In 2018, a blurry, baroque-style portrait titled "Edmond de Belamy" sold at Christie’s auction house for over $400,000. The artist? Not a human, but a generative adversarial network trained on thousands of classical paintings.

The world was stunned—not just by the artwork, but by the unsettling idea it provoked: Had a machine just entered the pantheon of artists? Was this an algorithm merely mimicking form, or was it the first spark of machine creativity? In a world where machines “dream” in code and pixels, we’re forced to confront an unfamiliar frontier: the soul of creativity in a silicon mind.

The lines between art and code, muse and model, are blurring. Can a machine dream? Can it imagine, invent, or improvise? To answer that, we must first unpack what creativity really means. Most scholars agree that it’s not just about novelty, but about the fusion of originality, value, and intent.

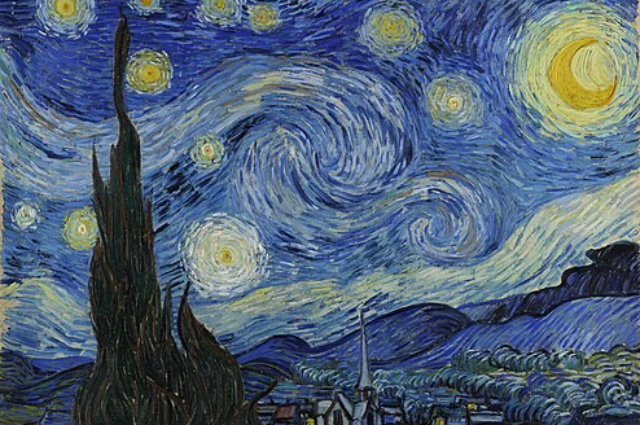

Enter generative AI—a suite of tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, DALL•E, and AIVA—that can write poetry, paint like van Gogh, score orchestras, or mimic your favorite author in milliseconds. Their outputs often dazzle, inspire, even unsettle. But behind the curtain lies a cold, calculative engine: a machine learning model churning through vast oceans of data. Is that enough to call it creative?

This essay argues no. While AI can simulate creative processes—and even surprise us with the beauty of its output—it lacks intentionality, self-awareness, and emotional context. True creativity is not just the arrangement of pixels or phrases, but a deeply human act of meaning-making, driven by consciousness and purpose.

As we unravel the philosophical, technological, and ethical layers of this debate, one thing becomes clear: AI may help us reflect on our own creativity—but for now, and perhaps forever, it dreams only in borrowed visions.

A human hand painting vs. a Robotic arm mimicking it (Source AI)

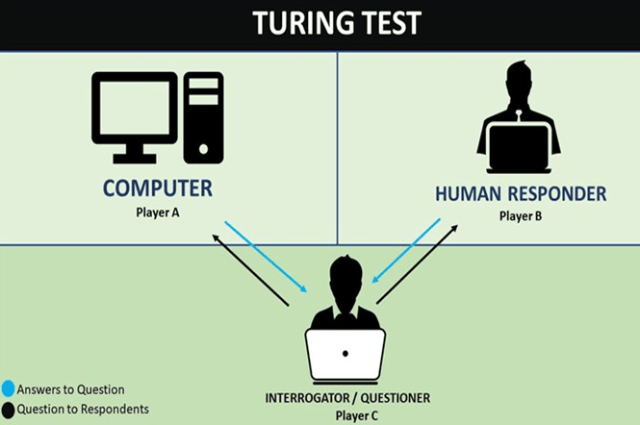

A Brief History of Machine Creativity

Long before machines composed music or painted portraits, one man dared to ask a deceptively simple question: Can machines think? In 1950, British mathematician Alan Turing challenged the world with his famous Turing Test—an experiment not of wires and gears, but of mimicry and meaning. If a machine could hold a conversation indistinguishable from a human, could we say it was intelligent? Turing’s inquiry may have seemed like science fiction at the time, but it cracked open a philosophical Pandora’s box: if machines could simulate thought, could they one day simulate creativity?

Fast forward to the 1970s, and machines were beginning to pick up brushes—literally. British artist Harold Cohen created AARON, one of the first AI programs capable of producing visual art. AARON didn’t just reproduce existing images; it developed its own stylistic evolution over time. Though devoid of feelings or intentions, its sprawling digital paintings raised eyebrows and eyebrows alike: could this machine be said to create?

Around the same period, music professor David Cope introduced EMI—Experiments in Musical Intelligence—a software that analyzed classical compositions and generated new ones in the same style. EMI once fooled music scholars into thinking they were listening to undiscovered works by Bach. What stirred more than applause, however, was unease: if a machine could fake genius, what did that say about our own?

