India, an ancient civilisation of the world, has a very strong and intricate social hierarchy, much of which is based on the caste system. Even after modernisation, economic development, and constitutional safeguards, the caste continues to impact social relations, access to resources, and opportunities. The caste system is not only a residual feature; it is also an enduring and dynamic social phenomenon.

This essay explores the beginnings, composition, influence, and changing character of caste and social hierarchy in India.

Historical Origins of the Caste System

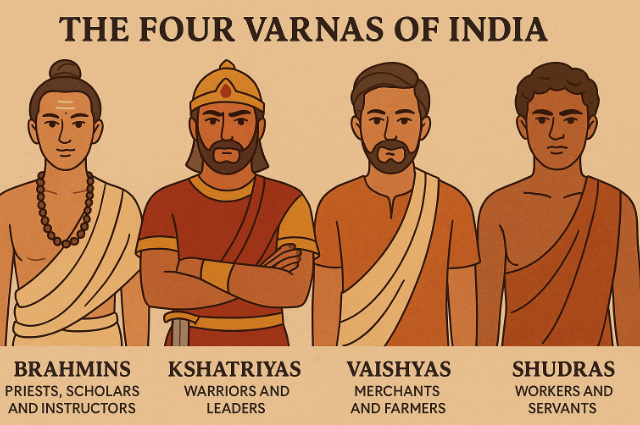

The Indian caste system dates back to ancient times. It is estimated to have started more than 3,000 years ago, in the Vedic era. The Rigveda mentions social stratification for the first time and speaks of the Varna system, which segmented society into four major groups:

- Brahmins – Priests, scholars, and instructors.

- Kshatriyas – Warriors and leaders.

- Vaishyas – Merchants and farmers.

- Shudras – Workers and servants.

Besides these classes, there were the so-called “Avarnas” or “untouchables”, later known as Dalits. They were regarded as being outside the social hierarchy and discriminated against heavily.

Whereas the more flexible Varna system developed over time, the Jati system—local, hereditary units—solidified. Every Jati had its distinct profession and regulations on marriage, diet, and social relationships, which resulted in a highly hierarchical and closed social hierarchy.

Caste and Religion

Although caste is directly linked with Hinduism, it has affected other Indian religions, such as Islam, Christianity, and Sikhism. Even though these religions have egalitarian ideals, Indian followers of the religions embraced caste-like traditions because of the widespread reach of the system in the subcontinent. This has created differences like Ashraf and Ajlaf among Muslims, or Dalit Christians and Dalit Sikhs, who are subjected to similar discrimination even after converting to other religions.

Caste and Social Hierarchy

India’s caste system in the past defined nearly every part of life:

- Occupation

Occupations were traditionally closely associated with caste. Brahmins were priests and scholars, and Dalits were confined to so-called “impure” occupations such as manual scavenging, working with leather, or cremation. - Social Status

Upper castes had privileges, education, and riches, whereas lower castes were typically landless, impoverished, and suppressed. Social mobility is practically nonexistent. - Endogamy

Caste determines marriage decisions to a great extent. Inter-caste marriages were not very common and socially stigmatised. Honour killings and ostracisation were—and still are—not unusual in instances of inter-caste marriages. - Access to Resources

Land, temples, and education were traditionally dominated by upper castes. Dalits and backwards castes were frequently debarred from temples, schools, and public wells.

British Colonial Impact

Under British colonial domination, the caste system was documented and solidified through census operations and administrative categorisation. The British formalised caste identities for administration purposes, which inadvertently cemented caste divisions. They also established western-style education and legal reforms, which allowed some lower castes to unionise and request rights.

Colonial policies at the same time benefited upper castes in employment and education, further cementing existing hierarchies.

Post-Independence Reforms and the Indian Constitution

At the time of India’s independence in 1947, the Indian Constitution’s creators understood the caste system’s oppressive character. Under the leadership of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit himself and the chief framer of the Constitution, the following measures were adopted:

- Abolition of Untouchability (Article 17)

- Right to Equality (Article 14)

Reservation Policies in education, employment, and politics for Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and subsequently Other Backwards Classes (OBCs)

Such affirmative action policies were initiated to correct historical wrongs and form a fairer society. And yet, caste discrimination did not vanish it evolved.

Caste in Modern India

Today, caste is present overtly and covertly:

- Education and Employment

Reservation policies have enhanced education and employment opportunities for marginalised communities. But the gains are lopsided. While some Dalits and OBCs have reached high echelons, the bulk of them are still economically and socially backwards.

Resistance from upper castes to reservations persists, at times spilling onto the streets in protest. In contrast, pressure to be included among the OBC groups has come from groups such as Jats, Patels, and Marathas, out of economic fears. - Politics

Indian politics is heavily dominated by caste. Political parties tend to woo certain caste groups on the basis of representation, subsidies, or welfare programs. Electoral strategy is heavily dependent on vote banks along caste lines.

Backwards caste and Dalit voters have been brought into play by regional parties in the Uttar Pradesh and Bihar states. Individuals such as Kanshi Ram and Mayawati have promoted Dalit identity into the political mainstream. - Urban vs. Rural Divide

In cities, the caste divisions are not overt but continue in the areas of housing, marriage, and work relationships. In rural environments, the caste hierarchies continue to remain deep-seated. Cases of violence, social boycott, and withdrawal of elementary rights are commonly found. - Social Mobility

Education and economic progress have permitted some upward mobility, but particularly amongst the “creamy layer” of Dalits and OBCs. Inequality runs very deep and persists. The fact that caste disadvantage is intergenerational implies that mobility is sluggish and uneven.

Caste Discrimination and Atrocities

Even with legal protection, caste-based violence and discrimination are still widespread. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) records thousands of cases annually under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

Some of the common methods of discrimination include:

- Refusal of entry into temples and public places

- Physical abuse and rape of Dalits

- Social boycott by dominant castes

- Exclusion at school and in the workplace

Dalit women, situated at the crossroads of gender and caste, experience especially intense modes of violence and exclusion.

Caste in the Digital and Global Age

The internet and social media have become instruments of caste mobilisation and resistance. Dalit Lives Matter movements have brought attention to caste injustices on a national and international scale.

Concurrently, caste discrimination has entered diaspora communities, elite institutions, and technology corporations. In 2020, there was a history-making lawsuit in California that accused Cisco of caste discrimination, fueling caste debates in international contexts.

Movements for Social Justice

India has seen various caste-based reform movements:

- Bhakti and Sufi Movements countered caste orthodoxy with spiritual egalitarianism.

- Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule laboured in the cause of education and upliftment of lower castes.

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar spearheaded the movement for Dalit rights and motivated a generation towards converting to Buddhism as a denunciation of caste oppression.

- Periyar in Tamil Nadu initiated the Self-Respect Movement, which challenged Brahmanical dominance and advocated for rationalism.

- These movements have conditioned India’s social justice agenda and remain motivating forces behind activism.

Caste and social hierarchy in India are one of the world’s most entrenched and intricate forms of social stratification. Though legally abolished and constitutionally protected, caste still impacts individual, social, economic, and political life within the nation.

India is at a turning point: it promotes technological progress, economic growth, and democratic life on the one hand and grapples with eliminating centuries-long caste divisions that hold back real equality and social justice on the other.

Eradicating caste discrimination requires more than legal frameworks—it demands a cultural transformation. Education, inter-caste interactions, inclusive economic growth, and strong enforcement of anti-discrimination laws are essential steps forward. A truly egalitarian India will only emerge when caste ceases to be a marker of identity and destiny, and becomes a matter of history.