Without highlighting the contributions of women, the history of the Indian struggle would be incomplete. The sacrifice made by the women of India shall take precedence. They suffered numerous tortures, exploitations, and sufferings to achieve their freedom, and they did it with true spirit and undaunted courage. When the majority of the men's freedom fighters were imprisoned, the women stepped forward to lead the fight. The list of remarkable women whose names have gone down in history for their unwavering dedication to India's service is long.

What follows is a brief exploration of a woman's difficult feminism as she lived at the crossroads of two cultures: her native Hyderabad and British India's colonial culture. She transitioned from the former's diction and demeanor to poetry and politics forged, at least in her later years, during Nationalist politics' turmoil. However, there remain certain unanswered issues about her life and writings. There appears to be a profound chasm between her poetry's passionate though confining feelings and the political life she advocated. Sarojini Naidu began writing when she was twelve years old. Arthur Symons published her first collection of poems, The Golden Threshold. She had a successful literary career as a result of her cerebral management of the English language. In 1914, her works The Golden Threshold (1905) and The Bird of Time (1912) earned her membership in the Royal Society of Literature. The Scepter Flute (1928), The Feather of Dawn (1961), Feast of Youth, The Wizard Mask, and A Treasury of Poems are some of the alternative titles for a collection of poems. Mahashree Arvind, Rabindranath Tagore, and Jawaharlal Nehru praised her English writings with Indian souls.

Introduction

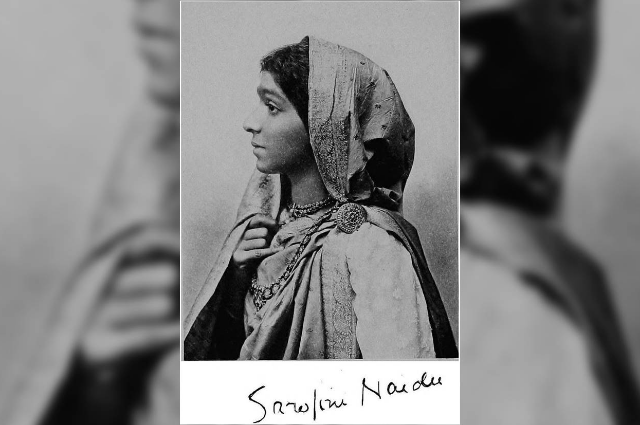

Sarojini Naidu (Bengali:), often known as The Nightingale of India, was a child prodigy, Indian freedom activist, and poet who was born as Sarojini Chattopadhyay (Bengali:). From 1947 until 1949, Naidu served as the first governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, making her the first woman to lead an Indian state. In 1925, she became the second woman and the first Indian woman to be elected president of the Indian National Congress.

Research questions:

- What was the political struggle of Sarojini Naidu in the national movement of India?

- What was the role played by Sarojini Naidu when she became the president of the congress party?

- What was the role of Sarojini Naidu in the salt march which helped in the freedom struggle?

Early Life

Sarojini Naidu was born on February 13, 1879, in Hyderabad, to Aghore Nath Chattopadhyay and Barada Sundari Debi. Her father moved to Hyderabad after receiving a degree in science from Edinburgh University, where he founded and ran the Hyderabad College, which eventually became the Nizam's College in Hyderabad. Her mother was a poetess, and she used to write Bengali poetry. Among the eight siblings, she was the oldest. Virendranath Chattopadhyaya was a revolutionary, whereas Harindranath Chattopadhyaya was a poet, dramatist, and actor.

Naidu graduated from the University of Madras with a matriculation degree but took a four-year sabbatical from her studies. The “Nizam scholarship Trust,” established by the 6th Nizam - Mir Mahbub Ali Khan in 1895, provided her with the opportunity to study in England, first at King's College London and then at Girton College, Cambridge. Naidu met Govindarajulu Naidu, a doctor by profession, and married him at the age of 19, after completing her schooling. Inter-caste marriages were not permitted at the time, but her father sanctioned the union. They had five children together. Padmaja, her daughter, was elected Governor of West Bengal.

