Photo by Jayanth Muppaneni on Unsplash

I. Introduction: Where Stones Speak – Rana Safvi's Vision of the Red Fort

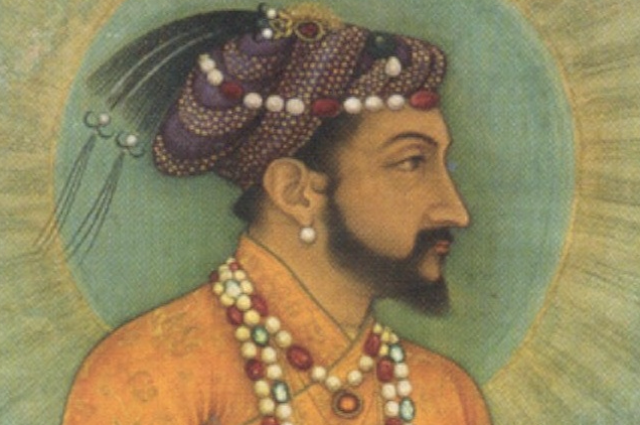

The Red Fort, a majestic sentinel standing proudly in the heart of Old Delhi, was once known as the Qila-e-Mubarak, or the Auspicious Fort. This magnificent structure, commissioned by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1639 and completed nearly a decade later in 1648, was envisioned as a terrestrial paradise. Situated strategically on the banks of the Yamuna River, it was a sprawling complex adorned with exquisite gardens, opulent palaces, intricate water bodies, and a harmonious blend of mosques and temples. For two centuries, it served as the vibrant capital of the Mughal Empire, a testament to imperial power and artistic brilliance. Interestingly, the fort we recognize today by its distinctive red hue was not originally known as the "Red Fort" until the 19th century. Its initial splendor included a white plaster finish, which, over time, crumbled away, revealing the underlying red sandstone and giving it the popular name "Lal Qila".

To truly understand the pulse of this historic citadel and the lives that unfolded within its formidable walls, one often turns to the compelling narratives crafted by historian Rana Safvi. A distinguished author, translator, and blogger, Safvi is celebrated for her profound dedication to India's rich cultural heritage and diverse civilizational legacy. Her unique approach to history transcends dry academic facts, allowing the stones of the Red Fort to "speak" by populating them with the vivid details of people, their scents, their songs, and their daily sights. This method breathes life into the past, transforming historical accounts into deeply human and relatable experiences.

Safvi's significant contributions include her non-fiction work, "Shahjahanabad: The Living City of Old Delhi," which meticulously describes the fort's magnificence through its surviving buildings. Beyond academic texts, her historical novel, "A Firestorm in Paradise," vividly portrays the inhabitants of the Red Fort on the cusp of the 1857 Uprising, bringing their personal stories to the forefront against a backdrop of monumental change. Crucially, Safvi has also undertaken the vital task of translating pivotal Urdu memoirs, such as those found in "City of My Heart" and "Tears of the Begums". This dedicated work serves a profound purpose. Many English-language historical accounts of Delhi, particularly those written after 1857, were often perceived as dry, dull, or heavily influenced by a British colonial perspective. By focusing on and translating these often-overlooked Urdu sources, Safvi provides a crucial counter-narrative, actively reclaiming and enriching the historical record with indigenous voices and perspectives. Her evocative storytelling, which she believes makes history "far more interesting when a voice, laden with experience and warmth, narrates it" , allows complex historical periods to resonate emotionally with a wider audience. This commitment to documenting the undocumented and bringing buried accounts to public notice is a powerful act of historical restoration, ensuring a more inclusive and authentic understanding of India's multifaceted past.

