Kota, often dubbed the "Mecca of Coaching," is synonymous with ambition, discipline, and the pursuit of academic excellence. It stands as the epicenter of India's private coaching industry, home to more than 300 coaching institutes that specialize in preparing students for highly competitive exams like NEET and IIT-JEE. Each year, nearly 2 lakh students migrate to this bustling city, driven by the hope of transforming their dreams into reality.

The infrastructure of Kota is meticulously built around its coaching culture: sprawling campuses, cramped hostels, PG accommodations, libraries open 24/7, and a network of messes and food delivery services tailored to students’ schedules. The entire city's economy thrives on this single demographic: teenagers chasing entrance exam success.

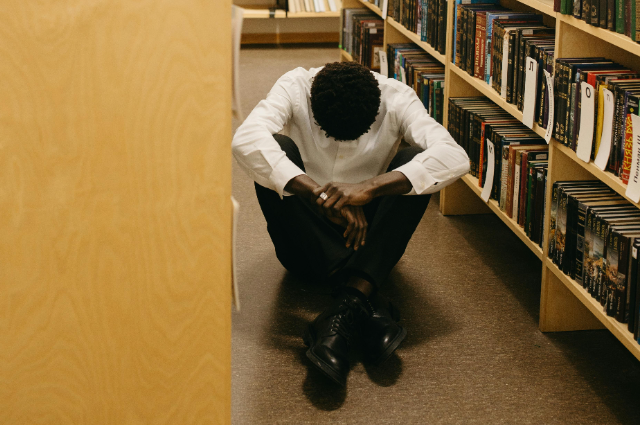

Yet, hidden beneath the facade of success stories and rank-holders is a haunting reality. The mounting academic pressure, emotional isolation, and the burden of expectations are taking a brutal toll on the mental health of these young aspirants. The relentless routine, long study hours, and a cutthroat competitive environment leave little room for social connection, recreation, or emotional resilience.

And when the weight becomes too much to bear, some students take the most tragic route — suicide. The rising number of such cases has cast a long, dark shadow over Kota’s reputation. In recent years, the city has witnessed a surge in student suicides, with 26 reported in 2023, and 15 more by mid-2025. Each death is not just a statistic, but a poignant reminder of a systemic failure — a failure to recognize mental health as equally important as academic performance.

Why is a city built on dreams turning into a graveyard of unfulfilled potential? What drives these bright young minds, many of them at the threshold of adulthood, to such despair? And most importantly, how long can a system that glorifies results over well-being sustain itself?

These questions demand urgent answers, for behind every toppers’ poster plastered across Kota’s walls lies a silent story — one that is often overlooked, but must no longer be ignored.

A Grim Statistic: The Rising Toll

In 2025 alone, Kota has already recorded 15 student suicides — each one a devastating reminder of the emotional toll the city extracts from its young aspirants. The most recent tragedy involved a NEET aspirant from Jammu and Kashmir, who died by suicide in May. Her death, like many others, shook not just her family but reignited national concern about the mental health crisis simmering beneath Kota’s academic machinery.

These numbers are not isolated blips. They follow a grim pattern that has persisted for years. In 2023, the city recorded a staggering 26 student suicides — the highest ever in its history. The number dropped to 17 in 2024, prompting officials and institutions to tout a 50% decline and a sense of cautious optimism. Preventive measures were credited like emotional wellness programs, spring-loaded fans, and mentorship schemes.

But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story.

While statistical decline may suggest improvement on paper, the recurrence of suicides in 2025 makes one thing heartbreakingly clear: the core issues remain unaddressed. Each student who ends their life is not just a tragic exception. They are evidence of a deeper, structural dysfunction in Kota’s educational and emotional ecosystem.

Why, despite new safety nets, are students still choosing death over another day in a coaching class? What despair lies behind closed hostel doors? What words go unspoken in phone calls to home?

These deaths force us to confront uncomfortable truths, that the pressures are not only academic, but also emotional and existential. A drop in numbers cannot be celebrated when even one student feels that their only escape is to stop living. The data may fluctuate, but the distress remains constant.

So the question is not whether we’ve done enough to reduce the numbers. The question is — have we done enough to make these young lives feel valued beyond their ranks and results?

Until we can answer that with confidence, every statistic is not a success metric. It’s a warning sign. One that demands not just policy tweaks, but a fundamental reimagining of how we define success, support mental health, and protect our youth.

