Introduction: The Erased Legacy

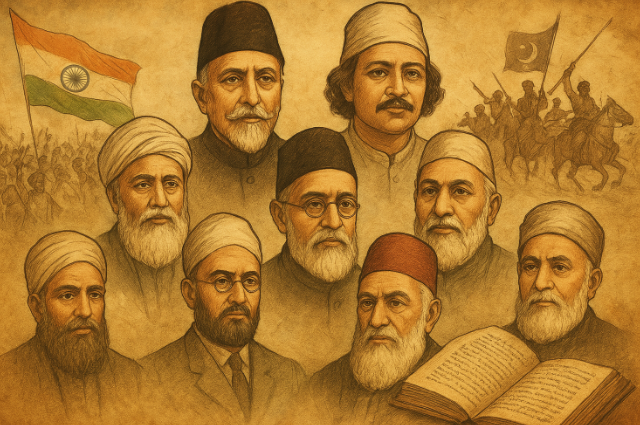

India’s freedom struggle is a tapestry woven from the sacrifices of countless individuals—yet, the role of Muslim scholars and freedom fighters has often been obscured or selectively underrepresented in mainstream historical narratives. In recent years, anti-religious and communal sentiments have led to the marginalization of the immense contributions made by Muslim intellectuals, revolutionaries, and theologians who, driven by both religious conviction and national duty, stood up against colonial oppression.

While the likes of Gandhi, Nehru, and Patel are rightly remembered, Muslim scholars like Maulana Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi, Shah Abdul Aziz, and Zainuddin Makhdoom al-Kabir have been reduced to footnotes—if mentioned at all. This article revisits and analyzes the legacy of eight eminent Muslim scholars, from both North and South India, who made enduring contributions to India’s independence movements, ranging from armed revolts to ideological awakenings and literary resistance. Their stories offer not only a more inclusive narrative but a corrective to the prevailing amnesia around India’s pluralist and anti-colonial past.

Some of the Scholars and Their Roles...

1. Shah Abdul Aziz Dehlavi (1746–1824, Delhi)

Son of the illustrious Shah Waliullah, Shah Abdul Aziz was a renowned Islamic jurist and scholar who courageously declared British rule in India as un-Islamic in 1803—a theological fatwa that laid the foundation for Muslim resistance against the British. He issued this pronouncement during a period of rapid East India Company expansion, particularly after their consolidation of power in Delhi. Shah Abdul Aziz's fatwa did not merely stay within the bounds of religious edicts—it became a political manifesto that inspired the first waves of anti-colonial sentiment among Indian Muslims.

Through his writings and teachings at Madrasa Rahimiya, Shah Abdul Aziz laid the groundwork for political consciousness among Indian Muslims. His emphasis on active resistance against foreign occupation influenced generations of scholars and revolutionaries. Notably, his students and followers—such as Syed Ahmad Barelvi and Shah Ismail Shaheed—later played pivotal roles in uprisings across North India. Despite British surveillance and repression, Shah Abdul Aziz’s ideological defiance sowed seeds of rebellion that would bloom during the Revolt of 1857 and beyond.

2. Maulana Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi (1797–1861, Khairabad, Uttar Pradesh)

A philosopher, poet, and scholar par excellence, Maulana Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi was a towering intellectual force in 19th-century India. Born in Khairabad, UP, he served as a teacher of Arabic and Persian under the British East India Company. However, when the Revolt of 1857 broke out, he joined the resistance in full force. He was instrumental in issuing a fatwa of jihad against British colonial rule, rallying Muslim scholars and commoners alike to rise in defense of their faith and homeland.

Unlike many who limited themselves to verbal opposition, Khairabadi took part in military campaigns in Delhi and Awadh, aligning with rebel leaders like Bahadur Shah Zafar. His role was not confined to ideological mobilization—he actively participated in military planning and arms organization. Arrested by the British in 1859, he was tried and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Andaman Islands. There, in the infamous Cellular Jail, he composed deeply moving poetry and theological treatises before dying in 1861.

His bravery and sacrifice highlight the intellectual as well as physical resistance offered by Indian Muslims, often paid with life, exile, or death in prison.

3. Zainuddin Makhdoom al-Kabir (c. 1465–c. 1522, Ponnani, Kerala)

Long before British colonialism took hold, Kerala’s Malabar coast faced the brutal expansion of Portuguese imperialism. Zainuddin Makhdoom al-Kabir, a Sunni Shafi’i scholar from Ponnani, Kerala, emerged as one of the earliest figures to combine Islamic scholarship with anti-colonial resistance. Born around 1465, Makhdoom studied in Makkah and returned to India to establish a madrasah in Ponnani—then known as the “Little Makkah” of the Malabar.

His seminal Arabic work "Tuhfat al-Mujahidin", written around 1520, is considered the earliest anti-colonial historical text in India, documenting the atrocities committed by the Portuguese and calling for organized jihad. Makhdoom emphasized the need for unity among Muslims and Hindus in resisting European invaders, warning that imperialism threatened not just religious values but indigenous sovereignty.

Though he passed away around 1522, his intellectual legacy lived on through the next generation of Makhdooms and Muslim rulers of Malabar who resisted colonial encroachment. His writings laid the foundation for a southern Indian tradition of Islamic resistance, predating the 19th-century uprisings of North India.