II. The Imperial Canvas: Architecture as a Reflection of Life

The Red Fort stands as an unparalleled embodiment of Mughal architectural prowess, representing the zenith of their creative genius. Its design is a masterful fusion of Persian, Timurid, Indian, and even European architectural elements, culminating in a style that is both grand and exquisitely refined. The fort's sheer scale is breathtaking, with massive red sandstone walls stretching over two kilometers and towering to heights of up to 33 meters, or between 75 to 108 feet on the city side. Its distinctive octagonal shape, adorned with intricate carvings, precious stone inlays, and precise geometric patterns, speaks volumes of the Mughals' vision of power and prestige. Shah Jahan's ambition for this new capital was immense; the Qila-e-Mubarak was planned to be double the size of the Agra Fort and several times larger than the Lahore Fort, underscoring the emperor's desire for an unparalleled imperial residence.

Beyond its aesthetic grandeur, the Red Fort's architecture was deeply functional, meticulously designed to support the complex daily life and elaborate courtly customs of the Mughal Empire. Every structure within its walls played a specific role in the intricate tapestry of imperial existence.

The Chatta Chowk, for instance, was far more than a mere marketplace; it was India's first covered bazaar, a true novelty in the Mughal era, inspired by a similar market Shah Jahan had admired in Kabul. During its prime, this lavish arcade catered exclusively to the royalty, trading in opulent goods such as gold, silverware, gems, and jewelry, reflecting the luxurious and exclusive aspect of courtly life. Today, much of that original splendor has faded, with shops now dealing in general goods, a poignant reminder of its lost grandeur.

Adjacent to the public spaces was the Naubat Khana, also known as the Naqqar Khana or Drum House. This structure served as the imperial music gallery, where court musicians would announce the emperor's arrival in the Diwan-i-Aam with a flourish of drums. Music was integrated into the very rhythm of court life, with performances occurring daily at specific times to mark the prahars, or three-hour units of the day. Originally adorned with exquisite floral designs, possibly painted in gold, the Naubat Khana’s courtyard was tragically destroyed after the 1857 rebellion, leaving it as an isolated structure today.

The Diwan-i-Aam, or Hall of Public Audience, was the grand stage for the emperor's public interactions. This hall, open on three sides with heavily engraved sandstone arches, was once entirely painted in gold, creating a truly magnificent spectacle. Here, the emperor would hold daily durbar, or public receptions, appearing on a raised marble canopy known as a jharokha. The ceremony was intricate: petitioners would stand on a marble platform inlaid with precious stones, gazing up at the emperor, who was separated from his courtiers by ornate gold and silver railings. Rana Safvi highlights a subtle yet profound detail: the Imam's pulpit at the Jama Masjid, built later, was intentionally constructed at a higher level than the emperor's throne in the Diwan-i-Aam. This architectural choice was a deliberate statement, signifying that while the emperor was "the shadow of the god," he was not a deity himself, a crucial distinction for religious legitimacy. Behind the throne, the famous Orpheus panel, inlaid with multi-colored stones depicting birds and flowers, remains a testament to the fort's exquisite craftsmanship.

The Diwan-i-Khas, or Hall of Private Audience, was arguably the most ornate of the Red Fort's palaces. Constructed entirely of white marble, it was lavishly embellished with intricate carvings, gilt, and fine pietra dura inlay. This exclusive hall served as the venue where the emperor met with his most select courtiers, ministers, and ambassadors to discuss crucial matters of state. At its zenith, Safvi describes it as "the most beautiful building in India".

Connecting many of the private apartments was the Nahr-i-Behisht, or "Stream of Paradise." This continuous water channel flowed through the pavilions, such as the Rang Mahal, emptying into elegant marble basins. This ingenious system provided natural cooling, a welcome respite from the Delhi heat, and enhanced the aesthetic beauty of the imperial quarters. At night, camphor lamps placed in wall niches created an intoxicating, fragrant atmosphere, transforming the living spaces into sensory havens.

The Hammam, or Royal Baths, were private marble bathhouses comprising chambers for hot, warm, and cool baths, complete with integrated heating systems for winter comfort. These were not merely for hygiene; they also served as informal settings where the emperor often engaged in important state discussions with his most trusted courtiers.

