Photo by Abhyuday Majhi on Unsplash

“A brush in hand, a voice online -

They sketch dissent in bold design.

From rangolis to reels, their stories ignite,

Turning quiet streets into canvases of fight."

I. Introduction

In the cacophony of slogans, barricades, and breaking news alerts, Indian protest spaces today are increasingly alive with color, rhythm, and creativity. Hand-painted posters flutter next to portraits of revolutionaries. Spoken-word poets draw cheers like rockstars. Memes spread faster than manifestos. And amid all this, art becomes action.

This is not a new phenomenon, but it is undergoing a radical transformation. In what can be termed the aesthetics of protest, the language of resistance in India is increasingly visual, poetic, performative, and digital. No longer confined to pamphlets and marches, dissent is now sung, painted, danced, and streamed on social media.

From the iconic sit-in at Shaheen Bagh to the satirical sketches during the Farmers’ Protest, from resistance performances in Manipur to feminist murals in Kerala, creativity has become the heartbeat of contemporary Indian protest. This article explores how artistic expression and digital innovation have reshaped the grammar of resistance in India, making it more inclusive, participatory, and deeply affective—even as the space for dissent shrinks.

II. Historical Context of Protest in India

India has long known the power of protest art. During the freedom movement, Rabindranath Tagore’s songs, Subramania Bharati’s fiery poems, and Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s plays were as potent as pickets and petitions. The Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), founded in 1943, pioneered the use of street theatre as socialist expression, with members like Balraj Sahni and Kaifi Azmi.

During the Emergency (1975–77), underground pamphlets and wall graffiti became subtle signs of resistance. Later, the Dalit Panther movement in Maharashtra used poetry and literature—such as the works of Namdeo Dhasal—to assert Ambedkarite pride against upper-caste hegemony. Protest posters with Gauri Lankesh’s quotes or graffiti reading “Jai Bhim, Lal Salaam” often referenced this enduring legacy.

Today’s aesthetic protests inherit from this legacy but also build on newer tools and sensibilities—digital fluency, hybrid identities, and performative politics. These forms do not merely accompany protests; they are the protest.

III. Visual Art and Murals in Protest Spaces

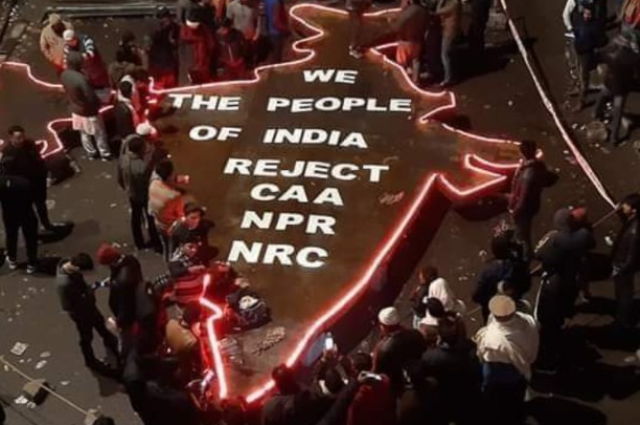

Perhaps the most visually compelling instance of protest art in recent memory was the Shaheen Bagh movement of 2019–2020. The Muslim women of Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh transformed their protest site into an open-art gallery. Wall after wall was covered with portraits of B.R. Ambedkar, Mahatma Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, and Urdu couplets by Faiz Ahmed Faiz like “Hum Dekhenge,” which became the unofficial anthem of resistance.

Zainab, a 62-year-old protester, recalled painting the Indian flag with schoolchildren every evening. “It wasn’t just about the CAA. We were claiming our space as Indians through color and brush,” she told The Wire.

In 2023, students of Sikkim University painted a massive mural protesting racial discrimination against northeastern Indians after an incident in Delhi. They used traditional Lepcha patterns to underscore identity pride.

In Kozhikode, Kerala, feminist collectives covered the walls around the Kozhikode beach with graffiti quoting Savitribai Phule and Audre Lorde, protesting gender-based violence after the custodial death of a trans woman. The initiative, named Wall of Grief, Wall of Power, drew over 50 volunteers, including grandmothers and teenage students.

In 2024, a group called Brushes of Dissent in Bengaluru used augmented reality (AR) murals to embed digital stories into protest art. A viewer with a smartphone could scan the mural and watch testimonies from survivors of caste violence.

Visual art in protests is more than decoration—it is a tool of re-imagining and decolonizing space. In this sense, it echoes Michel Foucault’s notion of heterotopias, spaces that exist outside of everyday life and create alternative realities. A protest mural or a guerrilla art piece disrupts the status quo and redefines the meaning of public space. When students at Shaheen Bagh transformed the protest site into an open-air gallery, they were not merely making a statement—they were rewriting the very concept of “public” in the Indian context.

The power of visual art in protest lies in its accessibility and universality. Unlike written texts, which can be restrictive due to language or literacy barriers, art bypasses these limitations and directly engages the viewer’s senses. According to the philosopher Henri Lefebvre, the production of space is inherently political. Graffiti, murals, and street art on protest walls become a critique of dominant narratives—especially when placed in spaces of power, like government buildings or temples. Thus, in many ways, the street becomes a “resistance gallery,” with every wall a canvas for both the artist’s and the community’s political imagination.

IV. Performance, Theatre, and Street Play

Performance art has become a resilient form of expression. Street plays, or nukkad nataks, remain staples on campuses and in city squares. In 2023, students at Jamia Millia Islamia revived Habib Tanvir’s Charandas Chor to critique the hypocrisy of governance under populism.

In Tamil Nadu, the theatre group Koothu Kalai Kuzhu reinterpreted classical Therukoothu performances to dramatize the struggles of fisherfolk resisting coastal eviction under tourism development policies. Their rendition titled The Sea Will Speak, combined folk music, dance, and interviews.

At the Manipur Women’s Sit-In of 2023–24, Meira Paibis (women torchbearers) sang folk ballads of grief and resilience while seated in traditional attire at protest vigils. Their resistance wasn’t just verbal—it was deeply performative, combining lament, costume, and dance.

At Hyderabad University in 2025, students used flash mobs during lunch breaks to perform sequences from Safdar Hashmi’s Halla Bol, marking his 36th death anniversary.

Performance art in protest draws from Judith Butler’s notion of performative politics, where acts of resistance are not just expressions of dissent but constitute new ways of being in the world. Butler’s theory suggests that identity is performed and can be re-performed, which is especially relevant in protest spaces. A protester dressed in traditional attire or performing a nukkad natak isn’t merely symbolizing resistance—they are actively creating a new political subjectivity through their performance.

Theatre and street plays are particularly powerful because they create a “live” interaction with audiences, often leading to an emotional investment. Augusto Boal’s concept of Theatre of the Oppressed emphasizes the role of spectators as active participants. By engaging them physically and emotionally, these performances challenge the spectator’s complicity in the status quo and inspire collective action. In the 2024 Tamil Nadu protest, folk traditions like Therukoothu became an outlet for local grievances, allowing performers to critique authority while simultaneously affirming their cultural identity. The stage, much like the street, becomes a site of both resistance and reinvention.

V. Digital Protest and Meme Culture

With over 880 million internet users, India’s protest culture has increasingly moved online. Memes, reels, digital posters, and hashtags now drive engagement and solidarity. During the 2024 Supreme Court hearing on same-sex marriage rights, queer creators on Instagram ran the viral campaign #LoveIsLegal, accompanied by pastel-toned animated illustrations.

Satirical memes mocking political figures, like those created by The People’s Meme Collective, went viral during the 2023 NEET-UG paper leak controversy, with memes juxtaposing exam stress with government indifference.

Following the Gujarat textbook censorship row, students in Ahmedabad released a satirical zine titled Rewritten Histories, featuring comic-style critiques of state narrative manipulation.

Platforms like @theindianfeminist and @artedkar use satire, infographics, and short-form videos to make complex protest issues accessible. Their visual languages, borrowed from pop culture and folk symbolism, embody a hybrid resistance.

Memes combine humor, irony, and sharp critique, making them perfect for political engagement, especially among younger generations fluent in digital languages. The meme “This is fine” with a cartoon dog sitting in a burning room has become a classic symbol of passive resistance—reminiscent of how the average citizen might feel about certain political decisions, yet powerless to act. Through a single image and a few words, memes capture a sense of collective frustration while offering a relatable, often hilarious commentary on complex issues.

Memes don’t just react—they shape the narrative. They spread quickly, crossing social and geographical boundaries, allowing protests to go viral with a speed that traditional methods of resistance can’t match. A meme might even start as a funny, satirical quip but rapidly become a rallying cry for collective action. In this digital era, memes have transformed protest into something more immediate, interactive, and deeply embedded in everyday online culture, reshaping not only how we resist but how we envision the future of political activism. So, the next time you find yourself laughing at a meme, remember—sometimes, resistance looks like a meme of a dog, sitting in a burning room, wearing a rainbow flag.

