"The only serious utopia is a negative utopia – and even that is conceivable only if one offers the most unsparingly precise – hyperbolic, if you wish – analysis of the state of affairs." - Michael Haneke

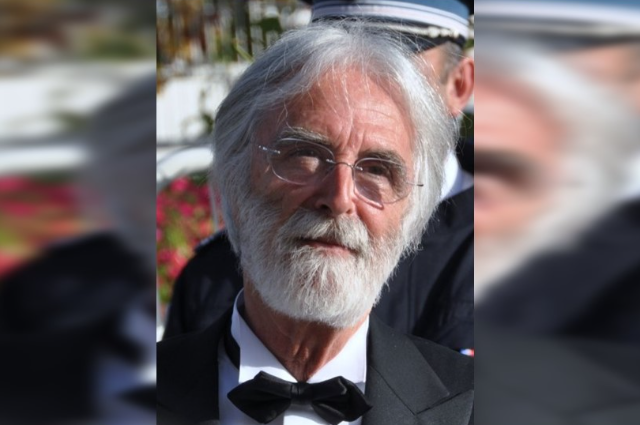

In 1989, during the release of The Seventh Continent, the audience got repulsed, particularly in two scenes – the breaking of the aquarium and flushing the money down the toilet. With this kind of reaction, the director Michael Haneke remarked that in contemporary society, the idea of destroying money is more taboo than parents killing their own child and themselves. In every regard, these images (breaking the aquarium or flushing the money down the toilet and many more) come from a 'negative utopia,' a state filled with gloom under the façade of a ‘utopic’ perfection. For Haneke, 'utopia' is a naïve concept, precisely for people of the West, as Westerners know exactly how things stand in society in its full potential. They have all the necessary knowledge, and there is nothing to gain anymore. The only thing they can do is to articulate that knowledge. For Haneke, that is the highest level of modernity one can reach while living in Western countries. So, as a Westerner, he can't be utopic. Rather, in the form of 'negative utopia,' which is filled with 'dread and destruction,' he can go far enough to prompt resistance against this fallacy of 'utopian modernity.'

This resistance has to be addressed properly when we study the filmic texts of Michael Haneke. It is rather difficult as he doesn't allow the viewers to engage as passive consumers of images by creating an invisible barrier between them and the film itself, providing minimal on-screen information and questioning the ethical standpoint of that information projected on the screen. Oftentimes scenes in his films (or the film as a whole) begin or end in medias res, creating a fragmentary narrative. Also, he blurs the line between reality and the projection of reality. With this very nature of his filmic language, he tries to pose the question of the ethics of the projected images and our perception of them. As a result, oftentimes the regular viewers (or critics) of Haneke's films get offended or get too overwhelmed by the ethical questions (for example, British film critic Mark Kermode’s outrageous headline to his Observer review of Haneke's US remake of Funny Games (2007): 'scare us, repulse us, just don't lecture us').

This may be a problem with the audience, especially from the West, who are widely passive consumers of images exposed to Hollywood standards of filmmaking. Those images are ‘utopic’ in nature, so they tend to resolve the most unresolvable situations. But the images coming from a 'negative utopia' pose questions about the very nature of this resolution. They do not reduce the philosophical nature of the images by giving away everything on the face of the viewer; rather, they consist of ambiguity. And, this ambiguous nature of images constantly gives rise to the questions that we as viewers should ask ourselves while watching a movie. This whole agenda of questioning (or we can use the word 'interrogating') in Haneke's filmic language often comes as the critique of the whole idea of ‘Western modernity’, which claims to be a superior sociopolitical decree than the rest of the world. By questioning, he tries to find the fault lines in this very situation. And perhaps for any Westerner like him, this is the only ethical way to have a resolution in their unresolvable tales.

In this article, I try to address and articulate the philosophical questions Haneke systematically poses with his films. But rather than having a literal answer to these questions, I can only pose more questions - to us, the viewers; to Haneke or the characters of his films. And, perhaps, that is the most appropriate way to experience his works.