The Invisible Weight: Causes Behind the Crisis

The intense pressure to succeed is a significant factor contributing to the mental health crisis among students in Kota. Many students, often teenagers, are thrust into a highly competitive environment, away from the comfort of their homes. The fear of failure, coupled with the high stakes of entrance exams, creates a breeding ground for anxiety and depression.

Parental expectations further exacerbate the situation. Instances have been reported where parents, upon being informed about their child's deteriorating mental health, dismissed the concerns, urging them to "bear with it." Such attitudes highlight a lack of awareness and understanding of mental health issues. Let’s explore the underlying causes in greater depth.

1. The Crushing Burden of Expectations

From the moment students step into Kota, they enter a world where only ranks and results matter. Most are between 15 to 18 years old — an age meant for exploration and emotional growth, but here, they are treated like machines on a schedule. Parents invest lakhs of rupees, sometimes their life’s savings, believing success in NEET or IIT-JEE is the only acceptable outcome. This turns love into pressure, support into demand. Students begin to carry not just their own aspirations, but also their family’s pride, social status, and future livelihood, all on their fragile shoulders.

“My parents told me not to come back if I didn’t clear NEET.” - A real quote from a student’s suicide note (2023)

2. Isolation in the Crowd

Despite being surrounded by thousands of students, many find themselves terribly alone. Living far from home, many face homesickness and loneliness. There’s little to no emotional bonding, especially when peers are viewed as competitors, not friends. Conversations often revolve around scores and ranks, not feelings or fears. Over time, even the most resilient minds begin to falter under the silence of emotional neglect.

3. Coaching Culture: Factory of Fear

Many coaching institutes operate like academic factories. Students follow grueling timetables: waking up at 5 AM, attending back-to-back lectures, completing endless assignments, and writing weekly mock tests. There is barely time to breathe, let alone relax.

Failure in tests often results in public shaming or demotion to a lower batch — a humiliating blow to a student’s self-worth. Some are made to feel they are ‘wasting their parents’ money’ if they don’t perform well. The relentless competition creates a survival-of-the-fittest atmosphere, where only toppers are celebrated, and others feel invisible.

4. Mental Health: The Elephant in the Classroom

Mental health is still a taboo subject in many Indian households. When students begin to show signs of burnout, anxiety, or depression, they are often told to “be strong” or “focus harder.” There’s a dangerous glorification of suffering in silence. Many parents and institutions equate asking for help with weakness.

Though initiatives like counseling cells, helplines, and emotional wellness workshops exist, they’re often seen as tick-box measures. Students fear being labeled “weak” or “distracted” if they reach out.

Moreover, not all mental health professionals in Kota are adequately trained to deal with adolescent trauma or suicidal ideation. A crisis of this magnitude cannot be solved with token gestures, it demands systemic empathy.

A Crisis Met with Band-Aids: Measures Taken So Far

In response to the escalating mental health crisis, the Kota district administration and coaching institutes have rolled out a series of preventive measures. While these efforts signal a growing awareness of the problem, they often serve as surface-level solutions to a much deeper malaise.

1. Installation of Spring-Loaded Ceiling Fans:

One of the most visibly jarring measures taken in response to the suicide crisis in Kota has been the installation of spring-loaded ceiling fans in hostels. These mechanical devices are engineered to collapse under excessive weight, thereby physically preventing attempts to die by hanging. On the surface, it seems like a quick fix aimed at saving lives. And perhaps, in some cases, it has.

While this intervention may have physically prevented some suicides, it is, at best, a reactionary measure.It addresses the method, not the motive. The fan might break, but the despair, the hopelessness, and the silent suffering in a student’s heart remain unbroken. Moreover, it doesn't alleviate the stress, isolation, or fear that drives a student to consider such a step. Nor does it foster a culture of empathy, openness, or emotional support. It simply delays the tragedy, it doesn't prevent it.

It sends a disturbing message: that instead of transforming the pressure-cooker environment that breeds such despair, we are simply trying to mechanically block its most tragic expression.

What students truly need is not spring-loaded fans, but emotional safety nets. A support system that tells them it’s okay to fail, it’s okay to be afraid, and it’s more than okay to ask for help. Until that is put in place, even the most sophisticated devices cannot prevent what the system fails to heal from within.

It’s a grim reminder that the system is not solving the emotional distress, only attempting to restrict its tragic consequences.

2. No Detention, Just Delay:

Another well-meaning policy introduced in Kota's coaching ecosystem is the no-detention rule during the initial months of enrollment. The intention behind this move is clear: to ease students into the high-pressure environment and shield them from the immediate fear of being pushed into “lower-performing” batches — a practice that, in the past, carried with it a heavy emotional toll.

