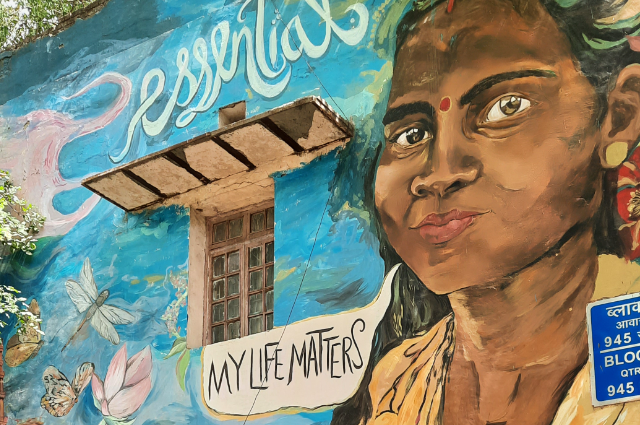

The picture shows Graffiti of the love story of veteran singer Deepali Barthakur and Artiste Nilpawan Baruah/Source: g.co/kgs

Abstract: In the modern urban milieu, graffiti and street art have ascended as profound agents of communication, manifesting both as instruments of mass discourse and platforms for individual artistic declaration. These visual narratives, imbued with symbolism, are cultural artifacts, each culture contributing a distinctive brushstroke to this global canvas. In India, where walls have historically been employed for advertisements and self-expression, Delhi has become a receptive crucible for the integration of graffiti and street art into its sociocultural fabric. This inquiry centers on comprehending the ideological underpinnings and cultural diplomacy intrinsic to graffiti in Delhi, elucidating the genesis of street art as a significant socio-political force.

Introduction:

Art has long played a significant role in shaping cities, with historical artworks serving as visible expressions of urban life. The connection between art and the city was manifested through civic monuments and religious structures. Artistic contributions were funded by the city and its residents, with monuments acting as vehicles for conveying political, economic, and social values. This paradigm, known as civic aesthetics, encompassed the holistic use of traditional visual arts alongside design disciplines in urban planning. The city's identity was intertwined with beauty, transforming streets and squares into vibrant living spaces. However, during the industrial revolution, the relationship between art, architecture, and the city underwent a shift. Architects and engineers took over urban design, relegating art to decorative functions. This separation was driven by the divergence in material innovation and changing attitudes toward public spaces. The arts evolved into autonomous disciplines, detached from urban planning. In the mid-20th century, artists rejected academic traditions, embracing art's freedom from symbolic needs. Over the last two decades, art has reemerged in urban regeneration efforts, fostering a dialogue between art, daily life, and urban spaces. This renewed focus on artistic intervention aims to enhance citizens' quality of life and their relationship with the urban environment. Art once again occupies a central role in shaping the city, as artists are called upon to imbue "spaces" with a sense of "place."

The resurgence of a holistic approach to urban design stems from the crisis of traditional rationalist planning and evolving citizen-city dynamics. Outdated models and the reliance on technical language clashed with the need to engage with residents' daily lives. Contemporary European cities seek a blend of art and urban planning to address their complex challenges, from physical transformations to cultural diversity. Public art, often beyond mere decoration or commemoration, endeavors to shape policies closer to people's concerns. Such a remarkable change in the design culture fostered the birth of a heterogeneous panorama of artistic interventions in the public space, to which we commonly refer to as public art (Miles, 1997; Cartiere, Willis, 2008; Knight, 2008).

Urban regeneration, driven by culture, attracts investment and visitors. Yet, debates persist, with proponents highlighting art's positive impact on communities and skeptics noting its role in gentrification.

Recent developments in public art aim to shape a city's physical landscape while rejuvenating the fundamental fabric of urban life. This shift towards a more social dimension in art compels all stakeholders - artists, local authorities, public art agencies, and civil society - to reassess their roles and actively participate in decision-making. This participatory approach is termed "new genre public art" (Lacy, 1995).

In this context, artists collaborate with communities, address existing social issues, and engage in dialogues with residents using various modes of communication. "New genre public art" centers on the relationship between artists and their audience, defining itself as a process rather than a product (Hein, 2006). Such projects involve intricate negotiations with multiple parties, including property owners, government agencies, and environmental organizations (Hein, 2006: 75).