The 'Glaciation of Feelings' in the 'Trilogy':

After a decade of working on Austrian television, Michael Haneke makes his feature film debut with 1989's The Seventh Continent. The film chronicles the last three years of an Austrian bourgeois family caught in their mundane daily routines before their ritualistic suicide. In a disturbing study of bourgeois space and alienation in modern society, Haneke deals with the philosophical questions of existence in a consumerist world. He takes these questions further in his next two films, Benny's Video (1992) and 71 Fragments of the Chronology of Chance (1994), and constructs a trilogy. According to Haneke, these three films constitute upon reports on the progressive emotional glaciation of his country (The Seventh Continent is based on a real-life event Haneke read in the newspaper. So, the event of a senseless shooting in the Viennese bank in the climax of 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance).

It is not so difficult to think that these events are saddening for a conscious filmmaker like Haneke. And thus, he tries to examine the roots of this 'glaciation of feelings' around him. Although the stories come from Austria, they are universal for everywhere, having the same privileges and order. Thus, to find the roots of this 'glaciation,' we need to read them against the contemporary social and cultural theory and the anxieties that these theorists addressed. In the 1980s and 1990s, Marc Augé, Jean Baudrillard, Gilles Deleuze, and others were scrutinizing the very perceptual systems (and the environment and conditions fostering them) that Haneke takes to task in his 'Trilogy.'

If we start this discussion with Marc Augé's idea of 'supermodernity' or 'hypermodernity', we can find a unique and useful reference point for Haneke's stark dramaturgy in his earlier three films. Augé investigates what form of obligation we encounter in the anonymous ‘non-places’ of modern urban space: hotel rooms, supermarkets, ATM machines, and other transit points at which we spend an increasing proportion of our lives. Non-places refer to spaces "which cannot be defined as relational, historical, or concerned with identity." Augé argues that although we don't ‘rest’ or ‘reside’ in non-places but merely pass through, we nevertheless enjoy a contractual relationship with the world. These ‘contracts’ are symbolized in train or plane tickets, bank cards, and email addresses. And from such places, a paradoxical condition emerges that Augé named the 'supermodernity' or 'hypermodernity.'

This paradox, on the one hand, implies a proliferation of events, a surfeit of history, and above all an abundance of news and information describing these occurrences. At the same time, this excess means that "there is no room for history unless it has been transformed into an element of spectacle, usually in allusive texts. What reigns there is actuality, the urgency of the present moment." Supermodernity generates a paradoxical excess and lack of identity. PIN codes, email addresses, Social Security cards, driver's licenses, and national identity cards with biometric data function to differentiate between individuals. At the same time, this proliferation has made personal identity more rigid and formally interchangeable: everyone can be identified by a "number," and one's identity can be "stolen."

This is the diegetic world of The Seventh Continent: supermarket checkout counters and credit cards, car washes and automatic garage doors; as Amos Vogel describes the film, "anonymity, coldness, alienation amidst a surfeit of commodities and comfort." The characters wander aimlessly and seemingly without motivation between Augé's anonymous transit points and temporary abodes: the home, that traditional point of bourgeois differentiation, is a refuge but also a prison; it is one of many in the suburban development. The family could be anywhere, on any seventh continent, most important (and most alienating and destructive) is the dialectic between anonymity and identity.

This is also a vital point in studying the character of Benny in Benny's Video. Like the characters in The Seventh Continent, Benny dwells in 'supermodernity.' He wanders in the streets aimlessly, and his work seemingly has no motivation. He might be a regular at McDonald's and the video store, but this hardly means the employees there know his name. Haneke telegraphs these interactions in close-ups (which he uses also in The Seventh Continent and other films in his oeuvre) of hands, money, cash register LED panels, hand-stamp club 'tickets,' and video identification numbers. These are contractual transactions rather than personal encounters. When Benny and his acquaintance discuss the upcoming AC/DC concert, they are less concerned with the music; getting the ticket is most important for them

But in the context of 'glaciation of feelings,' the dialectic between anonymity and identity dwells at the personal level. But what about the interpersonal relationship in this context of 'glaciation'? In works such as "Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia," Gilles Deleuze diagnoses the contemporary age as one in which emotions are dulled, communication dissolves, and relationships are eroding and losing connectivity. This dissolution of communal, sexual, and image relations occurs, in Peter Canning's lucid summary of Deleuze, "because relations (sexual, social, affective, episto-phenomological) mediated by the signifier that keeps us unconscious of their erotic-aggressive condition have broken down, and only money power differentials link one 'character' to another, one movement or gesture to another, in a chain of erotic aggressive attitudes. Money, the diffuse conspiracy of capital, the immanent symptom of our 'universal schizophrenia.'"

