In the historical record of India's judicial system, there emerge exceptional figures whose professional trajectories transcend the conventional parameters of their discipline. These are individuals who comprehend the law not merely as a compilation of statutes and jurisprudential precedents confined to judicial chambers, but rather as an instrument for societal transformation and the protection of human dignity for those systematised marginalised by institutional power structures. Justice K. Chandru of the Madras High Court is a classic example and inspiration for many law graduates in this category as a jurist who has deployed the law as an instrument of justice, essentially altering the circumstances of numerous individuals abandoned by conservative legal systems.

His professional journey him many respects brought contributions to many of contemporary India's legal and social developments. It encompasses the principled activism of a younger generation, the rigorous advocacy of legal practice, and ultimately, the consequential role of a judge who deliberately resisted the custodial function of merely continuing existing institutional arrangements. His professional trajectory reminds us that within the Indian legal apparatus, notwithstanding its documented institutional deficiencies and structural corruption, transformative possibilities exist when individuals of demonstrated ethical commitment occupy positions of judicial authority.

From Political Activism to Legal Advocacy: The Formation of a Constitutional Scholar

To comprehend his substantial contributions to human rights jurisprudence and constitutional justice, one must examine his professional evolution from political activism in Tamil Nadu to eventual elevation within the Madras High Court. This trajectory emerged not through inherited privilege or institutional patronage, but through sustained personal commitment to constitutional principles of equality and human dignity.

Born into a middle-class conventional family in Srirangam, Tiruchirappalli, his formative years were characterised by economic scarcity and familial disruption. Following his mother's death and the family's relocation to Chennai, young Chandru and his siblings experienced the material deprivations of post-independence India, awakening daily at four o'clock to obtain rationed food benefits. This experience of systemic deprivation catalysed his awareness of the fundamental structural inequalities organising Indian society.

During his undergraduate years at Loyola College in Chennai, he came under the intellectual influence of the Dravidian intellectual tradition and the radical political movements of the era. The Keezhvenmani massacre of 1968, in which forty-four Dalit agricultural workers were confined to a structure and burnt by landlords in a labour dispute, produced profound moral disturbance. He recalled subsequently: "This was really shocking. What crime did these innocent people commit?" This interrogation became the organising principle of his subsequent professional endeavours. He enrolled in the Communist Party of India (Marxist), motivated not by abstract ideological commitment alone, but by direct observation of working-class and marginalised community experiences.

This political engagement incurred institutional penalties. He was expelled from Loyola College in his second year for organising student demonstrations. Undeterred, he intensified his political participation, travelling throughout Tamil Nadu by public transport, addressing factory workers and agricultural labourers, and developing empirical knowledge of how subordinated populations steered institutional systems structured against their interests. He characterises this period as his "open university".

The inflexion point emerged during an official Commission of Inquiry examining the death of a university student, after police violence during the constitutional Emergency. A judicial officer, recognising his meticulous preparation and substantive advocacy, recommended legal education as an appropriate career trajectory. Thus, what commenced as a helpful decision was further continued by pursuing legal education, which led to providing room for him to continue political engagement, which later evolved into his principal professional commitment. The constitutional Emergency itself furnished an involuntary practical education, as he commenced drafting bail applications and acquiring operational understanding of legal institutional mechanisms.

The Practice of Law as Public Service: An Alternative Professional Model

Following legal qualification, he engaged with Row and Reddy, a law firm specialising in legal representation for economically disadvantaged populations. This constituted a deliberate professional choice grounded in his prior political formation. Throughout eight years of practice, he concentrated on cases involving industrial workers, economically disadvantaged persons, and communities systematically excluded from institutional justice. When the firm commenced accepting corporate clients, he terminated his association and established an independent practice.

Throughout his career as an advocate, Justice Chandru (Retd.) deliberately rejected the conventional professional pathway to financial accumulation. Numerous contemporaries were constructing substantial practices centred on corporate clientele and capital accumulation. He, by contrast, maintained a singular focus on cases involving workers, women, and members of systematically marginalised populations. He has articulated this orientation explicitly as, "Money was never a criterion. I had lived an entirely different lifestyle. My ambition was not to become a '5-star lawyer'."

His commitment extended beyond courtroom advocacy. He maintained participation in social mobilisation efforts while gradually reconceptualising his understanding of legal activism. He concluded that judicial boycotts were counterproductive. The courts, he determined, existed for litigants, specifically those economically and socially disadvantaged, those pursuing legal remedies, rather than for legal practitioners or judges concerned with institutional prestige. This philosophical evolution manifests in the film Jai Bhim, wherein the protagonist, during an active protest, overcomes police impediments to return to court for the case argument. This moment captures an essential truth regarding his professional transformation from external agitation to institutional legal defence; he demonstrated that judicial proceedings constitute an efficacious mechanism for justice advancement when deployed by attorneys of integrity.

