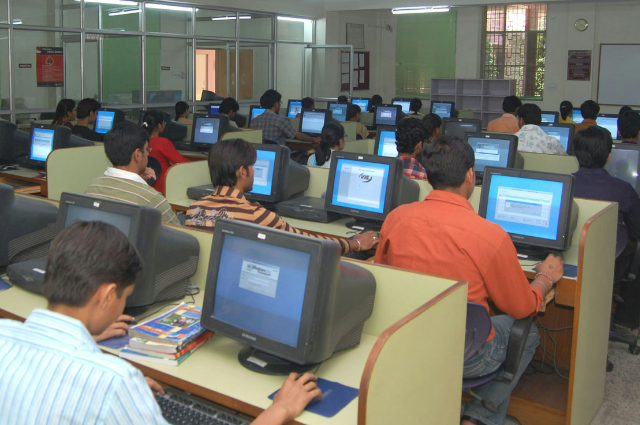

Photo by sunrise University on Unsplash

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 heralded a new era for Indian education, placing the teacher at the centre of reform and urging the integration of technology in teaching and training. Under NEP’s vision, teacher education is being overhauled to align with 21st-century needs. This means blending pedagogical excellence with digital fluency: pre-service programs and in-service professional development are being redesigned to include modern edtech tools, online learning, and ICT (information and communication technology) skills. By leveraging platforms like DIKSHA, NISHTHA and SWAYAM, alongside emerging tools in AI, AR/VR, and data analytics, India is reimagining how teachers are trained. These efforts aim to empower educators with adaptable skills, rich resources, and continuous learning opportunities while also addressing equity and inclusion. In turn, teachers become innovators and content-creators who can deliver engaging, personalised instruction in any setting—urban or rural. The transformation of teacher education under NEP 2020 is not merely about digitising old methods, but about building a connected ecosystem that fosters collaborative learning communities, open resources, and lifelong professional growth for educators across India.

NEP 2020’s Vision for Teachers and Technology

NEP 2020 explicitly recognises teachers as “the most respected and essential members” of society and outlines a roadmap for revamping their education and development. The policy mandates stronger pre-service training (reforming Bachelor of Education degrees into four-year integrated programs) that includes technology integration and hands-on practicum. For example, all B.Ed. Programs are to cover “time-tested as well as the most recent techniques in pedagogy,” with particular attention to educational technology and learner-centred, multi-level methods. Similarly, in-service teachers are expected to undertake ongoing professional development through blended methods. NEP encourages using nationwide digital platforms (SWAYAM, DIKSHA) for standardised online training of teachers to reach large numbers quickly. Key NEP provisions aligned with digital innovation in teacher education include:

- Technology Integration: Extensive use of ICT is prescribed in teaching, learning, and evaluation, with special modules for “integrating ICT in teaching, learning, and assessment”. This ensures teachers are comfortable using digital tools in classrooms.

- National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education (NCFTE): A new framework (by 2021) is to incorporate NEP goals, likely weaving digital pedagogy into core competencies.

- Online Teacher Training: Platforms like DIKSHA and SWAYAM are explicitly named for delivering high-quality courses and modules to teachers across states, making professional education more accessible.

- Inclusive and Multilingual Digital Content: The policy emphasises removing language barriers and increasing access, encouraging the creation of open digital resources (such as e-textbooks and lectures) in multiple languages and formats for diverse learners.

- Innovation and Quality: NEP calls for open, interoperable digital infrastructure (as advanced later by NDEAR) where startups and innovators can build new solutions for teachers, guided by principles of scalability, resilience, and data privacy.

- Together, these NEP provisions set a clear expectation: Teacher education must evolve with technology, not as an add-on but as a core element. In practical terms, this means a newly graduated teacher should be as savvy with online lesson design, educational apps, and data-driven assessment tools as with chalkboard instruction. It also means seasoned teachers should be offered continual upskilling on edtech trends and digital best practices.