If we agree with this hypothesis, then the symptoms of this ‘universal schizophrenia’ are surely legible for Benny (Benny's Video); Georg, Anna, and Evi (The Seventh Continent); and Maximilian B (71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance). These characters have no friends, and most of their acquaintances are anonymous. Even their interactions with their close ones are determined by capitalist objects. Benny's parents communicate with him through notes and bills. The family in The Seventh Continent lacks face-to-face interactions with each other in their banal routinized life of capitalist conformity, and the objects signifying this become the only medium for communication. Also, in 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, the characters try to communicate through different games or video screens – another device of capitalism. These communications desensitize humanity (i.e., Benny does not attempt to speak to his father, who must interrogate to ascertain a sketch of the murder of the girl), and oftentimes what they mean gets lost in translation. Thus, the characters' interpersonal relationships become 'glacial,' and for them, the last remaining absolute capital and option for communication is violence. For Haneke, this violence is a chance act where the characters at least get to communicate without desensitizing their humanity.

Spectatorship and Violence:

Though this violence is a chance act for the characters, they can't be labeled as something cathartic. In Haneke's films, violent acts are perhaps the only ethical acts the characters can commit. But rather than creating a catharsis through this, he poses the very nature of the violence as an ethical question of spectatorship to us. As I mentioned earlier, Haneke's filmic images come from a 'negative utopia,' where the ethical questioning about the very nature of the image projected on the screen is a key factor. With the violent imagery, Haneke tries to ask us, 'What is your ethical standpoint against the consumption of these images?' Speaking about this, he once said in an interview, "We are all aware that we are consumers of violence. No one is so stupid when watching a film. When watching a violent film, he wants to consume violence. It is not a matter of knowing this. It's a matter of having the viewer perceive what it is he usually consumes."

To understand this further, we should look into his fourth feature, Funny Games (1997). Although the ethical question of the consumption of violence is showcased in his 'Trilogy' with the newsreel footage of various atrocities across the world in 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994) or the video of pig slaughtering in Benny's Video (1992), Funny Games (both the original and remake) is perhaps the only film in Haneke's oeuvre where he tries to overtly deal with the situation. Maybe for this reason, critics like Mark Kermode get offended and accuse the film of being too academic and becoming a moral lecture.

Funny Games tells the story of a bourgeois family murdered by two young sociopaths while on holiday, and it is employed as a device to interrogate the sometimes-pleasurable viewing of images of other people's suffering. In every aspect, Funny Games is a deconstruction of the formulaic family-taken-hostage scenario common to any Hollywood horror and thriller film (thus Haneke initially intended to make the film for the American audience, which he later fulfilled by remaking his original Austrian film). But it also emphasizes the spectator's responsibility to examine the appeal of watching others in pain. To do so, Haneke takes a unique technique. One of the two sociopaths, Paul, often breaks the fourth wall, informing us that he is aware of our presence behind the screen. Drawing upon the philosophy of ethics and the face by Emmanuel Levinas, it suggests that this direct address can engage the viewer's sense of responsibility in ways that other cinematic images of faces may not. The face-to-face relation between spectators and Paul explicitly prompts reflection on the ethical dimensions of the narrative and, more broadly, of film violence and spectatorship.

Viewers have become fascinated with the screen as a medium that can communicate suffering. Because "looking at horrible situations is so fascinating because the spectator is not directly concerned". Thus, images of fictitious and actual pain are turned into a spectacle: dramatized torture scenes in the cinema; slow-motion replays of sporting injuries on television; beheadings and executions of prisoners on the internet. But why would we look at the image of horror or pain? Susan Sontag argues in her essay "Regarding the Pain of Others" that we have 'the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching,' as well as 'the pleasure of flinching'. But when someone sees us looking at pain and doing nothing about it, we feel ashamed. In his essay, "The Ethical Screen: Funny Games and the Spectacle of Pain," Alex Gerbaz writes, "When somebody turns to face us (either the person in pain or a third party), catches us in the act of looking, our morality comes into question. This 'face-to-face' moment exposes our voyeurism and provokes us in a way that is similar to an image of cruelty, asking: 'How can you look at this?'"