The Golden Threshold

The Golden Threshold is a University of Hyderabad off-campus extension. Naidu's father Aghornath Chattopadhyay, the first Principal of Hyderabad College, lived in the building. It was named after Naidu's poetry collection. The University of Hyderabad's Sarojini Naidu School of Arts and Communication is now housed in Golden Threshold. It was the epicenter of numerous reformist ideals in Hyderabad during the Chattopadhyay family's tenure, spanning from marriage, education, women's empowerment, literature, and nationalism.

Political career and her contributions

Following the partition of Bengal in 1905, Naidu joined the Indian national movement. Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Rabindranath Tagore, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Annie Besant, C. P. Ramaswami Iyer, Mahatma Gandhi, and Jawaharlal Nehru were among the people she met. She traveled around India from 1915 to 1918, giving lectures on social welfare, women's empowerment, and nationalism. In 1917, she also assisted in the formation of the Women's Indian Association (WIA). She was sent to London with Annie Besant, the President of the Women's International Association, to argue the case for the women's vote to the Joint Select Committee.

President of the Congress party

In 1925, Naidu officiated the Indian National Congress's annual session in Cawnpore (now Kanpur). She presided over the East African Indian Congress in South Africa in 1929. The British government honored her with the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for her efforts during the Indian plague epidemic. She attended the Round Table Conference with Gandhi and Madan Mohan Malaviya in 1931. She was imprisoned alongside Gandhi and other leaders for her role in the Civil Disobedience Movement. During the "Quit India" agitation in 1942, she was detained.

Her initial conversation with Gandhi defined the standard for the rest of her political career. After the success of his satyagraha protest against the British imposition of taxes on Indians, and against the statute requiring all Indians to be fingerprinted and carry passes, Gandhi arrived in London in 1914. He is summoned by Naidu.

Naidu's political career would be defined by his meticulous attention to detail and refusal to glorify, both of which were revealed in this brief interaction. She was heavily active in Gandhi's Salt March in 1930, five years after she was elected President of the Indian National Congress. Gandhi and his group walked down to the sea to bathe at the crack of dawn on April 6, 1930; he then collected a few bits of salt that had collected on the beach in his palm.

Role in the salt march

Thousands of people accompanied Gandhi in symbolic opposition to the British salt law, which gave them a monopoly on the manufacturing of salt. Thousands of women took part, carrying earthenware and metal pots to carry away salt water. Once the salt had cured, it was auctioned off in front of a large crowd, demonstrating how nature might be used to aid in the fight for national independence. Gandhi was arrested on May 5th, and Sarojini Naidu took over as the leader of the non-violent movement.

She headed Darshana with 25,000 people, prepared to operate the salt works there as Gandhi had intended. The weather was hot and dry, and the volunteers were parched. The cops were dispatched to meet them and savagely beat them, often over the head. Naidu was unflappable. She spoke to the volunteers, prayed with them, and sat in a small deckchair writing or spinning khadi to keep her strength up. Naidu sat calmly, maintaining watch while the Gandhian volunteers who had courted arrest succumbed to police blows. She was arrested and taken to jail by the middle of the month.

She was imprisoned several times, the most recent and tragic being in 1942, following the Quit India Resolution, when she was held in the Aga Khan palace with Gandhi and his wife Kasturba. They were all afflicted by illness and inactivity. Gandhi began a death-defying fast in February of the following year, while still imprisoned. When Kasturba, who had been suffering from a slow, extended sickness, died, it was a sad blow; following her death, Gandhi was released. Naidu, who had contracted malaria, was set free on March 21, 1943, at the age of 64.

