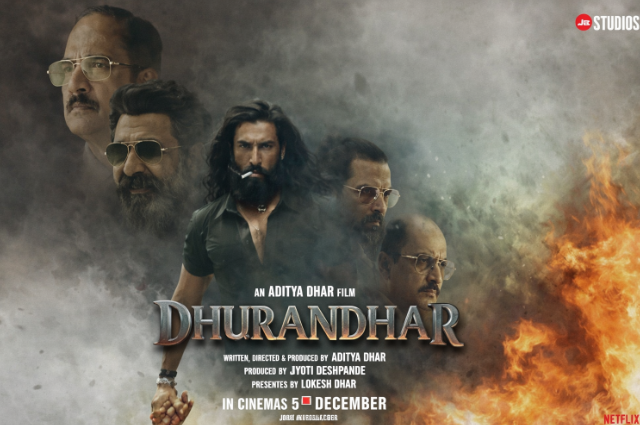

For a long time, going to the movies had begun to feel optional. Cinema halls were no longer the first choice; they were a backup plan. Weekday shows ran half-empty, excitement around releases faded quickly, and many films found their audience only after arriving on OTT platforms. The collective experience of watching a film on the big screen—once central to Indian cinema culture—seemed to be slowly losing relevance. Then Dhurandhar released, and something unexpectedly shifted.

What stood out was not just the opening weekend rush, but what followed. Cinema halls continued to remain full weeks after release. Viewers returned for repeat watches, group bookings increased, and theatres once again felt like spaces of shared excitement rather than quiet rooms. The film became more than a one-time watch; it turned into an event people wanted to relive.

The success of Dhurandhar goes beyond impressive box office collections. It reflects a larger change in audience behaviour and signals a renewed appetite for the theatrical experience. At a time when the future of cinema halls was being questioned, Dhurandhar has reopened an important conversation—about why the big screen still matters and what it takes to bring audiences back again and again.

When Theatre-Going Became a Habit Again:

These days, people wait for festivals, long weekends, or “big” releases to justify the effort of watching films in a theatre. Otherwise, films were saved for later—watched at home, broken into parts, or scrolled past entirely. Cinema halls slowly adjusted to this reality, growing used to half-filled weekday shows and brief bursts of weekend crowds. Then Dhurandhar arrived and quietly disrupted this pattern.

What stood out was not just the initial rush, but the consistency that followed. Weekday shows that were once easy to ignore began filling up again. People stopped waiting for the “perfect time” and simply went to the theatre because they wanted to. Families planned mid-week outings, friends made last-minute bookings, and solo viewers walked in without overthinking ticket prices or show timings. The decision to watch a film on the big screen felt effortless again.

More importantly, theatre-going no longer felt like a one-time commitment. Viewers returned for second and even third watches, often bringing along someone new each time. This wasn’t driven by hype or pressure, but by enjoyment. The film created an experience people wanted to relive—something that felt better shared than watched alone. Conversations around the movie extended beyond social media and into everyday plans, influencing when and how people chose to spend their free time. In doing so, Dhurandhar restored something that had slowly faded: spontaneity. Cinema visits were no longer carefully scheduled or justified as a “special treat.” They became casual again, woven into normal routines. This shift matters because habits shape industries more than trends do. A film that rebuilds the habit of theatre-going does more than succeed commercially—it reshapes audience behaviour.

Perhaps the real impact of Dhurandhar lies here. It reminded people that going to the movies does not always need a reason. Sometimes, it can simply be a choice made on an ordinary day, for the joy of the experience itself.

Repeat Viewership: The Real Measure of Impact

Watching a film once is easy. It can be driven by curiosity, marketing, or the fear of missing out. What truly sets a film apart, however, is the audience’s decision to return. Repeat viewership is not accidental—it reflects a deeper connection between the film and its viewers. In the case of Dhurandhar, this connection became increasingly visible as people chose to watch the film again, sometimes within days of their first viewing.