If we go back again to the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas, it implies that to be responsible starts with not only seeing another person's face but also showing one's face. He claims that 'the Other faces me and puts me in question' – this face-to-face encounter 'tears consciousness up from its center, submitting it to the Other.' A disruption of consciousness here means opening up to personal and social responsibility, the Other being that which lies outside of our conscious experience yet to which we are ethically related. So, by seeing the face of the other, we can see our own face. This is the ethical standpoint Haneke wants us to be aware of with Funny Games – to question our ethics while watching violent imagery on screen.

Simulation and Control over Reality:

One of the key themes of Michael Haneke's films is the relationship between reality and the representation of that reality. Oftentimes, his films consist of images on TV, mobile, laptop screens, photographs (e.g., Code Unknown, 2000; Happy End, 2017) or even images captured on home video cameras (Benny’s Video, 1992). Sometimes, he even goes further where the line between reality and its representation becomes obscured (Cache, 2005). In every Haneke film, the characters belong to a capitalist culture, where the only way for them to continue living is by consuming. So, by using these techniques, Haneke tries to examine the characters' sense of identifying the real and its representation through the rapid consumption of media images.

On that note, if we look into the French cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard's theory of simulation, it announces the death of representation: 'All of the Western faith and good faith was engaged in this wager on representation: that a sign could refer to the depth of meaning, that a sign could exchange for meaning, and that something could guarantee this exchange'. According to Baudrillard, this wager has been irrevocably lost: our situation today is simulation, and signs have become pure simulacra. In simulation, "The real is produced from miniaturized units, from matrices, memory banks, and command models – and with these, it can be reproduced an indefinite number of times. It no longer has to be rational, since it is no longer measured against some ideal or negative instance. It is nothing more than operational. Since it is no longer enveloped by an imaginary, it is no longer real at all. It is hyperreal, the producer of an irradiating synthesis of combinatory models in a hyperspace without atmosphere." The loss of the distinction between original and copy in the age of digital media disturbs Baudrillard. This loss, according to him, also signals the end of rationality: the 'Abbid (copy)' now needs no 'Urbid (prototype)'. Thus, for Baudrillard, to simulate is not just to fake or feign something but to make something more real than real. Because of the process and logic of simulation, according to Baudrillard, it becomes increasingly difficult or impossible to distinguish between true and false.

Haneke subscribes to this vision of the world. He states in an interview, “Through the permanent falsifying of the world in the media, leading us only to perceive the world in terms of images, a dangerous situation is being created…a Coca-Cola advertisement takes on the same level of reality as news footage.” Thus, Benny (Benny's Video), a video freak, is accustomed to experiencing life through a viewfinder. His room is dim, with shades permanently drawn, while his video camera gazes onto the street and transmits the signal to a monitor. Or, Eve (Happy End) watches the dreadful scenes of her mother's passing out by poisoning or her grandfather's attempted suicide on her phone screen. For them, the actual and virtual are indistinguishable. And, the experience of virtual reality is even more dramatic than the actual incident itself – it is more important and somehow more real for them.

In this context, I would like to argue here that these actions give the characters control over reality. Benny's essential element of control is to 'rewind.' The pig's death or his murder of the girl can be reviewed an indefinite number of times, undone, prolonged, and abstracted in slow motion. He has control over reality. Similarly, Eve or Georges (Code Unknown), snaps voyeuristically the real faces of people in the Paris metro – just to gain control over their emotions behind the faces.

But the characters are not the only persons who enjoy this control. As a director, Haneke enjoys it himself also. The prime example of this directorial control should be the rewinding scene in Funny Games (1997 and 2007) or the anonymous tapes in Cache. By doing this, he places himself in the same contention as his characters and tries to study the ethical standpoint of a filmmaker.

The Role of Virtual Image in Desire and Fantasy:

If we extrapolate this idea of virtual images beyond simulation and control, we can find an interesting aspect of desire and fantasy related to virtual images.

Studying further the character of Benny (Benny's Video, 1992), we can find that he harbors a 'desire' for some experimental sense of the real. Thus, when asked about the reason for the murder of the nameless girl by his father, he blatantly answers that he wants 'to see how it is'. Baudrillard addresses this nostalgia for the real. In our age, a paradoxical fixation on authenticity has developed, an 'escalation of the true, of the lived experience…a panic-stricken production of the real and the referential.' This fascination with lived experience constitutes, however, a symptom of its loss. Benny hardly seeks a modernist form of authenticity. His desire for the real is, in fact, already a mediated version, which he betrays in his formulation that he wants to 'see' how it is. Benny 'desires' to kill, but more importantly, he 'desires' to see himself on his monitor killing and to be able to rewind, slow down, and edit the act on his console.