The Raja Kannu Matter: Constitutional Protections Against State Violence

Among the numerous matters exemplifying his professional commitment, the case eventually dramatised in the film Jai Bhim demonstrates his legal and ethical strength. In 1993, Raja Kannu, a member of the Andai Kurumbar tribal community, was wrongly accused of jewel theft. Following police apprehension, he sustained torture during detention and subsequently expired. To escape institutional culpability, police personnel transported and disposed of his corpse in an adjacent jurisdiction, subsequently asserting that Kannu had escaped custody.

Kannu's widow, Parvathi, seeking to locate her deceased spouse, was approached by him. The subsequent litigation extended across thirteen years, demanding not merely legal acumen but also substantial personal strength. He submitted a habeas corpus petition to the Madras High Court. Police officers summoned by the tribunal dismissed Parvathi's testimony, contending that Kannu had simply absconded. At this critical stage, he invoked precedential authority, specifically the Rajan matter from Kerala involving a missing engineering student, by presenting this jurisprudence to the court.

The litigation's trajectory shifted substantially when a reconstituted bench comprising Justices Mishra and Patil assumed jurisdiction. He recognised that Justice Mishra possessed established jurisprudence regarding police violence, having convicted police personnel in precursor matters. The justices communicated to the advocate general their inability to credit the police account. Through his persistent advocacy, institutional facts eventually emerged that Kannu had indeed expired during police detention, having been murdered by police personnel.

The conflict intensified considerably when police officials offered monetary inducements to both Parvathi and Chandru. He responded without hesitation, physically expelling the financial inducements and the police officers from his office. Following thirteen years of litigation, the tribunal finally adjudicated that this constituted a custodial death, sentencing the responsible police officials to fourteen years' rigorous imprisonment.

This matter represents substantially more than a legal victory. It embodies the principle that constitutional law, when exercised by practitioners of unquestionable integrity, can offer protective mechanisms for the most vulnerable institutional populations against state violence. It demonstrates that justice pursuit, though necessarily long-drawn-out and contested by entrenched institutional interests committed to concealment, remains institutionally achievable.

Judicial Elevation: The Exercise of Constitutional Judicial Authority

When Justice Chandru obtained appointment as an Additional Judge of the Madras High Court in 2006, professional observers noted the apparent contradiction. He had been characterised as a "terrorist lawyer" by then-Chief Minister Jayalalithaa for his defence of political detainees and activists. Yet the judicial institution, acknowledging demonstrated exceptional capability, ultimately elevated him to the bench.

His judicial performance established remarkable metrics. Across six and a half years, he disposed of ninety-six thousand matters, which is a quantitative measure reflecting both his personal dedication and meticulous organisational systems. He administered an average of seventy-five matters daily, refusing to consume judicial time with procedural administration while substantial justice remained outstanding. Where numerous judges devoted the initial quarter of judicial hours to administrative proceedings, Justice Chandru completed such proceedings between 10:15 and 10:30, subsequently directing comprehensive attention to substantive matters.

His judicial distinction derived not principally from statistical productivity but from judgment quality and professional conduct. He requested that attorneys not employ the honorific "My Lord," regarding such formality as hierarchically reinforcing and substantively irrelevant. He declined a staff bearer to announce his arrival, viewing such ceremonial practice as theatrically unnecessary. When offered Personal Security, he declined, characterising such arrangements as "more of a status symbol rather than being based on any actual threat perception." The judiciary then deployed approximately 240 security personnel across 60 judges on rotating assignment, plus 60 supplementary Personal Security Officers, for a total numbering 300. His argument possessed inescapable logic that such resources could adequately defend metropolitan areas.

Upon judicial retirement in 2013, subsequent to submitting asset declarations to the Chief Justice, returning his official vehicle key, and declining ceremonial departure proceedings, he departed by local transport. This limited exit and communicated substantive meaning that he maintained that judicial dignity derived not from ceremonial observance and institutional display, but from principled decision-making and societal service.

Constitutional Framework: Jurisprudential Vision and Institutional Philosophy

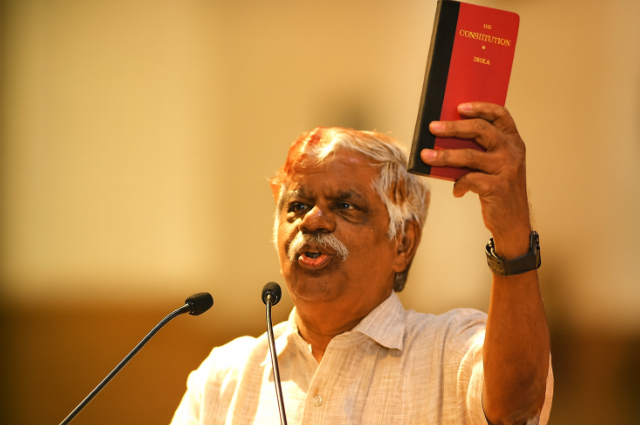

His determinations collectively articulate a clear constitutional understanding. He has composed an extensive exposition regarding constitutional significance, particularly concerning Dr Ambedkar's constitutional vision. For him, the constitutional document constitutes substantially more than a technical legal provision; it represents a political commitment to equality, human dignity, and the subordination system.