Deep within the fort lay the Zenana, or Harem, a world unto itself, comprising royal palaces like the Rang Mahal and Mumtaz Mahal. This was a heavily guarded, exclusively female domain. It housed not only the emperor's wives and concubines but also a vast retinue of female relatives, young princes, dancing girls, thousands of servants, and eunuch guards. Functioning as a self-contained "small city," the Zenana boasted its own markets (including the Meena Bazaar for harem women), laundries, kitchens, playgrounds, schools, baths, and even a treasury for secret documents. Life within these opulent quarters was one of extraordinary luxury, with royal ladies receiving new garments daily, worn once, and then given to their slaves.

The Red Fort's architecture was not merely aesthetic but deeply functional and symbolic. It was meticulously designed to reinforce the Mughal emperor's divine authority while subtly acknowledging religious boundaries, and simultaneously providing practical comforts and spaces for daily life within a self-contained "sovereign city." The elevated throne in the Diwan-i-Aam and the separation by gold and silver railings clearly signified the emperor's exalted status. However, the deliberate choice to build the Imam's pulpit at the Jama Masjid higher than the emperor's throne in the Diwan-i-Aam reveals a sophisticated understanding of power dynamics and religious legitimacy within the Mughal state. This architectural detail demonstrates that even an absolute monarch like Shah Jahan operated within a framework where divine authority, as interpreted by religious scholars, held a higher symbolic position than temporal rule. This was crucial for maintaining the "shadow of the god" narrative without claiming divinity itself, thereby fostering acceptance among a diverse populace. The comprehensive nature of the fort, housing not just palaces but also markets, workshops, and a large population , aligns with the concept of Shahjahanabad as a "sovereign city" or "imperial mansion writ large". This suggests the fort was a meticulously planned microcosm of the empire, where every space, from the public Diwan-i-Aam to the private Hammam , contributed to the projection of power, administrative efficiency, and the luxurious daily life of the ruling elite. The integration of comfort features like the Nahr-i-Behisht within this grand design underscores the Mughal commitment to a holistic, opulent, and functional imperial living.

III. A Day in the Life: Emperor, Courtiers, and the Rhythm of the Court

Life within the Red Fort, particularly for the emperor, was governed by a meticulously choreographed routine, famously described by Sir Thomas Roe, England's Ambassador to the Mughal court, as being "as regular as the clock that strikes the hours". Each day began with a symphony of sounds: as the morning star appeared, the royal orchestra commenced playing music appropriate for the hour, followed by the muezzins' call to prayer from the minarets of the mosques.

A pivotal event of the early morning was the Jharokha-i-Darshan. As the sun ascended, the emperor would appear on the Jasmine Tower, presenting himself to his assembled subjects on the banks of the Yamuna below the palace walls. This practice, adopted by Emperor Akbar, was more than a mere display; it was a direct, face-to-face communication channel, allowing commoners to see their ruler, ascertain his well-being, and present their petitions or grievances. This tradition, with its roots in Hindu custom, fostered a crucial connection between the monarch and his people, serving to legitimize and humanize imperial authority.

After this public appearance, the emperor would retire for prayers and breakfast, preparing for the serious business of state that commenced by mid-morning. The Diwan-i-Aam would become the hub of imperial governance, where cases were heard, and sentences pronounced, often with executioners present to carry out immediate justice. This formal session was interspersed with various entertainments: bands played, jugglers, wrestlers, and acrobats performed, and dancing girls captivated the court. Even exotic animals like lions, tigers, elephants, and rhinoceroses were paraded, creating a spectacle that underscored the empire's wealth and power. This two-hour session would conclude with the emperor's pronouncement of takhlia, and a red curtain drawing across the balcony.