Similarly, the role of virtual images largely influences the dimension of 'fantasy.' With the consumption of video images, the fragile balance between the reality and the fantasy dimension in our sexual activity gets disturbed, and the fantasy transgresses into reality. Erika Kohut in The Piano Teacher (2001) is a character with deep repressed sexual emotions. She is a person who is not yet sexually subjectivized. She likes the ‘phantasmatic coordinates’ of her sexual desires. This accounts for the scene of her visit to a pornographic video store and watching a hardcore film. Slavoj Zizek argues here that her act is not to get aroused but to learn all the coordinates of desire – how to have sex or even how to get excited. She gathers that knowledge from the virtual images and tries to enact them to get the experimental sense of the real from the virtual. She writes a letter disclosing all her fantasies to her lover, Walter. And, Walter does exactly that. He has intercourse with her in the most brutal way possible, exactly as described in her letter. But enacting the exact things, Erika's fantasy gets lost. According to Zizek, 'when fantasy disintegrates, you don't get reality. You get some nightmarish real, too traumatic to be experienced as ordinary reality.' As a result, the perverse heaven of 'fantasy' becomes a hell.

Objectification of Life:

As I mentioned earlier, as a Westerner, Haneke critically studies the consumer capitalist social structure of the West in his films. Each of his films (except The White Ribbon, 2009) consists of characters who belong to the bourgeois upper class, and have all the privileges to conform, signifying this social structure in a microcosm. With this study, Haneke tries to address the 'objectification of life' within this social structure and how people are affected by it.

The best example of this 'objectification of life' is Haneke's debut feature, The Seventh Continent (1989). Tracing the lives of husband Georg, wife Anna, and daughter Eva, he presents a world in which this outwardly successful family, in fact, functions as mere appendages to the objects around them. This is made evident in the opening scenes of the first part of the film in which Haneke systematically deprives the viewer of facial close-ups for over ten minutes, drawing our attention instead to a range of quintessentially 'bourgeois' objects: the alarm clock, the fish tank, the coffee maker, and the car. By capturing this object, he allegorizes the fact that the family cannot truly take hold of the space of the object world which leads them to be seized by the world and self-sacrificed to it. Interestingly, their final self-destruction is not an act of wild revolt or nihilistic protest against the inertia of this world but the slow, mechanical repetition of that world in a negative form. We see how they first accumulate further objects (hammers, saws, and other tools) to take apart the objects that surround them. The methodical and largely lifeless destruction of these objects and, almost unbearably, the mechanical act of suicide signify not freedom but their final capitulation to the dead state of being objects among objects. The 'objectification of life' becomes complete.

In The Seventh Continent, the idea of this 'objectification' is constructed within the bourgeois space filled with commodities. But what if the bourgeois space gets completely stripped of these commodities? In Time of the Wolf (2003), Haneke showcases an apocalyptic world where the 'necessities' of modern culture have instantly lost all value. The purpose and relative worth of space and material objects have been mercilessly readjusted; a lighter is extraordinarily valuable, while a watch is worthless. But in this situation, the 'objectification of life' still finds a path. The people have to sell their bodies for sexual favors to get water, or animals are killed mercilessly for their meat. In both of these instances, Haneke tries to convey a materialistic desensitization of life. First, in a world where everything is readily available and consumed, and the other in a post-apocalyptic space where humankind is stripped to its primitive state.

Hospitality in a Cosmopolis:

“Hospitality is culture itself and not simply one ethic amongst others. Insofar as it has to do with the ethos that is…one’s home… since it is a manner of being there, how we relate to ourselves and others, to others as our own or as foreigners, ethics is hospitality.” - Jacques Derrida

In 1996, Jacques Derrida addressed the International Parliament of Writers in Strasbourg on the issue of 'cosmopolitan rights' for refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants. In that address, later published under the title "On Cosmopolitanism," he raised the possibility of a new instantiation of the historical 'cities of refuge,' an 'open city' emerging out of and requiring a new cosmopolitics that encompasses both the duty of and right to hospitality. Within the context of global cities and globalization, such a cosmopolitics would require us to think about hospitality, democracy, and justice beyond the borders of the nation-state; it would, in effect, require the creation of a new political imaginary.

