Every human has two weapons with him to choose from throughout their life- power and forgiveness. What he chooses depends on the moment when fate calls upon him. When you wield power, you may conquer, you may destroy, but when you embrace forgiveness, you transcend, becoming an embodiment of divinity. Those who seek vengeance with the weapon of power in their hand walk the path of death; those who hold forgiveness carve a path of wisdom.

Throughout history, rulers have often chosen the first weapon power, bending everything in their way to fulfill their desires. Many, in their rise to greatness, forget their roots, losing themselves in the intoxicating grip of dominance. Few remain unchanged, and even fewer, upon realizing their mistakes, have the courage to seek redemption, to be a better man.

Ashoka the Great was not always the title bestowed to Ashoka. Once, he was Ashoka the Terrible, a man so ruthless that even the maids sent to seduce him feared him. A man who painted the rivers of Kalinga red, who slaughtered his own brothers, leaving only one alive on his path to the throne, who crushed anyone who dared stand in his way, even the court ministers.

Though power is a big thing in the kingdoms of ancient India, alone it is hollow. The man who once thrived on conquest eventually realized that strength is meaningless if not balanced with its other half, forgiveness.

The Land of Heaven, Drenched in Blood

The Land of Heaven, that’s what the Japanese once called India. A land rich in wisdom, culture, and prosperity, so divine in its essence that it seemed untouched by the brutality of the world. A place where scholars, travellers from far away nations come to get some type of spiritual essence met. But that image broke when Ashoka brought his war to Kalinga.

Kalinga, a small place compared to Ashoka's dynasty, was a land unlike any other. In an era of monarchs, it stood as a beacon of democracy. Its people lived in peace, governing themselves, content in their independence. But for Ashoka, this was unacceptable, he wanted glory, he wanted more than what his father or grandfather has ever achieved. In his eyes, Kalinga’s defiance was an insult to his empire. He waged war not just to conquer land, but to break the spirit of those who dared to remain free. He wasn't interested in the small land, but he was drunk in the power he held.

Even in the grand stage of history, from the Battle of Panipat to the Indian Revolution, no battle was as bad as Kalinga. Rivers ran red, bodies piled upon bodies, and the cries of the fallen shook the heavens. Over 100,000 lay dead, 150,000 were taken as prisoners, and countless more perished in the aftermath. This was not war, it was annihilation.

Regret Carved in Stone

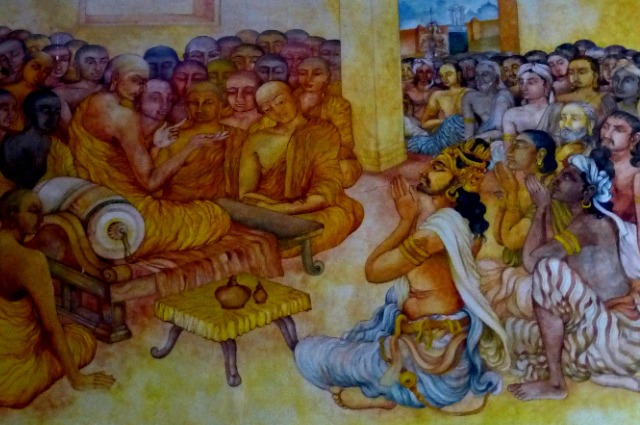

History usually highlights this as Ashoka’s turning point to a man of peace, that seeing the devastation he had caused, he abandoned war and embraced Buddhism. But transformation isn’t instant. A man who once sought pleasure in bloodshed doesn’t become a saint overnight.

Ashoka’s hatred wasn’t a flickering flame, it was molten lava, waiting to erupt. Even after Kalinga, his fury did not fade immediately. It took years of self reflection, regret, and nightmares. This was a man who had ordered executions without hesitation, who rewarded those who slaughtered followers of other religions. And yet, power alone had left him empty.

His regret wasn’t just something he felt, it was something he ensured the world would remember. He did not erase his crimes; he recorded them.

In his 13th Rock Edict, he confessed:

"One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were slain, and many times that number perished. After that, now that Kalinga is annexed, the Beloved of the Gods is devoted to a strong practice of Dharma, to the love of Dharma, and to teaching Dharma."

He did not try to justify his actions. Instead, he admitted that his conquest brought him no joy and that his greatest victory felt like his greatest defeat.

Even after his so-called transformation, he struggled. When one of his men brought him his own brother’s severed head, for the reward of beheading a person of a different religion, Ashoka, who once bathed in blood, felt only sorrow and despair. That was when he truly broke. His only brother whom he loved, and really enjoyed being with was killed because of his own policies. Just because he was blind once again and wasn't tolerant of other religious practices.

From Destruction to Dharma

Ashoka did not just renounce war, he spent the rest of his life trying to undo the harm he had caused. He carved his lessons into stone, ensuring that future generations of kings would not repeat his mistakes. His pillar edicts, spread across the subcontinent, bore his regrets and resolutions.

In his 1st Rock Edict, he declared:

"No living being must be slaughtered or offered in sacrifice."

A man who had once caused the rivers to be full of blood now forbade even animal sacrifices.

In his 7th Pillar Edict, he admitted his past ignorance:

"I did not exert myself for nearly two and a half years, but now I have been closely associating with ascetics, the householders, and those who follow other religions."

He did not merely convert to Buddhism and rule in silence. He actively engaged with different faiths, understanding and respecting them all.

In his 6th Rock Edict, he declared:

"Whatever effort I make, it is for the welfare of all. And that all men should be free from fear and live in peace."

This was not the decree of a tyrant, but of a man who had seen the horrors of his own ambition and chosen to walk a different path.

Can a King Be Great?

Does redemption make a man great? Can a man who killed 99 of his own brothers, who turned rivers into graves, ever truly wash away his sins?

Perhaps the answer isn’t in erasing the past, but in acknowledging it. Ashoka isn’t considered great simply because he changed, but because he admitted his mistakes, recorded them for the world to see, and dedicated his life to being better.

Of course, this doesn’t erase the bloodshed. It doesn’t bring back the countless lives lost under his command. But then again, which king in history is free of such crimes? The difference is that Ashoka chose to leave behind a legacy of wisdom rather than war.

Ashoka isn’t just a king in Indian history, he is a legend. His symbol stands in our national emblem. His pillars remain across the subcontinent. And the faith he once spread has reached every corner of the world.

He may have started as Ashoka the Terrible. But by the time he left this world, he had become something more. Something greater.

A man who was once feared had become a man who was remembered, not for his cruelty, but for his change.

Ashoka may have walked the path of destruction, but in the end, he died on the path of peace.