In the last seven decades, the East Asian countries whose economic development earned them the title of the “Four Asian Tigers” are South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. Among them, South Korea stands out for its rich history, culture, food, entertainment (including the global K-pop industry), tourism, high-tech advancements, K-beauty and cosmetics, and its beautifully structured language known as Hangugeo (한국어).

There was no original native script for speaking or writing Korean until the mid-15th century, when a revolutionary step was taken by King Sejong the Great of Korea. In 1443, he invented the Korean script now known as Hangeul (한글).

Han (한) means “great”

Geul (글) means “letters”

In South Korea, the script is called Hangeul (한글), while in North Korea, it is known as Chosŏn'gŭl (조선글).

Every year on October 9, South Korea celebrates Hangeul Day (한글날, Hangeul-nal)—where “날” means “day”—commemorating the creation and proclamation of this scientific writing system.

At the National Hangeul Museum in Seoul, one can view the most precious document in Korean linguistic history:

Hunminjeongeum Haerye (훈민정음 해례), translated as “Explanations and Examples of the Correct Sounds to Instruct the People.”

It was published in 1446, explaining in detail how Hangeul was created.

The museum also preserves the first song written in Hangeul (1447) and the first-ever newspaper printed in Hangeul in the early 1900s.

During Japanese colonial rule, despite severe suppression, Koreans bravely published newspapers, literature, poetry, and pamphlets using Hangeul to resist cultural erasure and preserve their identity.

Why Hangeul Was Created

Before the invention of Hangeul, only nobles and scholars had access to education and used Classical Chinese characters, known as Hanja (한자) in Korean and Kanji in Japanese.

King Sejong the Great observed that due to the complex stroke order, pronunciation difficulties, and inaccessibility of Chinese characters, commoners struggled to learn and express themselves. To promote mass literacy, he designed a logical, simple, and phonetic script.

He scientifically studied the articulatory phonetics of the Korean language—how the lips, teeth, tongue, glottis, and palate work—while designing the consonants.

Moreover, the consonants symbolised the five major elements of the universe: fire, water, metal, wood, and soil. The goal was to make the characters simple and accessible for all social classes.

Originally, Hangeul consisted of 28 basic letters, but over time, some characters fell out of use, resulting in the modern-day script used today.

Uniqueness and Global Relevance

Out of over 3,000 major languages and around 7,000 minor languages in the world, Korean ranks 13th in terms of the number of native speakers—approximately 77 million native speakers and 5.6 million heritage speakers (numbers may vary slightly).

Many languages have vanished because they lacked a written script, leading to their extinction. But Korean has preserved itself through its unique, scientifically developed script.

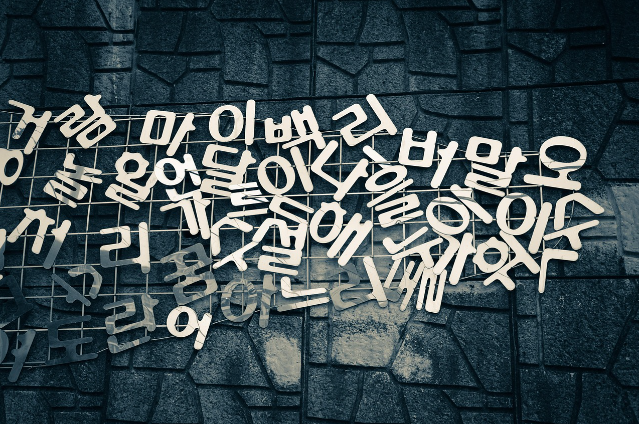

A key feature of Hangeul is its syllable block structure. Korean is written horizontally from left to right and vertically from top to bottom, and the letters are grouped into blocks that represent syllables—making it one of the most structured, elegant, and efficient writing systems in the world.

Philosophical and Scientific Aspects

The vowels in Korean are based on Chinese metaphysical principles and represent the three fundamental elements of the universe:

Dot (ㆍ) for the Sun/Heaven

Horizontal line (–) for the Earth (Yin)

Vertical line (|) for Human (Yang)

This cosmic and philosophical base reflects King Sejong’s intention to harmonize science, society, and philosophy in a script.

Linguistic Roots and Historical Influence

Some scholars argue that Korean may have a distant relationship with Proto-Korean and Proto-Japonic languages due to similarities in structure, vocabulary, and grammar. However, this theory remains unconfirmed.

Korean has also been influenced by Chinese and Japanese vocabulary over the centuries. This is why early official records were mostly written in Hanja for scholarly and government purposes.

Historical Stages of the Korean Language

1. Old Korean (up to 10th century)

Used during the Three Kingdoms Period (Goguryeo, Baekje, Silla) and early Unified Silla.

Each kingdom had its own variant:

Goguryeo language

Baekje language

Silla language

Since Silla unified the Korean Peninsula and left the most records, its dialect is the main reference for Old Korean. At this stage, no native writing system existed.

2. Middle Korean (10th – 16th century)

This era marked a major linguistic breakthrough.

Hangeul was created by King Sejong and the Hall of Worthies (집현전).

It aimed to replace Chinese characters and promote literacy among commoners.

“The sounds of our language are different from those of China, and so our characters do not match. Hence, many of our people, though they want to read and write, cannot express themselves. I am saddened by this, so I have created 28 new letters…”

— King Sejong, Hunminjeongeum Haerye

Modern Korean spelling rules, pronunciation systems, and historical dictionaries are derived from this period.

3. Modern Korean (17th century – Present)

After liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, Hangeul became Korea’s official national script.

Though once considered a “low-class” or “women’s script,” Hangeul is now the medium of education, government, literature, and media in South Korea.

Hanja is still occasionally taught, especially in academic or legal settings, but is rarely used in everyday life.

Final Thoughts

A language cannot survive intellectually or spiritually if it ceases to exist physically. Without language, knowledge cannot be preserved or exchanged.

From replacing Classical Chinese to the creation, preservation, and promotion of Hangeul—the journey of the Korean language is one of courage, logic, and cultural resilience.

Apart from this, the rise and spread of Korean culture along with its language learners is captivating, showing its soft power dominance over the international community. The more the language is learned, the more people feel connected to its roots and culture.