But speaking of that, Derrida points out, however, in practice, hospitality of this type is not possible without further conditions. First, to offer hospitality, one must be the 'master' of the house or the nation – one must, in some sense, control it, have sovereignty over it – to 'host' at all. But the control does not stop there, for the host must have some degree of control over his guests as well. If they take over the house, he is no longer the host. Extending hospitality might, given a bad guest, result in the displacement, undermining, or destruction of everything. The host, therefore, has the duty, Derrida argues, 'of choosing, electing, filtering, selecting (his) invitees, visitors, or guests, those to whom (he) decides to grant asylum, the right of visiting or hospitality.'

In Code Unknown: Incomplete Tales of Several Journeys (2000), Haneke showcases these exact problems with hospitality through the several interactions between the characters. In the very first scene after the opening credits, we can see a chance encounter at a busy Paris intersection that brings together Anne, a Parisian actress; Jean, a young French man from the provinces; Marie, an illegal immigrant from Romania; and Amadou, a young teacher who is the son of Malian immigrants. Entitled 'Ball of Paper' in the script, the scene begins with Anne coming out of the door of her apartment building onto a busy street. Jean, the younger brother of Anne's boyfriend Georges, is waiting for her outside. He has run away from his father and the farm, he explains, and he needs a place to stay. He would have come upstairs, but the code to the electronic lock on the door had been changed, and he did not know the new one. He tried to call, but Anne was in the bath and did not hear the phone, so he got the answering machine. His brother Georges is away, Anne tells him, photographing the war in Kosovo, and she is on her way to a meeting. She and Jean have a quick conversation as they walk, and, after buying him a pastry and reminding him that 'there isn't room for three' in her apartment, she gives him the code and the keys.

On his way back, Jean passes Marie, who is sitting against a wall just inside an alley, begging. He tosses the empty, crumpled-up pastry bag into her lap and keeps going. But Amadou sees this and decides to intervene. He confronts Jean, asking him, 'Was that a good thing to do? Do you feel that was right?' and demands that he apologize to the woman. They scuffle, Anne returns and demands to know why Amadou is beating up on Jean, and the police arrive. They ask for everyone's papers, they arrest Amadou, and the next time we see Marie, she is being escorted, in handcuffs, onto a flight back to Romania.

On multiple levels, this scene might be understood as a series of failures of hospitality: Jean's failure to offer hospitality to Marie (which is then made 'official' by the police), but also Anne's failure to offer hospitality to Jean (which might be part of what triggers Jean's subsequent mistreatment of Marie) and, finally, the failure of Amadou's attempt to correct the situation with Marie by forcing Jean to apologize and acknowledge her right to be treated with dignity, and thus to reinstate hospitality.

In Haneke's point of view, the codes for hospitality are unknown in a globalized cosmopolis. Perhaps that is the ultimate meaning of Haneke's title. With this film and others such as Happy End (2017), he tries to critique these normalizing aspects of the failures of unconditional hospitality of the West, particularly in any so-called globalised cosmopolis.

The Burden of the West:

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned that Haneke’s films deal with the fallacy of the ‘utopian modernity’ of Western countries. To signify this ‘utopia’, he uses the motif of the perfect bourgeois upper-class lifestyle, where every amenity is readily available. But under this utopia, there exists an omniscient and omnipotent anxiety. In Haneke’s films, one of the key motifs for this anxiety comes under the ‘colonial guilt’.

In the 16th century, the Westerners started this colonization as their exploration of the world. In this process, they imposed their cultures and belief systems on people they viewed as primitive. In the Westerners' argument, they brought modernity to these colonies that helped them to catch up with what was (and still is) viewed as being the proper way of living. In simple words creating a ‘utopia’. But this is a naive concept and by accepting it, the Westerners try to get into denial of the sins they commit in their way of bringing modernity to these colonies. This denial creates a repressed state of mind, which often comes in uglier ways in terms of ‘colonial guilt’. Haneke often examines this repressed state of denial often with his films. Most particularly in his French language films such as Code Unknown (2000), Cache (2005) and Happy End (2017).