The evolving role of art challenges the conventional position of artists. Present-day public artists, inclined towards inquiry rather than assertion, seek to invigorate public discourse, provoking critical examination. Furthermore, artistic interventions, born from proactive collaboration between designers and residents, foster public engagement. In doing so, they revive the original essence of art as "res publica" – an entity capable of interpretation, service, and the enrichment of a defined and circumscribed community. A striking illustration of this ethos can be found in the Nuovi Committenti program, an initiative spearheaded by the Adriano Olivetti Foundation in Turin, dedicated to creating art installations within the public realm. The program outlines practices of artistic production as a possible factor of social change and promotes citizen participation in the patronage and production of contemporary art projects that acknowledge a concrete demand and are conceived as installations in the everyday living and working environment of the same patrons (Bertolino, Comisso, Parola, Perlo, 2008).

Delving into the intricate realm of public art, this researcher embarks on a modest exploration of the dichotomy between the renowned Lodhi Art District in Delhi and the lesser-recognized public art of their native Assam.

The global backdrop:

Amidst the daily hustle and bustle of urban life, there exists a profound necessity—a facet that humanizes the contemporary urban landscape stirs emotions among strangers, provides respite, and momentarily liberates us from the constraints of reality. The term 'carnivalesque,' as coined by theorist and philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, encapsulates this amalgamation of delight, artistry, and existence. In a parallel vein, street art engages with urban spaces, bestowing a refuge from the rigidity of city life and infusing an air of whimsicality into the mundane. Street art, in its multifaceted essence, encompasses interactive installations designed to further captivate the observer's imagination. It frequently amalgamates diverse mediums, ranging from graffiti to sculpture and murals, weaving a vibrant tapestry within our urban landscapes.

The surge in popularity of this democratized art form of street art and graffiti has breathed new life into many modest neighborhoods. From the vibrant streets of Shoreditch in London to the colorful corners of Wynwood in Miami, these communities have undergone remarkable metamorphoses through the medium of art.

The history of graffiti is a testament to its evolution from primitive cave drawings to a contentious contemporary art form. Its origins trace back to ancient civilizations like the Romans and Greeks, who etched their names and protests onto buildings. However, modern graffiti, as we recognize it today, emerged in the early 1960s in Philadelphia, later spreading to New York City by the late '60s. It flourished in the 1970s when individuals began tagging their names on city structures, culminating in subway cars being covered in elaborate spray-painted "masterpieces" by the mid-'70s.

Initially associated with street gangs, graffiti creators, or "taggers," formed crews to mark their territories. While some began to view graffiti as an art form, it also attracted the ire of authorities. The debate over whether graffiti is art or vandalism persists. Some, like New York City Councilor Peter Vallone, believe that graffiti can be art with permission but a crime on someone else's property. Others, like Felix of Reclaim Your City, argue that it represents freedom and rejuvenates urban spaces.

Graffiti has catapulted a select few to international fame, like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Blek le Rat, and Banksy, whose works often convey political or humorous messages and command substantial prices. Today, graffiti has transformed into a potential big business, embodying the complex intersection of artistic expression, property rights, and urban culture.

In Siberian cities, street art undertakes the ambitious task of reshaping the social, political, and axio-semiotic fabric of urban spaces. Serving as visual texts, it proves its existence and influence in Russia's eastern regions. Street art in Siberia serves diverse roles, from individual expression to addressing concealed societal concerns. It operates as a symbolic language, fostering communication and offering a platform for promoting values and ideologies. Cities such as Tomsk, Novosibirsk, Kemerovo, Novokuznetsk, Irkutsk, and Gorno-Altaisk serve as noteworthy examples of citizens' aspirations for egalitarian transformations. These include promoting art accessibility, enhancing urban aesthetics, engaging in political dialogue, and forging unique identities rooted in their places of residence.

In Italy, the historical influence of art on city development waned during the industrial era. Post-World War II, the 2% for art law aimed to rejuvenate cities through public artworks but struggled with enforcement and elitism critiques. Italy's public art regulations remain ambiguous, leading to grassroots initiatives driven by residents, artists, and private entities like Nuovi Committee, bypassing institutional channels. Now with this citation, it holds a concealed but pivotal aspect of our research, hinting at a crucial topic that will become evident as we progress further. It acts as a subtle beacon, guiding our attention towards an important subject matter yet to be fully explored within this paper.

To the mainland:

The practice of painting in public and communal spaces holds a rich history in India, with its origins tracing back to ancient times. The most ancient evidence of this tradition can be found in the breathtaking Buddhist cave paintings of Ajanta, nestled in Maharashtra. These cave murals, which date back to the second century BC and were serendipitously discovered in 1819, remain a significant chapter in the tapestry of Indian art history. Over generations, these Ajanta murals have continued to inspire artists and sculptors, firmly embedding themselves in the annals of Indian artistic heritage.

