Sudan, one of Africa’s largest and most diverse nations, has been plunged into a devastating civil war since April 2023. The conflict, sparked by a power struggle between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), has led to a humanitarian disaster on a scale not seen in decades. Although the war is political rather than religious in nature, Sudan’s population is overwhelmingly Muslim—around 97 per cent—meaning that the civilian suffering primarily affects Muslim communities. Over two years of conflict have torn apart families, destroyed infrastructure, and left millions without food, shelter, or healthcare. According to the United Nations, the crisis has displaced more than 10 million people inside and outside the country, making it the world’s largest displacement crisis in 2025.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Sudanese civil war from 2023 to 2025. It examines the origins and evolution of the conflict, its humanitarian consequences, the political and military dynamics at play, the international response, and the lived experiences of ordinary Sudanese Muslims caught in the crossfire. The aim is to present a clear, factual, and human-centred picture of one of the most tragic conflicts of the modern era.

Background of the Conflict

The roots of Sudan’s current conflict can be traced back to its turbulent political history. After decades of authoritarian rule under President Omar al-Bashir, mass protests in 2019 forced his removal from power. A fragile transitional government was then established, combining civilian leaders and military figures who promised democratic reform. However, tensions between the military and civilian leadership quickly emerged. The two most powerful military leaders—General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sudanese Armed Forces, and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as “Hemedti,” commander of the Rapid Support Forces—became rivals for control.

In October 2021, General Burhan staged a coup, dissolving the transitional government and arresting civilian leaders. While Burhan promised a return to democracy, the move deepened divisions within the armed forces and alienated much of the population. The RSF, a paramilitary organisation that evolved from the notorious Janjaweed militias of the Darfur conflict in the 2000s, grew increasingly powerful. The RSF controlled vast gold mines and enjoyed strong financial backing, allowing it to operate almost as a parallel army. When efforts to integrate the RSF into the national army stalled, tensions escalated into open warfare in April 2023.

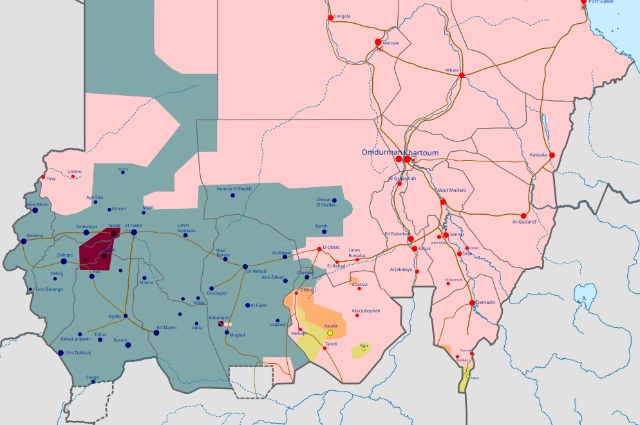

Fighting broke out in Khartoum, the capital, as RSF units attacked key military sites. The violence quickly spread to other regions, including Darfur, Kordofan, and the eastern states. By mid-2024, both factions had established competing zones of control. The SAF held parts of central and eastern Sudan, while the RSF dominated large portions of Darfur and the western regions. This fragmentation of authority has made governance impossible, leaving millions trapped in areas cut off from basic services.

The conflict also reflects broader struggles over identity, power, and economic resources. Sudan is ethnically and regionally diverse, and historical grievances have long existed between its Arabized elites and marginalised non-Arab populations. The RSF’s recruitment from Arab tribes in Darfur, and its alleged targeting of non-Arab Muslim communities, have revived fears of ethnic cleansing reminiscent of the early 2000s atrocities. In this sense, the civil war is both a political and social tragedy rooted in unresolved historical injustices.

