The Kaveri River, known as the lifeline of southern India, has been a source of contention between the states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu for decades. The dispute over the sharing of Kaveri's waters has led to a series of conflicts, both legal and political, often referred to as the Kaveri Water Dispute. Among these conflicts, the Kaveri War stands out as one of the most intense and significant periods of tension between the two states.

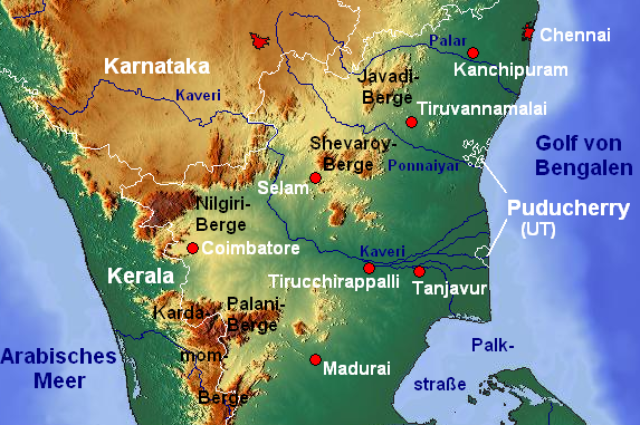

The Kaveri River originates in Karnataka's Kodagu district and flows through Karnataka and Tamil Nadu before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. The river basin supports extensive agriculture in both states, with farmers relying heavily on its waters for irrigation. However, the monsoon-dependent nature of the river means that water availability fluctuates, leading to conflicts over its distribution during times of scarcity.

Historically, agreements and treaties attempted to address the allocation of Kaveri's waters between the riparian states. However, disputes continued to arise due to variations in rainfall, increasing demand for water due to urbanization and industrialization, and changes in agricultural practices. The inability to reach a lasting and equitable solution fueled tensions between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, eventually escalating into the Kaveri War.

The Kaveri War erupted during a particularly dry period when water levels in the river were significantly low. Karnataka, facing agricultural distress, decided to divert more water from the river to meet the needs of its farmers, especially in the drought-prone regions of the state. Tamil Nadu, heavily dependent on Kaveri's waters for its agriculture, vehemently opposed Karnataka's actions, claiming that it violated established agreements and would severely affect Tamil Nadu's farmers.

The conflict quickly escalated, with both states resorting to legal, political, and even public protests to assert their claims over the river's waters. The Supreme Court of India intervened, issuing directives and orders to regulate the distribution of Kaveri's waters and urging the states to find an amicable solution. However, these interventions often failed to address the underlying issues satisfactorily, leading to further tensions.

The Kaveri War witnessed widespread protests, demonstrations, and even instances of violence in both Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. Farmers, the backbone of the agrarian economies in both states, were deeply affected by the water scarcity and the uncertainty surrounding its availability. The conflict also strained inter-state relations, affecting trade, transportation, and social cohesion between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

Efforts to resolve the Kaveri Water Dispute have been ongoing for decades, involving negotiations, tribunals, and mediation by the central government. However, a lasting solution has remained elusive, with each proposed agreement facing challenges in implementation and acceptance by the riparian states.

In recent years, there have been attempts to promote cooperative measures such as water conservation, rainwater harvesting, and the modernization of irrigation techniques to mitigate the impact of water scarcity in the Kaveri basin. Additionally, there have been calls for a more holistic approach to water management, considering the needs of all stakeholders, including farmers, urban dwellers, and industries.

The Kaveri War serves as a stark reminder of the complex challenges posed by transboundary water disputes and the urgent need for sustainable water management practices. As climate change exacerbates water scarcity and variability, the importance of resolving such conflicts through dialogue, cooperation, and innovative solutions becomes increasingly evident. Ultimately, the equitable sharing of Kaveri's waters requires a collective commitment to stewardship and shared prosperity, transcending regional boundaries and political differences.

Because of Karnataka's lacklustre southwest monsoon this season, the competition between the upper riparian state, Karnataka, and the lower riparian state, Tamil Nadu, which shares 404.25 tmc (thousand million cubic feet) annually, has gotten worse. Over the years, judicial and quasi-judicial bodies established to address the problems have fallen short. Both states are still fighting for their proper portion of the river's water, so a long-lasting solution is still required. The main research findings that must direct the dispute resolution processes are the subject of this article. Given the climate crisis, it is imperative that we support both states' reasonable shares of water conservation measures rather than their respective rightful shares of water.

According to Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase, the two states could negotiate freely to divide the river water in an efficient manner if there are minimal transaction costs and well-defined property rights. However, effective negotiation is impossible due to the political, high transaction costs, and historical complexity of the dispute.

Rather, the perspective of the Tragedy of the Commons is invoked, emphasising the danger of excessive utilisation and exhaustion of the Cauvery River as a shared resource in the absence of sufficient regulation or property rights. This viewpoint recognises the problem of collective action, where individual interests can result in less than ideal outcomes for the states and the environment, and emphasises the necessity of government intervention and regulatory mechanisms to prevent the Tragedy.

Transboundary water disputes often involve upstream states applying the Harmon doctrine, while downstream states prioritize primary water rights for historical users. International guidelines can help ensure equitable and reasonable use of transboundary waters. The 2018 Supreme Court judgement on Karnataka's appeal discussed the water-sharing formula in the Cauvery basin, based on Helsinki, Berlin, and Compoine rules. The full yield figure was estimated at 740 tmc, with 14 tmc allocated for environmental protection and sea flows. The judgment also noted that rainfall, flows, and crop patterns determine water release during distress.

The water-sharing formula should incorporate a water conservation strategy, reflecting the shared responsibility of states towards Cauvery as a property. This includes investments in irrigation efficiency, cropping diversion, water conservation, and measures to regulate water demand. When water supply is constrained and shortages are recurrent, conserving scarce resources should be prioritized over subsidizing agriculture for redistributive justice. Diversifying crop patterns in the Cauvery Delta can help manage demand for irrigation. Promoting crop diversification through a minimum support price regime favoring drier crops, millets, horticulture, and oilseeds can encourage less water-intensive crops in both states.

Water conservation is often neglected by Indian states, with Bengaluru ranking second in water wastage. Despite receiving a $100 million loan from the Asian Development Bank to reduce water stress in the Cauvery Delta, water demand persists. Water pollution in the Cauvery Basin, including pharmaceutical contaminants, industrial effluents, untreated sewage, and agricultural runoff, is also a concern. To resolve the Cauvery dispute, water demand management and conservation are crucial. Prioritizing the preservation of catchment areas and river basins is essential for sustainable water supply. The politicization of water resources has exacerbated the dispute, and shifting focus from water sharing to conservation is crucial.

Stakeholders must recognize the need for a new narrative prioritizing sustainable water use, minimizing ecological harm, and embracing climate change challenges. Legal requirements advocating for water conservation and demand management are the only lasting solution to the age-old conflict.