Introduction:

The 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) was organised recently under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at Glasgow in Scotland from October 31-November 13, 2021. It was scheduled to be held last year at the same venue, but could not be organised due to the Corona pandemic.

Nearly 200 countries participated in the deliberations. The official agenda of the two-week meeting contained primarily to focus on finalizing the rules and procedures for implementation of the Paris Agreement of 2015 which was supposed to have been completed by 2018.

Historical Background of the Climate Change Meetings

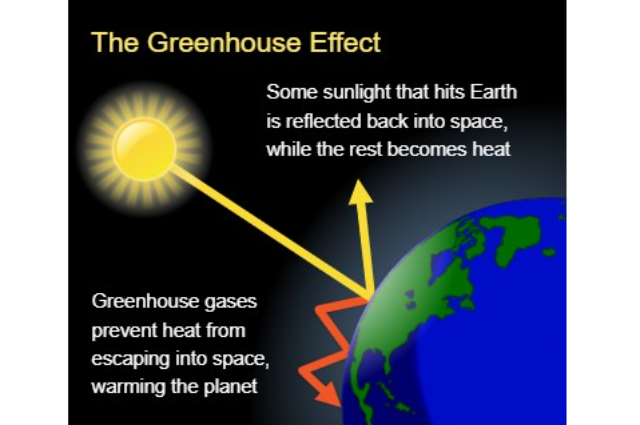

The climate change meetings are the annual affairs as part of an UN-backed process initiated in the early 1990s after the realisation amongst the world community of the fact that greenhouse gas emissions were instrumental in rise in temperature that was likely to make this world uncomfortable to live in. In 1992, the Earth Summit was held at Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, being the first in tackling the menace of climate change gradually affecting the environment of the earth. The meeting at Rio set up the architecture for negotiations on an international climate change agreement. It culminated in finalizing the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the mother agreement laying down the objectives and principles on which climate action by countries were to be based.

The Rio Summit acknowledged that the capabilities and obligations of the developing countries were lesser to bring down emissions than the developed countries. The latter consented to a non-binding commitment to take measures aimed at returning to the emission levels of the 1990s by the year 2020. Further, in 2009, the COP 15 was organised at Copenhagen where the heads of over 110 nations assembled amidst serious differences which seemed too difficult to be bridged. There it was decided to give it a try later. Also, the developed countries committed themselves to mobilize $100 billion every year in climate finance for developing countries from 2020.

Over the years, these meetings have achieved remarkable success in putting the climate change on the top of the global agenda, and ensured that every country has in her armoury, an action plan to tackle climate change. This process gave birth to two international agreements, namely, the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the Paris Agreement in 2015. Both were aimed at curtailing global emissions level. The Kyoto Protocol was the precursor to Paris Agreement. In this Protocol, specific emission reduction targets were assigned for a set of developed countries, to be achieved by 2012. On the other hand, others were supposed to take actions voluntarily in order to reduce emissions. The Kyoto Protocol expired as the new Paris Agreement took its place.

In this connection, COP 13 was held at Bali in Indonesia in 2007 which reaffirmed the principles of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) in an effort to trace a replacement to the Kyoto Protocol with whom the developed nations were not feeling comfortable. This was accentuated with the emergence of China as the world's leading emitter. The logic raised by the developed countries has veered around their approach that the emission reduction targets should be for everyone or for no one. They also argued that in the absence of stringent actions from China and India, the success of any climate action would be impossible to achieve.

At COP 21, known as the Paris Agreement, the successor agreement was finally delivered. This Agreement does not specify emission reduction targets for any country. Rather, it exhorts everyone to do the best-possible efforts in that direction. The targets thus fixed by them must be reported and verified. It distinctly specified the objective being to limit the global rise in temperatures to within 2°C from pre-industrial times. The rules and procedures of the landmark Paris Agreement are still hanging fire as the countries are yet to agree on some of the provisions related to creation of new carbon markets which are an important instrument to facilitate emissions reductions. They were also an integral part of the Kyoto Protocol, which has paved the way for the Paris Agreement.

Under the Kyoto Protocol, a set of rich and industrialised countries were allotted specific emission reduction targets and an indirect way to achieve this was to let countries buy carbon credits from developing countries. Such countries had no targets to reduce emissions under the Kyoto Protocol. However, in case of their willingness and capabilities, they could earn carbon credits. Developed countries could buy these credits and count them towards fulfilling their targets.

On the other hand, the developing countries received payment to finance their endeavours to shift to cleaner technologies. Over the years, developing countries like China, India and Brazil accumulated large number of carbon credits, which at certain point of time were greatly in demand from the developed countries who found an easy way to achieve their targets in a cheaper manner than to reduce their emissions by upgrading their existing industrial facilities. However, the developed countries gradually lost their exuberance. There was a realisation amongst them that non-achievement of their targets did not carry any penalty.

