A census is a tool that helps the authority in power to gather information about the people in their country. This collection allows the government to get a detailed snapshot of the nation which in turn helps in decision-making and the development of policy. Imagine collecting such data for a country as densely populated as India that too in a time when the luxury of technology was not available. The first census of our country was not even conducted by our people, nor was it conducted with the aim of welfare of people; rather it was a strategic tool to strengthen the already existent social divisions and to establish absolute control over the nation.

A census is like a mirror which reflects the realities of the society, but this mirror was handed over to people who chose to reflect a distorted image, reinforcing hierarchies and divisions of the society. The 1901 census was not just a record of the Indian population; it was a means to define their identity.

Before the census, India had no official records of its demographics; the nation has always been a land with a labyrinth of identities woven with religion, caste and language. There were several regional variations in social norms and hierarchies. The language identities were fluid. Syncretism allowed various overlapping in cultures and practices that drew from multiple religions which meant that the religious identities were not rigidly defined. However with the coming of the census, these boundaries started to become more evident than ever.

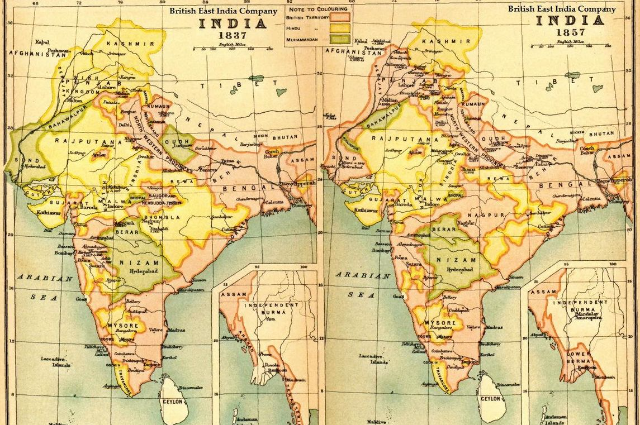

The earliest attempt at counting the Indian population began in the year 1872 under Lord Mayo. The census was not synchronised, different regions were counted at different times. Indians had a deep suspicion regarding the census; they felt that this was an attempt by the British to increase taxes or a ploy to take over their land and property. Lack of proper documentation was also a major challenge because most Indians did not maintain birth or marriage records, so most of the information was based on oral accounts, which could very easily be manipulated. In many households, the information of the female members of the family was not disclosed because they didn’t want to open up to a male surveyor. Local officials, landlords and village headmen were often the ones the British looked up to for data, which created inconsistencies in the data. The report of the 1872 census was from perfect, but it did give a rough estimation of the population, which was revealed to be approximately 206 million.

The next census was conducted in 1901, and unlike the previous one, this was well planned in order to ensure maximum accuracy. Sir Hobert Risley was given charge of the project; under his leadership there was efficiency in data collection this time. The census was designed to collect information on religion, caste, gender, occupation and literacy of the people of India. Since this was a massive project which required a lot of manpower, thousands of people were recruited and trained meticulously to carry out the process efficiently and smoothly.

One of the biggest challenges that the British officials faced in their journey was that the general public was deeply suspicious of the census. To tackle this, they launched awareness campaigns involving various influential figures to assure the people that this was merely a statistical exercise. Enumerators were trained well to handle issues like non-cooperation of the people, to avoid any bias and how to record answers accurately. Apart from this, trial surveys allowed the development of strategies to tackle public resistance and increase efficiency and accuracy.

1901 census was a landmark event which provided an extensive snapshot of colonial India. The census revealed declining population, low literacy rates and the effect of oppressive revenue policies on the people.

The census fundamentally altered the identity of the people and how the people were recognised, leaving behind consequences which affect us till today.

Let’s start by discussing caste. Caste distinctions have always existed in the subcontinent, but they were not always rigid. Mobility and flexibility was possible – this was possible through shifting occupations and intermarriage. Also, the rules of caste were not the same everywhere; there was a scope for regional variations. However, in the process of data collection for the census, the caste was officially recorded and not just recorded, they were labelled as “higher” and “lower”. Apart from this, they also termed some communities as “tribal” and “backward”, depicting them as backward and justifying control over their areas.

So, castes which had some scope of mobility now became fixed in government records. This bureaucratic fixation of caste created more rigid and formalised boundaries, this rigidity also took away the possibility of upward mobility. The census laid the foundation of affirmative action in modern India. The British recognised historical injustice and inequality by classifying some castes into “depressed” suggesting that effort should be put in empowering them. In fact, BR Ambedkar used these colonial surveys to argue for the reservation of these communities, which were later termed as “schedule caste” and “scheduled tribe”, and today, we follow this system of reservation.

Talking about language, language has also been a fluid concept in India with many people being multilingual, and there wasn’t this idea of a mother tongue that we see today. The British also categorised languages into larger families, namely - Indo Aryan which included languages like Punjabi, Bengali and Marathi; Dravidian which had Kannada, Malayalam, Telugu and Tamil, Austroasiatic like Santhali, Mundari and Tibeto- Burman like Assamese, Manipuri. Many regional directors were merged into this classification, stripping them of their identity. The 1901 census deepened the linguistic divide of India, imposing the single “ mother tongue” identity which sow the seeds of linguistic nationalism, which later turned into the demand of linguistic states post-independence. The Andhra movement and the subsequent act of state reorganisation show how rigid and strong linguistic identities became post-independence. The census turned a cultural identity into a tool for politics and till today, language remains a strong political force in India.

The most painful impact of the partition was on religion. In India, many people followed syncretic traditions; the nature of religion was fluid and intertwined with people from different religions often sharing local customs, traditions and festivals. The 1901 census classified people into different religions like Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhist etc., completely ignoring the syncretic nature of religion in India. The British also classified religions as “majority” and “minority” ones, giving rise to an issue which was not that apparent up till now. The census also created a “numerical competition” for e.g. in a census conducted much later in 1931, a rise in the Muslim population was revealed which created a fear amongst Hindus that they would be outnumbered. The rigid, formalised boundaries caused a divide amongst the people, leading to separate electorates later and ultimately culminating into a bloody partition in 1947 and a strong sense of divide and hatred which still persists.

The census was definitely not just a tool for data collection but it was a carefully devised strategy of the British to deepen the divide amongst the people of a diverse unified country and to establish absolute control over the subcontinent. As India still grapples with this divide related to caste, language and religion, the 1901 census serves as a reminder that seemingly neutral policies can sow seeds of hate and shape the fate of a nation.