Leveraging National Platforms: DIKSHA, NISHTHA, SWAYAM, and NDEAR

The Government of India has built or adopted several digital infrastructure platforms that serve as cornerstones for teacher training and resources. These platforms exemplify the scale and ambition of India’s digital push:

- DIKSHA (Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing): Launched in 2017, DIKSHA is a national digital repository for school education, offering lesson plans, assessments, and modules for both students and teachers. States and boards customise it, creating and curating content. Crucially, DIKSHA hosts teacher training courses and quizzes and is the delivery vehicle for NISHTHA training. By 2023, DIKSHA had become one of the world’s largest education platforms: it offers thousands of courses and hundreds of thousands of learning resources in over 30 Indian languages. According to government updates, over 135 million courses have been completed on DIKSHA, with participation from roughly 180 million students and 7 million teachers. Another measure of scale: as of mid-2024, DIKSHA saw over 3.5 billion page views and 50 million users. These statistics reflect its deep penetration — all states/UTs and major curricula boards use DIKSHA in some form. For teachers, DIKSHA offers free online continuing-education units on pedagogy, subject updates, and digital literacy. For instance, during COVID-19, NCERT introduced DIKSHA-based webinars and modules on ICT tools and online teaching, ensuring teachers could transition to digital classrooms.

- NISHTHA (NISHTHA – NIPUN Bharat): This is the flagship National Initiative for School Heads’ and Teachers’ Holistic Advancement. Initially conceived in 2019 as a face-to-face training program, it was rapidly adapted to an online modality (using DIKSHA) during the pandemic. NISHTHA provides activity-based modules on school leadership, inclusive education, continuous assessment, and more. By mid-2021, nearly 2.4 million teachers at the elementary level had completed NISHTHA training. NISHTHA’s reach is enormous: it aims to train about 4.2 million teachers and school leaders across the country. The dashboard data (from NCERT) shows tens of thousands of in-person workshops and millions of self-paced online completions. NISHTHA modules now routinely include digital pedagogy – e.g., a dedicated module on using ICT in teaching was added to align with NEP’s focus on tech integration. For teachers, NISHTHA represents a systematic upskilling path: they can log into DIKSHA, enrol in NISHTHA courses, participate in webinars, and earn digital certificates. This ensures that even remote educators can access quality training content developed by experts.

- SWAYAM and SWAYAM Prabha: SWAYAM is the government’s MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) platform, hosting over 3,000 courses on higher education and teacher development. In higher education, SWAYAM has seen over 30 million enrollments since its 2017 launch (with more than 2.4 million enrolling in exam-credit courses). For teacher education, SWAYAM offers teacher-specific courses – for example, a “NEP 2020 Professional Development” credit course launched by NITTTR, or subject pedagogies created by National Institutes of Teachers’ Training (NITTTRs). Notably, SWAYAM’s popularity among educators spiked after COVID: a ministry letter noted a “surge in enrolment for courses in the education domain post-pandemic,” reflecting teachers’ desire to learn ICT-led teaching methods. Over 300 universities now recognise SWAYAM credits, allowing teacher-training institutes to count these courses towards professional development. Meanwhile, SWAYAM Prabha TV channels (12 dedicated TV channels covering grades 1–12) provide offline content — also accessible via satellites — ensuring teachers in areas with limited internet can still receive lectures, and in some states even training broadcasts.

- National Digital Education Architecture (NDEAR): Though less visible, NDEAR is a foundational initiative to standardise and interconnect these platforms (and others like e-pathshala, Digital Textbook portals, etc.). Launched in 2022, NDEAR provides open APIs and services so that DIKSHA, SWAYAM, UDISE+ (school database), and other systems can “talk” to each other. For teachers, this means a unified login and data portability: their profile and training credits can follow them across systems. In the long run, NDEAR will enable personalised dashboards, adaptive learning analytics, and plug-and-play edtech solutions (e.g., apps that can feed into DIKSHA or retrieve student reports securely). While NDEAR is a technical initiative, its significance is strategic: it embodies the NEP principle of an open, scalable digital infrastructure that fosters innovation and avoids vendor lock-in.

Together, these platforms have democratized access to teacher education resources. Even teachers in small villages can attend a live webinar on DIKSHA, earn a MOOC certificate via SWAYAM, and download language-specific teaching aids from an open repository. This nationwide connectivity is unprecedented: in 2024 alone, tens of millions of learning interactions took place on DIKSHA, and nearly 17 million participants (teachers and school heads) engaged in NISHTHA programs. The emphasis on free, high-quality, multilingual content ensures that no teacher is left behind.

Blended and Online Teacher Training

Under NEP, the mode of teacher training is deliberately moving towards blended learning – combining traditional face-to-face mentoring with robust online components. This hybrid approach has several advantages. First, it scales up reach: a single webinar can train thousands, whereas in-person workshops are limited by geography and cost. Second, it introduces flexibility: teachers can learn at their own pace, revisiting recorded lectures or discussion boards as needed. Third, it models the very methods (flipped classrooms, self-paced modules) that NEP encourages teachers to use with their own students.

