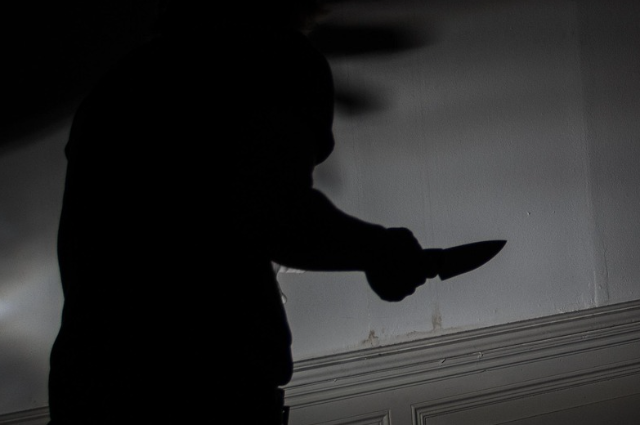

Image by Niek Verlaan from Pixabay

A MURDER IN MADRAS

On the morning of 8 November 1944, C.N. Lakshmikanthan, one of Madras's most notorious and divisive characters, made a routine call on his close friend and legal advisor, J. Nargunam, in the peaceful suburb of Vepery. But what started as a normal day in British India quickly became a story of bloodshed and treachery. As Lakshmikanthan rode a hand-pulled rickshaw home to his residence on Venkatachala Mudali Street in Purasawalkam, a group of unidentified attackers ambushed him. Around 10:00 AM IST, on the busy stretch of General Collins Road, they attacked with surgical precision. One of the attackers stepped forward and stabbed him with a knife before disappearing into the morning crowd.

Wounded but still on his feet, Lakshmikanthan hobbled to a local lawyer's house, where he gasped out the information on the ambush. He was taken to the General Hospital and, as reports tell us, gave a macabre dying declaration. But even medicine and the law couldn't save him. He died of his injuries the next day, leaving not only a dead body but a storm that would engulf the city's upper crust. His killing wasn't just a headline; it was the spark that would set off a scandalous saga of fame, vendetta, courtroom drama, and a justice system strained to its limits. A story that would captivate the nation and go unsolved for generations.

THE MAN WHO LOVED TO HATE

Lakshmikanthan was not a journalist in the classical sense; he was a scandal-monger, a blackmailer disguised as a publisher. In his Tamil journal Cinema Thoothu, and subsequently Hindu Nesan, he pilloried Madras's gaudy film industry. His pages were filled with gossip, half-truths, innuendo, and vicious denunciations of cinema's most popular stars. The distinction between information and extortion became indistinct in Lakshmikanthan's hands. He frequently threatened to reveal sordid secrets and took hush money to keep them unpublished.

By 1944, he had alienated nearly the entire Tamil film industry. Actors, producers, and technicians alike shuddered at the prospect of the next headline bearing his name. Among his victims were two icons of Tamil cinema: M.K. Thyagaraja Bhagavathar, the initial superstar of Tamil cinema, and N.S. Krishnan, a great comedian and social satirist.

THE ATTACK

On the 7th of November, Lakshmikanthan was walking home from a meeting with lawyer Varadachari in Vepery. As his rickshaw reached Brough Road, two assailants accosted him. According to reports from The Indian Express ("C. N. Lakshmikantam Attacked Again", 9 November 1944), the attackers stabbed him several times and fled. Bleeding and weak, Lakshmikanthan managed to reach Varadachari’s home. He was taken to the General Hospital and reportedly gave a dying declaration to the police, describing the attack and identifying at least one of the men.

Even after receiving treatment, he died the following morning. The killing was front-page news immediately. The public and press, already enthralled by Lakshmikanthan's salacious stories, now had a real-life whodunit to speculate on.

A DRAMATIC TURN: CELEBRITY ARRESTS

Within a short while, a list of suspects had emerged and, to everybody's surprise, the list included movie stars M.K. Thyagaraja Bhagavathar and N.S. Krishnan. They were arrested along with the others. The charges were based on the story that they had plotted to kill Lakshmikanthan in revenge for his persistent mudslinging campaigns.

The media hype was unprecedented. According to Randor Guy's 2004 piece "Defender of Lost Causes" (The Hindu), the arrest of such giants of cinema caused public outrage and protest. Bhagavathar, a devout and spiritual vocalist, and Krishnan, famous for his sense of humor and moralistic comments, were now suspects in a horrific murder.

THE TRIAL

The case of the prosecution was circumstantial to a large extent. There were also retracted confessions and contradictory witness statements. The Sessions Court, however, convicted Bhagavathar and Krishnan in 1945 and sentenced them to life imprisonment. Public opinion was divided; while some opined that the law had fulfilled its purpose, others were convinced that the pair had been framed.

Krishnan and Bhagavathar protested their innocence and appealed to the Madras High Court, which confirmed the convictions. But in a precedent-setting judgment in 1947, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London overruled the verdict on grounds of tainted evidence and miscarriage of justice. The appeal memorandum brings out glaring gaps in the prosecution and investigation.

AFTERMATH: STARDOM LOST, LIVES CHANGED

Though acquitted, the harm was done. Bhagavathar, once the golden voice of Tamil cinema, never achieved his former glory. His films were boycotted, producers refused to cast him, and he died in 1959, a shadow of his former self. Krishnan, though stronger, also failed to recover his reputation. He came back to the stage but lived under the cloud of his imprisonment.

The actual murderers were never discovered. The police shut down the case, leaving a maze of unresolved questions.

WHY DID HE HAVE TO DIE?

Who really murdered Lakshmikanthan? Was it a revenge killing by furious celebrities? Or was there a more sinister conspiracy involving players who wished him silenced for good? As observed in The Hindu article "A Hint of Scandal in Madras" by T.A. Narasimhan and B. Kolappan (2014), there were rumors of political links, underworld goons, and even collusion with law enforcers.

Lakshmikanthan's tough reporting had made him a thorn in the sides of not only movie stars, but also of influential individuals who feared being exposed. Some say he was a martyr to freedom of speech; others say he is a cautionary example of the misuse of media power.

A LEG...

The case continues to haunt Chennai. As recently as March 2023, The New Indian Express has indicated that the 79-year-old case of murder was again under scrutiny, fueled by renewed curiosity among legal historians and digital detectives.

The Hindu re-looked at the story in a spookier feature in January 2024, "Lakshmikanthan Case: When a Poison Pen Met with Murder". It went into detail about how a scandal- and publicity-hungry writer got his comeuppance fitting for a noir thriller.

A CASE THAT REFUSES TO DIE

The Lakshmikanthan murder case is not a whodunit. It is a story about India in the 1940s—a country on the brink of independence, where film was emerging as a mass religion, where media influence was unbridled, and where the justice system failed in the spotlight of celebrity and public opinion.

Almost 80 years on, we still don't know who murdered C.N. Lakshmikanthan. But his assassination and the lives destroyed in its wake are a reminder of the perils of fame, revenge, and the deadly cost of writing with a poisoned pen.

. . .

References:

- Frederick, Prince (2013). "Gripped by sleaze, sex and murders."

- The Hindu. Guy, Randor (2004). "Defender of lost causes."

- The Hindu. Muthiah, S. (2003). "The Varadachariar viewpoint."

- The Hindu. Narasimhan, T.A., Kolappan, B. (2014). "A hint of scandal in Madras."

- The Hindu. "C. N. Lakshmikantam Attacked Again."

- The Indian Express, 9 Nov 1944. "C. N. Lakshmikantam Dies in Hospital."

- The Indian Express, 10 Nov 1944. "Transcript of the verdict in M.K. Thiagaraja Bhagavathar And Ors. vs on 29 October 1945". Indian Kanoon.

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai

- https://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/chennai