Addressing the political consciousness question in legal practice, he has articulated a philosophy diverging from prevailing professional convention. He maintains that constitutional legal study necessarily entails engagement with a political document acknowledged by primary political constituencies during constitutional foundation. His student activist experience and subsequent legal practice experience facilitated societal comprehension that, functioning as a judge, enabled the resolution of complex matters originating in societal contradictions.

He additionally addresses the demanding question of caste-classified political parties, observing that constitutional frameworks do not ban their existence, yet their institutional actions inevitably manifest caste character. He notes that even major political organisations operate according to caste interests within their operational territories. This solid institutional analysis reflects his commitment to societal truth articulation.

Broader Professional Influence: The Jai Bhim Phenomenon

The cinematographic dramatisation of his professional narrative in Jai Bhim represents a distinctive moment wherein cinema has captured an authentic human exemplar—not a superheroic figure, but an individual of extraordinary ethical commitment who deployed available institutional mechanisms to advance justice. Director TJ Gnanavel, functioning previously as a journalist, had composed substantial analysis regarding his determinations and maintained long-standing professional admiration.

This constitutes his authentic institutional influence that is not quantified through case disposition numbers or counted judgments, though these retain significance, but is measured through motivation provided to others, expecting whether professional capabilities might receive deployment in service of institutionally disadvantaged and vulnerable populations.

Constitutional Commitment and Legal Professional Responsibility

Reflecting upon Justice Chandru's professional history as a lawyer, I am aware that the legal profession, at its best institutional function, excels in simple technical rule manipulation for compensated clients. Legal practitioners are the officers of the court bearing institutional responsibility for justice maintenance and rule-of-law advancement. The constitutional framework to which practitioners take oath excels abstract documentary status; it constitutes a substantive commitment to human dignity and constitutional equality.

Minority communities, including Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, advance materially only when governmental and societal institutions function consistently with the constitutional letter and spirit. This requirement surpasses statutory enactment and judicial determination; it necessitates social consciousness transformation and political implementation commitment. Justice Chandru has demonstrated that although the judiciary confronts substantive institutional restrictions, it possesses remarkable transformative potential when occupied by individuals committed to legal values and justice advancement.

His post-retirement period has maintained a commitment to community service, composition of legal and social analysis, instruction in legal institutions, judicial academies, and response to ordinary citizen legal inquiries. He maintains that work undertaken during judicial service continues as his ongoing institutional commitment, reflecting his understanding that justice is beyond the courtroom confinement and extends across all social institutional dimensions.

Justice Chandru's professional trajectory simultaneously represents institutional accomplishment. In a profession characteristically marked by ethical compromise, financial acquisition, and power exercise, he has pursued an alternative trajectory. He has established that law practice with uncompromised integrity remains achievable, that judicial elevation need not produce institutional corruption, and that professional capabilities can advance justice and human rights.

For emerging legal practitioners and prospective judges in India, his professional example presents a simultaneous challenge and possibility. The challenge demands institutional examination of whether work serves power or disadvantaged populations, whether professional practice advances justice or participates in injustice. The possibility invites reconceptualisation that law and legal practitioners might function constitutionally by advancing justice, economic and social, as well as procedural.

As India continues confronting justice, equality, and rights questions, his professional history and constitutional jurisprudence maintain profound contemporary significance. His determinations continue functioning as judicial authority; his analytical writings continue guiding those seeking constitutional justice comprehension; and his professional example continues inspiring those maintaining faith that constitutional law can function as an instrument protecting vulnerable institutional populations against state violence and systemic deprivation.

Lastly, Justice his journey reminds us that the role of a judge is not confined to merely hearing the arguments of the plaintiff and the defendant. It extends further to the application and interpretation of the law. Moreover, one must remember that justice is not only about being done but also about being seen to be done. The public must be able to perceive, on the face of it, that the judgment pronounced upholds the principles of natural justice. Only when justice is both delivered and visibly affirmed in the courtroom can a judge be said to have truly fulfilled his duty.

References:

- https://thebetterindia.com

- https://www.theweek.in

- https://provokelifestyle.in

- https://www.thehindu.com

- https://www.thenewsminute.com