Beyond the grandeur of Ajanta, India's streets and communal spaces have also long been marked by cultural expressions. From hand-painted Bollywood posters to typographic signboards, vibrant truck art, religious imagery adorning sidewalks, and advertisements by small businesses, these public canvases narrate the diverse stories of the country. One noteworthy example is the political graffiti that flourished in West Bengal during 1960-1990, serving as a subversive outlet for social and political dissent.

However, the landscape of Indian street art has undergone transformations. As political graffiti receded in Kolkata, a new generation of artists emerged in cities like Delhi and Mumbai, such as Yantra, Zine, and Daku. Street art festivals, including those organized by the St+art India Foundation and other local initiatives, began proliferating across the nation.

The evolution of Indian street art became particularly pronounced after 2012 when social media catapulted it into the mainstream. Nevertheless, a subtle shift occurred as artists began collaborating with government bodies to create sanctioned murals. While this brought new opportunities, it also introduced constraints, potentially diluting the raw and provocative nature of street art.

The gradual transition from graffiti to street art is evident, with artists like Daku, who is commonly referred to as the Indian Banksy, moving towards more sanctioned forms of expression. This shift has raised debates about the subversive spirit being tamed in favor of a less offensive genre. Nonetheless, street art in India remains a dynamic force, evolving and shaping the visual fabric of the nation's public spaces.

Delhi, the eminent diplomatic capital of India, stands as a testament to the convergence of diverse cultures, cuisines, and artistic expressions. Its rich historical tapestry, marked by the reign of Hindu Kings, Muslim Sultans, and British colonial governance, has bestowed upon the city a unique ability to adapt and assimilate new cultural influences from across the world. This dynamic cultural receptivity has earned Delhi the moniker 'DilWalo ki Delhi' or 'the lively people's place.'

Within the heart of Delhi, places like Lodhi Colony, Tughlakabad, Khirki Extension, JNU campus, and Hauz Khas Village offer vibrant street art and graffiti, adding to the city's eclectic charm. Delhi, a bustling commercial center in Northern India, embraces diverse sectors like technology, textiles, and more. Its culture blends tradition with modernity, featuring ancient marvels alongside modern skyscrapers, reflecting both heritage and innovation.

Foreign tourists further enrich Delhi's cultural mosaic by bringing their own traditions and values. This interplay of cultures illustrates Edward T. Hall's theory that culture is a complex web of interconnected activities, with roots in the past and constantly evolving through human elaboration. Delhi exemplifies this theory, serving as a cross-cultural destination where history, heritage, and global influences intertwine, creating a city that is both intellectually stimulating and culturally vibrant.

In contrast to Western perceptions of graffiti as a symbol of vandalism or urban decay, India has embraced street art as a form of creative expression. Graffiti artists in India have not only left their marks but also conveyed socio-economic messages through their art. Many, influenced by the societal landscape, have used their craft to comment on various issues.

In 2012, the "Extension Khirkee" project marked a pivotal moment in Delhi's street art scene, organized by artist Aastha Chauhan. This event, supported by the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA), provided a platform for graffiti writers from India and around the world to showcase their skills. The choice of Khirki Village as the location was deliberate, as its less-defined political structures and diverse demographic made it a fertile ground for artistic experimentation.

Subsequently, other art festivals, including the Lodhi Colony Art District, have further promoted street art and brought together artists and performers. The perception of graffiti in India began to shift notably when Anpu Varkey created a monumental mural of Mahatma Gandhi on the Delhi police headquarters, showcasing a contrast to Western graffiti culture.

The St+art festival, initiated in 2016 by the St+Art India Foundation, has been instrumental in bringing street art to the forefront. Supported by organizations like Asian Paints, this festival has transformed public spaces and made art accessible to the masses. It has not only redefined urban spaces but also engaged the public in a dialogue about art.

My newfound admiration and profound appreciation for the significance of street art dawned upon me during a contemplative evening stroll through a seemingly unassuming and tranquil neighborhood in the heart of Delhi. In this capital city, the indelible affinity for art and culture is conspicuously interwoven into the very fabric of its streets. Amidst the awe-inspiring Mughal architectural wonders that grace the cityscape, one can encounter the understated yet captivating murals adorning the walls of Lodhi Colony.