Traditionally, coaching institutes in Kota function like a tiered battlefield. Students are divided into batches based on performance in weekly or monthly tests, with top performers placed in elite groups, and others shuffled down the ladder. Being demoted was not just an academic shift, it was a psychological blow. For many students, it meant humiliation, shame, and a growing sense of failure. The no-detention policy seeks to postpone this harsh reality, giving students breathing room as they transition into a new academic and social environment.

However, this relief is often short-lived.

As the academic year progresses, the same rigid batch hierarchy resurfaces, and the competition intensifies. Students are once again evaluated and ranked constantly. The pressure to perform, to secure a spot in a “top batch” returns with even greater force.

In essence, the no-detention rule delays the pressure, but does not dismantle the system that causes it. It postpones the inevitable rather than addressing the root problem: the toxic culture of hyper-competition, where a student's worth is directly linked to their batch, rank, or test score.

Without a change in the value system that fuels this obsession with ranking and without robust emotional support structures in place, such policies risk becoming optical illusions of reform. What students truly need is not just more time before they fall, but a net that catches them when they do.

3. More Talk Than Therapy:

In a bid to uplift student morale and address the growing mental health crisis, many coaching institutes in Kota have introduced motivational sessions. These are often conducted by psychiatrists, bureaucrats, successful alumni, and ex-toppers — individuals who’ve “made it” and are seen as sources of inspiration. The intent is noble: to reassure students that they’re not alone, to instill hope, and to offer strategies for managing stress, failure, and expectations.

But while these sessions are well-intentioned, they often fall short of making a lasting impact, and in some cases, may do more harm than good.

The first issue lies in the lack of personalization. These are typically one-size-fits-all lectures delivered to hundreds of students at once. But students don’t come with identical experiences, personalities, or emotional resilience. What comforts one may trigger another. What motivates one may overwhelm someone else. Without an understanding of individual struggles like anxiety, homesickness, fear of failure, self-worth issues, these talks risk becoming generic and impersonal.

Second, there's often little to no follow-through. A one-time session may lift spirits temporarily, but without sustained engagement, its effect fades. Mental health support requires consistency, confidentiality, and trust, not just an hour-long pep talk once a semester. Students need safe spaces to talk, not just to listen.

Third, by framing well-being as something that can be fixed with motivational speeches or success stories, these sessions may unintentionally send the message that students should be able to “snap out of it” with willpower alone. This can deepen the stigma around seeking professional help and make students feel guilty or weak for continuing to struggle even after such sessions.

What truly makes a difference for students is not just inspiration, but access to licensed counselors, peer-support groups, and tailored psychological care. They need to hear not just stories of success, but also stories of struggle, vulnerability, and survival. They need to be reminded that it’s okay to not be okay, and more importantly, that help is not only available but encouraged. Until that happens, motivational sessions will remain just sessions, not solutions.

4. Rollout of the ‘Kota Cares’ program:

The launch of the ‘Kota Cares’ initiative was envisioned as a progressive step toward addressing the mental health crisis among coaching students. Designed to be a safe, judgment-free space, the platform aimed to encourage students to speak openly about their emotional struggles, share their fears, and seek support without shame.

On paper, it was a much-needed move. In a city where academic performance often overshadows personal well-being, such an initiative had the potential to humanize the student experience and break the silence surrounding mental health. However, the reality has been more complex.

Despite its noble intentions, ‘Kota Cares’ remains vastly underutilized. The core reason? Stigma.

Many students hesitate to reach out, fearing that acknowledging stress, anxiety, or depression will brand them as “weak,” “unstable,” or “not serious enough.” In a cutthroat environment where success is everything, and failure is viewed as personal inadequacy, even asking for help can feel like a risk. Students worry that if word gets out, they’ll be seen differently by peers, teachers, or even their own families.

The prevailing culture of silence around emotional vulnerability only makes matters worse. In Kota, strength is often equated with endurance, the ability to suppress, push through, and keep scoring high. Emotional expression, by contrast, is often seen as a distraction or indulgence. As a result, platforms like ‘Kota Cares’, while crucial, struggle to penetrate the deeper social and psychological barriers that discourage openness.

A support platform can only work when students trust it, not just to protect their privacy, but to truly understand and respond to their needs with empathy and care. To make ‘Kota Cares’ more than just a name, it must be woven into the daily culture of coaching life. Counselors should be introduced in orientations, mental health awareness should be normalized through storytelling and peer-led discussions, and emotional safety should be treated with the same importance as academic success.

Only then can students feel that sharing a struggle isn’t a sign of weakness, but a step toward strength.

