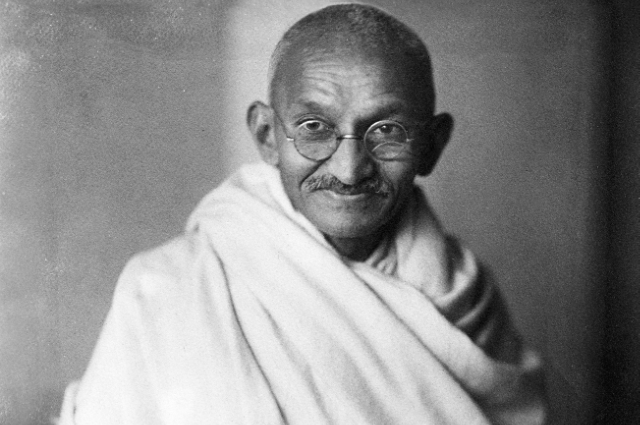

Gandhi’s Legacy in a Digital Civilisation

Mahatma Gandhi, the moral heartbeat of India’s freedom struggle, lived in a world lit by lanterns and guided by handwritten letters. Yet, his voice echoes powerfully in our digital age of algorithms, artificial intelligence, and endless scrolling. Gandhi did not know the internet, but he understood human nature — its capacity for both creation and destruction, compassion and cruelty. His teachings, born in an age of simplicity, now shine as guiding lights through the complexities of modern technology.

The digital era has transformed how humans think, connect, and act. With a single click, we can communicate across continents, influence millions, or spread falsehood faster than truth ever could. We have gained information but often lost reflection; we are connected, yet more isolated than ever. In this paradoxical world, Gandhi’s philosophy offers not nostalgia but direction — a moral compass for the storm of innovation.

Gandhi’s ethical triad — Truth (Satya), Non-Violence (Ahimsa), and Self-Discipline (Brahmacharya) — speaks directly to our times. His belief that moral strength must guide material progress is perhaps more urgent today than in his own century. As we navigate the boundless space of the internet, Gandhi’s ideals remind us that technology should serve humanity, not enslave it; that progress without conscience is peril, and that peace, both inner and outer, begins with self-control.

Thus, Gandhi’s message is not a relic of the past but a living force for the digital present — a reminder that even in an age of artificial intelligence, moral intelligence must lead the way.

Part I: The Philosophical Foundations of Gandhiji’s Thought

1. The Relevance of Gandhian Philosophy in Modern Society

Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy is not a collection of abstract ideals but a lived reality shaped by his own spiritual and moral journey. His declaration — “My life is my message” — captures the heart of his thought: that truth, ethics, and action are inseparable. Gandhi’s worldview was not confined to politics or religion; it was a complete philosophy of life, aiming to harmonise body, mind, and spirit in the service of humanity.

In a time when material progress is often mistaken for real advancement, Gandhi reminds us that true civilisation is measured not by what we invent, but by what we become. His principles of truth (Satya), non-violence (Ahimsa), self-restraint (Brahmacharya), and service (Seva) are not ancient relics but living tools for building an ethical society. Gandhi’s simplicity was not poverty but freedom — freedom from excess, greed, and ego.

Today’s world, characterised by speed and competition, desperately needs Gandhi’s calm moral voice. His call for Sarvodaya — the welfare of all — invites modern societies to rethink progress not in terms of economic growth alone but in terms of compassion, justice, and sustainability. Gandhi envisioned a civilisation guided by conscience rather than consumption, one that respects both human dignity and the natural environment.

Thus, in our age of global connectivity and moral confusion, Gandhi’s message remains a quiet yet powerful force: that no technology, however advanced, can substitute for truth, empathy, and inner peace.

2. The Moral Crisis of the Digital Era

The 21st century has ushered in a revolution of information and communication beyond Gandhi’s imagination. The smartphone has replaced the spinning wheel as the new symbol of human empowerment. Yet beneath this technological triumph lies a silent moral crisis.

Social media has made every voice louder but not necessarily wiser. The speed of digital sharing often outpaces the speed of moral thought. As a result, fake news, online hate, cyberbullying, and digital addiction have become symptoms of a deeper spiritual emptiness.

