Introduction

The division of British India in August 1947 along religious lines into the independent states of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan sparked one of the largest mass migrations with at least 10 million people on the move accompanied by unimaginable violence on all sides.

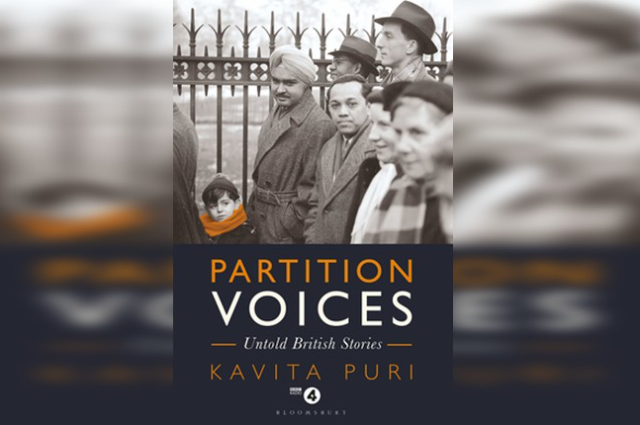

Puri’s book begins with the cremation of her father who was born in Lahore, spent the majority of his lifetime in Britain and finally resting along the most sacred and blessed river in India. Puri, an award-winning BBC journalist recorded testimonies from across Britain of colonial British and British South Asians who were a part of the 1947 partition. After decades of silence, Puri gives voices to those by creating a space for them to tell their stories, in the way that they remember them. This story is not merely a documentation of facts but also personal, stemming from her family’s experiences. She narrates the story of the refugees who fled across the Radcliffe Line, and then further ahead, to Britain. The people who were oppressed by the British have now come to the land of the English.

The desire to remember and preserve their homeland. So many memories interspersed with grief and shame have lapsed into silence and were passed down to subsequent generations which finally has been spanned out into twenty-three chapters divided into three parts: End of Empire, Partition, and Legacy narrating the twin notions of homeland and belonging.

These stories aren’t from lands far away. It has direct relevance to British citizens, once subjects of the British Raj. Scattered around homes in Britain are some of those who, like Puri’s father, witnessed the traumatic birth of two nations and who subsequently migrated to post-war Britain. Yet their partition story is barely known. Just like that, so many survivors now live in Britain who have kept quiet for decades about their experiences. They are only beginning to speak about what they witnessed seventy years ago.

Cultural and Historical Context after Partition:

At the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, India and Pakistan officially gained their independence and became dominions with the British Commonwealth. Astonishingly, millions of people had no idea at the moment of freedom whether they were in India or Pakistan, as the boundary lines in the provinces of Bengal and Punjab had not been made public yet. Sir Cyril Radcliffe, the British lawyer was given the task of establishing the boundary line which is ironic as he had never previously been to India and was given just forty days to decide on the border. The two states were divided broadly along religious lines. Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east were split into two according to their Muslim and non-Muslim majority areas.

Intricately entwined communities were to become forever ripped apart. The intensity of this unpicking had been catastrophically underestimated by the new governments and the colonial authorities. The numbers killed in partition violence will never be known. Many historians have estimated it to be between half a million and a million. Partition violence was more intense and sadistic than anything that had proceeded it. Tens of thousands of women and girls are believed to have been raped and abducted and finally, the violence reached a level where paramilitary troops had to be brought in.

Violence differed across northern India in its intensity but also its timing. The term “Long Partition” was coined by Vazira Zamindar to explain the lasting impression of this devastating event. It is estimated that between 10 and 12 million people migrated at the time of partition. Millions had no choice but to move as they found themselves on the wrong side of the border. This movement of people transformed the new states as well as individuals. Cosmopolitan cities such as Delhi, Bombay, Karachi, Amritsar, and Lahore lost their citizens and were shaped by the influx of refugees. Rioters wreaked havoc in many cities. Riot zones were declared. This social dislocation of partition in areas beyond Punjab and Bengal generated individual economic crises, refugee upheavals, and visible destruction in every area affected. The existence of communities that had lived together for centuries, with a shared language and culture, can only now be learned of in history books.

Modern Britain has been transformed by the South Asian population with over three million people in England and Wales with South Asian heritage. It is estimated that around eight thousand Indians lived in Britain on the eve of partition. The areas of India and Pakistan that were disturbed by partition and its aftermath were major contributors to this emigrant flow to Britain. Many people migrated from both Indian and Pakistani Punjab in the years immediately after the war.

Clair Wills, in her book Lovers and Strangers: An Immigrant History of Post-War Britain, observes that the villages of Sylhet and Punjab were linked in an imaginary geography not to Dhaka or Delhi, but to London, Birmingham, Leicester, and Bradford. Usually, at least one member of the family would migrate. And nearly all who came to post-war Britain were young, single males, who sent remittances home to their extended family. They never imagined they would permanently settle in Britain for good.