Call for Policy Reforms: A Blueprint for Change

To truly address the root causes of student suicides in Kota and beyond, sweeping reforms are needed across multiple levels:

1. Mental Health Integration in Coaching & Curriculum

- Mandatory weekly counseling sessions in all coaching centers.

- Emotional wellness to be integrated into study schedules — not as an extra, but as a core component.

- Mental health screening at the time of admission and periodic follow-ups.

2. Parent-Student Counseling Before Admission

- Pre-admission orientation for parents and students on realistic expectations, coping strategies, and signs of burnout.

- Helplines and grievance redressal units for both parents and students.

3. Regulation of Coaching Institutes

- Government-monitored code of conduct to prevent academic harassment and emotional abuse.

- Limit on maximum study hours per day and mandatory recreation breaks.

- Penal provisions for institutes that encourage fear-based teaching methods or toxic competition.

4. Residential Welfare & Hostel Monitoring

- Regular inspection of hostel facilities for mental health infrastructure.

- Appoint trained resident counselors or mentors in hostels.

- Emergency distress buttons or apps that alert authorities in real-time.

Economic Implications: A City in Decline?

Kota has long been synonymous with India's booming coaching industry — a city that once thrived on the hopes and dreams of lakhs of aspiring students. But the recent surge in student suicides has not only triggered a humanitarian crisis, it has also cast a long, dark shadow over Kota’s economic stability.

The consequences are already visible. Student enrollment has plummeted by nearly 40%, dropping from over 2 lakh students to just around 1.2 lakh. This dramatic decline has hit the city's economy where it hurts the most in its lifeline: the education ecosystem.

Kota’s economy has been built around its identity as a coaching hub. Everything from housing and transportation to stationery, food, and healthcare orbits around the student population. With fewer students arriving each year, hostels and paying guest accommodations lie vacant, some for the first time in decades. Buildings that once had long waiting lists now carry faded "To Let" signs, dotting the streets like symbols of a declining empire.

Coaching centers, too, are feeling the squeeze. Reduced enrollments mean smaller batches, lower revenues, and in some cases, cutbacks on faculty or operations. Ancillary businesses such as cafés, libraries, printing shops, mess services, and tiffin providers, that depended on a steady influx of students are struggling to stay afloat.

The psychological toll of Kota’s reputation is starting to have economic consequences. Parents are increasingly reluctant to send their children to a city now associated more with pressure and tragedy than with success and opportunity. And with newer online platforms and regional coaching centers emerging as alternatives, Kota’s monopoly on academic excellence is weakening.

This shift isn’t just about numbers, it’s about trust. The very foundation of Kota’s economy was built on the belief that it could help students achieve their dreams. As that belief erodes, so too does the economic certainty of the city.

For a sustainable revival, Kota must go beyond damage control. It needs to reinvent itself not as a pressure cooker of achievement, but as a nurturing space for learning and growth. Because in the long run, a healthy student is not just a moral imperative, it’s an economic one too.

Because Every Life Matters.

Reforming Kota is not just about protecting students in one city. It’s about transforming the way we view education and success across India. Let this not be just another story that trends for a week and fades away.

Let us choose courage over complacency. Let us act, not after the next suicide, but now while we still can save those who feel they are drowning in silence.

Because no dream, no exam, and no expectation is worth a young life lost.

Rethinking Success: What Are We Teaching Our Children?

In our pursuit of creating engineers and doctors, are we forgetting to raise emotionally healthy, happy human beings? Should a teenager’s worth be measured solely by an exam rank?

It’s time we asked uncomfortable questions:

- Why are we forcing children to fit into a single mold of success?

- Why do parents treat Plan B as failure, and Plan A as the only acceptable dream?

- Why does the education system reward rote learning and ignore emotional intelligence?

Until we redefine success beyond a scorecard and treat well-being as a non-negotiable priority, Kota will continue to break under its own weight.

Conclusion: It’s Time to Choose Humanity Over Hustle

Kota is not just a city, it's a mirror reflecting the cracks in our education system, parenting models, and societal mindset. Behind every suicide statistic is a teenager who felt unseen, unheard, and unworthy, a child who needed empathy more than equations. Who needed someone to say, “It’s okay,” not, “You must.”

Let Kota not become the city where dreams go to die. Let it become a place where every student, regardless of their rank, feels seen, heard, and supported.

. . .

References:

- www.indiatimes.com

- www.indiatvnews.com

- www.moneycontrol.com

- www.indiatoday.com

- www.indianexpress.com

- www.theeconomictimes.com