Part I (The Letter and the Rain)

They said she would never be brave.

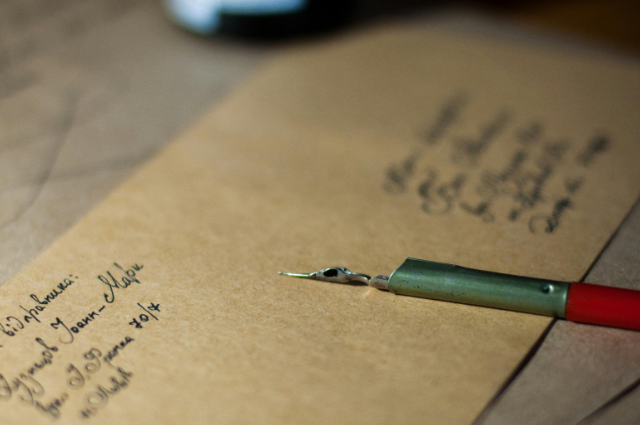

Amina folded the paper three times, each crease teaching her how to breathe. The room smelled of wet earth and cardamom; rain had pushed through the latticed window and softened the world. In the blue of dawn, she set a lamp beside her handwriting and wrote steadily, like someone carving a doorway where there had only been a wall.

She did not write to wound him. The word at the top khulā - a woman’s right to seek release. It was not defiance but release. Her hands trembled only once, when she wrote his name: Rashid. Once, his name had meant home. Now it was a roof she could no longer live under.

Their wedding came to her like an old film: her mother’s sari, his shy laugh and then the long years of silence, the cold months of waiting for warmth that never returned. Prayer had once been her refuge; now it had become an unanswered echo. The letter was not rebellion, but survival.

In the margin, she wrote the legal phrases return of mahr, date, and address. But the body of the letter was different: she wrote of the weather of her leaving, of how she had mended his shirts with her patience, and how now she must mend herself. She signed with the name that felt like arrival: Amina bint Saeed.

She folded the paper, kissed the corner, and wrapped it in muslin. For others, it was a letter; for her, a resurrection. She walked to the post office through the jasmine-scented lane, children laughing behind her, and the world suddenly felt wide.

The post office stood under an old banyan tree. Jaleel, the postman, looked up from his bicycle. She handed him the parcel with a steady voice, “Letter for Rashid.” He touched the muslin gently, nodded with quiet understanding, and slipped it into his satchel beneath municipal bills.

“It’ll reach him by evening,” he said, promising with a small God willing that folded itself into her heart.

She watched him go until he blurred between banyan trunks. Then she turned homeward, feeling the weight of her own courage settle softly on her shoulders.

At home, she swept the yard clean, boiled tea, and fed the stray cat. Freedom was still small—like a candle protected from the wind, but it burned. She prayed the evening prayer with hands that no longer shook and slept for the first time without fear of the midnight knock or the heavy silence that used to press against her ribs.

In her dream, she walked beside an old woman toward a river. Rain poured, jars filled, and the world overflowed with water enough for everyone. She woke before the end, heart steady and light.

Each day after, she moved through ordinary things, washing, listening to neighbours’ gossip, and helping with the children. Life was a soft, ongoing apology that she slowly learned to forgive.

Still, her mind drifted toward that letter travelling in a brown satchel, passing through strange hands, crossing unseen towns. Sometimes she imagined it already in Rashid’s palms, lying unopened beside his cup of tea.

At dusk, she stood in the courtyard, the call to prayer spilling over the rooftops. The words no longer commanded her to endure; they told her simply to exist.

She whispered the final salaam and looked toward the road. The postman’s bicycle had vanished into the dark. Somewhere, in the miles between them, her letter carried the weight of her freedom and the lightness of her forgiveness.

And though she did not know it, the rain that night came heavier than any in years, flooding roads, drowning streets, swallowing paper and dust alike.

Her letter, sealed with courage, had already chosen its own destiny.

Part II (The Words That Found Her)

The morning arrived like a folded page, light at the edges, blank at the heart.

Three days had passed since Amina sent her letter. The air carried the smell of monsoon rot and unspoken prayers. She had expected the world to change loudly, like thunder; instead, it changed quietly and with discipline. Each dawn, she swept the veranda, watered the jasmine, and listened to the wind pretending not to ask.

