Tracing Historical Roots and Contemporary Realities of Inequality

Gender discrimination, though widely discussed in modern times, remains deeply entrenched in the social fabric of many societies, including India. This inequality, shaped by centuries of historical, social, religious, and economic factors, continues to influence women's roles, rights, and opportunities in subtle yet profound ways. Despite legal reforms and increasing awareness, a large section of Indian women still faces systemic barriers to achieving true equality.

Historical and Economic Roots of Gender Inequality

To understand gender inequality in contemporary India, it is essential to examine its historical and economic foundations. According to a report by the World Economic Forum, women make up half of the world’s population but earn only 10 percent of the global income and own just 1 percent of registered property. This global imbalance is a reflection of centuries of institutional discrimination that prioritized male control over wealth and resources.

The origins of gender-based inequality can be traced back to the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agrarian ones. In early human communities, labor was divided based on physical attributes. Men, generally more muscular due to biological differences, were tasked with procuring food, while women Supervised domestic responsibilities and food preparation. Although this division of labor initially emerged.

Due to pragmatic concerns, it eventually led to a skewed valuation of roles. The ability to procure resources became associated with power and control. Consequently, men began to dominate economic and social systems, which laid the foundation for male superiority and female subordination.

This imbalance was later institutionalized through religion, tradition, and law. Over centuries, different civilizations across the globe crafted social structures that assigned women a subordinate status. In many religious texts and legal codes, women were often considered the property of their fathers or husbands, limiting their rights over their own lives and bodies.

Gender Discrimination Across Institutions

Gender-based discrimination did not remain confined to individual households but seeped into every institutional layer of society. Religion, education, law, and social customs collectively reinforced the belief that women were inherently inferior to men. This led to practices such as child marriage, female infanticide, denial of inheritance, and restrictions on mobility and education. In many communities, rituals, and customs dictated a woman’s behavior, appearance, and role, often to the point of erasing her individuality.

The consequences of this discrimination are still visible today. Even as societies progress technologically and economically, the cultural mindset around gender roles remains resistant to change.

The Women’s Movement in India: A Historical Overview

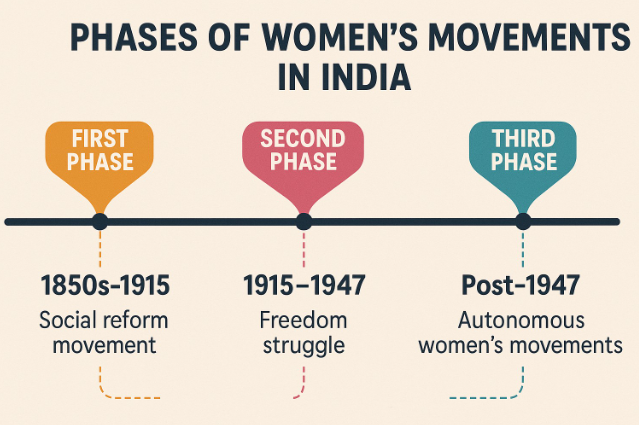

First Phase: Pre-British and British Era

The early stages of the women’s movement in India coincided with the social reform movements during the British colonial period. Although the status of women in India has varied across different historical periods, the colonial era marked a significant phase when numerous social reformers actively championed women's rights. Practices like Sati, child marriage, and denial of education for girls came under scrutiny.

Although the status of women in India has varied across different historical periods, the colonial era marked a significant phase when numerous social reformers actively championed women's rights Roy's efforts resulted in the Sati Regulation Act of 1829, while Vidyasagar worked tirelessly to promote widow remarriage and female education. Despite the progressive nature of these efforts, they were often top-down reforms initiated by men on behalf of women.