Lodhi Colony, historically recognized as the final housing enclave constructed by the British, exudes an aesthetic of uniformity with its repetitive blocks. However, beneath this seemingly monotonous facade lies the ideal canvas for artistic expression.

The Lodhi Art District emerges as a testament to the city's vibrant cultural landscape, featuring an impressive collection of over 30 artworks contributed by artists hailing from various corners of the globe. These artistic endeavors traverse a diverse spectrum of themes, spanning from poignant social commentaries to celebrations of womanhood, from thought-provoking awakenings to reflections on globalization. The art that graces these walls transcends the mere role of spectatorship; it also pays homage to the very essence of the city itself.

The credit for this transformation goes to the pioneering efforts of the S+Art Foundation, recognized for fashioning India's premier open-air Art District in Lodhi Colony. This initiative has metamorphosed the neighborhood into a resplendent tapestry of vibrant colors, intricate figures, and profound ideas, elevating Delhi's cultural identity and providing an engaging platform for intellectual discourse through artistic expression.

Sneak Peek at Assam

The artistic heritage of Assam, spanning centuries, reveals a rich tapestry of influences, evolution, and resilience. This journey through time commences with the Mauryan stupas discovered at Suryapahar in the Goalpara district, dating back to 300 BC-100 AD, offering glimpses of an ancient artistic inclination. However, it wasn't until the 6th century AD that Assam unveiled more intricate stone and terra cotta artistry.

A notable testament to this era's artistic interplay lies in the exquisite doorframe at Da-Parbatia in Tezpur, reflecting the influence of the Sarnath School of Art during the late Gupta period. It is an embodiment of the cultural exchanges between the realms of Kamarupa and Magadha.

Ancient temples and ruins, such as Madan Kamdev near Guwahati, stand as artistic canvases depicting divine figures, demigods, animals, and even elements of erotica, echoing diverse artistic expressions. However, the zenith of artistic excellence may be attributed to the advent of manuscript painting in the 15th century, an epoch initiated by the luminary Sankaradeva. These manuscripts, while inherently aesthetic, also held profound spiritual connotations. Notably, the Hastividyarnava (a treatise on elephants) and the Chitrabhagawat emerged as seminal works of this era. This period coincided with the reign of the Ahoms, under whose patronage an opulent style of manuscript painting evolved, amalgamating influences from Bengal, and Rajasthan, as well as the Rajput and Mughal traditions of western India.

When exploring the contemporary art culture of Assam, it is a region that retained its medieval artistic essence even during British colonial rule. In the 20th century, artists such as Mukta Bordoloi and Suren Bordoloi, who received training in Kolkata, played pivotal roles in establishing Assam's first art school. Meanwhile, figures like Mitradev Mahanta and Bishnu Prasad Rabha drew inspiration from traditional art forms.

Shobha Brahma and Benu Misra emerged as leaders who blended innovation with the preservation of tradition. Their visionary efforts gave rise to institutions like the Government College of Art and Crafts and the influential Gauhati Artists' Guild. Across the country, in Mumbai, artists like Pranab Barua brought avant-garde concepts to Assam, leaving an indelible mark on the local art scene.

Today, these artists and institutions continue to shape Assam's dynamic and flourishing contemporary art landscape, combining heritage with innovation in remarkable ways.

Presently, a vibrant community of established and emerging artists propels Assam's artistry onto the global stage. These visionaries experiment with a diverse array of mediums, diverging from the traditions of their mentors, thereby championing graphic, psychedelic, installation, and three-dimensional art forms. Their creative endeavors continue to invigorate and redefine Assam's artistic landscape, transcending temporal boundaries to captivate the world.

The burgeoning art collectives in Assam, a phenomenon gaining momentum since the early 2000s, have assumed a pivotal role in mitigating the historical disadvantages faced by the artistic community. Throughout history, collectives have harnessed the power of shared vision while amplifying the individual voices of their members. They serve as crucibles for the creation of both physical and metaphorical spaces where artists discover a sense of belonging and collaboration.

Prior to the advent of a new generation of Assamese artists, the realm of interactive art practices in public spaces remained largely uncharted within the region. These recently-formed collectives have embarked on a mission that delves into the multifaceted socio-political and ecological issues prevalent in the state. Concurrently, they are catalysts for a profound transformation of public perception and imagination through the medium of art. This intellectual and artistic renaissance represents a significant turning point in Assam's cultural landscape.

