon in the mythologies of sea-divided lands and millennia. This compelling likeness poses an interesting question: why did these different civilizations, unaware of one another, all independently imagine this very same beast? Its origin is likely not in popular imagination, but in popular reality.

The dragon myth, whatever its incarnation, might well be a deep cultural memory, a collective fiction from the very factual skeletons of our Earth's prehistoric past and man's primal fears of nature.

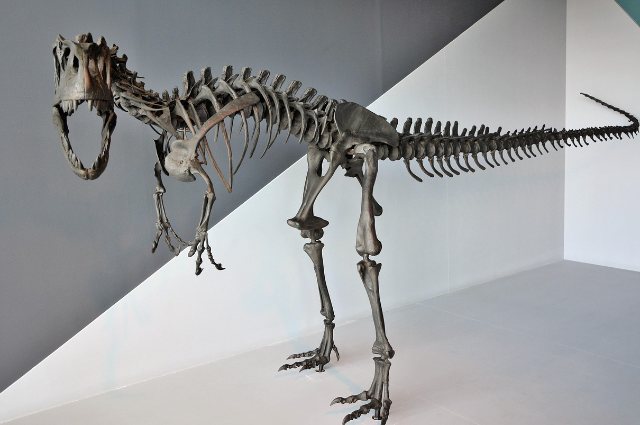

The fossil record holds the most biologically suggestive whisper for the evolution of the dragon. Men have ridden across the big, puzzled remains of giant monsters that have been dead for millennia throughout the entire world. Imagine an ancient Chinese plowman turns a field and finds the giant, sweeping skull and master backbone of a dinosaur like the Yangchuanosaurus.

No knowledge of evolution or deep time would be necessary for the only reasonable conclusion to be that this beast, in some incarnation, still exists, or just went extinct. The huge size of the bones would point towards a creature of unfathomable power. The toothed bones would point towards a carnivore. These fossilized bones provided the literal skeleton to the dragon. The cultures would set these "dragon bones" in temples or bazaars, and a myth would accumulate about them, filling out the beast once they did have them.

This explains the worldwide explanation of the legend; where there were weathered out of the earth big fossils, there were people to discover them and try to explain how they had gotten there, usually sketching out roughly the same reptile-like monster. Apart from giant bones, the dragon also represents a composite animal, a chimera of the most frightful aspects of nature.

Our ancestors did not have to see a dinosaur so that they could fear gigantic monsters. The components of the dragon are a composite of animals' parts that represent actual and potential dangers. The snake shape is an adaptation of the ancient and largely mindless fear of the snakes found on every continent except Antarctica. Their silent creep, deadly fang, and power to materialize bodily in the room of a moment seemingly made them the source of awe and terror. Scales of the dragon are crocodile or large lizard scales—armor-plated, invulnerable, and wonder-struck-appearing. Claws and talons are the attributes of a gigantic bird of prey, like an eagle or hawk, which can swoop down and grab cattle (or children).

In mythology, some dragons have bull horns or stag horns, symbolizing virility, masculinity, and uncooked strength. By combining the most lethal attributes of several predators in the shape of a singular super-predator, the myth builds the ultimate icon of nature's horror. The symbolic association of the dragon with treasure amassing has its basis in biological facts as well.

European dragons are best represented lounging on top of a mound of gold within a cave. This can be accounted for in terms of the natural inclinations of real-life animals. Some ants collect things that are shiny. But more primal even than identification with big predators that take shelter within caves, i.e., bears or big cats, lies it. A tunnel of bone-lined substance for what they consumed, even a human skull sporting a bronze decoration or helmet, can easily be confused by a panicked bystander with a pack of fiendish beasts. The bones, which are worn smooth and perhaps even partially mineralized, may sparkle like jewels or gold in the faint light of a torch. The myth of a monster guarding treasure reminds us to keep greedy grown-ups and snoop-squinting kids at bay from the killing dens of quite actual, if less mythical. Beasts. The foreboding might of spewing fire is decidedly the dragons' most unrealistic-looking characteristic, but even this has scientific reasons.

No animal ever quite succeeded in generating actual flame, but some animals have evolved the capacity that would have been called magic by a reader of a fossil record. Take the bombardier beetle, for example, that repels predators by expelling a hot chemical spray from the bottom of its abdomen with a snap.

On an even greater scale, the myth can be based on the extent and deadly danger of fires. A bolt of lightning that ignites a forest or combustible bog can appear to be a fiery breath sweeping across the earth. Filling in for this is the ubiquity of caves and dragons. Caves have small reservoirs of flammable gases like methane. If an animal were to incite one such pocket and a spark result from stones crashing into one another, a flash blast or jet of fire could burst out of the mouth of a cave, neatly ending the story of a fire-breathing monster. Even the form of the dragon is modified to fit the specific environment and phobias of a society.

In the Middle Eastern and North African deserts of water deficiency, the dragons assumed forms as gigantic snakes, representing the chaos of aridity and the auspicious yet dangerous possibility of rivers of evacuations that could overwhelm. Tiamat was a Mesopotamian goddess of the sea and an ancient saltwater monster representing chaos.

In East Asian rain-swamped and rain-fed cultures, the dragon evolved as a water god, lord of rains, floods, and typhoons.

In Chinese culture, the Long is a snake-like, wingless, wise, powerful, and auspicious creature far removed from the money-conscious, violent European dragon. This variation instructs us that the same fundamental concept—a giant, reptilian, ferocious beast—was adapted to reflect the most powerful and volatile forces of a region's landscape: drought and anarchy in the first case, wet and deadly water in the second. Finally, we must consider the extremely routine, reflexive quality of the human mind.

Humans are pattern-making animals. We are designed to see faces in the clouds and meaning in the leaves in the bushes—a quirk that served us well when faced with predators. That condition, or pareidolia, and the fear of predators are likely what went into effect. The leaves in the tall grass may be a tiger or a dragon. The gigantic unknown form at the bottom of the deep water may be a water serpent, or a log of wood. The forms produced by the shadows cast under the dim light of a cave can be like a rolled-up monster under the dim light of the fire. The dragon is the final "what if?", the brain's heuristic for staggering toward the worst, which can be inferred from partial evidence, a survival mode antidote that throws caution away.

Finally, the dragon is not a myth.

It is a cultural artifact, a palimpsest object made out of real bones, real beasts, real environmental phobias, and the primitive hardware of the human brain. It is a narrative that aided our forebears in describing a menacing and incomprehensible world. It gave shape to the fear of the black forest, the strength of a hurricane, and the enigma of giant bones on Earth.

Dragon is a work of human imagination capacity, but it finds its roots deep in the ground, rock, and biology of the very concrete world we have ever lived in.