Despite her political popularity, Sarojini Naidu originally rose to attention as a poet, and she was lauded for it. Her images of private, pained women experiencing emotional deprivation, even psychological captivity, stand as a sharp contrast to the public life she so courageously pursued. From as early as 1903, she went endless kilometers in the cause of national freedom, often in hardship and risking incarceration, campaigning in her powerful orator's voice all over India.

Was she able to use her poetry to cauterize her grief and then move outside into the public sphere? Or did the poems, with their occasionally cloying diction and female figures locked in unredeemed sexuality, push her to abandon them, the writer herself becoming increasingly obsessed by the political battle until she effectively stopped writing in 1917? Naidu inherited some of India's complicated linguistic circumstances. She was born in the city of Hyderabad in 1879 to Bengali parents and spoke Urdu, the Islamic language of culture in Hyderabad. Living on the border of Bengali and Urdu, Naidu added English, the colonial language, to the mix. She wrote poetry and delivered impressive orations in English.

Brief analysis and key takeaways from Sarojini Naidu's contribution

She showed to be a trustworthy lieutenant. She calmed the rotors, sold forbidden books, and spoke at frantic gatherings on the slaughter at Jallianwala Bag in Amritsar with remarkable bravery. When Mahatma Gandhi appointed her to lead the salt Satyagraha in 1930, legends of her bravery abound. After Gandhi's incarceration, she organized 2,000 volunteers to storm the Dahrsana Salt Works under the sweltering sun, while the police stood half a mile away with rifles and lathis (steel-tipped clubs).

Conclusion

Sarojini Naidu died of a heart attack on March 2, 1949, while working at her Lucknow office. Sarojini Naidu College for Women, Sarojini Naidu Medical College, Sarojini Devi Eye Hospital, and the University of Hyderabad's Sarojini Naidu School of Arts and Communication are among the institutions named after her. “While in Bombay, we had the good fortune to meet Mrs. Sarojini Naidu, the recently elected President of the All-India Congress and a woman,” Aldous Huxley wrote. Who blends enormous intellectual power with an appeal, tenderness with daring vigor, a broad culture with creativity, and earnestness with humor in a surprising way.

References

- Jungalwalla, P.N. Indian Literature, vol. 9, no. 2, 1966, pp. 101–103. JSTOR

- Sinha, Mrinalini. “Refashioning Mother India: Feminism and Nationalism in Late-Colonial India.” Feminist Studies, vol. 26, no. 3, 2000, pp. 623–644. JSTOR.

- Devi, D. Syamala. “THE CONTRIBUTION OF WOMEN PARLIAMENTARIANS IN INDIA.” The Indian Journal of Political Science, vol. 55, no. 4, 1994, pp. 411–416. JSTOR.

- Chatterjee, Manini. “1930: Turning Point in the Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle.” Social Scientist, vol. 29, no. 7/8, 2001, pp. 39–47. JSTOR.

- “East Is East: Where Postcolonialism Is Neo-Orientalist – the Cases of Sarojini Naidu and Arundhati Roy.” Stories of Women: Gender and Narrative in the Postcolonial Nation, by ELLEKE BOEHMER, Manchester University Press, Manchester; New York, 2005, pp. 158–171. JSTOR.

- Jones, Diane M. “Nationalism and Women's Liberation: The Cases of India and China.” The History Teacher, vol. 29, no. 2, 1996, pp. 145–154. JSTOR.

- Das, Taraknath. “The Progress of the Non-Violent Revolution in India.” The Journal of International Relations, vol. 12, no. 2, 1921, pp. 204–214. JSTOR.

- Dwivedi, A. N. “Sarojini—The Poet (Born February 13, 1879).” Indian Literature, vol. 22, no. 3, 1979, pp. 115–126. JSTOR.

- Imam, Hassan. “MAHATMA GANDHI IN POPULAR IMAGINATION: A STUDY OF LITERATURE OF THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 74, 2013, pp. 571–580.

- Eunice de Souza. “Recovering a Tradition: Forgotten Women's Voices.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 41, no. 17, 2006, pp. 1642–1645. JSTOR