All this resulted in a big drop in demand for carbon credits, and a consequent fall in the price of carbon. Carbon markets are also a part of the Paris Agreement. But a new problem has cast a shadow on its progress. Developed countries argued that they would not allow the transition of the earlier carbon credits to the new market mechanism, claiming many of these were dubious and did not portray the emission reductions accurately. They asked for more robust methods to grant carbon credits. On the contrary, the developing countries are insisting that their accumulated carbon credits which is in billions, remain valid in the new markets. Incidentally, this remains the last stumbling block in the finalisation of the rules and procedures of the Paris Agreement. This is turning out to be a major challenge and objective of the Glasgow meeting.

Issues Before the Meeting and their Outcomes

- The contentious issue of net-zero or carbon neutrality was not mentioned in the Paris Agreement, though it has caught the attention of the world community since then. At present, more than 50 countries have pledged to to carbon-neutrality. China has stated that it would achieve the target by 2060, and Germany is hoping to reach the goal by 2045. India is the largest emitter, but it lacks any commitment to this nature. Several other developing countries have also been resisting such targets. They argue the developed countries are trying to shift their own burden of reducing emissions on to everyone else.

- Prior to the Glasgow meeting, a virtual meeting took place in which ministers of 24 nations calling themselves "Like Minded Developing Countries"(LMDCs), assailed the efforts to force a net-zero target on everyone. They averred that it went against the principles of 'equity' and 'climate justice'. India is a part of LMDC. The developed countries are now calling for all countries to adopt Net Zero targets by 2050. It may further exacerbate the existing inequality between the developed and the developing countries.3 At Glasgow meeting, the concept of net-zero emissions was heavily criticised as meaningless greenwash. In its place, the need for short-term emissions cut (pre-2030 ambition) entered into common parlance.

- Coal has played significant role in fulfilling the need of energy , and has immensely contributed towards the prosperity of the developed nations. Developing countries still need it to accelerate their economic growth. At COP26, at least 29 countries have committed to end public finance for uninterrupted oil, coal and gas by the end of 2022. Thus, COP26 has become the first climate deal to produce a clear plan to reduce coal consumption. However, at the behest of India's last-minute intervention, Parties agreed to change their stance from "phase out" approach to "phase down" in regard to coal-fired power generation.

- China is the world's largest emitter and is likely to take up 33 per cent of the remaining carbon budget for the current decade. It has also not spelt out any target to reduce carbon dioxide. Further, China is using coal heavily and unless it curbs it's coal power production, it will not be carbon neutral. Hence, China was supposed to be focused in this meeting. However, Chinese President did not attend the meeting in person. On the other hand, he was called out by the US President Joe Biden and former President, Barak Obama for not showing high enough ambition. Not only this but also, China signed a joint declaration with the US mentioning enhanced climate actions for near-term ambition in 2020s, and reducing methane emissions. This declaration is lacking in any firm and specific commitment on the part of China. There are no deadlines either. China also went for "phase down" coal consumption in lieu of "phase out" which will start from the year 2026. Thus, the meeting failed in reining in China's self-styled plans to reduce carbon emissions.

- One challenge before the participants was to move ahead of cheap credit panacea. The need of the hour was to suggest some transformational action. In this regard, it may be stated here that the draft text puts an emphasis on the importance of protecting, conserving and restoring nature and ecosystems, including forests and other terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Further, a deal to end deforestation by the year 2030 was signed by more than 100 countries. Also, Article 6 on carbon markets was adopted completing the Paris Agreement rulebook. Thus, not much leeway has been provided for transformational angle.

- The Paris Agreement stipulated that rich nations must transfer US$100 billion annually through 2025 to developing and poor countries to support climate adaptation, mitigation and loss and damage. However, only Germany, Norway and Sweden are paying their shares. Therefore, the flow of real money is elusive enough till now. Moreover, transparency is needed in the flow of climate finance to measure how much and what for this finance was obtained and utilised. But at Glasgow meeting, the developed countries resisted defining climate finance and adding specific language that would signify an increased contribution over and above $100 billion. They also showed their intent to expand donor base and add China. The final text finds expression of "deep regrets" over the failure of developed countries to deliver the promised $100 billion. They are merely asked to arrange this money urgently and through to 2025. The Parties made a commitment to a process to agree on long-term climate finance beyond 2025.

