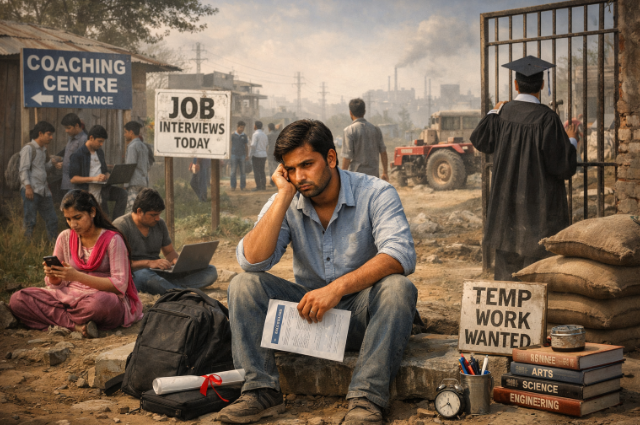

“He did everything right—and still ended up nowhere.”

Ravi (name changed) is 24. He holds a bachelor’s degree, a neatly printed résumé, and a quiet sense of defeat. His mornings begin with job portals and end with silence. Interviews are rare. Replies are rarer. At home, the question hangs in the air like dust: “So, what next?”

This is not Ravi’s story alone. It is the story of millions of educated young people in India who were promised destinations—but handed detours instead.

For decades, education was sold as the safest investment. Study hard. Get a degree. Secure a job. That promise is now cracking. Colleges are producing graduates faster than the economy can absorb them. Classrooms are full, but pathways are missing. Degrees are earned, yet dignity remains delayed.

Recent surveys repeatedly show a hard truth: young graduates face some of the highest unemployment and underemployment rates in the country. Many are not jobless because they lack effort, but because the system offers them limited, mismatched, or unstable opportunities. Arts graduates compete in a market that undervalues their skills. Science graduates are told they need “experience” before their first job. Professional degree holders drift into work unrelated to what they studied.

Unemployment here is not just about money—it is about time lost, confidence eroded, and futures put on hold. Families make sacrifices. Students carry expectations. When jobs don’t arrive, silence replaces celebration.

This crisis remains largely invisible because it unfolds quietly—in shared rooms, in exam halls turned waiting rooms, in homes where educated youth hesitate to speak about failure. It is easier to blame individuals than to question systems.

This article looks beyond statistics to examine a deeper reality: how a growing gap between education and employment is reshaping the lives, mental health, and hopes of India’s educated youth.

Not as a complaint—but as a necessary reckoning.

Here’s a specific, data-rich, human-tone section for “II. The Scale of the Crisis” — framed like a narrative you’d place in your article:

The Scale of the Crisis | When Numbers Start Talking

The story of educated unemployment in India only gains gravity when we listen to the numbers. According to international labor reports, youth with a graduate or higher degree face a much higher unemployment rate than those with less education — nearly 29 % among college graduates compared with just 3–4 % for those without formal schooling.

It feels counterintuitive: more education should open doors, not close them. Yet the data paints a stark picture of a paradox where education no longer guarantees employment — it sometimes seems to increase the odds of being without dignified work.

This gap is further highlighted by differing surveys on employability. Reports like the India Skills Report find that only about half of graduates are considered employable when measured against market relevance and skill standards — meaning millions enter the job market with degrees that don’t match employer expectations.

India’s broader unemployment figures also hint at deeper fissures. National labour force data shows overall unemployment around 5.6 %, but urban youth (ages 15–29) continue to experience much higher rates — often above 15 % and even close to 19 % in some months.

What these figures fail to capture fully is underemployment — the silent dimension where educated youth work in low-skill roles that neither reflect their qualifications nor provide stability. Many graduates take up gig work, contract jobs, or part-time roles simply to survive, while meaningful, stable careers remain elusive.

When we break these trends down further, we see different pressures by discipline and geography:

Graduates in arts and humanities often struggle more than those in tech or professional fields, not just for job slots but for roles that value their training.

Science and technical graduates may find roles, but often in unrelated sectors or at wages that undercut their investment in education.

Across urban centers, competition is fierce, and opportunities are limited; in semi-urban and rural regions, jobs that match degree-level skills are rare or non-existent.

In this landscape, unemployment stops being a mere statistic — it becomes a lived reality of qualified individuals waiting for work that matches their training, aspirations, and dignity.

Inside the Classroom | Degrees That Don’t Translate

Step inside many college classrooms in India, and a quiet disconnect becomes visible. The syllabus often belongs to another decade, while the job market moves at digital speed. Students memorize theories, definitions, and long answers—but rarely learn how to apply them outside the exam hall. Rote learning dominates. Critical thinking struggles to breathe.

Degrees are completed, but skills remain incomplete.

Course content stays heavily theoretical, with little exposure to real-world problems, tools, or workplace practices. What students study and what employers demand live in parallel universes that rarely meet.

Industry linkage exists mostly on paper. Internships, when offered, are frequently unpaid, short-term, and symbolic. They fill certificates, not skill gaps. Many students spend weeks “interning” without learning a single practical tool or gaining meaningful mentorship. There is no pipeline—only a placeholder.