During COVID-19, India’s reliance on blended training became a necessity. Institutions quickly shifted induction and refresher courses online. For example, NCERT’s NISHTHA online modules launched in October 2020 (via DIKSHA), enabling millions to complete their training even during lockdowns. Simultaneously, university departments and State Councils of Educational Research and Training (SCERTs) began offering virtual practicum and teaching practicums through video conferencing.

Today, many B.Ed. and M.Ed. colleges are permanently integrating online elements. A future teacher might spend part of the term in a MOOC on digital pedagogy (earning credits), then conduct a micro-teaching session on Zoom for classmates, and later join a local school practicum under a mentor teacher. This end-to-end blended model is still evolving, but early pilots show promise. For instance, some teacher training colleges collaborate with DIKSHA to use its content in the classroom: student-teachers develop lesson plans using DIKSHA quizzes and videos, and peer-review them on the platform. Key features of blended teacher training under NEP include:

- Flipped Classrooms for Trainees: Pre-service courses encourage teacher trainees to watch digital lectures (often from SWAYAM or NCERT) at home and use contact hours for discussion, reflection, or lesson design.

- Peer Learning Networks: Online communities (WhatsApp groups, DIKSHA forums, Facebook groups moderated by SCERTs) connect trainees and in-service teachers across regions. They share resources, ask questions to experts, and crowdsource solutions to classroom challenges.

- Micro-credentialing and Badges: Continuous online learning modules often award micro-credentials (digital badges) in areas like “ICT-enabled Pedagogy” or “Inclusive Teaching.” Over time, these accumulate in a teacher’s profile, signalling skill mastery beyond formal degrees.

- Virtual Classrooms and Teaching Simulations: Some programs use virtual classrooms (e.g., simulated video classes or VR environments) to give trainees a chance to practice teaching without being physically present in a real classroom. These simulations can expose trainees to diverse scenarios – large classes, multi-grade contexts, or special-needs students – in a safe, controlled way.

The blended approach does face hurdles (discussed later), but its strategic emphasis in NEP 2020 shows confidence that many barriers (distance, scheduling, travel cost) can be overcome by tech. By 2025, we can expect blended training to become the norm in most states, with physical workshops complemented by a robust online curriculum on platforms like DIKSHA and SWAYAM.

Digital Content Creation and Open Resources

A central pillar of NEP’s digital strategy is to promote rich content development and sharing by teachers themselves. Under DIKSHA and related initiatives, teachers are no longer just consumers of content but active creators of OER (Open Educational Resources).

- Open Content by Teachers: Platforms like DIKSHA invite teachers to contribute lesson plans, quizzes, videos, and assessment items. For example, as part of the DIKSHA initiative, state governments and educational boards organised content creation drives where experienced teachers developed digital lessons aligned to new curricula. This crowdsourced content generation has led to tens of thousands of new resources in regional languages. The open licensing means any teacher nationwide can adapt these materials. This creates a virtuous cycle: as teachers learn digital skills, they then use those skills to publish their own teaching aids.

- Collaborative Content Development: Through the National Digital Library of India (NDLI) and Federated Content initiatives, teacher educators collaborate with universities and NGOs to produce high-quality multimedia. A specific case is the Shiksha Sankalp program in Rajasthan, which, while focused on training, also enabled teachers to create sample lesson videos demonstrating competency-based approaches (this became a digital model for others). Similarly, Kerala’s digital “SmartClass” project produced animated modules on pedagogy for use in teacher training.

- E-Textbooks and Learning Materials: The government’s e-pathshala and EkStep platforms, bolstered under NEP, offer free digital textbooks and interactive modules. Teacher education programs now often require trainees to prepare lessons using these e-books, integrating animations or augmented reality (AR) features. This familiarity empowers teachers to flip classroom materials for their students.

- Offline and Multilingual Access: Recognising connectivity gaps, digital content is often made downloadable for offline use. DIKSHA, for instance, provides QR codes in printed textbooks (the “energised textbooks” concept) that link to videos or exercises that can be downloaded at district ICT labs. Teacher training centres have also adopted low-bandwidth content like audio lectures and podcasts; NCERT’s Radio Web services produce podcasts on pedagogy topics specifically for teacher students.