In Cache, this ‘colonial guilt’ in its personal and collective form becomes the main focus of the narrative. Here the guilt comes from the disturbing event of the massacre of French-Algerians in a peaceful protest against the ongoing Algerian War on the night of 17th October 1961, by the Paris police and its denial by the French government afterwards. Haneke takes this collective denial and transpires it with the personal in Cache. Like the French government denies anything related to a massacre for a long time, Georges denies doing anything wrong with Majid. For him, it is just a child’s mischief to tell lies about Majid that eventually results from his expulsion from his (Georges) house. So, he can’t be accountable for Majid’s situation, deprived of a good education and a good life. As I mentioned earlier the denial gives rise to repression and this comes out as a ‘Freudian Nightmare’ – the anonymous tapes of surveillance. This repression is omniscient and omnipotent for Western countries like France and its people. Haneke’s infusion of the collective with the personal creates a larger image of a ‘negative utopia’.

The Roots of Evil and Thereafter:

Winner of the 2009 Palme d’Or at Cannes and nominee for Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award, The White Ribbon seems to be thoroughly out of the past. Shot in sharp, high-definition digital and converted into black and white during post-production, the pre-World War I historical reconstruction marks a departure from the urban landscape in earlier Haneke films. Until this point, Haneke’s films capture the lives of the bourgeois upper class (a signifier of modernity) and the dread beneath their perfect lives. But in The White Ribbon, Haneke attempts to examine the pre-modern times and finds the root causes of the dread that follows in modernity.

The plot documents the ‘strange events’ that afflict a Northern German village and its principal characters: the Baron’s family, the Pastor’s family, the Farmer, the Steward, the Midwife and the village Doctor. The Schoolteacher, who is also the retrospective storyteller, narrates the proceedings, intercut with the subplot of his courtship of the Baroness’ nanny, Eva; the Doctor’s horse is felled by a wire; the Farmer’s wife dies in an accident at the mill; the harvest is destroyed and a barn goes up in flames; Baron’s son, Sigi, is kidnapped and beaten; Karli, the Midwife’s handicapped son, is attacked so severely that he can hardly see.

Haneke does not resolve these strange events like any other of his films (like we don’t get the answer in the end who sent the videotapes in Cache, 2005). Rather he portrays the social sickness that perhaps triggers the events to occur. The children face constant physical and sexual abuse. For example, the Pastor and his wife employ (based on today’s standards) draconian disciplinary measures; when the father suspects Martin of self-exploration, he has his son’s hands bound to the bed at night to prevent impropriety or Klara gets humiliated in front of her whole class for not maintaining the decorum at school. The other characters are also engaged in amoral acts as the baron exploits the peasant’s family by stripping away their social status and persecuting them into oblivion or the doctor sexually abuses the midwife and his own daughter.

These events are equally strange and sick as the so-called ‘strange events’ occurring in the village. The social construction of violence—how it is passed down in families, in schools and by religion—is always at issue in this film, subtitled “A German Children’s Story”. The Doctor’s sexual abuse of his daughter, the general severity and hypocrisy of the village adults and class tensions are played out in the children’s increasing aggressions and it is implied that they are also responsible for the ‘strange events’. One of the final scenes—when the Midwife inexplicably needs to leave town and a tracking shot reveals that the children are trying to gain access to the Midwife’s house, where the battered Karli had been convalescing—recalls Funny Games’s (1997 and 2007) sinister dénouement, when we realise that the killers will strike again and again. In this tale, children mobilise for a generational struggle not by rebelling, but by overlearning their lessons and taking the adults’ moralism literally. By showcasing this Haneke allegorises the omnipresent nature of evil. Once it is rooted, it only grows thereafter – to Benny (Benny’s Video, 1992) or Maximilian B (71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, 1994).

Amour and the New Way of Ethical Questioning:

After winning his second Palme d’Or and his first Academy Award for his film Amour (2012), Haneke cements his position as one of the most important filmmakers of modern times. After dealing with the past in The White Ribbon (2009), Haneke returns to his known urban landscape. But in his entire career, for the first time, he captures the lives of an elderly couple standing in their last stages of life. The story of another Georges and Anne focuses on the issue of how to manage the suffering of someone you love. At the beginning of the film, Anne suffers from a stroke, which leaves her one side paralyzed. Throughout the film, her health deteriorates, and the only obvious thing is death. But in these harrowing moments of their life, Georges and Anne’s love stands still. And showcasing the moments of love and care explicitly, Haneke perhaps introspects his career as a moralist.