Delving into the transformative works of Assam's art collectives reveals a realm untethered by political boundaries. The Desire Machine Collective, founded in 2004 by Sonal Jain and Mriganka Madhukaillya and based in Guwahati, embarks on a profound exploration of recurring themes: space-time, the constructivism of memory, and responses to the terrain. Their site-specific project, "Periphery" (2007), ingeniously revitalized an abandoned ferry on the Brahmaputra, seamlessly blending a dysfunctional space into a hybrid alternative hub. This space became a catalyst for global researchers and artists, fostering the exchange of ideas through workshops, residencies, and seminars. "Periphery" encapsulates the ephemeral essence of the river, weaving narratives of everyday life and documenting the personal, non-political history that flows through its two peripherals, North and South Guwahati. It delves deep into the river's profound relationship with energy, sustenance, and human existence, encapsulating the diverse experiences of its inhabitants. As Jahnabi Mitra aptly states, "Recently-formed collectives in Assam have focused on the socio-political and ecological issues of the state, initiating a new public imagination through engagement in the arts."( Art and Ecology: Listening to the voice of art collectives in Assam)

The cultural psyche of the state has always remained intertwined with the river Brahmaputra, a steadfast presence, while the region's politics attached with the river have left a lasting impact. Art, in various forms, becomes a potent tool in political discussions, both as a descriptive force and as a means to transcend the discourse it engages with.

Participatory projects spanning photography, graffiti, street art, and open-access art defy the conventional boundaries of artistic genres, prompting us to question the dichotomy of 'artist versus citizen.' The Anga Art Collective, founded in 2010, serves as a poignant embodiment of the concept coined by Frank Moller—the 'citizen artist.' This concept underscores an equitable emphasis on both "being an artist" and "being a citizen."

The collective's overarching mission is "Art as Activism," a commitment manifested through installations, mural paintings in remote corners of Assam, and the facilitation of dialogues that engage with the socio-political fabric of the region. Notably, Anga Art has harnessed murals as a powerful form of expression from its inception. However, in 2020, their mural depicting Akhil Gogoi—a revered peasant leader and RTI activist from Assam—stirred controversy, facing charges of vandalizing government property. When the collective’s mural of Akhil Gogoi was erased, Anga’a members spoke to VICE India (2020) stating that this incident was an “example of authoritarian, fascistic practices invading the artist’s studio space (the public space as art studio)”. It is important to note that this mural was made in support of Gogoi’s voice during the anti-CAA movement in Assam and his consequent arrest under provisions of UA(P)A.

Within Assam, a tapestry of multidisciplinary artistic communities emerges, each contributing significantly to the artistic landscape. These multifaceted art collectives engage with a diverse spectrum of themes encompassing politics, history, migration, violence, tradition, and the profound connection with the river. Artists bear the profound responsibility of responding to their milieu, and in Assam, the artistic community has been imbued with a profound sense of purpose. These collectives resonate with a resonance that is pregnant with dissent, a voice that resonates with particular urgency in our contemporary era.

Connecting the dots:

Contemplating the intricacies of this metropolitan marvel, i.e Delhi, draws parallels to the diverse artistic neighborhoods in my hometown. Assam, in its artistic endeavors, stands as no lesser a beacon. Recent years have witnessed an efflorescence that has reached every corner of the state, often challenging the disapproval of the administration. From exalting the timeless love story of Dipali and Nilpawan to adorning the canvas of the first-of-its-kind art bridge, from paying homage to the cherished hero of Assamese football to nurturing cultural expressions, from breathing life into art with bougainvilleas to immortalizing the ideals of freedom—Assam's artistic landscape unfolds a myriad of narratives simultaneously.

Neelim Mahanta, a distinguished graffiti artist, has bestowed the walls of public spaces in Guwahati and numerous small towns and villages across Assam with vibrant canvases. As a former student of Delhi College of Arts, Mahanta reminisces in an interview, "In Delhi, I honed my technical finesse and was exposed to the artistic creations of other visionaries." It's plausible that Delhi, with its diverse artistic tapestry, served as the wellspring of Mahanta's inspiration.

A casual stroll along the streets of the capital city, Delhi, has the power to acquaint even an ordinary college-goer like us with the profound sentiments deeply ingrained in our homeland. Preserving these sentiments is an imperative duty. Nevertheless, numerous impediments loom, challenging our cultural inheritance. The suppression of artistic freedom, the apprehension and detention of artists by civic authorities, and the desecration of graffiti-adorned walls all stand as painful aberrations. It is a moral responsibility to safeguard the walls of street art and graffiti.

