“Creation often comes along with destruction, who trails just behind looking for a chance to move ahead.” is a quote I read in a book once, though I never understood what it means in my younger years.

How come destruction comes after creation? shouldn't it come before? Or why would creation bring destruction rather than prosperity? The question was answered when I started reading about the chemist Fritz Haber. A man who lost everything while creating the best for his people.

Fritz's most famous achievement, the Haber-Bosch process, allowed for the large-scale production of synthetic fertilizers, feeding billions of people worldwide. Yet, at the same time, the man who created the formula to feed billions also played a leading role in developing poison gas weapons used during World War I, bringing destruction and mayhem on millions.

The question that arises with Fritz Haber's choices and invention is, what is he? A hero or a villain? A savior or a war criminal? His life was a tale of brilliance, patriotism, and tragedy, filled with triumphs that reshaped human civilization and ethical dilemmas that still haunt us today.

Early Life and Education: A Brilliant Mind in the Making

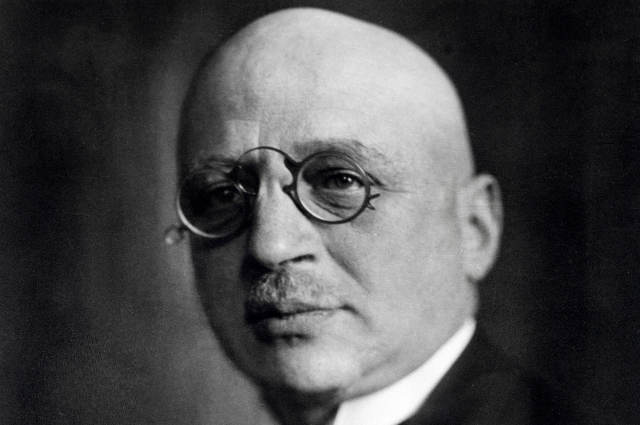

Fritz Haber was born on December 9, 1868, in Breslau, Prussia (now Wrocław, Poland) into a wealthy Jewish family. His father, a successful merchant, wanted him to enter the family business, but young Fritz was just not interested, preferring science over some family work.

As he grew older, he joined college to study chemistry at the University of Heidelberg under the famous scientist Robert Bunsen (inventor of the Bunsen burner). Later, he transferred to Berlin and Zurich, where he studied under some of the finest chemists of the time.

By 1894, he had earned his doctorate in chemistry and began his career in industrial research. He quickly became known for his practical approach to chemistry, working on ways to make industrial processes more efficient.

One of the greatest challenges of the time was the "Nitrogen Crisis", the need to produce enough fertilizer to feed a growing population. With declining ammonia in the world, it had become a dilemma, with hundreds of scientists trying to find an answer. Haber would soon solve it.

The Nitrogen Crisis: Why the World Needed Ammonia

Ammonia gas is a naturally formed liquid/gas which is particularly needed by plants and crops to grow, which results in food. By the early 20th century, the concentration of ammonia in nature was far less compared to the demand.

The only way for farmers to use it in agriculture was to rely on natural fertilizers such as:

- Guano (bird droppings) from South America

- Saltpeter (sodium nitrate) from Chile

However, these resources were limited and expensive. Scientists knew that the atmosphere contained 78% nitrogen, but plants couldn't absorb it in its gaseous form. They needed nitrogen compounds like ammonia (NH₃) to grow.

Solving this problem was one of the biggest scientific challenges of the time. Without nitrogen fertilizers, global food production could not keep up with population growth.

This is where Fritz Haber made history.

The Haber-Bosch Process: Feeding the World

In 1909, Fritz Haber discovered a way to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia using:

- High pressure (200 atmospheres)

- High temperature (500°C)

- An iron catalyst

The reaction: N_2 + 3H_2 → 2NH_3

This was revolutionary, Haber had cracked the nitrogen code.

However, this method required industrial-scale production. In 1910, German chemical company BASF and engineer Carl Bosch worked to scale it up, leading to the first industrial ammonia plant in 1913. This marked the birth of synthetic fertilizers, allowing the Green Revolution decades later.

Impact on Agriculture

Synthetic fertilizers now produce over 500 million tons of crops annually. The world population grew from 1.6 billion (1900) to over 8 billion today, largely due to Haber’s process.

Today, nearly half of the nitrogen in our bodies comes from synthetic fertilizers. For this, Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918.

However, his legacy wasn’t just about saving lives, it was also about taking them.

The Dark Side: Haber and Chemical Warfare

Despite his humanitarian contributions, Fritz Haber also became the father of chemical warfare.

During World War I (1914-1918), Germany faced a shortage of explosives, which required nitrates. Thanks to Haber's ammonia process, Germany could mass-produce explosives, prolonging the war.

However, Haber's involvement went further; he personally led efforts to develop poison gas weapons.

The First Chemical Attack in History

In April 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, Haber supervised the first large-scale poison gas attack. German forces released 168 tons of chlorine gas toward French and Canadian soldiers.

The gas caused suffocation, burning lungs, and agonizing deaths. Over 1,000 soldiers died instantly, and thousands more suffered long-term effects.

Reactions:

Many scientists, including Albert Einstein, condemned Haber for violating the ethics of war.

Haber defended himself, claiming that using poison gas was no worse than bullets or bombs.

Tragically, his wife, Clara Immerwahr, a fellow chemist, was deeply opposed to his role in chemical warfare. In despair, she shot herself the day after the first gas attack.

Haber’s Fall from Grace

After World War I, Germany lost the war, and the Treaty of Versailles banned chemical weapons. Haber was briefly wanted for war crimes, forcing him to flee to Switzerland.

Still, he continued his work, even attempting to extract gold from seawater to help pay Germany’s war debts, but the project failed.

Betrayal by the Nazis

Ironically, despite being a German war hero, Haber, who was Jewish, was forced to flee Nazi Germany in 1933. The same government that once praised him now saw him as a traitor.

Heartbroken and exiled, Haber died in 1934, suffering from heart disease.

Haber’s Legacy: A Double-Edged Sword

Fritz Haber’s contributions are both a blessing and a curse.

Positive Impact:

- His invention of synthetic fertilizer feeds half the world today.

- His work allowed modern agriculture to thrive.

Negative Impact:

- His chemical weapons research led to devastating deaths in multiple wars.

- His work indirectly led to Zyklon B, the gas used in Nazi concentration camps—an irony considering his Jewish heritage.

The Ethics of Science: What Can We Learn?

Haber’s story raises deep ethical questions:

- Can science be separated from morality?

- Should scientists be responsible for how their inventions are used?

- Is it possible to be both a hero and a villain?

Haber believed that science should serve both peace and war. Yet, history proves that his greatest achievements also led to some of humanity's greatest tragedies.

Fritz Haber...

Fritz Haber was a brilliant yet controversial figure. His discovery of synthetic fertilizers has saved billions of lives, but his involvement in chemical warfare brought death and destruction.

Even today, his legacy continues; every meal we eat, every crop we grow, and every war we fight owes something to Haber’s discoveries.

Was he a hero or a villain? That depends on which part of his story we choose to remember.