The afternoon brought a shift to more private affairs. The emperor would spend a significant portion of this time with the ladies of the seraglio, attending to matters concerning his vast family. This included settling allowances, pensions, and charitable donations, particularly dowries for girls from impoverished families, with favorite queens and princesses often playing influential roles in these decisions. Occasionally, a second Jharokha-i-Darshan might take place in the late afternoon, sometimes featuring imperial prerogatives such as elephant fights or troop parades. The day would then wind down with evening prayers, dinner, and time spent with family members before the emperor retired for the night.

Courtly protocols and ceremonies were central to the functioning of the Mughal court. Formal gatherings like the Darbar and the more lavish Durbar served as pivotal platforms for conducting state affairs, making crucial announcements, and administering justice. These events were also grand displays of opulence, meticulously designed to impress both local nobles and foreign dignitaries, showcasing the empire's immense wealth and power. Music played an integral role in these proceedings; musicians stationed in the Naubat Khana would play drums five times a day when the emperor was in residence, and thrice when he was traveling, marking the prahars and audibly announcing the emperor's presence and movements within the fort. Imperial processions, often stretching for miles, were eagerly watched by thousands who crowded balconies and rooftops. These elaborate parades featured the emperor's symbols—such as the sun, an upraised hand, or scales of justice—alongside drummers, cavalry, infantry, and even servants who sprinkled water on the roads to suppress dust, all contributing to a magnificent display of imperial might and ceremonial grandeur.

The highly ritualized daily life of the Mughal emperor within the Red Fort was, in essence, a continuous performance of power and governance. This meticulous choreography was designed to project imperial authority, cultivate a direct connection with the populace, and reinforce the imperial cult. The rigid schedule, particularly the Jharokha-i-Darshan, was not merely for administrative efficiency; it was a deliberate ritual to project accessibility and benevolence, fostering loyalty and legitimacy among his subjects. The constant presence of music and grand processions further amplified the imperial aura, creating an immersive experience of power that permeated the fort and the city. This structured daily life ensured that the emperor's authority was not just an abstract concept but a tangible, visible, and auditory presence. It demonstrates how the Mughals skillfully utilized elaborate ceremonies and public displays to reinforce their power and maintain social order across a vast and diverse empire. The entire fort, in this sense, functioned as a meticulously designed stage for this daily imperial drama, where every action, from a morning appearance to a judicial pronouncement, contributed to the stability and grandeur of the realm.

IV. Beyond the Veil: The Vibrant World of the Mughal Harem

The Mughal Harem, often romanticized and misunderstood in Western narratives, was far more than a mere pleasure garden. As Rana Safvi's work illuminates, it was a "sacred or forbidden place," a vast and complex physical space that served as a self-contained "small city" within the Red Fort. This bustling world housed not only the emperor's numerous wives and concubines but also a multitude of female relatives—mothers, sisters, daughters, aunts, and cousins—along with young princes, dancing girls, thousands of servants, and a formidable guard of eunuchs and female warriors known as Urdubegis. Within its precincts were markets, laundries, kitchens, playgrounds, schools, baths, and even a treasury where secret documents and seals were housed, demonstrating its intricate self-sufficiency and organizational complexity.

Daily life within the Zenana was one of extraordinary luxury and varied activity. Royal ladies received new garments every morning, often worn only once before being given to their slaves, a testament to the immense wealth and extravagance of the imperial household. They resided in lavish apartments within structures like the Rang Mahal and Mumtaz Mahal, meticulously crafted with marbles and precious stones, designed to mirror the opulence of heaven. Their days were filled with a diverse range of amusements and pastimes, from the serene act of watching carp with gold rings swim in marble fountains to more dynamic entertainments like elaborate fireworks displays, gazelle fights, pigeon flying, wrestling matches, acrobatic performances, card games, and captivating sessions with musicians, archers, dancing bears, snake charmers, and storytellers. While strict purdah, or seclusion, was observed, women were not entirely confined. They had opportunities to travel for pilgrimages to local shrines, hunting excursions, and sightseeing with the Emperor, always moving in decorated palanquins or atop elephants, ensuring their privacy and status.