Gandhi warned that when material power grows faster than moral power, civilisation begins to decay. His insight rings painfully true today. Technology, if guided by greed or ego, becomes an instrument of division rather than connection. The digital world mirrors our inner selves — and what we post, share, or comment reveals more about our character than we realise.

In such a world, Gandhi’s teachings are not merely ethical suggestions; they are necessities for survival. Truth becomes the antidote to misinformation, non-violence the cure for online hostility, and self-discipline the answer to the restless pursuit of likes and validation.

The digital age demands not just innovation, but introspection — a return to Gandhi’s vision of mindful living. His legacy urges us to pause, reflect, and reclaim our humanity before our technology outgrows our moral capacity. Gandhi’s message is a gentle reminder: progress without compassion is no progress at all.

Part II: Satya (Truth) — The Foundation of Digital Integrity

2.1 Understanding Satya: Gandhi’s Pursuit of Truth

For Mahatma Gandhi, Satya — or Truth — was not merely the absence of falsehood. It was the very essence of existence, the divine principle connecting the human soul to God. Gandhi once declared, “Truth is God” (Gandhi, 1927), signifying that the pursuit of truth was not just an ethical duty but a spiritual calling. His understanding of truth extended beyond words; it demanded integrity in thought, speech, and action.

Gandhi’s approach to truth was deeply experiential. He believed that truth unfolds gradually, as one purifies one’s mind and motives through self-discipline and humility. In his Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, he described life as a continuous laboratory of moral and spiritual testing. Each choice, each word, and each action became a reflection of his inner truth.

In today’s digital civilisation, Gandhi’s Satya acquires renewed significance. The modern world is drowning in a sea of half-truths, curated images, and algorithmic illusions. What is “real” is increasingly mediated through screens, filters, and coded biases. Gandhi’s emphasis on living truthfully challenges us to look beyond appearances and seek authenticity in a world of virtual masks.

As Parel (2006) observes, Gandhi’s concept of truth was “an ethical realism” — a belief that truth is both moral and practical, requiring courage to confront comfort and honesty to resist convenience. In an age where truth is fragmented by digital distortion, Gandhi’s Satya becomes the foundation of digital integrity.

2.2 The Digital Age of Misinformation

The internet, while democratizing information, has also weaponised it. The rise of social media platforms has created what philosophers call the post-truth era — a time when emotional appeal often outweighs factual accuracy. Information travels at the speed of light, while verification lags. Deepfakes blur the line between reality and fabrication; propaganda masquerades as news; and algorithms feed users with content that confirms their biases rather than challenging their minds (Pariser, 2011).

Gandhi’s world faced colonial censorship; ours faces algorithmic manipulation. Yet the moral struggle remains the same — the defence of truth against forces of distortion. Gandhi’s Satyagraha, meaning “the force of truth,” was his weapon against oppression. Today, digital Satyagraha must become the moral resistance against misinformation and moral apathy.

Just as Gandhi trained his followers to resist lies with non-violent courage, digital citizens must cultivate awareness, patience, and integrity before reacting or sharing online content. Truth, in Gandhi’s sense, demands moral effort — not passive consumption but conscious participation in building a truthful public space.

2.3 Practising Digital Satyagraha

To practice Satya in the digital world is to make truth a living principle in one’s online behaviour. Gandhi believed that moral reform begins with the individual — the smallest act of honesty can ripple outward to transform society. Translating this into the digital context means:

- Checking facts before sharing or reposting information.

- Rejecting clickbait and emotionally manipulative content that feeds outrage instead of understanding.

- Promoting honest, balanced dialogue, even when it challenges one’s own opinions.

- Using digital media as a tool for enlightenment, not deception, echoing Gandhi’s view that communication must uplift, not exploit.

As Shalini Acharya (2018) argues in her study “Revisiting Gandhi in the Information Age”, Gandhi’s belief in the transformative power of truth should serve as the ethical foundation of our virtual conduct. She emphasises that in a world overwhelmed by data, moral clarity — not more technology — is what sustains real progress.