By focusing on content creation, the NEP-era reforms treat teachers not just as recipients of training but as knowledge producers. Over time, this is expected to cultivate a large repository of best-practice videos, case-study simulations, and lesson demonstrations designed by India’s own educators. For example, a math teacher might record a video of herself using a tablet app to teach algebra to students with learning disabilities; after peer review, that video goes online for all teachers to learn from and adapt. This approach democratizes expertise: best practices found in a remote school can spread nationwide.

Emerging Technologies: AI, VR/AR, and Beyond

Looking ahead, next-generation technologies are poised to further revolutionise teacher education. While still nascent in India’s public system, initiatives in Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR), and Augmented Reality (AR) are being piloted and studied for teacher training.

- Artificial Intelligence: AI can support teachers by personalising professional development and reducing routine workload. For example, adaptive learning systems can recommend targeted training modules based on a teacher’s profile and performance, much like a recommendation algorithm suggests courses on DIKSHA. AI chatbots (for instance, like Khan Academy’s Khanmigo, now available in English and Hindi) are being adapted to serve as on-demand mentors for teachers, answering questions about pedagogy or content standards. In higher education, the NEAT (National Educational Alliance for Technology) platform partners with edtech innovators to provide AI-based tutoring; similar AI tools could be extended to pre-service teacher candidates for subject mastery or skill assessment. Additionally, AI-driven content generation (e.g., creating math problems or language exercises) can help teacher educators quickly build repositories of practice materials. However, this area is evolving, and concerns around bias and oversight are being studied. The NEP’s reference to machine learning in general curricula suggests that AI literacy for teachers (and for teaching) will grow over the coming decade.

- Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR): Immersive technologies are especially promising for simulated teaching practice. An example from India is IIT Madras’s AR/VR projects (though aimed at school learning, they illustrate the potential). Researchers there created an AR app “MemoryBytes” for history learning, but their broader goal is VR-enabled learning environments for social science, science, etc.. Similar technology could be used to give teacher trainees virtual classrooms. For instance, a VR simulation might mimic a crowded multi-grade classroom in a rural area, allowing a trainee to practice classroom management and adaptive teaching in a risk-free environment. Another use is virtual laboratory training: science teacher trainees could use VR lab simulators to conduct experiments remotely, an idea NEP encourages for both STEM labs and digital pedagogy. Although still pilot-scale in India, foreign universities and companies (e.g., U.S. “TeachLivE” virtual classrooms, or simulated teaching games) are already training teachers this way. As hardware becomes cheaper (e.g., smartphone VR headsets) and content is localised, these AR/VR tools could see wider adoption, especially in teacher-training institutes affiliated with technology-forward states or universities.

- Immersive Digital Content: Relatedly, AR apps and interactive games are enriching pedagogical skill-building. Some student-teachers are already using AR storybooks or language apps in practice sessions, testing how these tools change student engagement. Over time, NEP envisions more “gamified” modules and mixed-reality experiences in teacher ed. Imagine a future course module where an aspiring science teacher uses an AR overlay to tag and explore plant anatomy in his own backyard before coming to class.

These emerging technologies are not meant to replace foundational training but to augment and expand it. They offer novel practice environments, especially useful when real-world training opportunities are limited. NEP 2020’s emphasis on tech-enabled learning sets the stage for such innovations; as the policy suggests, India’s teacher education can leapfrog by adopting tech “built on open standards” and through public-private partnerships (AICTE has run hackathons for education apps, for instance). However, scaling these techs requires careful pilot testing, teacher support, and funding – themes we return to below.

Role of EdTech Startups and the Private Sector

Beyond government platforms, India’s vibrant EdTech sector is playing an increasingly important role in teacher education. While most EdTech startups initially focused on student learning, many are now pivoting or extending to support teachers:

- Professional Development Portals: Several startups and online educators have launched Continuing Professional Development (CPD) programs. For example, large MOOC providers like Unacademy and Coursera offer courses in pedagogy and educational leadership that teachers can enrol in. By 2024, Unacademy had enrolled thousands of educators into its “Teach for India” initiative, training them in online pedagogy and content creation. Similarly, companies like Lido (initially a coding edtech) began offering training programs for school teachers to enhance STEM teaching.

- Teaching Tools and Content Providers: Startups that build tools for classrooms also contribute to teacher training. BYJU’S, for instance, runs a Teacher Training College that certifies teachers in integrating its adaptive learning app in math classes. Educomp and similar companies have modules to train teachers on digital class setup and lesson planning. These proprietary trainings complement government efforts by focusing on the practical adoption of new tech in everyday teaching.