The burgeoning popularity of this democratized art form has sparked a renaissance, rejuvenating neighborhoods across the globe. The streets of Lodhi Colony, for instance, not only bear witness to artistic endeavors but also symbolize the liberty and freedom inherent in both the creator and the spectator. It is with hope that the Lodhi Art District may serve as an inspiration to us all, igniting a similar artistic fervor in Assam, where creativity and liberty flourish in unison—a testament to the enduring spirit of artistic expression and cultural preservation.

Conclusion:

In a world that's increasingly defined by bustling urban landscapes, the symbiotic relationship between cities and art hubs becomes ever more profound. Delhi, a megapolis steeped in history and culture, has masterfully embraced the language of graffiti and street art, weaving these contemporary expressions into its sociocultural fabric. Simultaneously, Assam, a state in India with a rich artistic heritage, has witnessed the emergence of a burgeoning street art movement that adds new layers to its cultural tapestry.

Delhi, often dubbed the heart of India, pulsates with diversity, both in its population and its artistic expressions. The Lodhi Art District, a testament to this cosmopolitan energy, has become a canvas where artists from around the world converge to convey narratives that transcend borders. Here, vibrant murals and thought-provoking graffiti serve not just as aesthetic embellishments but as conduits for dialogue, reflecting the city's dynamic spirit. These artistic endeavors breathe life into the streets, inviting residents and visitors alike to engage with the socio-political, cultural, and environmental issues they address.

Assam, too, has embraced the transformative power of street art. It has witnessed the rise of collectives and individual artists who, driven by a profound sense of purpose, use their craft to spark discussions on issues ranging from politics to tradition, from migration to the profound connection with the Brahmaputra River. This renaissance in Assam's artistic landscape signifies an intellectual and artistic awakening, echoing a sense of urgency that resonates with the contemporary era.

In the broader context of cities and art hubs, it's evident that street art isn't merely an aesthetic embellishment; it's a catalyst for social change. These art forms have the potential to redefine urban spaces, turning them into more than just concrete jungles. They become vibrant galleries where the public can engage with and be inspired by art. Street art revitalizes neighborhoods, giving them a sense of identity and character. It sparks conversations, challenges the status quo, and fosters a deeper connection between people and their surroundings.

Comparatively, Delhi's Lodhi Art District and Assam's graffiti scene each offer unique insights into the transformative potential of street art. Delhi's embrace of international artists and its position as a cultural melting pot create a rich tapestry of artistic expressions that span the globe. On the other hand, Assam's street art movement is deeply rooted in local issues and traditions, reflecting the region's unique socio-cultural dynamics. This juxtaposition underscores that street art is a versatile medium that can adapt to, and thrive in, diverse environments.

The convergence of street art and urban spaces serves as a powerful reminder that cities are not merely concrete structures but living, breathing organisms shaped by the people who inhabit them. Both Delhi and Assam showcase how art, in its myriad forms, can elevate and enrich the urban experience. They remind us that the streets we walk can be canvases for creativity, conversation, and cultural preservation, reinforcing the profound influence of art in the ever-evolving tapestry of our cities

. . .

REFERENCES:

- KNIGHT, C. K. (2008) Public art: theory, practice and populism, Oxford: Blackwell.

- LACY, S. (1995) Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art.Bay Press, Seattle, Washington

- BERTOLINO, G.; COMISSO, F.; PAROLA, L.; PERLO, L. (eds.) (2008) Nuovi Committenti. Arte contemporanea, società e spazio pubblico, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo

- HEIN, H. (2006) Public Art. Thinking museums differently, AltaMira Press, Lanham.

- Salice,M.K. (2011)"Art Contribution to Cities’ Transformation: The Role of Public Art Management in Italy." ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy, University of Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Italy.

- Milne, Caroline, and Dorina Pojani. (2022)"Public Art in Cities: What Makes It Engaging and Interactive?" Journal of Urban Design, Australia.

- Bhasin, Aparajita. (2018). "The Evolution of Street Art and Graffiti in India." SAUC - Street Art and Urban Creativity 4 (2). https://doi.org/10.25765/sauc.v4i2.149, Portugal

- Chauhan, Bhawna.( 2018). "The Impact of Social-Culture on the Acceptance of Graffiti Art in Delhi.", Impact Journals, India.

- Mitra, Jahnabi. (2023) "Art and Ecology: Listening to the Voice of Art Collectives in Assam." The Chakkar, An Indian Arts review, India

- TG Contributor( 2020) "Art Form of Assam." TOURGENIE SIMPLIFY TRAVEL, Assam.