On the fourth day, Jaleel’s bicycle appeared at the turn of the lane. Her pulse leapt and stumbled. But when he stopped, it was only to deliver a neighbour’s pension notice. He smiled at her briefly, uncertain whether to mention her letter. There was nothing in his satchel for her, not even its ghost.

When he left, Amina understood something sharper than disappointment that waiting was a different kind of cage.

That evening, she went to the mosque courtyard to sit beneath the neem tree. Children were rehearsing lines for a play about Eid; their voices echoed small, joyous certainties that no adult could afford. The imam’s recitation floated outward, tender and firm. The words that once told her to endure now told her to rise.

A widow joined her, a woman who had learned to smile as resistance. “You look lighter,” the widow said. “As if you swallowed the moon.”

Amina laughed, the sound almost startling her. “Maybe I just stopped swallowing stones.”

The widow nodded approvingly, as if Amina had passed an unspoken test.

That night, Amina burned incense and read from a Qur’an her mother had given her, the page cornered with dried rose petals. She paused at a verse about forgiveness. She read it again, then once more, until it stopped sounding like an order and began sounding like a release.

Far away, in another town, Rashid sat behind the counter of his hardware shop. The world around him was ordinary nails, ropes, a calendar with an outdated crescent moon, yet a dull unease threaded through his ribs. He told himself it was indigestion, not guilt.

He had been gone from Amina’s house for six months, visiting, trading, postponing apologies. When he thought of her, he saw her eyes in fragments, the colour of old tea, the stillness of wells. He told his friends she was stubborn, that she “never understood men.” He laughed when they did, because laughter is how guilt disguises itself in public.

That evening, as the post office closed, Jaleel’s bicycle took a familiar road. The rain came suddenly and cruelly. A cart overturned, letters scattered like frightened birds. Jaleel ran to gather them, pressing them into his shirt. When he reached home, soaked to his bones, he found one envelope smeared into illegibility, the ink dissolved, the name blurred beyond saving. He placed it near the stove to dry, meaning to ask the clerk about it in the morning. But the monsoon rose all night, the roof leaked, and the paper, damp and soft, slipped under the table unnoticed.

By dawn, it was gone.

Weeks passed. No answer came. But something subtle grew inside Amina, a calm that was not waiting, and not bitterness. The act of writing had shifted the shape of her silence.

She started to teach the neighbour’s children verses and arithmetic under the mango tree. Her voice, once hesitant, carried like sunlight between leaves. She smiled more. The cat began to sleep at her doorstep instead of wandering. Freedom had come not with an answer, but with acceptance.

One noon, she was called to the post office. The clerk, nervous and apologetic, handed her a small, tattered envelope. “Came mixed with old files,” he said. “Might be yours. We can’t trace the sender.”

Her name was written in Rashid’s handwriting, careful, almost frightened.

She opened it slowly, each motion deliberate as prayer.

Amina,

If this letter ever reaches you, it means I lacked the courage to speak what I should have. I left because I thought silence was easier than forgiveness. I was wrong. I have carried your kindness like a mirror that would not lie. I am unwell. If Allah wills, perhaps I will find peace by the time you read this.

You were always braver than I knew. May your life be larger than my shadow.

— Rashid

She read the letter twice, thrice. Her hands trembled, but not from grief. There were tears, yes, but they came from some clean place inside her that pain had long ago abandoned. She walked to the window and looked out at the road. A boy passed on a bicycle, his bell tinkling like laughter.

It took her a long moment to realise what the letter meant. Rashid’s letter was dated two months before her own. Two months before, she had written the words khulā. Two months before her courage had even found its name.

They had both written and reached for each other in the same silent language — and the world, with its careless hands and flooding roads, had kept both messages captive.

That night, she placed Rashid’s letter beside her Qur’an. She did not curse the loss or the delay. She whispered a quiet prayer of gratitude and meant it.

For what was faith, if not trusting that even lost things return not as we want, but as we need?

She walked to the veranda. The air was still wet, carrying the smell of earth and smoke. Above, a slice of moon hung thin and white as a fingernail. Somewhere, a train passed, its whistle stretching across the dark like a memory leaving home.

She thought of all the letters that never reached, all the words the world misplaced and how, perhaps, God read them all anyway.

Amina smiled not in triumph, not in sorrow, but in peace.

She closed the door, leaving it unlocked. The rain began again, gentle this time, like someone knocking softly, asking to come in.

And the world, at last, understood her silence…