Practising digital Satyagraha means using technology not for manipulation but for education, not for self-promotion but for self-purification. Gandhi would remind today’s digital citizens that truth is not a trending hashtag but a daily discipline — a quiet act of resistance against the noise of falsehood.

Part III: Ahimsa (Non-Violence) — Restoring Peace in Digital Communication

3.1 Violence in the Virtual World

In Gandhi’s moral universe, Ahimsa — non-violence — was not merely the absence of physical harm but the conscious refusal to injure through word, thought, or intention. For him, violence was not limited to the battlefield; it could live in the human heart, in prejudice, and even in silence. Today, in the vast landscape of the digital world, violence has found new and subtle forms — cyberbullying, hate speech, trolling, cancel culture, and character assassination. The internet, originally built to connect humanity, now often serves as a weapon that divides it.

The anonymity and immediacy of online communication have made it easier to inflict emotional wounds without accountability. A single hateful comment can destroy confidence; a rumour can ruin reputations within hours. Gandhi warned that “anger and intolerance are the enemies of correct understanding” (Gandhi, 1928). His words capture the very crisis of our digital time, where emotional impulsiveness often replaces thoughtful discourse.

For Gandhi, true courage was not in retaliation but in restraint. He believed that responding to hatred with calmness and cruelty with compassion was the highest form of strength. In this sense, Ahimsa is not passive submission but active resistance — a moral power that transforms hostility into understanding. The digital world urgently needs this Gandhian courage, for violence online is not only external; it corrodes the collective spirit of humanity itself.

As Nanda (2020) observes, “In the digital age, the battlefield is no longer physical; it is emotional and ideological. Gandhi’s Ahimsa provides the only sustainable strategy for peace in such a world.”

3.2 Digital Ahimsa: Kindness as Resistance

To live Ahimsa in the digital age means to extend compassion through our keyboards, screens, and clicks. Gandhi believed that every individual carries a moral responsibility for the tone of their surroundings. In virtual spaces, that responsibility becomes even more vital. Each post, comment, or message contributes either to harmony or hostility.

Practising Digital Ahimsa involves daily acts of mindfulness and moral awareness:

- Avoiding offensive language and ridicule, even when provoked.

- Standing up against online bullying, without spreading further hate.

- Encouraging positive, respectful dialogue that builds bridges, not barriers.

- Choosing silence over spite, remembering that peace often begins with patience.

Digital Ahimsa does not mean withdrawal from social media but transformation of how we use it. It asks us to replace reaction with reflection, mockery with understanding, and outrage with empathy. As Pooja Saraswat (2025) insightfully argues, “Gandhi’s Ahimsa must evolve into digital kindness — a new form of moral discipline for a hyper-connected society.” She explains that true non-violence today lies not only in refusing to harm but in actively creating environments where others feel safe, heard, and respected.

Non-violence, then, becomes an act of creation — building digital communities rooted in trust rather than fear. When Gandhi said, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world,” he was speaking across time to every digital citizen. Each click, each share, and each word can either spread division or become an instrument of peace.

To practice Ahimsa online is to reclaim the soul of the internet — to turn technology back into a servant of humanity rather than a mirror of its anger. It is, in Gandhi’s spirit, the quiet revolution of kindness.

Part IV: Brahmacharya (Self-Discipline) — Freedom Through Control

4.1 The Digital Temptation

In Gandhi’s ethical vision, Brahmacharya — or self-discipline — was not limited to celibacy or asceticism. It was a principle of mastery over desire, a conscious effort to bring one’s senses, mind, and will into harmony. For Gandhi, true freedom was not the ability to do whatever one wished, but the power to resist what enslaves the soul. He often reminded his followers that “restraint is the highest form of strength” (Gandhi, 1930).

In today’s world, this idea faces its greatest test. The digital revolution has placed temptation in the palm of every hand. Notifications, social media feeds, advertisements, and endless streams of entertainment constantly compete for our attention. What Gandhi once described as enslavement to material pleasure has now evolved into enslavement to the screen.