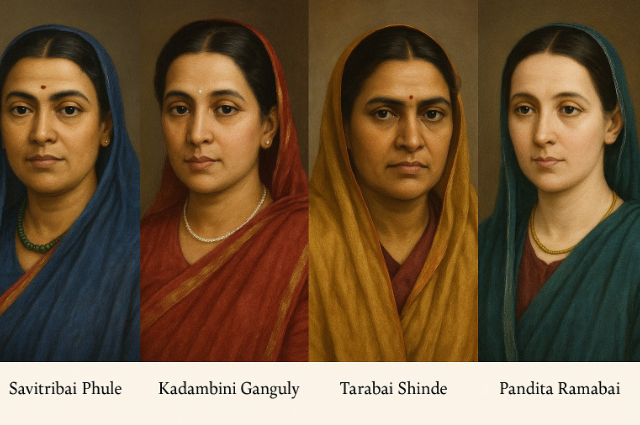

However, women too began to assert themselves during this period. Kadambini Ganguly became one of the first female doctors in India. Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy spoke openly against the devadasi system and worked toward women's health and education. Anandibai Joshi and Kamini Roy also broke societal barriers by pursuing higher education and advocating for women’s emancipation.

Second Phase: Gandhi's Era and the Freedom Movement

The second phase of the Indian women's movement gained momentum during the Indian freedom struggle, particularly under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi recognized that for India to achieve true independence, women—who constituted half the population—had to be active participants in the national movement.

He focused on issues affecting women, such as domestic violence, alcoholism, and social inequality, which encouraged many women to step out of their homes and join the freedom struggle. This era witnessed the formation of women-specific organizations and greater visibility of women in public spaces. The involvement of women like Sarojini Naidu, Aruna Asaf Ali, and Kasturba Gandhi became emblematic of this shift.

Third Phase: Post-Independence to the Present

Following India’s independence in 1947, there was a general belief that legal equality granted by the Constitution would naturally translate into social equality. However, this assumption overlooked the deeply rooted patriarchal attitudes that continued to govern daily life.

During this phase, attention turned to previously overlooked issues such as domestic violence, workplace safety, political representation, and child custody. While the Constitution guaranteed equal rights, the implementation of laws remained inconsistent.

This phase witnessed notable contributions from both men and women, who played pivotal roles in advancing the cause of gender equality through social reform, education, and legal advocacy. Savitribai Phule, who had already opened the first school for girls in 1848, remained a symbol of educational empowerment. Tarabai Shinde authored Stri Purush Tulana, widely regarded as India’s first feminist text. Pandita Ramabai challenged caste norms and advocated for women's autonomy, Rani Lakshmibai and Rani Durgavati are often celebrated as warriors, but even these praises are laced with patriarchal undertones, as seen in the popular expression comparing Lakshmibai’s bravery to that of a man.

Present-Day Challenges and Realities

Despite legal frameworks promoting equality, the lived experiences of many women in India tell a different story. Statistics reveal a grim picture of persistent violence and discrimination.

A significant percentage of married women report experiencing physical, emotional, or sexual violence. According to the National Family Health Survey, about 33 percent of women have faced some form of domestic abuse. Approximately 26 percent have experienced spousal violence, while 6 percent suffered violence during pregnancy. These figures underline a stark reality: home is not always a safe space for women.

Certain state's record higher crime rates against women. Assam leads in overall crimes, while Uttar Pradesh tops the list for murder and rape cases. States like Telangana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu have witnessed rising instances of cybercrime against women.

Social norms continue to propagate gender bias. Practices such as female feticide, dowry harassment, and the notion of daughters as liabilities persist, often perpetuated by both men and women. These behaviors are a result of centuries of conditioning, where even mothers-in-law may perpetuate the same discrimination they once endured.

Misconceptions About Feminism

Feminism in India is often misunderstood. Many equate it with male-bashing or assume it advocates for female superiority. However, at its core, feminism is about equality—not dominance. Its objective is to deconstruct systemic inequalities, fostering a society where individuals of all genders can coexist with mutual respect, equal status, and equitable access to opportunities.