Then come the silent gaps that students rarely admit openly.

The language gap: English dominates interviews and workplaces, but many graduates are never trained to speak, present, or write with confidence.

The digital gap: Basic software, data handling, or platform literacy is assumed—yet rarely taught.

The confidence gap: Years of exam-oriented education leave students unsure how to think independently, communicate clearly, or sell their own abilities.

One final-year student from a government college summed it up quietly:

“I have marks, but I don’t know how to explain what I can actually do.”

Another graduate preparing for competitive exams said:

“They taught us answers, not skills. Outside the exam hall, I feel unprepared.”

These are not failures of effort. They are failures of design.

Classrooms continue to produce degrees that look strong on paper but translate poorly in practice. Until education aligns with reality, graduates will keep stepping out of colleges with certificates in hand—and uncertainty ahead.

The Exam Trap | Competitive Culture Without Capacity

For many educated youth in India, unemployment does not lead to exploration—it leads to a single narrow tunnel: competitive exams. Government jobs, public sector posts, and a handful of elite entry points are seen as the safest exits from uncertainty. When the private job market feels unstable, exams become the last promise of security.

This overreliance has created a dangerous funnel. Millions compete for a few thousand seats. The odds shrink each year, but the hope refuses to die. Graduates spend years preparing—one exam cycle bleeding into another—often postponing work, income, and adulthood itself. What begins as a one-year plan quietly turns into three, five, sometimes seven years of waiting.

Here, coaching centres step in—not as educators, but as industries. They sell structure, certainty, and success stories. Preparation becomes a product. Aspiration becomes a business model. For many students, coaching replaces college as the real classroom. Yet outcomes remain brutally unequal: a few succeed, most repeat, and many silently exit.

The emotional cost is heavy and cumulative.

Burnout becomes normal. Anxiety becomes routine. Friendships thin out. Family pressure intensifies. Life milestones—jobs, marriage, independence—are indefinitely delayed. A generation remains academically qualified but socially paused.

One aspirant puts it simply: “I am not unemployed. I am preparing.”

But preparation, stretched too long, becomes another form of unemployment—one without income, identity, or closure.

This is not a competition without effort. It is a competition without capacity.

A system that funnels millions into the same narrow exits, without expanding opportunities elsewhere, does not reward merit—it exhausts it.

Class, Caste, and Capital | Unequal Starting Lines

The unemployment crisis does not begin at the job interview—it begins much earlier, at the starting line. In India, not all graduates enter the race with the same resources, even if they hold the same degree. Class, caste, and capital quietly shape outcomes long before merit is tested.

For first-generation graduates, a degree is not just a qualification—it is a leap into the unknown. They carry family expectations without family guidance. There are no alumni networks at home, no professional vocabulary at the dinner table, no safety net if things go wrong. Failure is costly, not experimental.

In contrast, privilege-backed peers often arrive buffered by invisible advantages. Networking works as silent currency. A recommendation, an internship lead, or even casual exposure to professional spaces can open doors that remain closed to others. These connections rarely appear on résumés, yet they decide outcomes.

Language deepens the divide. English fluency is treated as intelligence, and confidence as competence. Students from urban, English-medium backgrounds navigate interviews with ease, while equally capable graduates hesitate—not because they lack knowledge, but because they lack polish. The workplace rewards familiarity, not just skill.

Financial capital further tilts the field. Those with economic security can afford unpaid internships, exam retakes, relocation, and long job searches. Those without it must choose survival over strategy. A temporary job becomes permanent not by choice, but by necessity.

In this unequal landscape, “merit” often becomes a comforting myth. It hides the structural head start some possess and the structural barriers others must climb. Success appears individual, while disadvantage remains collective and invisible.

The crisis, then, is not just about jobs—it is about who gets time, space, and permission to fail before they succeed.

The Psychological Fallout | When Waiting Becomes Identity

Unemployment does not end with the absence of work. It lingers, stretches, and slowly reshapes the mind. For many educated youth in India, prolonged waiting becomes more than a phase—it becomes an identity.

Months without work quietly turn into years. With time, confidence erodes. Days lose structure. Self-worth begins to depend on email inboxes and interview calls that rarely arrive. What starts as patience slowly hardens into self-doubt. The question shifts from “When will I get a job?” to “What is wrong with me?”

Shame deepens the silence. At family gatherings, conversations shrink. Neighbours ask questions with forced concern. Parents carry anxiety they cannot express, while graduates absorb guilt they do not deserve. Failure is personalized, even when the system is at fault. Many choose quiet endurance over open conversation.

The digital world makes this burden heavier. On platforms like LinkedIn, success is curated and constant. Promotion announcements, new job titles, and smiling profile photos flood timelines. Comparison becomes unavoidable. Behind the screen, waiting feels lonelier, slower, and more humiliating.

What remains most damaging is the stigma. Speaking openly about unemployment is still seen as a weakness. Mental health struggles are dismissed as a lack of effort or resilience. Burnout is normalized. Anxiety is minimized. Asking for help feels like admitting defeat.