Every scroll, every click, and every like is designed to stimulate instant gratification, slowly eroding our patience, focus, and emotional balance. As Tristan Harris (2016) notes in his research on digital addiction, modern technology is deliberately engineered to hijack human attention — turning users into passive consumers rather than active thinkers. Gandhi, who emphasised mindfulness and inner stillness, would have seen this as a profound moral crisis.

To lose self-control in the digital age is not just to waste time; it is to surrender one’s moral autonomy. Gandhi’s Brahmacharya thus becomes a revolutionary concept for the modern mind — urging us to reclaim mastery over the very tools that claim to empower us.

4.2 Practising Digital Self-Discipline

Practising Brahmacharya in the digital context is not about rejecting technology, but about redefining our relationship with it. Gandhi used tools of his time — the spinning wheel, letters, newspapers — but he used them mindfully, as instruments of service, never of distraction. In the same spirit, Digital Brahmacharya calls for a lifestyle of conscious engagement, where technology serves our higher purpose rather than controls it.

To embody this principle in daily life means:

- Limiting screen time to preserve attention for meaningful work and real human interaction.

- Using technology purposefully, as a tool for learning, creativity, and service — not as an escape from silence.

- Avoiding digital overconsumption, recognising that excess information does not equal wisdom.

- Balancing online and offline life, nurturing real relationships, nature, and solitude — the spaces where moral clarity is born.

As Shalini Acharya (2024) observes in her essay “Restraint in the Age of Stimulation: Gandhi and the Digital Mind,” Gandhi’s principle of self-restraint is not outdated but urgently modern. She argues that Brahmacharya offers a pathway to mental peace and sustainable attention in an era of constant overstimulation. Acharya reminds us that Gandhi’s call for simplicity was not anti-modern; it was profoundly human — an invitation to live deliberately, not reactively.

In this sense, Digital Brahmacharya becomes an act of liberation. It frees us from the tyranny of distraction and returns us to ourselves. By mastering the machine, we rediscover our inner stillness — that sacred space Gandhi called the “quiet voice of conscience.” The practice of restraint, far from limiting life, restores its depth and dignity.

The ultimate message of Gandhi’s Brahmacharya for our digital civilisation is this: freedom without self-control is an illusion. True progress is not measured by the power of our devices, but by the peace of our minds.

Part V: Sarvodaya (Welfare of All) — Building a Compassionate Digital Society

5.1 The Meaning of Sarvodaya

The word Sarvodaya — meaning “the welfare of all” — represents the very heart of Gandhi’s social philosophy. It is the vision of a world where justice, equality, and compassion govern human relationships. For Gandhi, no society could be truly free or peaceful until every individual, especially the weakest, enjoyed dignity and opportunity. He often said, “A civilisation is to be judged by its treatment of its weakest members.”

In the 21st century, Sarvodaya takes on a new dimension within the digital sphere. The internet has become the world’s new public square — a place where voices can be heard and knowledge shared. Yet, it has also created new inequalities. Millions remain disconnected, voiceless, or victims of data exploitation. Thus, Gandhi’s dream of universal upliftment demands translation into a digital ethic of inclusion — a world where technology becomes an instrument of empowerment, not exclusion.

The essence of Digital Sarvodaya is to ensure that the benefits of technological progress reach every corner of society, from rural classrooms to marginalised communities. It calls for a digital order founded on compassion, equality, and human dignity — the same moral foundation Gandhi envisioned for his ideal village.

5.2 Digital Inclusion and Ethical Innovation

If Gandhi were alive today, his spinning wheel — the charkha — might well be a symbol of ethical technology. Just as the charkha represented self-reliance and social justice during colonial times, Digital Sarvodaya represents a movement for technological justice in our own. It challenges us to rethink how innovation can serve the collective good rather than corporate greed.

Practising Digital Sarvodaya involves:

- Bridging the digital divide between rich and poor, urban and rural, connected and disconnected. Access to the internet and digital literacy should be treated as a basic human right.

- Promoting technology education for all, ensuring that students, workers, and citizens can use digital tools for learning, creativity, and empowerment.

- Encouraging ethical AI and fair algorithms, so that technology reflects human values rather than amplifies bias or exploitation.