Humanitarian Crisis and Impact on Muslims

The humanitarian consequences of the Sudan civil war are staggering. Nearly half of the country’s 50 million people now require humanitarian assistance. The war has destroyed markets, hospitals, schools, and transport systems, leaving millions dependent on aid that cannot reach them due to insecurity. More than 18 million people face acute food insecurity, with several regions already experiencing famine conditions. In parts of North Darfur, families survive on one meal a day, often made from wild grains or leaves. Malnutrition has become widespread, particularly among children. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) warns that over three million children are acutely malnourished, and at least 700,000 could die without urgent intervention.

Muslim civilians—farmers, traders, mothers, and children—bear the heaviest burden of the crisis. Sudan’s social fabric, historically woven through Islamic traditions of hospitality and community support, has been shattered. Entire Muslim villages have been burned, and mosques destroyed. In Darfur, Muslim non-Arab tribes such as the Masalit have faced mass killings and displacement. The U.S. government in early 2025 determined that these attacks by RSF-aligned militias constituted acts of genocide. Eyewitnesses describe horrific scenes: men executed in front of their families, women subjected to sexual violence, and children separated from their parents as they fled burning villages.

Beyond direct violence, the collapse of public health and education systems has deepened the suffering. Over 80 per cent of hospitals in conflict areas are non-functional. Outbreaks of cholera, measles, and malaria have spread rapidly due to a lack of clean water and sanitation. Religious charities and local Muslim aid organisations, which traditionally play a major role in community welfare, have been overwhelmed or forced to shut down due to insecurity. Ramadan and Eid, once occasions of community celebration, have turned into periods of mourning in many parts of the country. In displacement camps, imams now lead prayers over rows of graves for those who have died from hunger or disease.

International aid agencies struggle to operate in the dangerous environment. Relief convoys are frequently looted, and aid workers have been targeted. The World Food Programme reported multiple attacks on its warehouses, resulting in the loss of tons of food supplies. As both sides use access to aid as a weapon of war, millions remain unreachable. The suffering of Muslims in Sudan, therefore, is not only a byproduct of war—it has become a deliberate consequence of military and political strategies.

Political and Military Developments

The military situation in Sudan has evolved dramatically since the outbreak of war. Initially, the RSF gained the upper hand in urban areas such as Khartoum due to its mobility and guerrilla tactics. The SAF, relying on heavy artillery and air strikes, responded with intense bombardments that devastated neighbourhoods. Civilians were trapped amid crossfire, with many forced to flee on foot. By early 2024, the front lines had hardened, creating a de facto partition of the country. The RSF maintained control over most of Darfur and parts of the capital, while the SAF consolidated its positions in the east.

Foreign involvement has further complicated the conflict. Reports indicate that Egypt and Iran have provided varying levels of support to the SAF, while the RSF has received backing from elements within the United Arab Emirates and the Wagner Group from Russia. Sudan’s gold trade has also become a source of financing for the RSF, fueling international smuggling networks. This foreign entanglement risks turning Sudan into a proxy battleground, prolonging the war and reducing incentives for peace.

Politically, both factions claim to represent Sudan’s legitimate government. The SAF maintains its headquarters in Port Sudan and insists that it is defending national unity. The RSF portrays itself as a revolutionary force fighting for marginalised regions. However, both sides have been accused of war crimes and corruption. Civilian groups that once championed democracy have been sidelined or silenced. International mediators, including the African Union and the United States, have hosted multiple rounds of ceasefire talks, most notably in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, but none have produced lasting results.

The stalemate has devastated governance structures. Civil administration has collapsed, and regional authorities often operate independently. The economy has also crumbled, with inflation soaring above 250 per cent. The Sudanese pound has lost most of its value, and salaries for civil servants, including teachers and doctors, remain unpaid. The breakdown of national institutions has allowed armed groups and criminal networks to flourish, particularly in border regions where weapons and goods move freely. Without a unified authority, Sudan risks total state failure—a scenario that would endanger the entire Horn of Africa.