What motivated these repeat visits varied from person to person. For some, it was the performances that lingered long after the credits rolled, revealing new layers on a second watch. Others returned for the music, the background score, or specific scenes that felt more powerful on the big screen than they ever could on a mobile device. Many viewers admitted that while the story drew them in initially, it was the overall experience—the sound, visuals, and collective reactions—that pulled them back into theatres.

Repeat viewing also transformed the way people watched the film. The first visit was often about following the narrative; the second allowed audiences to notice details they had missed earlier. Dialogues, expressions, and subtle moments gained more meaning. This made the film feel richer with every viewing, rewarding those who invested their time again. Such engagement is rare in an era where content is consumed quickly and forgotten just as fast.

From an industry perspective, repeat viewers are far more significant than opening-day crowds. They sustain box office collections beyond the initial surge and keep theatres occupied well into later weeks. More importantly, they signal trust. When audiences return, they are not responding to promotion—they are responding to satisfaction. This kind of loyalty cannot be manufactured; it has to be earned.

Ultimately, the repeat viewership of Dhurandhar highlights its true impact. The film did not rely solely on novelty or hype. It stayed with people, prompting them to relive the experience and share it with others. In doing so, it proved that lasting success in cinema comes not from being watched once, but from being remembered—and chosen—again.

More than Numbers: What the Box Office Really Indicates

Box office collections are often reduced to headlines and comparisons—opening day figures, weekend totals, records broken or missed. In this rush to quantify success, what often gets overlooked is what these numbers actually represent. In the case of Dhurandhar, the real story does not lie merely in how much it earned, but in how consistently it continued to earn. The film’s sustained performance reveals far more than any opening-day statistic ever could.

From OTT Comfort to Theatre Excitement:

Over the last few years, OTT platforms quietly reshaped how people consumed cinema. Films became convenient—available anytime, anywhere, and often cheaper than a single theatre ticket. Watching a movie no longer required planning; it could be paused, replayed, or abandoned midway without consequence. While this comfort suited modern lifestyles, it also changed the relationship audiences had with films. Cinema slowly became background content rather than an immersive experience.

As this habit settled in, a sense of fatigue followed. Endless options led to shorter attention spans. Viewers scrolled longer than they watched, frequently switching between titles without fully engaging with any. Many films, despite strong storytelling, felt oddly forgettable when viewed on small screens. The emotional highs were muted, the visual scale reduced, and the silence of solitary viewing replaced what was once a collective reaction. Something essential to cinema was missing.

Dhurandhar arrived at a moment when audiences were ready to feel that absence. The film demanded attention in a way that home viewing could not fully offer. Its visuals, sound design, and pacing felt deliberately crafted for the big screen. Watching it in theatres was not just about seeing the story unfold—it was about feeling it. The surround sound, the darkened hall, and the shared anticipation amplified moments that might otherwise have passed quietly at home.

What truly set the experience apart was the presence of other viewers. Laughter, gasps, and silence were shared rather than isolated. Reactions became contagious, turning scenes into moments and moments into memories. This collective engagement reminded audiences why cinema halls once held such cultural importance. The film was not merely consumed; it was experienced together. In this sense, Dhurandhar functioned as “event cinema.” It was not something to casually add to a watchlist for later. It encouraged people to step out, buy tickets, and participate in a communal experience. This distinction matters because it highlights the unique strength of theatres—something OTT platforms, despite their convenience, cannot replicate.

The shift from OTT comfort back to theatre excitement does not suggest rejection of digital platforms. Instead, it reflects a rebalancing. Audiences still value convenience, but they also crave experiences that feel complete and impactful. Dhurandhar demonstrated that when films respect the theatrical medium, audiences are willing to return to it. Theatres, after all, offer not just a screen, but a shared emotion—something no pause button can replace.

Audience Behaviour in terms of Data:

In discussions around cinema success, audience reactions are often dismissed as emotional or subjective. Excitement, praise, repeat watches—these are usually seen as feelings rather than facts. However, when viewed closely, audience behaviour itself becomes a powerful form of data. The response to Dhurandhar offers a clear example of how collective viewing choices can reveal deeper economic and cultural patterns within the film industry.