As Nandini Srivastava (2025) explains in her work “Gandhi in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” Gandhian ideals can guide modern policymakers, educators, and innovators toward a more humane digital order. She argues that technology should be designed not for profit alone, but for service — echoing Gandhi’s timeless principle of “Sarvodaya through Sevā” (welfare through service).

Srivastava reminds us that the true test of progress is not in the sophistication of our machines but in the compassion of their purpose. A Gandhian approach to technology would seek not dominance but balance — between speed and sensitivity, innovation and inclusion, intelligence and empathy.

In this vision, Digital Sarvodaya becomes the moral compass of the information age. It reclaims technology as a force for human upliftment, ensuring that the poorest, the voiceless, and the digitally excluded are not left behind.

The digital revolution, if guided by Gandhi’s spirit, could become a new Satya Yuga — an era of truth, service, and shared humanity. For Gandhi, progress was never measured by what we possess, but by how we use it for the good of all.

Part VI: Swadeshi (Self-Reliance) — Local Wisdom in a Global Network

6.1 Redefining Swadeshi for the 21st Century

When Mahatma Gandhi spoke of Swadeshi, he envisioned it not as isolationism, but as a philosophy of moral and economic self-reliance — the idea that a community must sustain itself through its own wisdom, labour, and creativity. In his own words, “Swadeshi is that spirit in us which restricts us to the use and service of our immediate surroundings to the exclusion of the more remote.”

In the 21st century, globalisation and the digital revolution have woven the world into a vast network of interdependence. Yet, the spirit of Swadeshi remains as relevant as ever — not as rejection of the global, but as a reclamation of the local within the global framework. Today’s Swadeshi must be digital Swadeshi — the use of technology to empower local communities, protect cultural identity, and promote sustainable innovation.

Gandhi’s emphasis on self-reliance can guide nations and individuals toward digital sovereignty — the ability to produce, control, and secure one’s own data, software, and creative outputs. It urges us to reduce dependency on exploitative digital monopolies and nurture homegrown innovation rooted in ethics and empathy.

In this light, Swadeshi becomes an act of moral courage — a way to preserve one’s cultural and intellectual independence amidst the homogenising power of global technology. It asks: how can we make the digital world reflect our local values rather than lose ourselves in the virtual crowd?

6.2 Creating Technology with a Conscience

A truly Gandhian approach to technology is not anti-modern; it is morally modern. Gandhi believed that every tool, however powerful, must serve a higher human purpose. His spinning wheel (charkha) symbolised not resistance to progress, but resistance to exploitation — a vision equally applicable to our age of algorithms and artificial intelligence.

To apply Swadeshi in the digital era means developing and using technology with a conscience — guided by truth, restraint, and compassion. It means demanding transparency, fairness, and accountability from the systems that shape our lives.

Practising Digital Swadeshi involves:

- Transparency in data use, ensuring that citizens understand how their personal information is collected and used.

- Respect for privacy and human dignity, rejecting surveillance capitalism and digital manipulation.

- Responsibility in artificial intelligence, where machines enhance rather than replace human moral judgment.

- Promotion of sustainable innovation, ensuring that technological growth does not come at the cost of environmental or social well-being.

As Pooja Saraswat (2025) explains in “Ethics and Self-Reliance in Digital India,” the Gandhian vision of Swadeshi offers a blueprint for ethical digital development — one that prioritises the human spirit over commercial profit. She argues that the true power of innovation lies not in technological dominance, but in technological integrity — the ability to design systems that honour both people and planet.

In an era where global tech giants dominate digital spaces, Gandhi’s message of Swadeshi reminds us that real strength lies not in dependence, but in dignified self-reliance. To be truly modern, the digital world must also be truly moral — and that morality begins with reclaiming our power to create, think, and innovate locally, with purpose and compassion.

Part VII: Technology as a Mirror of the Mind

7.1 The Double-Edged Nature of Technology

Gandhi would have viewed technology as morally neutral — neither good nor bad in itself. Its value depends on the user’s intention. The internet, social media, and AI reflect the human mind: they can either connect or corrupt, enlighten or exploit. The same tool that spreads education can also fuel misinformation and division.