Crucially, Rana Safvi's scholarship emphasizes that women within the Harem were an "integral part of court politics". They were not passive figures; matriarchs and influential wives wielded considerable power, often determining the political status of their sons and brothers, securing imperial forgiveness for erring princes, and even acting as significant patrons of the arts, sciences, and architecture. Safvi's nuanced depiction of women in purdah reveals the lively "earthiness of their conversation" that often contrasted sharply with the "extreme decorum" they were expected to observe in public settings. Furthermore, the practice of Kama Sutra arts by accomplished dancing girls within the court points to a more complex and open view of sexuality than is often assumed, highlighting its role in the social fabric and entertainment of the elite.

Rana Safvi's portrayal of the Mughal Harem effectively dismantles the simplistic Orientalist stereotype, revealing it as a sophisticated, influential, and internally dynamic world where women, despite physical restrictions, exercised considerable agency and contributed significantly to the cultural and political life of the empire. The research explicitly states that the harem has often been misrepresented in "Orientalist terms" as a place of "purely sensuous languor" and restricted lives. Safvi's work, however, paints a picture of a "bustling, orchestrated and organised world" with its own internal economy and infrastructure, including markets, schools, and a treasury. This portrayal demonstrates that despite the practice of purdah, women in the harem were not passive. They held a clear hierarchy, engaged in diverse entertainments , and, most importantly, were "an integral part of court politics," influencing decisions and acting as patrons. Safvi's lively depiction of their conversations further humanizes them, allowing readers to connect with their lived experiences. The architectural design of the Zenana, with its luxurious yet protected spaces , facilitated this complex internal world, allowing women to thrive and exert influence within their sphere. This understanding challenges modern assumptions about gender roles in historical contexts, illustrating that power and agency could be exercised in varied forms, even within seemingly restrictive environments. The harem was a vital, albeit veiled, center of Mughal power and culture, demonstrating a sophisticated internal political system that acknowledged and leveraged female influence.

V. A Tapestry of Traditions: Culture, Arts, and Syncretism

The Red Fort, as the heart of Shahjahanabad, was a vibrant crucible where diverse traditions converged, giving rise to the unique cultural phenomenon known as the "Ganga Jamuni Tehzeeb." This concept, a core theme in Rana Safvi's work, describes a deeply interwoven cultural fabric where Hindu and Muslim communities not only co-existed but also co-mingled, creating a rich amalgam of pluralistic life. This was particularly evident in Delhi and within the imperial confines of the Red Fort.

Concrete examples abound, showcasing this cultural blending. Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal ruler, actively participated in both Hindu festivals like Holi, Diwali, Dussehra, and Saloni (Rakhi), alongside major Muslim festivals such as Eid-ul-Fitr, Eid-ul-Zuha, and the Persian New Year, Nauroz. One of the most cherished illustrations of this shared cultural space was the Phoolwaalo'n ki Sair, or the Procession of Flower Sellers. This unique syncretic festival involved a grand procession that would set out from the Red Fort and travel across the city to Mehrauli, symbolizing a communal harmony that transcended religious boundaries. Within the palace itself, both gurus and Sufi sheikhs were venerated, further highlighting the inclusive spiritual environment. The very lineage of the Mughal family, which included Rajput empresses, also contributed significantly to this rich cultural blend, as seen in the mother of Bahadur Shah Zafar being a Rajput.

The Mughal emperors were ardent patrons of the arts, transforming their court into a vibrant cultural and intellectual hub. This patronage led to the flourishing of various art forms:

- Painting: The distinctive Mughal school of miniature painting emerged, characterized by its fine attention to detail, vibrant colors, and exquisite craftsmanship. This style seamlessly blended Persian artistry with Indian themes, depicting scenes from court life, Indian mythology, and intimate portraits of emperors and their families.