One of the most visible indicators was theatre footfall. Footfalls are not abstract metrics; they represent real people making deliberate decisions to leave their homes, purchase tickets, and spend time in cinema halls. In recent years, declining footfalls have signaled reduced confidence in theatrical releases. Dhurandhar reversed this trend, not just during its opening days but consistently over time. Sustained occupancy rates, especially during weekdays, pointed to demand that went beyond curiosity. This consistency is critical because it reflects audience commitment rather than momentary hype.

Repeat visits further strengthened this behavioural evidence. When viewers choose to watch a film more than once, they are making a conscious economic decision. A repeat ticket is not a default choice in an era of abundant and inexpensive digital content. It indicates that the experience delivered sufficient value to justify additional spending. These repeat visits act as qualitative confirmation of satisfaction, transforming personal enjoyment into measurable market behaviour.

Another significant shift was the role of word-of-mouth. Traditionally, high marketing budgets have driven opening-week collections, often masking the film’s actual reception. In the case of Dhurandhar, audience conversations played a central role in sustaining interest. Recommendations circulated organically—through personal interactions, social media discussions, and shared viewing plans. This organic promotion reduced dependence on aggressive advertising and instead relied on trust between viewers. Word-of-mouth, in this context, functioned as an informal yet credible information network influencing consumer behaviour. Viewing choices, therefore, became economic signals rather than casual preferences. Each ticket purchase represented a calculation—balancing time, money, and expectation of value. When thousands of individuals independently arrived at the same decision, a pattern emerged. This pattern communicated confidence in the film and, by extension, in the theatrical experience itself. Such behaviour challenges the assumption that audiences prefer convenience over quality. Instead, it suggests that viewers are willing to invest when they believe the return will be worthwhile.

Seen through this lens, Dhurandhar was not merely watched; it was evaluated continuously by its audience. Attendance, repeat visits, and recommendations together formed a feedback loop that sustained its success. These behaviours provided the industry with actionable insight: audiences are not disengaged, but discerning. They respond to authenticity, scale, and emotional payoff.

Ultimately, the response to Dhurandhar demonstrates that audience behaviour is not noise—it is evidence. When people “vote” with their time and money, they generate data that speaks louder than surveys or projections. This case study reinforces an important truth for the film industry: understanding audiences does not begin with assumptions, but with observing how they choose to act.

The Economic Ripple Effect on Cinema Halls and Local Businesses:

When a film like Dhurandhar draws audiences back to theatres consistently, its impact goes far beyond ticket sales. Single screens and multiplexes, which often operate on tight margins, benefit immediately from higher occupancy. Every show that fills its seats contributes not just to revenue but to the confidence of theatre owners, who can plan screenings and staffing more effectively. In many ways, the success of a single film becomes a financial lifeline for these establishments, helping sustain them through periods when footfalls are otherwise unpredictable.

The ripple effect extends to the smaller businesses that thrive around cinemas. Concession counters sell more popcorn, nachos, and beverages; local eateries see an uptick in customers; parking lots and transport services experience higher demand; even small vendors outside the theatre enjoy a surge in sales. These micro-economies, often overlooked, depend on consistent theatre attendance. A hit film effectively boosts this entire ecosystem, showing how entertainment and local business are intertwined in ways that benefit the community as much as the film industry itself.

Beyond immediate profits, the sustained economic activity has longer-term implications. Consistent revenue streams encourage theatre owners to invest in maintenance, better facilities, and improved viewing experiences. Local businesses, sensing opportunity, adapt to meet audience needs more efficiently. In this way, the success of Dhurandhar demonstrates that cinema is not just an isolated cultural experience—it is a driver of economic activity. One film, therefore, becomes a catalyst, revitalizing theatres and the surrounding community alike. Its impact reminds us that when audiences show up, the benefits are shared widely, reinforcing the importance of theatrical releases in the broader cultural and economic landscape.