As Nandini Srivastava (2025) notes, “The digital crisis is not technological but moral.” Gandhi’s philosophy reminds us that progress without conscience is self-destructive. The purity of our tools depends on the purity of our hearts.

7.2 Using Digital Platforms for Good

Despite its dangers, technology can also serve truth and compassion. Digital archives, online forums, and virtual exhibitions now preserve Gandhi’s teachings for a global audience. When guided by ethics, social media can become a space for peace — a form of digital Satyagraha.

As Pooja Saraswat (2025) writes, “Digital kindness is modern Ahimsa.” By using technology consciously, we turn it into a mirror of humanity’s better self — a bridge between innovation and moral integrity.

Part VIII: Education and Youth — Reviving Gandhian Ethics

8.1 Teaching Gandhi in the Digital Classroom

Young people today live in a world shaped by screens, social media, and instant information. Gandhi’s principles — truthfulness, empathy, restraint, and service — should guide digital education. Schools and universities must integrate these values into curricula to nurture not only skilled minds but also ethical hearts.

8.2 The Role of Youth as Digital Satyagrahis

Gandhi believed that the youth were the moral strength of a nation. Today, they can be the architects of a new digital ethics — becoming Digital Satyagrahis who use online platforms to spread truth, counter hatred, and promote respect. By embodying Gandhian values, young people can turn the internet into a space of constructive dialogue and collective conscience.

As Gandhi once said, “The future depends on what you do today.” In the digital age, that future rests in the hands of ethical, engaged youth.

Gandhi’s Moral Compass for a Digital Future

Mahatma Gandhi’s life was a testament to the power of moral clarity in a turbulent world. His teachings — Satya (Truth), Ahimsa (Non‑Violence), Brahmacharya (Self‑Discipline), Sarvodaya (Welfare of All), and Swadeshi (Self‑Reliance) — were born in an age of simplicity but speak powerfully to the complexities of our own. In the age of algorithms, where technology shapes thought and action at unprecedented speed, Gandhi’s philosophy is not a relic of the past but an urgent call to conscience.

The digital age offers extraordinary promise — the power to connect, educate, and transform lives. Yet it also presents grave challenges: misinformation, cyber hostility, loss of privacy, and the erosion of empathy. These are not just technical problems but moral ones. Gandhi’s vision reminds us that technology, however advanced, remains a tool whose value depends on the purpose of its use. Without ethical grounding, innovation becomes noise rather than progress.

For Gandhi, change began with the self. Today, that means cultivating digital Satyagraha — the discipline to seek truth, practice kindness, and use technology responsibly. It means embracing digital self‑restraint, fostering inclusive access, and building systems that respect human dignity. Above all, it means empowering the next generation to lead with conscience, turning the internet from a battlefield of distraction and division into a platform for dialogue, compassion, and collective upliftment.

In this way, Gandhi’s moral compass offers a roadmap for the digital civilisation: not a rejection of progress, but a reminder that true progress must be measured not by how fast we innovate, but by how wisely we choose to live. His challenge remains as relevant as ever: “Be the change that you wish to see in the world.” In the age of algorithms, that change begins with each of us — in every click, every conversation, and every choice.

. . .

References:

- Gandhi, M.K. (1927). Truth is God.

- Gandhi, M.K. (1928). “Anger and intolerance are the enemies of correct understanding.”

- Gandhi, M.K. (1930). “Restraint is the highest form of strength.”

- Gandhi, M.K. (n.d.). The Story of My Experiments with Truth.

- Parel, A.J. (2006). Gandhi’s Philosophy and the Quest for Harmony.

- ● Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You.

- Acharya, S. (2018). “Revisiting Gandhi in the Information Age.”

- Acharya, S. (2024). “Restraint in the Age of Stimulation: Gandhi and the Digital Mind.”

- Nanda, B.R. (2020). Gandhi and Modernity.

- Saraswat, P. (2025). “Digital Kindness is Modern Ahimsa.”

- Srivastava, N. (2025). “Gandhi in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.”

- Saraswat, P. (2025). “Ethics and Self-Reliance in Digital India.”