Feminists in India have also had to navigate the challenge of inclusivity. While some movements focus solely on women’s rights, others have tried to incorporate LGBTQ+ concerns. However, fears of diluting the central message sometimes hinder these alliances. True equality can only be achieved when all marginalized identities are included in the conversation.

Legal Frameworks and Implementation Gaps

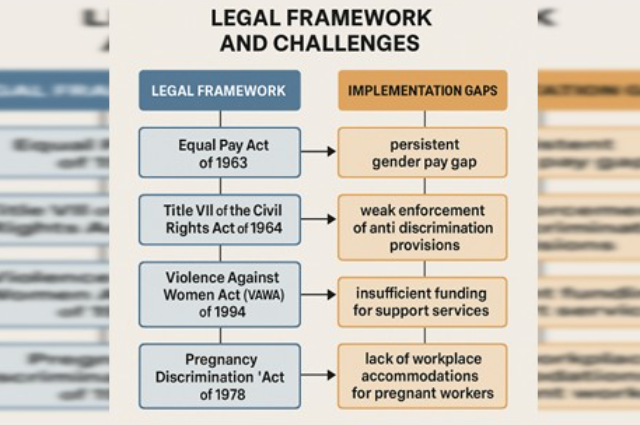

India has enacted several progressive laws aimed at protecting women and ensuring equality. The Equal Remuneration Act of 1976 mandates equal pay for equal work. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, of 2005 provides civil remedies for abuse within the household. The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013 aims to make professional spaces safer for women.

However, the gap between law and implementation remains wide. Conviction rates in rape cases are alarmingly low due to poor investigation and prolonged legal processes. At the same time, some laws like Section 498A (dowry harassment) are occasionally misused, which leads to a perception of imbalance. Nevertheless, these laws are crucial for protecting genuine victims, and the solution lies in better implementation, not dilution.

The issue of marital rape remains unaddressed legally in India. Despite widespread advocacy, the legal system still does not recognize non-consensual sex within marriage as a crime, perpetuating the idea that marriage equates to permanent consent.

Another issue is inheritance. Though the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, of 2005 grants equal property rights to daughters, many women forgo their share due to social pressure or fear of family conflict. Similarly, very few women have complete autonomy in choosing their life partners. Data suggests that only 5 percent of Indian women have full control over decisions related to marriage.

Taboos and Lack of Awareness

Menstruation remains a taboo topic in many parts of India. This leads to misinformation, poor hygiene practices, and health issues among adolescent girls. Religious restrictions, such as the ban on menstruating women entering the Sabarimala Temple, highlight the continued stigmatization of natural biological functions.

Evolution of Rape Laws and Landmark Cases

The Nirbhaya case of 2012 was a turning point in India's approach to gender-based violence. The public outrage led to the formation of the Justice J.S. Verma Committee, which recommended major changes to existing laws. As a result, the definition of rape was expanded beyond just vaginal intercourse, and punishments were made more stringent. The 1973 Aruna Shanbaug case exposed the inadequacy of restrictive legal definitions, which resulted in serious crimes receiving unduly lenient punishments. The Road Ahead

A society cannot progress if half its population is denied basic rights and dignity. Empowering women is not just a moral imperative but also an economic and social necessity. A world founded on true equality would be marked by enhanced peace, justice, and compassion.

To move forward, there must be continued awareness, education, and legal reform. Most importantly, there needs to be a shift in mindset—both among men and women. Patriarchy is not sustained by men alone; it is a system that women too have internalized and reproduced.

Women must be seen as complete individuals, not as daughters, wives, or mothers first, Their identity should not be tied to a man or a household. As long as girls grow up being told they "belong to another home," the fight for equality will remain incomplete.

Gender discrimination in India is a deeply rooted issue that requires sustained efforts to dismantle. Legal reforms, education, social movements, and cultural shifts must work in tandem to achieve real change. The vision of a world where women are treated with respect, equality, and justice is not just desirable—it is essential. The struggle continues, but with awareness and collective action, an equal society is within reach.