VI. Literature, Poetry, and Spoken Word

Poetry and spoken word are ancient tools of resistance, now revived with vigor. From Faiz's Hum Dekhenge to Imtiaz Dharker's They’ll Say: “She Must Be From Another Country”, poets across India continue to fight erasure through words.

Kolkata-based poet Sumana Roy’s 2023 collection Silence Between Notes was a poetic documentation of farmer suicides and climate grief. In Bhopal, a reading from the banned works of Mahasweta Devi was held under a banyan tree, reminiscent of the storytelling circles of pre-modern India.

In 2025, a collective in Pune called Verse Resistance hosted a 24-hour poetry livestream in solidarity with Iranian women protesters, blending South Asian feminist writing with global solidarity.

In 2023, The Protest Poem Project, an academic collaboration between Delhi University and Jawaharlal Nehru University, analyzed over 700 protest poems written in Indian languages since 2019. It revealed that over 60% of these poems were authored by first-time writers, many of them women and queer individuals, indicating the radical democratization of literary resistance. The anthology No Nation for Women: Voices of Dissent (2024) edited by Roshni Menon, brought together poems and testimonies from acid attack survivors, Dalit students, and Kashmiri mothers. It sold over 12,000 copies in two months and was adapted into a touring spoken word production across college campuses.

At a 2024 Jaipur Literature Festival offsite event, Kashmiri poet Ather Zia read her poem The Veil Is a Flag, which drew standing ovation and tears. Zia remarked, “Poetry is our last homeland.” Spoken-word artist Shakti Rao’s viral piece License to Live—a scathing critique of Aadhaar surveillance—has over 1.3 million views on YouTube.

Even in prison, protest poetry thrives. In 2025, letters smuggled out from Tihar Jail by incarcerated student activist Neha Jain included haikus about isolation and resilience. These were later published in Bars and Verses, a slim volume that became a symbol of undying literary dissent.

Protest literature and poetry often operate as counter-narratives, challenging the dominant discourses of the state and mainstream media. In line with Michel de Certeau’s concept of tactics, protest poetry finds ways to speak subversively without direct confrontation. Poetry, with its metaphorical power, allows protestors to “speak in riddles,” engaging in a form of resistance that cannot be easily co-opted or censored by the state. Each protest poem, whether a slam piece or a spoken-word performance, is an act of reclaiming the means of representation.

Poetry’s role in protest also reflects Henri Bergson’s idea of duration—the process of experience, memory, and collective temporality. A protest poem, particularly one with a rhythm or cadence, creates a sense of continuity that transcends the immediate moment of protest, allowing its message to reverberate long after the protests have ended. The resonance of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge or Kafeel Ahmed’s viral speech lies not just in their meaning, but in their capacity to evoke feelings, memories, and an ongoing sense of collective struggle. In this way, protest poetry is not just about the present—it is about imagining the future through the aesthetics of language.

VII. Gender, Queerness, and the Aesthetic of Protest

Women and queer individuals have led many creative protests. The 2023 Sitapur Girl’s March, which protested a rise in school surveillance and dress code policing, was choreographed like a flash mob with synchronized folk dance and rangoli art.

In Hyderabad, Dalit queer collectives used kolam designs outside government offices in 2024 to protest the denial of scholarships to trans students. Each kolam had embedded QR codes linking to testimonies.

At the 2025 International Women’s Day March in Bengaluru, the collective Kaali Kathas performed a theatrical protest dressed as goddesses with ironic placards like “Kali is watching patriarchy crumble.”

In Delhi, a 2023 pride march featured drag performances with protest messages like “My identity is not a crime” and live body painting with the Preamble of the Indian Constitution.

The intersection of protest and gender is best understood through the lens of bell hooks’ concept of feminist aesthetics. For hooks, aesthetics is not just about beauty but about how beauty and identity are formed in the context of power and resistance. The use of femininity and queerness in protest is a direct challenge to patriarchal power structures that often police the body and identity. When women and queer individuals perform their resistance through art, dance, and fashion, they are subverting the traditional notions of who gets to be heard and who gets to hold space.

Drawing from Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity, these protests articulate a refusal of binary gender norms and demand a rethinking of identity within the political sphere. For example, the Pride March in Delhi or the Kaali Kathas group in Bengaluru foreground the performative dimension of protest, where resistance is as much about challenging the idea of gender as it is about challenging the state. Through dress, choreography, and poetry, these protests provide a sensory experience that not only critiques but also reimagines gender, moving beyond mere critique into the realm of creation.