Mark Kermode says in his review that Amour is an anti-thesis of Funny Games (1997 and 2007). Funny Games is the film where Haneke tries to question the morality of the viewer in the consumption of (violent) images. Thus, he prevents us from looking into them with self-imposed constrictions and a shameful gaze by the protagonists. On the flip side, Amour showcases the empathetic encounters between Georges and Anne with more humanity than any of his other films. I think in the twilight of his life and career (after Amour, he only made Happy End in 2017), Haneke poses new kinds of moral questions with his bleak worldview. Becoming more empathetic towards his characters and sympathizing with them with humanity is just a façade of modern ‘utopia’. By taking this stance, he manipulates the audience to believe the literal care and love they expect from any romantic movie. But underneath, there lies the dreadful moral and political allegory. Georges’s act of helping Anne in her euthanasia thus poses the same ethical questions about the ‘utopian modernity’ but in a much more humanistic way.

Conclusion:

When I sit to write this article, I often have to introspect my thoughts. To understand a filmmaker like Haneke, it is not easy to generalize and streamline the whole picture. His films consist of many layers, and each layer has its own independent version of truth. With each viewing and re-viewing, we can get a little closer to that truth. And perhaps by facing these truths, we can finally answer the unsolvable questions. Perhaps, then we can find the real ‘utopia’.

. . .

References:

- Auge, Marc (1995)‘Non-places. Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Trans. J. Howe. London: Verso.

- Baudrillard, Jean (1979) ‘De la seduction. Paris: Denoel-Gonthier.

- (1983) ‘Simulations’. Trans. P. Foss, P. Patton and P. Beitchman. New York: Semiotext(e).

- (1990) ‘Von der absolution Ware’, trans. M. Buchgeister, in H. Bastian (ed.), ‘Andy Warhol: Silkscreens from the Sixties. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel.

- Deleuze, Giles and Felix Guattari (2004), ‘Anti Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. R. Hurley, M. Seem and H. R. Lane. London: Continuum.

- Derrida, Jacques and Anne Dufourmantelle (2000), ‘Of Hospitality: Anne Dufourmantelle Invites Jacques Derrida to Respond’. Trans. R. Bowlby. Stanford: Stanford University, Press.

- Derrida, Jacques (2001), ‘On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness’. Trans. M. Dooley and M. Hughes. London and New York.

- Frey, Mattias (2010), ‘A cinema of disturbance: the films of Michael Haneke in context’, Senses of Cinema.

- Frey, Mattias, ‘Supermodernity, Sick Eros and the Video Narcissus: Benny’s Video in the Course of Theory and Time’ [as collected in The Cinema of Michael Haneke: Europe Utopia, Columbia University Press, 2011, edited by David Sorfa and Ben Mccann].

- Gerbaz, Alex, ‘The Ethical Screen: Funny Games and the Spectacle of Pain’[as collected in The Cinema of Michael Haneke: Europe Utopia, Columbia University Press, 2011, edited by David Sorfa and Ben Mccann].

- Geyh, Paula E., ‘Cosmopolitan Exteriors and Cosmopolitan Interiors: The City and Hospitality in Haneke’s Code Unknown’[as collected in The Cinema of Michael Haneke: Europe Utopia, Columbia University Press, 2011, edited by David Sorfa and Ben Mccann].

- Kermode, Mark (2008), ‘Scare us, repulse us, just don’t ever lecture us’ - the title of his review on Funny Games US.

- Levinas, Emmanuel (1969), ‘Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Trans. A. Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne Univerisity.

- Michael Haneke on Violence - cine-fils.com, YouTube Link: www.youtube.com/watch, Interview Taken by Felix von Boehm, Vienna, March, 2009.

- Michael Haneke: Interviews, University of Mississippi Press, 2020. Interviewed by Stefan Grissemann and Michael Omasta.

- Nicodemus, Katja; Assheuer, Thomas ‘Fear is the Deepest Emotion’ from Die Zeit (2006) [as collected in Michael Haneke Interviews, University of Mississippi Press, 2020].

- Noys, Benjamin, ‘Attenuating Austria: The Construction of Bourgeois Space in The Seventh Continent’ [as collected in The Cinema of Michael Haneke: Europe Utopia, Columbia University Press, 2011, edited by David Sorfa and Ben Mccann].

- Sontag, Susan (2003), ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- The Cinema Cartography, ‘The Tragic Side of Cinema’ - segment on 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, YouTube Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch

- Zizek, Slavoj (2006), The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema.