Photo by Kieran on Unsplash

In a country where vending machines can serve hot meals and humanoid robots greet guests at hotels, it may come as a surprise that a centuries-old practice involving carved seals still governs much of Japan’s official and daily life. This practice is the use of hanko, also known as inkan, a personalized stamp that functions as a signature. Used to approve contracts, bank transactions, and even mail deliveries, these seals are an intrinsic part of Japanese bureaucracy and identity.

While most of the world has long embraced handwritten or digital signatures, Japan’s continued reliance on hanko reflects a deeper cultural philosophy, one that prioritizes formality, tradition, and the physical imprint of a person's commitment.

Historical Roots of Hanko

The tradition of using seals in Japan began almost two thousand years ago. The first known instance occurred in 57 AD, when a gold seal called "King of Na gold seal" was gifted by China’s Emperor Guangwu of Han to the ruler of Nakoku. This symbolic gesture not only cemented diplomatic ties but also introduced the concept of official seals to Japan, drawing direct influence from established Chinese customs.

Initially, seals were symbols of imperial power and government authority. The aristocracy and high-ranking officials used them for important state affairs and decrees. Over the centuries, their use trickled down to the samurai class, who used them to sign land agreements, letters, and feudal documents. By the Edo period (1603–1868), even merchants and artisans had adopted the use of hanko for commercial and legal documentation.

The Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century played a pivotal role in institutionalizing hanko usage. In 1873, the Japanese government passed laws requiring citizens to register a personal seal for legal recognition. This codification transformed what was once a feudal and elite custom into a nationwide requirement, linking personal identity with an official, tangible object.

Types of Hanko

Today, most Japanese people own more than one hanko, each tailored to a specific aspect of life. These are not merely convenience tools, they carry varying levels of legal weight and social formality.

1. Jitsuin

The jitsuin is the most significant seal a person can own. It is officially registered at the local municipal office (yakusho), and it is necessary for high-stakes transactions such as buying property, registering a business, or taking out a substantial loan. The design of a jitsuin is unique and follows strict standards to prevent forgery.

2. Ginkō-in

This is the seal used exclusively for banking. When a person opens a bank account in Japan, they must register a ginkō-in with that institution. It acts as a form of identity verification when authorizing withdrawals, transfers, or changes to the account.

Though not always as strictly regulated as the jitsuin, the ginkō-in is crucial to managing one’s finances. Losing it can result in the temporary freezing of accounts until proper verification is re-established.

3. Mitome-in

This is the everyday seal used for routine, low-risk tasks such as acknowledging receipt of packages, signing internal work documents, or minor household paperwork. It is usually a mass-produced item, often carrying just the surname, and is not registered with any authority.

People might have multiple mitomes lying around at work, at home, and even in handbags, much like someone might carry pens. Despite its informal nature, its presence signifies acknowledgment or agreement.

4. Gagō-in

Used primarily by artists, poets, and calligraphers, the gagō-in is a seal that represents an artistic or pen name rather than a legal identity. It is typically stamped in red ink on artworks, much like a painter signs their canvas.

These seals are often crafted with aesthetic beauty in mind and are considered a final flourish of the artist’s expression. They lend a sense of authorship and cultural prestige to creative works.

Craftsmanship and Cultural Significance

Behind each hanko lies a world of meticulous craftsmanship and deep-rooted cultural symbolism. Traditionally, hanko are carved from a range of materials such as boxwood, wild cherry wood, buffalo horn, soapstone, and even ivory—materials that were once considered luxurious and symbolic of one’s social status. In recent years, more affordable or durable alternatives like acrylic, plastic, and titanium have become popular, especially for everyday or business use. The choice of material often reflects the purpose of the seal: personal, professional, or ceremonial.

The red ink used for stamping, called shuniku, is equally special. Unlike regular ink, shuniku is a paste-like mixture traditionally made from vermilion, a red pigment derived from cinnabar (mercury sulfide). It is known for its durability and resistance to fading, making it ideal for long-term preservation of signatures and stamps.

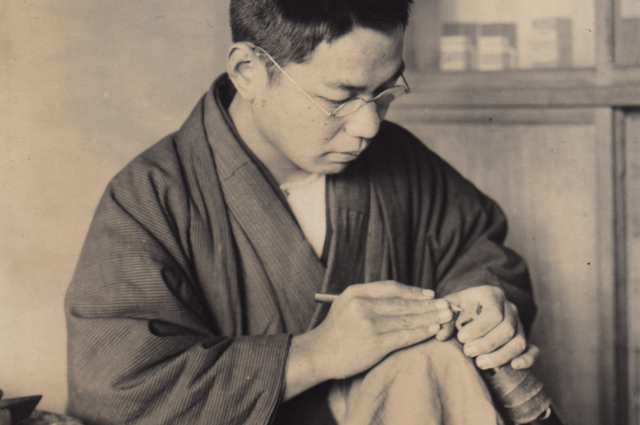

The characters on a hanko are usually inscribed in tensho, an ancient seal script, which makes them both unique and difficult to replicate. This adds a layer of security and artistic beauty to the stamp. Master carvers, known as hankō-shi, can take hours or even days to carve a single seal by hand, often treating the process with spiritual or ceremonial care.

Symbolically, hanko represents more than just identity, they embody the weight of a person’s promise or approval. In a collectivist society like Japan’s, where mutual trust and accountability are paramount, the act of stamping one’s seal signifies a deep, conscious commitment. Unlike a quick scribble of a signature, the use of hanko carries a sense of gravity and formality.

What do People think?

Public opinion in Japan about the hanko system is divided between reverence for tradition and a desire for modernization. For many, especially among the older generation, hanko is more than just a stamp; it’s a cultural artifact that signifies trust and deliberate intent. An elderly resident of Yokohama reflected on its significance by saying, “You stop and think before you stamp. That’s when you make a big decision like signing a marriage or divorce contract. It carries emotional weight.”

However, not all feel the same attachment. Criticism of the hanko system has grown, especially among the youth and working professionals who view it as outdated and inconvenient in today’s fast-paced digital world. An anonymous 28-year-old Tokyo-based graphic designer told: “Why do I need to go through a formal stamp just to approve an internal email? It’s 2023, not the Edo period”. Another example is university students applying for part-time jobs or internships. They often face delays and complicated paperwork because some employers still demand in-person hanko stamping for contracts.

Hanko in the Digital Age

As the world moves towards digitization, Japan's dependence on hanko has become both a cultural hallmark and a bureaucratic bottleneck. During the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work highlighted how inconvenient and outdated the practice could be, employees often had to travel to offices just to stamp documents, halting workflow and productivity.

Recognizing this, the Japanese government began taking steps to modernize administrative processes. In 2020, the Digital Agency was formed with a mandate to reduce red tape, and one of its goals was to minimize the mandatory use of hanko. Over 15,000 official procedures have since been revised to no longer require them.

Despite these changes, complete digitization is met with resistance. Many business owners, civil servants, and older generations remain attached to hanko for its cultural and perceived legal authenticity. Electronic signatures, though legally recognized, are often viewed with skepticism and lack the tangible, ceremonial feel of pressing a seal into red ink.

To bridge the gap, hybrid solutions have emerged. Digital hanko services replicate the appearance of physical seals while incorporating encryption and identity verification. These innovations suggest that while hanko may evolve, their symbolic value will not be easily replaced.

In Japan, where tradition and technology coexist in harmony, the hanko is more than a stamp, it is a cultural artifact, a statement of identity, and a conduit of trust. While modern times may demand swifter and more efficient systems, the enduring presence of the hanko speaks to Japan's deep reverence for ritual and history.

As reforms push for digital alternatives, the nation stands at a crossroads: should it abandon a centuries-old practice in the name of progress, or preserve it as a meaningful link to its cultural roots? The answer may lie not in choosing one over the other, but in finding a respectful integration of both. The hanko may lose its bureaucratic dominance, but its legacy as a symbol of responsibility, artistry, and cultural continuity is likely to remain stamped on Japan’s identity for generations to come.