Their destinations in Britain were largely confined to metropolitan areas- places like Bradford, Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Oldham, Southall, and Luton- through chain migration, so there was already a network of circulation, even if it was in small numbers. In Britain, they were all seen as Asians, unlike on the Indian subcontinent where their religious, regional and other differences were so pronounced. They worked together in those early days, fighting for workers’ rights, and in the later years, against racism.

There was an increasing discomfort because of the number of immigrants in the country followed by the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act because of which the first of many restrictions began to be placed. This legislation had the unintended consequence of increasing the number of those migrating from the Indian subcontinent- people came over in a rush to beat the ban. It also meant that the people who thought they were coming to stay for a few years chose to stay back out of fear that they would not be able to come back to Britain if they left. But crucially, it also meant that wives and children began to arrive in Britain, as there was concern that they may not be allowed to join their men after the legislation was in force. These pioneers looked like a more permanent presence on the landscape, and they were laying down their roots.

The story of Partition is also the story of Britain, not just in the formal sense of history. Instead, it is the history of the people. These stories throw light on how political decisions alter their lives completely, not just in the moment but long after the event has passed. “As a refugee, even if you cannot live in your “home” country, that sense of belonging never leaves you”, says Puri in an interview. The connection one has to one’s land persists through generations. This is not only the story of refugees following the Partition but of anyone who has ever been displaced. It also adequately explains the migration flows to post-war Britain and the reason why the country looks the way it does after being shaped by its British South Asian compatriots.

Memory and Spatial Representation:

“Partition, though filled with horror in so many ways, is also a story about love. Love of your land. A land that was lived on for centuries by a family's ancestors, where traditions and cultures, even language were shared, a time where religious differences were mostly tolerated.” (Puri, 12)

She writes about a Hindu interviewee, originally from Karachi who was forced to flee from India, who told her that when he returned for a visit, decades later, he took dust from the ground, kissed it, and touched it to his forehead. This very simple act made him feel like he was returning to his mother, whom he had not seen for a very long time.

Some of the people whose homes Puri visited were lucky enough to have kept physical mementos from their childhood days in British India. It included stones from the lands of their home, jars containing dust from their motherlands, and sometimes a brick from their home. It was all they had left.

It is one of the centuries of coexistence shattered, homes left hurriedly, and after all, a story of traumatic loss. Not just a loss of a house or possessions but a loss more profound. Loss of a homeland. A grief that is tangible seventy years on.

There has been silence not only in Britain but also in India and Pakistan even though the reasons are slightly different. Many who came to the UK in the years after partition were just getting on with their lives, fighting different battles to be accepted in the new country. There was no time to dwell on the past. And, unlike back home, they were fighting together whether it was to improve their working lives or in the fight against racism. In Britain, they were all lumped together as Asians. Their children and grandchildren knew little of life back home which is why they did not speak about it as well.

There was an institutionalized silence too- no one talks about partition. There are no memorials or museums in Britain. Few people talked about the end of the Empire or even the Empire, so there was no open, safe arena to discuss it. And as for Puri’s father, he did not want to burden his children. There was another reason too, as Dr Anindya Raychaudhuri of the University of St Andrews says: ‘For all the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust, in most cases it was easy to distinguish between bad and good. In partition, it just isn’t.’ Families do not know how to cope with partition when one’s father or uncle may well have killed their neighbor. Therefore in such a set-up, no one discusses it. Most of the partition memories are bound up in shame and honor. It then becomes difficult to disentangle all of that and think of what made people do what they did. In partition, there were perpetrators on all sides, and obviously within families. So, for all these many reasons, there was silence.

Yet silence can be noisy. There were signs: the political unity between different South Asian groups in Britain, already fragile, started to dissipate in the early 1980s. Prejudices persisted about marrying a Hindu or Muslim. When old friends got together they would sit and reminisce about “home”, but this “home” may not be the country their extended family lived in on the Indian subcontinent. Home could be the so-called enemy state. For the subsequent generations in Britain, where identity was complex, they wanted to know and understand. In Britain, these stories matter- for second and third-generation British South Asians it explains their history: who they are and in the context of the Empire, why they are in Britain. One woman got in touch to say her eighty nine year old father, upon hearing the radio programs, shared his awful story for the first time. They had been a catalyst for him to talk about his own painful experiences. She added, “How he kept quiet for seventy years I don’t know.”

This is the same case regarding Puri’s father, Ravi Dutt Puri, who was born in 1935 in Lahore, Punjab, in British Colonial India. He broke his silence after nearly seventy years to speak about what happened to him during the partition of British India- when he was just a twelve-year-old boy. He never returned to the place of his birth, the place he was forced to leave, the place he hoped to see again always.

“In Bengali there are two separate words for home. Bari has the connotation of permanence; it does not matter where you live now, it is your desh, the home of your ancestors, it is where you belong; even if you haven’t seen that place, it is where your ancestry can be traced. Basha is where you lodge at the moment.” (Puri, 263)

Children born into refugee families understand transcience and fragility, that things can change quickly, and the feeling of being rootless and impermanent, that there is o ften no place to go back to that they feel belonged to. Not all, but most families who lived through partition and went on to migrate to Britain were refugees. This double displacement and the consequences were passed down through the generations, both knowing and unknowingly, with education being the one thing that couldn’t be taken away from them. Understanding oneself and one’s place in Britain depends on so many things, mainly the wider political context. Anindya bought a house in Edinburgh with his wife around the time of the referendum to leave the European Union. After the decision by the majority ‘Brexit’, and the reports of an increase in racist incidents, it became more important to him to have the security of his own home.

Urvashi Butalia says, “The exploration of memory and history is not something that is or can ever be finite. One cannot begin to open up memory and reach a point where one can say it is done and dusted. Every historical movement that offers up the possibility of looking at it through the prism of memory demonstrates that the more you search, the more there is that opens up.”

Veena Dhillon discovers poems and essays written by her mother during the 1980s. she found them some twenty five to thirty years after they had been penned. Stories and histories that had lay dormant since 1947. She acknowledges that she feels like she knows her mother better now. the writings, Veena believes, were her mother’s way to ensure their family history would not be forgotten, “because in lots of ways I am rootless”, she says. She thinks that her mother was trying to give her roots. She has never been to the geography of the place where her family and ancestors lived for centuries. She feels that perhaps her mother was trying to give her something because she didn’t have a root. She supposes that it was another piece of the jigsaw. When she was a kid, Dhillon would look into the mirror and wonder if she came from outer space. This is a sign of someone who doesn’t know where she belongs. She says her roots are in Scotland now, but she knows how people look at her- an aging Indian woman. An incongruous thing. Not one thing or another. She is not sure if she feels rootless because she is the child of immigrant parents or because the rootlessness goes back further than that, which is the uprooting from West Bengal in 1947.

Two months before his death, Puri’s father described the murders he witnessed, and in his eighty-second year of his life, he remembered every detail as if he were a twelve-year-old boy watching from the roof of his grandmother’s house. The image of the mothers seeing their children being killed had never left him, even though he hadn’t spoken of it. He did not want to burden the children as there was nothing pleasant to tell is what he would tell. He did not tell even his friends or his wider family. His closest cousin brother, who was with him in Delhi from 1950, was surprised when Puri told him of what her father had witnessed during the Partition. He said he had never once mentioned it. Her father, like those of his generation, was also resilient. He did not forget what it was like to be a refugee, and always felt empathy for those in a similar predicament. In his first letter home from England, he was so shocked by the November cold and grey, he wrote that the sun never rises on the British Empire. He continued on as the worst had already happened to him in 1947 when his family lost everything and was forced to leave their home. In such a scenario, the concept of home and where you belong changes forever. Moga, then Jalandhar, and then Delhi where the family moved to, did not feel like home. So “why not move again?” (259) he asked.

For Ravi Dutt Puri, home could be many things. He did not feel that he had to choose. He lived in Lahore for twelve years, India for fourteen, and England for fifty-eight. He always wanted to return to the city of his childhood but never did. His concept of home was where his children and grandchildren were. But it was also Lahore, the place of his birth. So too was it India, his blood and soul. His generation has and will always be that of a no-man’s land where they belong. Her father saw it as liberating: he could reinvent himself.

Kavita Puri also felt a profound connection to Lahore as she almost had a physical reaction whenever she met anyone from there or read about it. She also felt tied to India, where her father’s family moved to, where she scattered his ashes. Regarding India, she had always felt like an observer but with the act of placing his ashes in the Ganges, she felt her place in the line of her ancestors who had done the same. So, she is definitely anchored to India, But “Britain is my home”, she says. She was born and raised there. The end of the empire saw her father leave Pakistan for India, but it also brought him to Britain where he finally rooted himself to- like when you repot a plant, break the root, but see it grow vigorously. Born as a subject of the British Raj, her father died a British citizen. “We are all, every one of us, post-colonial citizens” (262), she says.

Conclusion

A large number of Partition survivors have lived their lives with silence in a deliberately chosen state. Speaking about the Partition experience is just like scratching the wounds that have not yet healed. Thus, every individual has had a unique experience, yet all these narratives have one thing in common. They prove that hardships cannot shatter them. They, once again, gathered the pieces of life which was so precious to them. They had striven so hard to save it and now they could not let it go at any cost. These narratives are a testimony to the fact that no amount of adversity can dissuade one from his determination to live.

Their lives themselves are the narratives in will-to-live. What was revelatory in these interviews was the connection that people had with the land that was left behind, the land that is considered “enemy territory”; the land that so many people think of as home, even if that concept has been modified, encompassing the country they moved to on the Indian subcontinent as refugees and the place that they eventually migrated to. Bari is where they wish to return to one last time: to see the tree they climbed as a kid, to visit their mother’s grave, to have their ashes scattered.

As Bishvanath Ghosh says in his review of the book, there are books that serve as refrigerators preserving those memories—manuals one can turn to during dark phases— an embodiment of sustaining hope and the will to live.