- The adaptation cost is increasing day by day but the flow of funds has slowed down. The Global Goal on Adaptation requires finance over and above networking and information. This meeting was supposed to evolve some way out. As an outcome of this meeting, a two-year work programme was created to assess the progress of the global goal on adaptation. However, no pledge was made to deliver 50 per cent of climate finance for adaptation. The European Union, US, and Canada resisted increasing finance.

- There was a deep flaw in the Paris Agreement in so far as it stated that loss and damage could not be taken as compensation or liability. The COP26 should rework on this point and ensure that the victim nations be compensated accordingly. This agenda should be made permanent in the climate talks. The Glasgow meeting, however, could not make a dent in this regard and did not move beyond reiterating the urgency for scaling up action, including finance, technology transfer and capacity building. It added the provision "that the Santiago network will be supported by a technical assistance facility to provide financial support for technical assistance for the implementation of relevant approaches to avert, minimize, and address loss and damage". In this regard, it may be noted here that US and EU were closed to the idea of a separate loss and damage fund. Only Scotland committed £2 million for loss and damage. So, no headway could be made in this direction.

Points of criticism:

- The text speaks about an independent body to take care of the grievances of affected communities. But it lacks provision in regard to indigenous people's right to free, prior, and informed consent.

- The Glasgow Climate Pact is unlikely to lead the world to the extent of a 1.5°C temperature rise above the pre-industrial levels. It has further highlighted the deep distrust between the rich and poor or the developed and the developing countries.

- At COP26, the world accepted the climate emergency and reiterated limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2030. as agreed, upon under the aegis of Paris Agreement. It also recognised that for this rapid, deep, and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 percent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to net-zero around mid-century, as well as deep reductions in other greenhouse gases will have to be ensured by the countries cumulatively. But there are 98 months left to meet this deadline. According to the latest assessment by non-profit Climate Action Tracker, an independent global action analysis platform, the emission reduction targets by countries now will still lead to 2.4°C warmings. And that appears to be catastrophic as per all scientific analyses.

India's Stand:

India strongly proposed a last-minute change in the final draft by insisting on the use of the term "phase down" in place of "phase out" coal power. This move though accepted, drew much criticism from many quarters. Explaining the situation, Union Environment Minister, Bhupender Yadav stated that, India has never said that it won't go towards green initiatives. India's renewable energy dependency is already at 40%. What is intended is that this action must be according to national circumstances. When the country is setting out a 2070 net-zero target, the commitments have to be according to that. He further said that developed nations should first make climate finance available. All the mitigation done so far is from its own resources. He pointed out that the singular focus on coal and not fossil fuel in toto, including oil and gas which developed nations consume more, would disproportionately impact developing nations which are currently more dependent on coal. It called for a more equitable 'fossil fuel' phase-out instead. Prima facie, India's stand is understandable, but the alternative to coal power must be explored as soon as possible in the interest of humanity as a whole.5

Conclusion:

Since the inception of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting is convened annually to regularly hold discussions on climate change issues. COP26 meeting could be held after a year's delay due to pandemics the world over. Ahead of the Glasgow meeting, the United Nations had set three criteria for success, and none of them could be achieved. These criteria included pledges to cut carbon dioxide emissions in half by 2030, USD 100 billion in financial aid from rich nations to poor, and ensuring that half of that money went to helping the developing world adapt to the worst effects of climate change. The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Gueterres aptly stated that

"We did not achieve these goals at this conference, but we have some building blocks for progress".This statement best summarises the outcome of the Glasgow Climate Meeting. Developing countries remained dissatisfied with the attitude of the developed countries in many respects. Also, nothing concrete could be achieved in this meeting. Though substantial progress has been made in regard to formulation of rules regarding Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, it lacks consensus among nations and the differences have not been sorted out fully. However, the efficacy of such annual meetings can not be evaluated on the basis of big achievements. These are the small steps to break the ice and prepare grounds for big deals. In the backdrop of the impending climate crisis, the role of Glasgow meeting can not be undermined. The dialogue on such an important issue must continue at any cost.

. . .

References:

- COP 26, What The Glasgow Climate Pact Means For The Rapidly Warming Planet And Its People, Richard Mahapatra and Snigdha Das, Avantika Goswami, Down To Earth, p.29, 16-30 November, 2021.

- Ibid, p.30.

- Amitabh Sinha, The Agenda for Glasgow, The Indian Express, October 25, 2021.

- COP 26, What The Glasgow Climate Pact Means For The Rapidly Warming Planet And Its People, Richard Mahapatra and Snigdha Das, Avantika Goswami, Down To Earth, p.37, 16-30 November, 2021.

- Anubhuti Vishnoi, India Never Said Won’t Move to Green Initiative: Bhupender, The Economic Times, November 15, 2021.