Introduction

On a warm summer evening, I found myself engaged in a lively discussion with a group of friends over the ethics of modern philanthropy. The conversation wandered into familiar territory—billionaires, their donations, and the actual impact of their generosity. Someone mentioned Azim Premji’s quiet yet transformative work in education, while another pointed out the public spectacle of Jeff Bezos’s multi-billion-dollar Earth Fund. Opinions were as divided as ever.

This debate isn’t new, but it feels more urgent in today’s world, where glaring inequalities dominate every aspect of society. Billionaires often project their wealth as a solution to societal problems, but are they addressing the root causes, or are they merely patching the cracks while benefitting from the system?

This article delves into the ethical questions surrounding billionaire philanthropy. Are these acts of generosity genuine, or do they simply mask deeper issues of inequality and power dynamics?

When Generosity Meets Influence

One cannot discuss modern philanthropy without acknowledging the role of influence. The richest individuals on the planet—Gates, Bezos, Musk—possess wealth exceeding the GDP of some countries. With such economic clout, their donations inevitably shape the world in ways that cannot always be considered neutral.

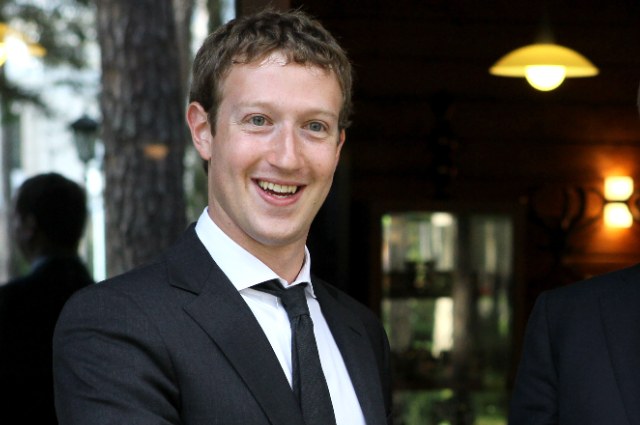

Take Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million pledge to reform schools in Newark, New Jersey, in 2010. The plan was ambitious, but its execution highlighted a glaring flaw: it was driven from the top down, with little community involvement. By the time the funds were used, consultants and administrative expenses had consumed a significant chunk, leaving behind little tangible change for the students it aimed to help.

Critics often argue that philanthropy like this wields more power than policy. By funding specific causes, billionaires effectively dictate societal priorities. Imagine a public health initiative heavily funded by a corporation—will it prioritize public well-being or align with the corporation's interests?

Rutger Bregman, a historian and author of Utopia for Realists, sums it up: “If billionaires really wanted to change the world, they’d pay their taxes and fight for systems that reduce inequality.”

The PR Side of Giving

Philanthropy, in many cases, is a double-edged sword—a blend of altruism and strategic public relations. The timing of major donations often coincides with controversies surrounding a billionaire’s business practices. Jeff Bezos’s Earth Fund announcement, while groundbreaking in its scope, was unveiled during a period when Amazon faced harsh criticism over its environmental practices and labor conditions.

These acts of generosity tend to dominate headlines, shifting focus from critical scrutiny to celebratory praise. The public is quick to applaud the billions donated, often overlooking the systems that allowed such wealth to accumulate unchecked.

Anand Giridharadas, in his provocative book Winners Take All, captures this paradox perfectly: “Philanthropy is not a solution; it is a symptom of a system that allows extreme inequality to flourish.”

When Philanthropy Works

This is not to say that all philanthropy is flawed. Some individuals have used their wealth to create sustainable, meaningful change. Azim Premji’s philanthropic work in India is a shining example of this. Through the Azim Premji Foundation, he has focused on education and rural development, addressing structural issues with grassroots participation.

MacKenzie Scott has also emerged as a powerful force in reshaping philanthropy. Unlike traditional models that demand recognition and control, Scott has donated billions to small, community-focused organizations without imposing restrictions. Her approach emphasizes trust and decentralization, allowing recipients to allocate funds based on local needs.

These examples show that philanthropy can succeed when it prioritizes humility, collaboration, and long-term impact over personal gain.

The Tax Dilemma

One of the most controversial aspects of billionaire philanthropy lies in its intersection with tax policy. Donations to private foundations often come with significant tax benefits, allowing the wealthy to reduce their tax burdens while maintaining control over how the funds are spent.

For instance, in the U.S., charitable donations can be deducted from taxable income, effectively allowing billionaires to decide how public funds are used. Critics argue that this system privatizes public decision-making, concentrating power in the hands of a few while depriving governments of revenue needed for systemic reforms.

Gabriel Zucman, an economist and expert on wealth inequality, describes this phenomenon as

“tax avoidance wrapped in the cloak of generosity.”

A Path Forward

To create a more equitable system, philanthropy must evolve. First, governments should enforce stricter regulations on private foundations, ensuring transparency and accountability. Tax policies must also be reformed to prevent philanthropy from becoming a tool for avoiding obligations to society.

Second, philanthropists must adopt a participatory approach, involving communities in decision-making processes. This not only ensures that funds are used effectively but also empowers those directly affected by societal issues.

Finally, society must shift its narrative around wealth and success. Instead of glorifying billionaires as saviors, we must focus on building systems that prioritize fairness and collective well-being.

Conclusion

Philanthropy is neither inherently good nor bad—it is a tool, and its impact depends on how it is wielded. The actions of billionaires can undoubtedly bring about positive change, but they can also perpetuate inequality if not guided by ethical principles and accountability.

As Andrew Carnegie famously said, “The man who dies rich dies disgraced.”

But perhaps the true disgrace lies in failing to question whether the systems that enable such wealth are themselves just.

The ethics of philanthropy demand a deeper conversation, one that goes beyond individual acts of generosity to address the root causes of inequality. Only then can we hope to create a society where philanthropy is no longer a necessity, but a choice rooted in shared humanity.