Patterns Behind Audience Trust:

The success of Dhurandhar is not just a story of box office numbers; it is a story of audience trust and calculated engagement. In recent years, several films with massive marketing budgets and star power failed to sustain theatre attendance beyond the opening weekend. Audiences had become selective, increasingly unwilling to spend time and money on films that promised spectacle but failed to deliver genuine content. Dhurandhar, by contrast, managed to win repeated visits and sustained footfalls because viewers felt confident that their investment—both in terms of time and money—would be rewarded. In this sense, audience behaviour itself became a form of evidence, highlighting patterns that the industry can no longer ignore.

One of the most important factors behind this trust was word-of-mouth and personal recommendation. Unlike many films that rely heavily on pre-release marketing hype, Dhurandhar generated organic buzz. Viewers discussed the film not just online but within social circles, sharing specific scenes, performances, and experiences that made the film feel worth seeing on the big screen. This informal communication acted as a reliable signal for new audiences, reducing the perceived risk of a theatre visit. When people repeatedly choose to watch a film based on peer validation and past positive experiences, it demonstrates that trust is measurable, repeatable, and central to sustainable theatrical success.

Another pattern that emerges from the response is the importance of content aligning with audience expectations. While OTT platforms offer convenience, audiences now prioritize films that give them something they cannot experience at home—scale, sound, and collective engagement. Dhurandhar delivered on these elements consistently, earning credibility in the process. The industry lesson is clear: repeatable success does not rely on hype, celebrity presence, or occasional spectacle alone. It depends on building a relationship of trust with the audience, understanding their expectations, and delivering an experience that validates their choice to step out. Observing these patterns makes Dhurandhar not just a hit, but a case study for filmmakers and exhibitors looking to revive theatre attendance in a sustainable, long-term way.

Industry Lessons & Trust Rebuilding:

The success of Dhurandhar offers more than just a moment of celebration for producers and theatre owners—it serves as a clear lesson in rebuilding audience trust, which has become the most valuable currency in today’s film industry. Over the past few years, audiences grew cautious; repeated disappointments and underwhelming releases had made them hesitant to spend time and money in theatres. Dhurandhar demonstrates that when a film respects the audience’s expectations and delivers a consistently engaging experience, trust can be regained. This lesson is crucial: theatrical success is no longer guaranteed by star power or marketing alone—it must be earned through content that feels worth the effort.

For filmmakers, the takeaway is that the theatrical medium still matters, but only when the film is designed for it. Dhurandhar succeeded because every element—from narrative pacing to visual storytelling—was crafted to maximize the big-screen experience. The story resonated, the performances felt layered, and the technical aspects enhanced immersion rather than distracting from it. These are measurable factors that studios and creators can study. Future films aiming for theatre-first success will need to consider not just plot or hype, but how every scene and moment will impact the viewer sitting in a crowded hall, sharing reactions with others. The audience no longer tolerates mediocrity disguised as spectacle; they reward consistency, authenticity, and engagement.

Exhibitors and theatre owners also gain important insights. The return of full halls, sustained across multiple weeks, shows that audiences respond positively when theatres offer reliability and comfort alongside content. Investing in a welcoming viewing experience—clean facilities, good sound, and attentive service—amplifies the effect of strong content. Additionally, monitoring audience behaviour, such as repeat visits and word-of-mouth patterns, can help theatres anticipate demand and plan better. In this way, Dhurandhar has become more than a commercial success—it is a practical blueprint for rebuilding confidence between creators, exhibitors, and viewers.

Ultimately, the film illustrates that the revival of theatre-going is possible, measurable, and repeatable, but only when trust is prioritized. For the industry, this is both a challenge and an opportunity: deliver content that earns attention, and audiences will not just return once—they will come back again and again. Dhurandhar is proof that theatres are not obsolete; they thrive when audiences feel valued, understood, and rewarded for choosing the big screen experience.