- Literature and Language: Persian was adopted as the official court language, which profoundly enriched Indian literature, poetry, and scholarly works. The important practice of translating Hindu scriptures into Persian further promoted intellectual and cultural exchange across different communities.

- Music and Dance: Music and dance were not merely entertainment but essential elements of court life and ceremonial occasions. Classical music, encompassing both vocal and instrumental forms, thrived with instruments like the sitar, tabla, and sarangi. Dance forms such as Kathak evolved into intricate storytelling mediums under imperial patronage.

- Culinary Heritage: Rana Safvi's expertise in food history further illuminates the era's culinary richness. Her contributions to "Desi Delicacies," focusing on dishes like Qorma, Qaliya, and Awadh cuisine, offer a taste of the sophisticated gastronomic traditions that developed within this multicultural environment.

- Gardens: Mughal gardens, heavily influenced by the Persian Charbagh design, were more than just aesthetic landscapes. They were symbolic representations of paradise on earth, meticulously planned with running water channels, reflecting pools, and carefully chosen flora, contributing to both the beauty and comfort of the imperial residences.

Religious tolerance and philosophical approaches were also defining characteristics of the Mughal era. Emperor Akbar's innovative Din-i-Ilahi, a syncretic religion blending elements from various major faiths, exemplified this spirit. Its core principles emphasized "Sulh-i-Kul" (Universal Peace) and ethical living, aiming to foster unity across the diverse empire. More broadly, the Mughals maintained a general policy of religious tolerance and inclusivity, evident in their financial support for religious institutions of all faiths, including Hindu temples and Islamic mosques. They also appointed individuals from diverse religious backgrounds to high-ranking administrative positions, promoting a climate of mutual respect and cultural exchange.

The "Ganga Jamuni Tehzeeb" was not merely a superficial co-existence but a deeply interwoven cultural fabric, where shared celebrations and mutual respect actively shaped the daily lives and identities of the Red Fort's inhabitants. This was a sophisticated and pragmatic model of pluralism that contributed significantly to imperial stability. The emperor's participation in both Hindu and Muslim festivals, along with the prominence of events like Phoolwaalo'n ki Sair, clearly indicates a high degree of inter-religious celebration and interaction within the court and city. Safvi explicitly states that this syncretism was "the norm and not an exception" and a "lived reality". The veneration of gurus and Sufi sheikhs within the palace, and the Rajput lineage of Mughal empresses , illustrate a deep integration rather than mere tolerance. This goes beyond simple cultural blending; it reveals a sophisticated political strategy of inclusion and social cohesion. By actively participating in and promoting diverse cultural and religious practices, the Mughal emperors fostered a sense of shared identity and mutual respect among their subjects. This cultural richness, manifested through art, architecture, and daily life, was a key factor in the empire's stability and prosperity. The Red Fort, as the imperial capital, served as the primary stage for this vibrant demonstration of cultural pluralism, showcasing how diversity could be a source of strength.

VI. The Twilight of an Era: Red Fort's Enduring Legacy

The magnificent life within the Red Fort, a symbol of unparalleled grandeur, faced a dramatic and poignant shift with the failed Mutiny of 1857. This pivotal event marked the twilight of the Mughal Empire, leading to the forced departure of its last emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. In a cruel twist of fate, he exited the fort through the very same river gate that Emperor Shah Jahan had used to enter and celebrate its completion centuries earlier.

The fort then underwent a tragic transformation under British rule. A staggering "more than 80 per cent of the buildings inside the Fort were demolished". This extensive destruction was a deliberate act, aimed at preventing any future rebellions and dismantling the very manifestations of Mughal power. In place of the exquisite palaces and pavilions, barracks were constructed, fundamentally altering the fort's character. While much was lost, Lord Canning's intervention is credited with saving some key structures, including the Diwan-i-Khas, Diwan-i-Aam, and Naubat Khana, from complete obliteration. Furthermore, the fort's physical appearance changed profoundly. Its original white plaster, which had once embellished its red sandstone, fell away over time. This exposed the red stone beneath, leading to its popular and enduring name, "Red Fort" or "Lal Qila," a stark visual reminder of its altered state.