- Analytics and Mentoring Platforms: Emerging companies are using AI and analytics to mentor teachers. For example, Cuemath (a math edtech) provides real-time feedback to teachers on how students are responding to digital lessons. EdNarrative and others analyse classroom video (with consent) to give teachers insights into student engagement, which becomes a professional learning tool. While not widespread yet, such tools embody the kind of tech incubators NEP hoped to leverage.

- Content Localisation Startups: A unique Indian angle is the push to produce content in regional languages. Startups like Avanti Learning have expanded teacher training in science by creating videos in multiple vernaculars, which train teachers on subject pedagogy in their home language. Startup-driven community networks (e.g., Telegram channels for TNPSC group discussions or X prepared by teachers) have also formed grassroots PD communities.

In essence, the EdTech ecosystem serves as an innovation engine. Startups can pilot new models (like live workshops on Zoom, virtual coaching, or AI-driven lesson planners) and then partner with government agencies or NGOs for wider rollout. NEP’s encouragement of “open, plug-and-play” digital architecture invites such collaboration. The main challenges here are ensuring quality control and equity – many edtech offerings are freemium or private. Going forward, public-private partnerships might include vetting digital courses, co-developing AI tools (e.g., partnering with IndiaAI on teacher training), or licensing startup content into DIKSHA.

Challenges: Equity, Access, and Capacity

While the digital transformation of teacher education holds great promise, the journey is uneven and faces persistent challenges:

- Digital Divide and Infrastructure: The foremost concern is unequal access. Even as millions of teachers can log into DIKSHA, there are remote areas where electricity outages, poor internet bandwidth, or a lack of devices hinder adoption. Official reports note that states like Bihar, Odisha, and parts of the Northeast still struggle with connectivity. In these regions, teachers may receive training materials on USB drives or through occasional teleconferencing, but sustained online engagement is low. Government initiatives (BharatNet fibre rollout, free smartphone schemes, PM eVIDYA radio) attempt to bridge the gap, but broadband remains spotty in many rural districts. This infrastructure gap means that without focused investment, digital initiatives could inadvertently widen existing inequities: urban and well-off teachers surge ahead, while marginalised educators fall further behind.

- Language and Content Gaps: NEP emphasises mother-tongue education, yet much high-quality digital content is still primarily in English or Hindi. Teachers in Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, or tribal language areas may find fewer resources on DIKSHA or SWAYAM. Some states have started translating modules or funding regional content developers, but the pace is slow. Moreover, teachers with limited digital literacy might prefer printed guides and only gradually acclimate to videos or apps. To ensure inclusion, training programs need to be multilingual and culturally relevant, not just transcriptions of English modules.

- Teacher Preparedness and Motivation: A digital tool is only as effective as its user. Many in-service teachers (especially older cohorts) lack prior experience with online learning themselves. Some may be intimidated by new technology or wary that computers will replace them. Training in basic digital skills (email, mobile apps) is often needed before pedagogical tech training can succeed. Furthermore, teachers are overworked and may not view extra online courses as a priority without incentives. NEP’s prescriptions – for example, linking certification to career advancement – are intended to boost motivation, but implementation varies.

- Quality and Relevance of Digital Training: Not all online courses are well-designed. Self-paced modules without human facilitation can lead to low completion rates. Educators also point out that some digital courses are generic and don’t address local classroom realities. For example, a primary science teacher in a rural school might need training on locally available teaching aids, but instead receives a standardised online lesson on digital microscopes (which her school cannot afford). Ensuring that digital content remains context-sensitive is a key pedagogical challenge.

- Assessment and Accountability: With widespread online training comes the question of quality assurance. How do we know a teacher has truly absorbed skills from a MOOC or webinar? Mechanisms like proctored exams (as on SWAYAM) help in higher ed, but for school teachers, robust credentialing is still evolving. States are experimenting with digital badging systems and integrating training progress into service records, but the systems are new. Without strong follow-up, there’s a risk that digital modules become a checkbox rather than a meaningful learning experience.

- Cybersecurity and Privacy: As teacher data goes online (personal profiles, training records, student data on platforms), concerns of privacy arise. NEP mentions a need for “transparency and security,” but many platforms still need stringent protocols. Government systems handle massive amounts of personal data, and training personnel have debated how to protect it. Cyberbullying or misinformation (through social media teacher groups) is a minor but real concern that educators mention.