These early ventures were rule-bound and logical, like clever puzzles solved by elaborate instructions. But the modern age of AI ushered in a shift from syntax to symphony—from commands to learning. Deep learning changed the game. Instead of explicitly programming creativity, we began feeding machines mountains of data and letting them teach themselves the patterns.

This evolution reached a milestone with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)—neural duels where one network generates content and another critiques it. Think of it as an eternal creative rivalry, where the generator strives to fool its counterpart. From haunting artworks to lifelike deepfakes, GANs birthed a new age of synthetic originality.

Meanwhile, Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and GPT-4 emerged as linguistic juggernauts. Trained on billions of words, they began generating essays, scripts, jokes, and sonnets. Not as clunky regurgitations, but as fluid, context-aware outputs that sometimes astounded even their developers. These weren’t mechanical parrots—they were statistical improvisers, wielding grammar and metaphor like digital bards.

Yet despite their growing sophistication, the elephant in the server room remains: are these systems truly being creative—or just exceptionally good at imitation? As we trace the arc from Turing’s question to today’s generative marvels, we find ourselves at a strange crossroads. Machines can now mimic much of what we once considered uniquely human. But the soul—the messy, emotional, purpose-driven chaos that defines human creativity—remains elusive.

We’ve built machines that can dazzle. But whether they can dream is still an open question.

Case Studies of AI Creativity

From the hallowed halls of Christie’s to the synth-heavy corridors of pop music studios, AI is no longer confined to code. It’s performing. Creating. Publishing. But is it expressing? To probe this, let’s explore real-world case studies across three realms: visual art, music, and literature.

Visual Art: When Machines Hold the Brush

In 2018, the now-infamous Portrait of Edmond de Belamy became the poster child of AI art. Created by Paris-based collective Obvious using a GAN trained on 15,000 portraits from the 14th to 20th centuries, the portrait was blurred, uncanny, oddly soulful—and entirely algorithmic. Its sale for over $432,000 stunned the art world. But was it admiration for the portrait, or for the audacity of a machine artist?

Then came Midjourney, DALL·E, and Stable Diffusion—platforms that let anyone generate surreal, fantastical, or hyper-realistic images from simple text prompts. From “an astronaut riding a horse in a nebula, in the style of Van Gogh” to haunting dreamscapes worthy of a MoMA exhibit, these tools democratized the act of “making art.” Yet, behind the visual spectacle lies a question: are these works born from imagination—or just recombinant mimicry of existing styles?

Midjourney-generated art (astronaut in Van Gogh style)

Art critics remain divided. Some hail these tools as the next evolution in visual culture; others liken them to aesthetic plagiarism at scale. After all, does sampling a thousand van Goghs and blending them into a new frame constitute originality—or is it just a statistical remix?

Music: AI as Composer and Collaborator

In 2016, an AI music composer named AIVA (Artificial Intelligence Virtual Artist) earned a spot on the list of officially recognized composers with SACEM, the French music rights society. AIVA has since composed soundtracks for films, ads, and video games. Its compositions are atmospheric, emotive, and—sometimes—startlingly human.

Similarly, American singer Taryn Southern released I AM AI, an entire pop album co-written with AI tools like Amper Music. Her tracks are catchy and sonically polished—but what’s missing is the story behind the song. There’s no heartbreak, no lived experience, no long night in the studio agonizing over a chord. It’s the form of art without the journey.

Music, at its best, captures the ineffable—grief, joy, protest, longing. Can an AI, which feels nothing and knows no silence between notes, ever compose a true anthem?

Literature & Language: When Words Are Weaved by Code

Language is often seen as the final frontier of human creativity—where logic dances with emotion, and ideas birth new worlds. Yet AI has leaped this frontier too. Tools like GPT-4, Sudowrite, and ChatGPT now write poems, pen essays, draft short stories, and even co-author novels.

Some outputs border on brilliance. AI can craft haikus, simulate Shakespearean soliloquies, or write eerily convincing horror stories in the style of Lovecraft. In 2021, an AI co-authored an entire screenplay that was later turned into a short film. These aren’t just fragments—they are structurally complete, linguistically coherent, and often imaginative.

But again, intention is absent. When GPT-4 writes a breakup poem, it doesn’t ache. When it describes a dying planet, it doesn’t mourn. Its metaphors shimmer, but they do not originate from lived memory. They are echoes, not voices.

Even when AI assists human writers—as with Sudowrite’s plot suggestions or character development tools—it acts more like an amplifier than a muse. It can help shape, accelerate, or refine—but rarely conceive.

So, what connects all these cases? From painted portraits to symphonies to short stories, AI has proven it can generate—sometimes beautifully, sometimes eerily—artifacts that resemble creative work. But the key word is resemble. At the heart of each output is not an emotional impulse or philosophical drive, but a predictive engine mapping probability distributions.