In this climate, educated unemployment is not just an economic issue—it is a psychological one. When waiting becomes identity, hope turns fragile, and silence becomes survival.

Coping Strategies | Survival, Not Success

When stable employment stays out of reach, educated youth in India do not stop working—they adapt. What emerges, however, is not a story of success, but one of survival.

Freelancing, gig work, and short-term contracts become the most accessible options. Content writing, delivery work, online tutoring, data tagging, and customer support—jobs unrelated to years of study fill the gap left by absent opportunities. These roles offer quick income, not long-term growth. They pay bills, not ambitions.

Over time, overqualification turns into quiet erosion. Degrees lose relevance. Skills go unused. Professional identity weakens. Many graduates stop introducing themselves by what they studied and start defining themselves by what they do “for now.” Temporary becomes permanent without intention.

Migration appears as another coping route. Some move physically—to metros, industrial hubs, or overseas—chasing possibilities. Others migrate digitally, entering global gig platforms where work is unstable but accessible. Distance replaces belonging, and flexibility replaces security.

Families often celebrate these shifts as resilience. Society calls it hustle. But beneath the praise lies a harder truth. Is this adaptation empowering—or is it resignation disguised as strength?

When educated youth settle for less, not by choice but by exhaustion, coping becomes compliance. Survival keeps people afloat, but it does not move them forward.

Policy vs Reality | Where the Gap Widens

On paper, the response to educated unemployment in India looks ambitious. Skill missions, employability schemes, and startup incentives—policies promise to bridge the gap between education and work. The intent appears strong. The outcomes remain weak.

Most employability programmes focus on certification rather than placement. Students complete short-term courses, collect badges, and receive training certificates—but jobs rarely follow. Skill is measured by attendance, not absorption. The result is a growing pile of credentials with limited market value.

Implementation gaps widen the divide. Many schemes are urban-centric, digitally dependent, and poorly communicated. Youth from semi-urban and rural areas often remain unaware, under-supported, or excluded. Infrastructure exists unevenly; opportunity does not travel equally.

Employers, meanwhile, shift responsibility outward. Entry-level roles routinely demand “prior experience, even from fresh graduates. Internships replace jobs, contracts replace careers. Risk is transferred downward, onto individuals least equipped to carry it.

- This creates an accountability vacuum.

- Universities blame the industry.

- Industry blames skill gaps.

- The state blames employability.

- Graduates absorb the cost.

No single institution owns the failure. Coordination between education systems, policymakers, and employers remains fragile. Until accountability becomes collective, solutions will remain fragmented.

The gap between policy and reality is not about lack of ideas—it is about lack of execution, ownership, and alignment. And in that gap, educated youth continue to wait.

Reimagining the Path | What Actually Needs to Change

Fixing educated unemployment in India does not require more slogans—it requires structural honesty. The problem is not that students refuse to work; it is that systems refuse to evolve. Real change begins inside institutions, not advertisements.

First, curriculum reform must move faster than the job market, not years behind it. Courses need regular updates, practical components, and exposure to real tools, case studies, and problem-solving. Education must teach how to think and apply, not just what to remember.

Second, paid internships and apprenticeships must become the norm, not a privilege. Work experience cannot be extracted for free. When internships are unpaid, only the financially secure can afford them. Fair pay is not charity—it is access, dignity, and skill-building combined.

Third, career guidance cells need to function as active bridges, not decorative offices. Students require early exposure to career options, mentorship, resume-building, interview training, and realistic pathways beyond exams. Guidance should start in classrooms, not after graduation.

Finally, the obsession with STEM optics must be questioned. Arts, humanities, and interdisciplinary skills are not liabilities—they are assets. Communication, ethics, critical thinking, cultural understanding, and adaptability are essential in a changing economy. A balanced workforce cannot be built on one stream alone.

Reimagining the path means accepting a simple truth: education must lead somewhere. When systems align learning with life, degrees can once again open doors instead of extending waiting lines.

Redefining Success Beyond the Degree

Ravi is still searching. Not because he lacks effort, intelligence, or discipline—but because the road ahead remains poorly mapped. His degree did not fail him; the system surrounding that degree did. Like millions of educated youth in India, he stands ready, trained, and hopeful—yet paused by forces beyond his control.

This is the central truth of the crisis. Education is not the problem. Misalignment is. When classrooms teach in isolation, policies operate without coordination, and employers demand readiness without offering entry, graduates are left stranded between promise and possibility.

Success, then, must be redefined. Not as a narrow list of elite jobs or exam ranks, but as meaningful, stable, and dignified work that values learning across disciplines and backgrounds. A degree should mark the beginning of contribution—not the start of waiting.

The solution lies not in lowering aspirations, but in rebuilding pathways. When education connects with opportunity, when systems share responsibility, and when youth are trusted rather than tested endlessly, momentum returns.

Degrees must become doorways again—not waiting rooms.

Only then can education reclaim its purpose: not to delay life, but to launch it.