Despite these challenges, the momentum behind digital teacher education remains strong. Importantly, the NEP framework forces us to confront these issues head-on. For equity, schemes like PM eVIDYA 2.0 and National Digital Literacy missions are being tailored for teachers, not just students. Periodic surveys and dashboards now track which regions lag in training uptake, prompting targeted interventions. And as a hopeful sign, even historically underserved teachers (women, first-generation graduates) are increasingly mobile-savvy, using WhatsApp for collaborative learning.

Opportunities and Future Outlook

The convergence of NEP 2020 with a global edtech boom presents a transformative opportunity. When executed thoughtfully, the digitisation of teacher education can yield profound benefits:

- Personalised Professional Growth: Digital platforms enable each teacher to follow a personalised training pathway. An English teacher in Mumbai can audit advanced language-technology courses, while a science teacher in Bihar focuses on low-cost experiment videos, all through the same national platform. Over time, data analytics can map a teacher’s progress and suggest targeted upskilling (e.g., a math teacher identified as weak in ICT could be nudged towards a DIKSHA module on smart-class tools). This shift from one-size-fits-all to learner-centric teacher development is a long-standing goal of NEP.

- Peer Collaboration and Communities of Practice: The networking aspect of digital platforms creates new support structures. Teachers can co-create lesson plans online, share classroom video recordings for feedback, or even collaborate on research projects. Already, initiatives like the “Shiksha Vani” radio and podcast series invite teachers to showcase success stories and innovations to the entire nation. This kind of participatory culture can help rapidly disseminate local solutions to common problems, increasing both morale and efficacy.

- Scale and Continuity: Traditional training programs are episodic – a workshop here, a seminar there. Digital modes allow continuous, scalable professional development. Annual training can now happen weekly through short webinars; learning resources can be accessed any time, reducing the loss of knowledge over school terms. This continuity means teachers remain updated on current trends (like new exam patterns or pedagogical research), which ultimately benefits students.

- Attracting New Talent: NEP 2020 also aims to professionalise teaching as a career, making it more attractive to young graduates. The presence of cutting-edge tools and opportunities for continual digital learning can entice tech-savvy youth into teaching. For instance, teacher education programs might highlight that trainees will become part of an innovative digital community, receive certifications, and have access to global knowledge factors that could elevate the profession’s prestige.

- Data-Informed Policy and Feedback: Digital teacher training leaves a trail of valuable data. Government bodies can monitor who is learning what, where the bottlenecks are, and which methods are most effective. For example, if teachers in a certain region consistently score lower on online assessments, targeted interventions can be launched. This kind of data-driven feedback loop can help continually refine teacher education policies, closing implementation gaps faster than before.

- Future Technologies: Looking further, the rise of the Metaverse, advanced AI tutors, and 5G connectivity could further transform teacher training. Imagine a global classroom simulation where Indian teachers practice with avatars of students in Paris or Nairobi – such cross-cultural experiences could be accessible on demand. The NEP’s principles of openness allow for future adaptation: as new global edtech trends emerge, India’s digital architecture is meant to absorb them.

Conclusion

The National Education Policy 2020 set an ambitious agenda: to transform education for the digital age, with teachers as its fulcrum. In the five years since its announcement, India has laid a considerable foundation. Government platforms like DIKSHA, NISHTHA, and SWAYAM have already modernised teacher training delivery, reaching tens of millions of educators with digital content and credentials. Blended learning approaches are replacing or augmenting old in-service programs, and innovative pilots in AI, AR/VR, and community-based training promise to push the envelope further. EdTech startups and private institutions are also engaging in this ecosystem, experimenting with new models and scaling best practices.

Yet, this transformation is ongoing and uneven. Technology alone cannot solve deep-rooted inequities in our education system. To truly align with NEP’s vision, digital innovations must be accompanied by sustained investment in infrastructure, relentless focus on teacher motivation and capacity-building, and inclusive policies that leave no teacher behind. Success stories from states like Kerala and initiatives like Rajasthan’s Shiksha Sankalp illustrate what is possible when digital pedagogies are embraced wholeheartedly.

In sum, digital innovation under NEP 2020 offers a historic opportunity to redefine teacher education in India. By equipping educators with the tools, skills, and community they need, India stands to unlock vast improvements in learning outcomes. As NEP implementation deepens, the hope is that our teachers will not just adapt to technology, but become co-creators of educational innovation – leveraging digital means to nurture the creativity, critical thinking, and lifelong love of learning that the policy so ardently champions.