The question is no longer can AI create, but rather: what does it mean when it does? Are these works merely sophisticated predictions based on learned data—or are they emerging expressions of a new kind of intelligence?

So far, the answer leans toward the former. AI outputs are mirror images of our own creative corpus—stunning, yes, but derivative. The mirror can be crystal clear, but it doesn’t dream.

IV. Philosophical and Cognitive Dimensions of Creativity

What is creativity, really? Is it just the clever shuffling of ideas, or something far deeper—a spark that ignites within the tangled web of human experience, consciousness, and emotion? AI’s rise forces us to confront these questions head-on.

Imagine a painter staring at a blank canvas. Their brush strokes are not random; they carry memories of past loves, dreams, heartbreaks, and wild hopes. Creativity is not just a process; it’s a profoundly intentional act—a dialogue between the artist’s inner world and the outside one. But can a machine, cold and unfeeling, ever have such a conversation with itself?

Margaret Boden, a trailblazer in the science of creativity, breaks it down into three kinds: combinational (mixing old ideas in new ways), exploratory (pushing boundaries inside a known space), and transformational (smashing the rules to create something wholly new). AI can remix and explore—sure. It can churn out variations on a theme until they shimmer with novelty. But to transform? To rewrite the playbook? That seems out of reach.

Why? Because transformational creativity requires more than data crunching. It demands self-awareness—a consciousness that reflects on its own work, questions its meaning, and dares to dream beyond the familiar. It requires values, a purpose, even rebellion. And machines have none of that.

Cognitive science paints creativity as a dance of mind and body—emotions, memories, sensory experiences, culture, and even the beat of a heart all intertwine. It’s messy, irrational, and deeply personal. AI, on the other hand, is an elegant calculator, spinning probabilities but without feeling, without a soul.

Creativity is often born from need—the need to express pain, joy, resistance, or hope. It’s a story told to make sense of chaos. But AI doesn’t need anything. It does not hunger, suffer, dream, or rebel. It simply predicts what might come next based on patterns it has seen.

Philosopher John Searle’s famous “Chinese Room” thought experiment reminds us: AI manipulates symbols, but it doesn’t understand them. It’s like a musician playing notes without hearing the melody.

Does this mean AI’s creative output is worthless? Absolutely not. Instead, it reframes AI as a powerful mirror—reflecting human creativity back to us in strange, unexpected ways. It becomes a collaborator, a tool that can amplify and inspire human imagination, but not replace the messy magic that is uniquely ours.

So, in a world where machines can paint, compose, and write, creativity is no longer a solitary human throne but a shared landscape—one where human passion and machine logic collide, sparking new conversations about what it truly means to create.

The Human-AI Co-Creative Future

If AI can’t truly create on its own, then what role does it play in our creative futures?

Let us picture a jazz duo: one musician improvising soulful melodies, the other providing rhythmic backing. Neither dominates; each listens, responds, and inspires the other. This is the emerging reality of human-AI co-creation—where AI is less a rival genius and more a creative amplifier, a tool that expands our artistic horizons.

The uncommon jazz duo (Source: AI)

Musicians like Holly Herndon have already embraced this future. Her album PROTO features an AI “baby” called Spawn, co-composed and trained alongside human musicians. Rather than replacing the artist’s vision, Spawn becomes an unpredictable collaborator, introducing sounds and rhythms that surprise and push boundaries. It’s a new kind of creative partnership—one where human intuition meets algorithmic novelty.

In visual art, pioneers like Mario Klingemann use AI to explore the edges of perception, generating surreal, dreamlike images that challenge our assumptions of what art can be. For Klingemann, AI isn’t a mere brush; it’s a creative partner with its own kind of “vision,” capable of sparking fresh ideas through unexpected glitches and patterns.

This collaboration isn’t limited to elite artists. The rise of prompt engineering—the craft of designing precise instructions to coax the best output from AI models—has become a new form of literacy. Knowing how to “talk” to an AI, how to shape its responses, is now a vital creative skill. Writers, designers, marketers, and educators are learning to co-pilot AI like a creative compass, steering machines through oceans of possibility toward inspired shores.

But this future isn’t without tensions. As AI grows more capable, questions arise: Who owns the art created by human-AI teams? When an AI generates a striking image or haunting melody, who gets the credit? When AI generated the Ghibli art, did creativity impinged on someone’s rights? And crucially, how do we ensure that the human spirit remains at the heart of creativity, not eclipsed by code?

These concerns remind us that creativity is not just about the final product—it’s about agency, intention, and the stories behind the work. AI can generate, but it cannot feel the thrill of discovery or the agony of doubt that shapes a human artist’s journey.