International Response and Challenges to Peace

The international community has responded to Sudan’s crisis with concern but limited effectiveness. The United Nations, the African Union, and the Arab League have all called for ceasefires and humanitarian corridors. Neighbouring countries such as Egypt, Chad, and South Sudan have struggled to absorb millions of refugees fleeing the fighting. Camps in eastern Chad now host over 1.5 million Sudanese refugees, many living in tents without adequate food or medicine.

The United Nations Security Council has debated stronger intervention, but global divisions have hampered decisive action. Western powers, including the United States and the European Union, have imposed sanctions on individuals accused of atrocities, while Gulf countries have sought to mediate peace. However, competing geopolitical interests have diluted collective action. The U.N.’s ability to deliver aid remains constrained by a lack of funding—only 40 per cent of the 2024 Humanitarian Response Plan was financed.

Human rights organisations have urged the International Criminal Court to investigate alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity. The ICC has issued warnings that both SAF and RSF leaders could face prosecution if evidence continues to mount. Yet, justice remains distant as both factions retain significant power and continue to defy international pressure. The humanitarian dimension of the crisis—famine, disease, and displacement—has often overshadowed the urgent need for political accountability.

Religious institutions worldwide, including Muslim organisations, have called for solidarity with Sudan’s people. Appeals for prayer, fasting, and charity have circulated widely, particularly during Ramadan. However, without secure access and sustained funding, even global compassion has a limited practical impact. The challenge for the world remains how to translate moral outrage into concrete support for peace and recovery.

Voices from the Ground: Stories of Survival

Beyond statistics and political statements lie the personal stories of those enduring unimaginable hardship. In a displacement camp near Nyala, a mother named Fatima recounts how her village was burned. Her husband was killed, and she walked for three days carrying her two children to reach safety. “We had nothing to eat but wild fruits,” she says. “Now we pray for peace, but every night we hear gunfire.”

In another camp in North Darfur, a 14-year-old boy named Ahmed volunteers to help distribute food. He dreams of becoming a doctor, but the school he attended was destroyed. “When the planes bombed, I ran and never saw my friends again,” he says quietly. His story mirrors those of thousands of young Sudanese whose futures have been shattered.

Imams and community elders continue to play vital roles in maintaining hope. In many camps, Friday prayers are the only organised activity bringing people together. Religious leaders speak about patience and faith, reminding displaced Muslims that endurance is part of their spiritual duty. Local women’s groups also organise communal cooking when food arrives, ensuring that even strangers are fed. Despite the immense suffering, these gestures of solidarity reveal Sudan’s resilience and faith in humanity.

The voices of aid workers echo the same plea. “We are running out of supplies, but not out of compassion,” says a Sudanese nurse working with the Red Crescent. Her words summarise the spirit of thousands risking their lives to help others. Their courage, often unreported, represents the flickering light of hope in a dark chapter of human history.

The civil war in Sudan between 2023 and 2025 is a profound human tragedy. What began as a struggle between two generals has evolved into a nationwide catastrophe that threatens to erase decades of social and economic progress. The war has turned homes, schools, and mosques into ruins, and driven millions of Muslims—men, women, and children—into hunger and exile. It has fractured communities that once lived in harmony and unleashed famine and disease on an unprecedented scale.

Yet amid despair, there remain reasons for hope. Sudan’s people continue to show courage, faith, and solidarity even in the darkest circumstances. The world, however, must do far more. A sustainable peace will require genuine international commitment, pressure on the warring parties, and massive humanitarian assistance. The global Muslim community, in particular, bears a moral responsibility to stand with Sudan’s suffering believers.

The lessons of Sudan’s war are clear: when political ambition outweighs human compassion, nations collapse. Peace cannot come from victory on the battlefield but from justice, reconciliation, and a shared determination to rebuild. For Sudan’s Muslims—and for humanity as a whole—ending this war is not just a political necessity but a sacred duty.

. . .

References: