Across centuries and civilizations, few minds have shaped the course of empires like Sun Tzu and Acharya Chanakya. Though separated by geography and culture—Sun Tzu emerging from ancient China’s military corridors and Chanakya from the political ferment of Mauryan India—both crafted doctrines of strategy that continue to echo on battlefields, boardrooms, and political chambers today. Their ideas were not mere war tactics but full-blown philosophies of power, governance, human behavior, and psychological manipulation. This article explores the intellectual divergence between these two legendary war philosophers, not to compare, but to understand the distinct worlds they imagined, the tools they wielded, and the legacies they left behind.

The King's Role and the Mind Behind the Throne

In Sun Tzu's worldview, a general stood above all else on the battlefield. The king, often a product of dynastic inheritance, was considered fallible and emotionally vulnerable. Sun Tzu emphasized that a competent general must sometimes even defy royal commands to secure military success. To him, the battlefield was not a place for the ego of monarchs; it was a stage where discipline, deception, and control reigned supreme. He instructed his generals to exploit the character flaws of enemy kings, using their emotional instability as a weapon. If a king was arrogant, hot-tempered, or indecisive, Sun Tzu advised using spies and psychological tactics to inflame these weaknesses.

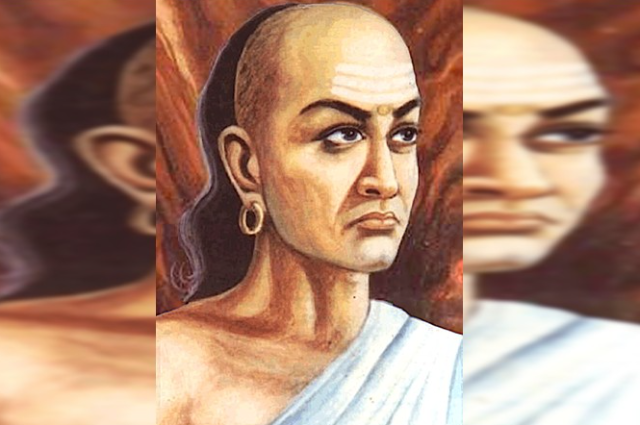

Chanakya, however, inverted this structure entirely. For him, the character of the king was the foundation upon which an entire empire rested. He didn't just advise kings—he molded them. The king, under Chanakya's guidance, was not merely a ruler but a yogi in armor—selfless, emotionally unshakable, morally upright, and intellectually disciplined. His ideal ruler was resistant to lust, greed, and fear, trained to remain composed whether in the flush of victory or the depths of loss. Chanakya believed that a morally fortified king was the best defense against enemy manipulations. In his vision, the mind of the king had to be so prepared that no external destabilization—psychological or political—could break it.

Where Sun Tzu planned around the king’s flaws, Chanakya engineered a king without flaws. This divergence lays bare the difference in cultural frameworks—Sun Tzu saw strategy as a shield against weak leadership. While Chanakya made strong leadership the central pillar of the tactic itself.

Soldier Motivation and Morale: The Heart of the Army

Both Sun Tzu and Chanakya understood that wars are won more by the morale of the soldiers than by the sharpness of their swords. In Sun Tzu’s doctrine, a general must kindle rage in the hearts of his troops. By channeling their anger and guaranteeing an equal share in the spoils of war, soldiers would commit themselves wholly to the fight. His focus was materialistic and emotionally stirring base instincts to trigger brave actions.

Chanakya acknowledged the importance of financial incentives and structured bonuses for acts of valor. However, he reached deeper. He believed that true and lasting soldier motivation stemmed not only from reward but also from spiritual purpose. Chanakya devised mechanisms to link kings with divine authority, using astrologers and priests to frame wars as sacred missions. Soldiers weren't merely fighting for gold or glory; they were defenders of dharma, agents of a cosmic order. Their battle was not just for a kingdom, but for righteousness.

In this, Chanakya tapped into a cultural reservoir that transformed a soldier’s duty into a spiritual commitment. This theological dimension gave his armies a psychological edge—devotion, after all, fuels sacrifice in ways greed cannot.

Espionage: Eyes in the Shadows

Both thinkers were centuries ahead of their time in recognizing the importance of espionage. Sun Tzu classified spies into five types, valuing "converted spies" most—enemy agents turned traitors. His intelligence network aimed to minimize risk to his side while maximizing information extraction from the enemy. Sun Tzu’s espionage was elite, silent, and sharply tactical. It relied heavily on infiltration, surveillance, and manipulation—subtle, methodical, and often executed through local collaborators within the enemy's structure.

Chanakya, by contrast, institutionalized espionage into the fabric of the state. He didn’t wait for spies to emerge; he trained them—actors, ascetics, dancers, merchants, widows, and even children. These spies weren’t just informants; they were social chameleons embedded across every layer of society. Chanakya’s idea of intelligence was not just about gathering data but influencing society itself, turning trust into a weapon. He created roles like the Sadhu-Spy, who gained public reverence through staged miracles, only to later be used for intelligence operations.

While Sun Tzu's spy network resembled a scalpel—precise and controlled—— Chanakya’s was more like a web, vast and intertwined with everyday life. The two approaches illustrate a significant difference in statecraft: Sun Tzu’s covert operations functioned in tandem with military command, whereas Chanakya’s intelligence operated as a parallel pillar of governance.

Warfare Doctrine: The Dance of Steel and Strategy

When it came to warfare itself, Sun Tzu advocated for brevity and brilliance. A long war, he wrote, drains morale and empties treasuries. His goal was to win without fighting, if possible. Deception, ambush, illusion, and psychological manipulation were his weapons of choice. He emphasized terrain analysis, enemy fatigue, and indirect assault. For Sun Tzu, a battlefield was a canvas of confusion, where the one who could create more uncertainty for the other would prevail. He opposed siege warfare due to its high cost and promoted strategies to lure enemies out of strongholds.

Chanakya agreed on the war’s economic burden and also preferred resolution through diplomacy—Saam (conciliation), Daam (bribery), Bhed (division), and only then Dand (punishment). But when war was inevitable, he didn’t merely focus on the battlefield. He wove warfare into the larger scheme of governance. He tailored military units to specific terrains, rejecting Sun Tzu’s reactive approach. For each terrain—mountain, swamp, jungle—he created customized units. This ensured that the state wasn’t limited by the geography of conflict but rather trained to master it.

Where Sun Tzu’s strength was swift tactical warfare, Chanakya’s was strategic endurance. Sun Tzu danced to the rhythms of the present; Chanakya composed symphonies for the future.

Psychological Warfare: The Mind as a Battlefield

In Sun Tzu’s writings, the enemy’s psychology was a treasure trove waiting to be plundered. He believed that wars are fought first in the mind—unsettle the enemy, confuse them, drain their will to fight. He cataloged indicators of weakness: if birds flew over an area, it was empty; if dust rose straight, infantry was marching; if soldiers drank before officers, discipline was lacking. He advocated ambushes when the enemy was fatigued, manipulation when their guard was down, and retreat when advantage slipped. His warfare was a chess game of moods, instincts, and perception.

Chanakya, too, believed in psychological warfare but operated it through a different mechanism. His primary instrument was ideology. He aimed not just to defeat an enemy army but to rewire the enemy society. Through religious symbols, economic infiltration, and social propaganda, he could shake the enemy's confidence from within. His agents didn’t just observe—they acted: seducing, misleading, converting, poisoning. He didn’t want to merely win battles; he desired to dismantle the enemy’s belief in their sovereignty.

Thus, while Sun Tzu crafted illusions to cloud judgment, Chanakya manipulated the truth to change loyalty. Both saw the mind as a primary front in warfare, but one painted illusions while the other rewrote realities.

Economic Warfare and Statecraft

Sun Tzu’s focus rarely extended beyond the war front. He warned that the longer a war dragged on, the weaker the state became. His economic insights mostly emphasized supply chains, resource preservation, and logistic efficiency. He famously argued that capturing enemy provisions was smarter than transporting one’s own. His brilliance lay in calculating costs—not just of war, but of each maneuver within it.

Chanakya, being a full-spectrum economist, saw war as one component of a grander machinery. The Arthashastra is not just a manual of war; it is a constitution for nation-building. Chanakya discussed taxation systems, revenue models, labor laws, trade policy, and agriculture. He built a vision where war was only waged if it served the economic and ethical objectives of the state. To him, soldiers were not just warriors but state employees. Their deployment and treatment reflected the fiscal health and moral compass of the empire.

This difference showcases the fundamental dissimilarity between the two thinkers—Sun Tzu was a military strategist working within the state, while Chanakya was the architect of the state itself.

Diplomacy and Foreign Policy

Sun Tzu’s diplomatic insights centered around intimidation, image projection, and deterrence. To him, a well-prepared army prevented war by making the cost of conflict evident to the enemy. His diplomacy was subtle, often non-verbal, transmitted through strength and silence. He believed that confrontation was a failure of diplomacy.

Chanakya, on the other hand, created a rich diplomatic tapestry. His mandala theory conceptualized the world as concentric circles of allies, neutrals, and enemies, constantly shifting in roles. He categorized neighboring states and prescribed tailored strategies—ally with your enemy’s enemy, betray your ally if state survival demands it, use gifts, marriage, treaties, or even threats. His diplomacy was as fluid as it was ruthless. He understood the psychology of kings, ministers, merchants, and citizens and used it to bend them to his will.

Where Sun Tzu avoided wars through demonstration of might, Chanakya avoided wars by manipulating the very structure of inter-state relationships.

Sun Tzu's Art of War is one of the most translated texts in the world, influencing not only generals but CEOs, politicians, and athletes. Its appeal lies in its brevity, universality, and adaptability. From battlefields to boardrooms, his axioms echo across cultures.

Chanakya’s Arthashastra, rediscovered in the early 20th century, is far more expansive. It doesn’t just guide a war—it constructs a civilization. Its influence on Indian political thought, strategic philosophy, and administrative models is immense but localized due to its complexity and linguistic barriers. Yet, modern strategists and economists alike now revisit it for its layered vision.

Sun Tzu gave us principles for confrontation. Chanakya gave us the blueprint of a state ready to confront or co-opt, to wage war or weave peace. The two minds didn’t merely think differently; they thought from different worlds.