Ultimately, the co-creative future is a space of possibility—a place where human and machine intertwine in new, uncharted ways. It invites us to rethink authorship, to embrace hybrid identities, and to celebrate creativity as a shared adventure.

In this unfolding story, AI is less a challenger to our creative throne and more a new kind of muse—one that speaks in algorithms but listens with us, sparking fresh dreams in the ever-expanding tapestry of human imagination.

Ethical and Legal Challenges

In the age of AI-generated art, music, and literature, the question isn’t just can machines create—but who owns what they create? As AI’s artistic capabilities expand, so too do the ethical and legal thickets surrounding them. We’re not just witnessing a technological revolution—we’re navigating a moral and intellectual property minefield.

When Portrait of Edmond de Belamy sold at Christie’s, the algorithm behind it made headlines. But the real authors—those who trained the AI, curated the dataset, tweaked the code—remained in a legal gray zone. Who, exactly, was the artist? The developers? The algorithm? The collective corpus of thousands of human painters whose works trained the model? Copyright law, designed for the brushstroke and the pen, now fumbles to grasp the keystroke and the neural net.

At the heart of this confusion is a profound dilemma: can a machine own its creation? The answer, legally and philosophically, is no—AI lacks personhood. Yet if the machine can’t claim ownership, does it automatically transfer to its human operator? Or does it rightfully belong to the thousands of creators—painters, poets, musicians—whose original works were ingested, uncredited, into the model’s training data?

This leads us to a pressing ethical question: is AI-generated content built on plagiarism? Much of today’s generative AI is trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet, often without consent or attribution. That stunning AI-generated sonnet may be stitched from the voices of hundreds of human poets, whose work was never meant to be deconstructed into tokens and recombined without recognition.

And then there are the dark mirrors: deepfakes and voice clones, eerily realistic creations that can mimic celebrities, political figures, even our loved ones. These aren’t just tools for entertainment—they’re potential weapons of misinformation and identity theft. When an AI can fake a speech, forge an artwork, or resurrect a voice from the dead, what happens to trust, authenticity, and consent?

Artists, ethicists, and policymakers are now calling for greater transparency in AI systems. Demands for attribution frameworks, opt-out rights for creators, and regulation of training data are growing louder. Some advocate for “nutrition labels” for AI-generated content—disclosures that tell users what a model was trained on and whether the output is synthetic. Others push for entirely new legal categories to define and protect both human and AI-influenced works.

The creative world stands at an ethical crossroads. Without thoughtful safeguards, we risk a future where creativity is commodified, originality diluted, and artists erased. But with deliberate regulation and transparent practices, we might craft a new kind of authorship—one that honors both innovation and integrity.

After all, creativity—human or hybrid—shouldn’t just be about what we can make. It should be about what we ought to make, and the kind of world we want to imagine into being.

Certainly! Here's the Conclusion section based on your outline, written in an engaging and thought-provoking style that complements the rest of your essay:

Conclusion: The Mirage of Machine Imagination

AI is a mirror drawing inspirations (fragmented artworks), not an original dreamer (Source: AI)

As we trace the digital footprints of AI across canvases, concert halls, and computer screens, one fact becomes clear: AI can convincingly mimic creativity—but it does not originate it. Its works may dazzle with novelty and style, but they are built upon the scaffolding of human expression, remixed from oceans of pre-existing data. Like a skilled impersonator, AI learns the voice, the rhythm, the gesture—but it does not know why the song was sung in the first place.

At the heart of human creativity lies something machines cannot replicate: conscious insight, emotional depth, and the weight of lived experience. A human writes a poem not just with words, but with memory. A painter doesn't simply apply color—they translate longing, defiance, wonder. AI, however sophisticated, does not long, defy, or wonder. It doesn’t feel. It calculates.

Still, the future of creativity is not a zero-sum battle between human and machine. Rather than replacing artists, AI is reshaping the tools and processes through which art is made. Musicians use AI to compose harmonies they hadn’t imagined. Writers use it to overcome creative blocks. Visual artists wield prompts like brushes, engaging in a new kind of co-creation. The canvas is expanding—but the hand that holds the brush remains human.

Yet as AI grows more convincing, more prolific, and more accessible, we are left with a provocative question: If creativity becomes predictable—modeled, prompted, generated—does it still remain creative? When originality becomes an algorithm and surprise becomes a feature, do we risk reducing art to output?

In the end, perhaps the role of AI is not to dream for us, but to remind us what our dreams are made of. It can inspire, assist, even astonish, but the soul of creation still belongs to those who know what it means to suffer, to rejoice, to hope.

To be truly creative is not just to generate, but to mean.