4. Maulana Qasim Nanautawi (1832–1880, Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh)

Founder of Darul Uloom Deoband, Maulana Qasim Nanautawi, emerged from the embers of the 1857 rebellion with a vision for intellectual and spiritual resistance. Born in Saharanpur in 1832, he was deeply influenced by the revolt and even participated in the Battle of Shamli against British forces. Although the military resistance was crushed, Nanautawi understood the need to preserve Islamic identity and knowledge through education.

In 1866, he established Darul Uloom Deoband, which became the cradle of religious scholarship and resistance. The madrasa provided Islamic education independent of British interference and encouraged students to resist colonial cultural imposition. Nanautawi’s vision was not merely scholastic—it was strategic resistance by nurturing future generations of freedom-conscious Muslims.

His emphasis on self-reliance, anti-imperial education, and spiritual revival inspired movements across India, and Deoband alumni played key roles in later freedom struggles, especially during the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements.

5. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (1817–1898, Delhi/Aligarh, UP)

Though often seen as an educationist and reformer rather than a revolutionary, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s contributions to Indian independence lie in his strategic foresight. Born in Delhi in 1817, he served as a judicial officer under British rule but was deeply shaken by the events of 1857, during which he witnessed the brutalities inflicted upon both Muslims and Hindus.

Recognizing that intellectual empowerment was the key to future resistance, he founded the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligarh in 1875, which later became Aligarh Muslim University. Sir Syed urged Muslims to pursue modern sciences and Western education while preserving Islamic values, aiming to uplift the community that had been politically marginalized after 1857.

Although he believed in reconciliation with the British as a short-term necessity, his long-term vision fostered a politically conscious, educated Muslim middle class that would eventually question colonial rule. His legacy laid the groundwork for intellectual dissent and reform movements among Indian Muslims.

6. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (1888–1958, Mecca-Calcutta)

Born in Mecca but raised in Calcutta, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was one of the most brilliant intellectuals and nationalists India ever produced. A polyglot, scholar of Quranic sciences, and newspaper editor, Azad emerged as a key figure in the Khilafat Movement (1919–1924), which aimed to protect the Ottoman Caliphate and oppose British imperialism.

Azad edited Urdu journals like Al-Hilal and Al-Balagh, which became platforms for anti-colonial thought and Hindu-Muslim unity. Despite multiple arrests, he remained a vocal supporter of complete independence (Purna Swaraj) and joined Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement. In 1923, he became the youngest President of the Indian National Congress.

Unlike many contemporaries, Azad envisioned a pluralistic India rooted in secularism and unity. After independence, he became India’s first Minister of Education, emphasizing universal education and scientific temper. His deep Islamic knowledge, coupled with political activism, made him a bridge between faith and nationalism.

7. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890–1988, Utmanzai, NWFP – now Pakistan)

Known as the “Frontier Gandhi”, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan was a devout Muslim and an ardent advocate of nonviolent resistance. Born in Utmanzai (now in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan) in 1890, he founded the Khudai Khidmatgar (Servants of God) movement in 1929, a peaceful volunteer force of Pathans who protested British rule through civil disobedience.

A close associate of Mahatma Gandhi, Ghaffar Khan believed that Islam inherently promoted peace and justice. His activism directly challenged the colonial narrative that associated Muslims with violence. Under his leadership, tens of thousands of Pashtuns adopted nonviolent protest tactics, despite brutal repression by British authorities.

He opposed the partition of India, warning it would lead to communal bloodshed—a prophecy that sadly came true. Though marginalized post-1947 in Pakistan, his role in India’s freedom movement stands as a powerful testament to the compatibility of Islam and nonviolence.

8. Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899–1976, Churulia, Bengal)

Known as the “Rebel Poet” (Bidrohi Kobi), Kazi Nazrul Islam was not just a poet but a revolutionary spirit who fought colonial injustice through his pen. Born in 1899 in Churulia, West Bengal, Nazrul’s early life was marked by poverty, but he soon rose as a literary genius writing in Bengali and Urdu.

His poetry collections like "Agniveena" and essays in “Dhumketu” (The Comet) inspired the masses to revolt against British tyranny. He was arrested in 1923 for “sedition” and imprisoned for his fiery verses that advocated freedom, equality, and Hindu-Muslim unity. While in jail, he composed some of his most defiant works, including “Rajbandir Jabanbandi” (The Political Prisoner’s Testimony).

Nazrul’s contribution lies in his ability to emotionally galvanize the masses. He infused Islamic spiritualism with revolutionary zeal, creating a cross-religious appeal that united communities in the struggle against colonialism. Today, he is celebrated as Bangladesh’s national poet, but his role in India’s freedom struggle deserves equal remembrance.

Conclusion: Setting the Record Straight

From Delhi to Deoband, Bengal to the Malabar, the contribution of Muslim scholars to India’s independence was not peripheral—it was foundational. These scholars did not merely preach from pulpits or write in isolation; they fought, organized, resisted, educated, and inspired. Their legacy is a testimony to the inclusive, multi-religious character of India’s freedom movement—an aspect often undermined by communal narratives today.

The erasure or minimization of these voices in mainstream history is not just academic injustice—it is a distortion of India’s pluralist heritage. At a time when identity politics seeks to divide, remembering these scholars becomes an act of resistance itself. Their courage, intellect, and sacrifices remind us that Indian nationalism was—and must remain—a shared dream.