VIII. Censorship, Crackdowns, and Resilience

Creative dissent often invites suppression. In 2023, Mumbai Police painted over a protest mural on climate change near Marine Drive. The mural depicted submerging buildings and burning trees and was labeled 'anti-development.'

In 2024, theatre activist Anirban Bhattacharya was detained for his satirical play The Elephant in the Room, which lampooned censorship. The detainment led to city-wide "Art Not Arms" events in Mumbai, Kolkata, and Lucknow.

Anonymous collectives like Verse Against Fascism distribute encrypted zines and host QR-based digital art galleries that pop up on college campuses for 24 hours before disappearing.

The struggle against censorship can be theorized through the lens of Giorgio Agamben’s idea of the state of exception, wherein authoritarian regimes suspend the rule of law and normal rights under the guise of maintaining order. The resistance to censorship is not just a legal or political struggle but a fight for the right to think and create. In the face of censorship, protest aesthetics become an act of resilience, creating alternative spaces of expression that defy governmental control.

Artistic resistance, as Agamben’s theory suggests, is often about creating “zones of freedom” within an otherwise controlled environment. Whether through graffiti or underground performances, these acts are about reclaiming spaces of creative freedom in moments of repression. The reaction to the crackdown on murals or the detention of theatre artists highlights this complex dynamic—where art becomes an active resistance to the very notion of “order” imposed by the state. Protest art, in this sense, is an act of rebellion not just against a specific policy but against the overarching system of control.

IX. The Philosophical and Political Stakes

Art, as Jacques Rancière argues, reconfigures the sensory. Protest aesthetics in India create an alternative sensory politics—where the disenfranchised are not just seen and heard but felt. In Protest: By Design (2023), Ruchi Kaushal describes how protest aesthetics create counter-publics.

The affective power of protest is also evident in the viral speech by activist-poet Kafeel Ahmed at JMI (2023), who said, “They want silence. We will answer with song. They want obedience. We will answer with art.”

Protest aesthetics transcend mere symbolic opposition—they offer an alternative vision of politics. Drawing from Jacques Rancière’s notion of the politics of aesthetics, protest art in India becomes a tool for democratizing the very sensory experience of political life. Rancière argues that politics is not merely about policy or governance but about what is visible and audible in the public sphere. A protest, in his terms, disrupts the usual sensory hierarchy—what is seen, heard, and understood.

This notion is vital in understanding why aesthetic protest can be so powerful: it doesn’t just aim to disrupt public life; it seeks to reshape what is understood as political action. When activists use creative means—whether it’s performance, digital art, or literature—they are engaging in what Rancière calls the distribution of the sensible, offering an alternative sensory experience that challenges the dominant order of political representation. These aesthetic acts are thus political in the most profound sense: they make visible the invisible and give voice to the silenced.

X. Some Lesser-Known Examples

- In Nagaland (2024), Angami youth painted ancestral motifs on roads to protest land encroachment by the army.

- In Bhopal, gas tragedy survivors held a protest in 2023 with masks made from pharmaceutical blister packs, calling it “art from poison.”

- In Pushkar, camel herders staged folk puppet shows in 2025 to criticize tourism's impact on desert ecology.

- In Varanasi, temple sanitation workers performed Katha Natak about caste hierarchy using traditional instruments and digital projection mapping.

XI. Conclusion: The Future of Protest Aesthetics in India

The aesthetics of protest in India have evolved beyond simple expressions of dissent into a profound reshaping of the political landscape. In a time when the very fabric of democracy is being tested, art, poetry, and digital creativity stand as a resilient counterforce.

What makes these expressions so powerful is not merely their ability to challenge the state or dominant power structures, but their capacity to shift the cultural and ideological narratives that govern society. As the poet Kabir famously said, "ज्यों की त्यों रखी, डाली न जाला," meaning, “What is placed within the heart remains unchanged, despite external forces.”

This sentiment resonates deeply with the current generation of protestors who, through their creative resistance, have not only held onto their values but have also redefined the meaning of justice, freedom, and equality in the modern Indian context.

In a country where traditional forms of protest are often met with harsh repression, the aesthetic becomes an act of reclaiming public space—not just physically but symbolically. The deeper significance lies in how these aesthetic practices, whether through art, poetry, or digital media, create a new language of resistance that speaks to the collective memory and cultural identity. They are shaping a movement where the imagination is not limited to merely opposing the status quo, but in proposing alternative ways of living, thinking, and engaging with the world. As the digital age continues to redefine how we communicate, the aesthetics of protest become a vital tool not just for change, but for the survival of democracy itself.