Rana Safvi's empathetic narratives, particularly from her historical novel "A Firestorm in Paradise" and her translations in "Tears of the Begums" and "City of My Heart," vividly convey the profound human impact of the empire's decline. She paints a "tragic and affecting story of a royalty in decline," where once-privileged princes and princesses were reduced to extreme poverty. Heart-wrenching accounts include a daughter of Bahadur Shah Zafar becoming a beggar and a son forced to work as a cart driver. Safvi consistently highlights the "profound and continuing sense of unmitigated loss" that she associates with this period. This loss was not merely political but represented the annihilation of a unique way of life, leading to a shared grief among both Hindus and Muslims, who felt they had lost a paternal figure in the emperor.

The systematic physical destruction and symbolic alteration of the Red Fort by the British after 1857 was a deliberate act of historical and cultural erasure, aimed at dismantling the very manifestations of Mughal power. The British actions, such as demolishing over 80% of the fort's buildings and constructing barracks , were explicitly designed to "prevent another rebellion". This went beyond mere wartime damage; it was a calculated strategy to break the fort's symbolic power and sever the emotional and historical ties of the populace to the former rulers. The change in the fort's popular name, from its auspicious Mughal designation (Qila-e-Mubarak) to a descriptive one (Lal Qila) reflecting its altered state, further solidified this colonial re-appropriation and the erasure of its original grandeur.

Rana Safvi's dedicated work directly confronts this historical erasure. By meticulously translating "untold" Urdu accounts from survivors, including those of royalty reduced to penury , and by crafting historical fiction that brings alive the "minutiae of characters' lives" during the 1857 Uprising , she reconstructs the human dimension of the fort's past. Her emphasis on the "profound and continuing sense of unmitigated loss" acts as a powerful act of cultural memory, ensuring that the "lost way of life" is remembered and understood beyond the simplified narratives of colonial conquest. Her scholarship provides a nuanced, human-centric perspective on a pivotal historical moment, allowing modern readers to understand the complexities and emotional weight of the Mughal Empire's twilight years.

VII. Conclusion: The Red Fort's Timeless Narrative

The Red Fort's journey is a microcosm of India's rich and complex history. From its inception as the magnificent Qila-e-Mubarak, a true "paradise on earth" symbolizing the zenith of Mughal power and artistic achievement, to its eventual decline and transformation into a poignant symbol of resilience and loss, the fort has witnessed centuries of profound change. Within its massive red sandstone walls, a vibrant daily life unfolded, governed by intricate courtly customs. The dynamic and influential world of the harem, far from a mere gilded cage, played a significant role in imperial politics and culture. Most notably, the fort was the epicenter of the "Ganga Jamuni Tehzeeb," a rich, syncretic culture where diverse traditions blended harmoniously, fostering a unique pluralistic way of life.

Historian Rana Safvi's contribution to understanding this monumental heritage is truly invaluable. Her pivotal role in unearthing, translating, and narrating these intricate stories allows modern readers to genuinely experience "life inside the Red Fort" through her eyes. Her unique ability to breathe life into historical stones provides a human-centric and deeply empathetic understanding of its past. Through her dedicated scholarship, the Red Fort remains not merely a collection of ancient buildings but a "living monument to the grandeur and strife of the past", its echoes continuing to resonate through time.

The Red Fort, as illuminated by Safvi's scholarship, serves as a profound and enduring symbol of India's rich, complex, and often poignant history. It stands as a testament to its glorious past, its periods of struggle, and its unyielding spirit, offering a timeless narrative that continues to speak volumes about a bygone era and the vibrant lives that once filled its hallowed grounds.