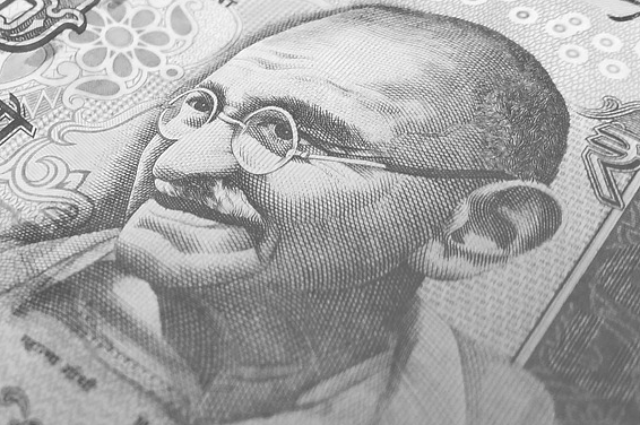

Image by Codes Colors from Pixabay

We, the people of India, are indebted to Mahatma Gandhi for preaching to us the gospel of love, non-violence and satyagraha. Humanitarian values should be given supreme importance above any faith or belief system. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi stood by this principle throughout his life. The charismatic leadership and the astounding ability of Mahatma Gandhi to attract masses irrespective of caste, creed, religion or sex stems from the fact that he had persevered in South Africa, where he spent 21 years of his life, first in developing a flourishing legal practice and later representing and fighting for the Indian diaspora residing there in the face of social discrimination. His role as a Civil Rights champion in South Africa actually prepared the ground for his full-fledged political activism in the colonial Indian scenario. On his return to India from South Africa in 1915 at the age of forty-five, Gandhiji's mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale advised him to travel extensively through the length and breadth of the country to understand and get a first-hand experience of the social fabric, the economic situation of the common people and their trials and tribulations of being citizens of a subjugated nation. Gandhiji followed this advice and gathered as much knowledge as he could by travelling across the country. His foray into the political arena of India is an amazing journey whereby he made a direct impression on the minds of the people with his fiery speech from the podium of Benaras Hindu University in February 1916 (where he was invited to the founding ceremonies), vehemently criticising sycophantic princes of provinces and most obviously the British Raj and its despotic policies. His rebellious attitude disquieted the regime.

Mahatma Gandhi had practised the path of Satyagraha in South Africa and was successful in his experiment. Now, after his return to his motherland, it was time to put to the test his ideal of Satyagraha to 300 million people who were chained in the shackles of foreign domination and were yearning for an able leader who would emancipate them. According to Gandhi, Satyagraha is just a new name for the "law of suffering". It is a relentless search for truth and determination to reach truth without resorting to hatred, violence or rancour. "It is an action oriented search and adherance to truth and a non - violent fight against untruth." Gandhiji was in search of a test case for his tool of Satyagraha on Indian soil and as fate would have it, Satyagraha found him in the form of three pressing issues which were desperately crying for help in three different locations - Champaran in Bihar and Kheda and Ahmedabad in Gujarat. Chronologically, the Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 was the first satyagraha movement led by M.K. Gandhi. The Civil Disobedience Movement at Champaran connected Gandhiji to the masses, and his hard work in liberating thousands of poor peasants made him the Mahatma.

1916 was a landmark year for the Indian National Congress, as there were reconciliatory efforts made by Balgangadhar Tilak, by virtue of his searing persona, on behalf of the Congress and Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the negotiator on behalf of the Muslim League. The result was the signing of the Lucknow Pact, which saw the forging of alliances between not only Congress and Muslim League but also between the Moderate faction and the Extremist faction, which had parted ways in 1907 during the Surat Session. On the sidelines of these important developments taking place, a meeting took place between Gandhiji and Raj Kumar Shukla, a peasant from Champaran. He was present in the Lucknow session to speak on the resolution related to the deplorable condition of the peasants in Bihar's indigo plantations. He first approached Tilak for intervention; however, Tilak thought this issue to be too localised to attach importance. Then, he approached the budding but not yet the leading figure in Indian Politics, M.K. Gandhi, for looking into the matter. At first, Gandhiji was also reluctant, like Tilak and tried to turn down the proposal of visiting Champaran; however, an ever-persistent Shukla tracked him down at every other venue and meeting where Gandhiji went, and with continued pursuit was finally successful in bringing Gandhiji to Champaran. Once he reached Muzaffarpur, the largest town in North Bihar and visited Motihari and Bettiah in the company of Raj Kumar Shukla, J.B. Kriplani and a group of lawyers comprising Rajendra Prasad and Brajkishore Prasad and others, later joining him in his mission, Mahatma Gandhi realised the gravity of the situation which was kept in waiting by the political fraternity of the land. The atrocities of the European planters were appalling. The draconian colonial law of Tinkathia - where a ryot was obliged to cultivate indigo on 3/20th and later 1/10th proportion of their land or else pay an exorbitantly high rent, known as Sharabeshi to the factory - inflicted great misery onto the peasants. Refusal to follow this tinkathia dictate of the European planters called for confiscation of their lands. Needless to say, there existed an unholy nexus between the planters and the British Government, which kept this violation of the civil rights of the sharecroppers going on for a long period. Nevertheless, Gandhi took this opportunity to introduce measures for the alleviation of the misery of the ryots, which were quite novel not only to his own countrymen but also to the British regime, which had a notion that the Indians could not manage their own affairs. Noted historian Ramchandra Guha, in his autobiography on Mahatma Gandhi titled "Gandhi - the years that changed the world, 1914-1948" provides a vivid account of Gandhiji's Champaran expedition. The key aspects of his first unique experiment with Satyagraha on home soil may be outlined in bullet points below.

- Organised Workflow and Planned Execution - Right from patient observation, to exchanging dialogues with the ryots, to sending formal communications to the District authorities and undertaking the legal route, the entire work schedule was duly planned, well organised and wonderfully executed. Gandhiji extensively toured the Champaran district and that too in the presence of Government officials and collected approximately 7000 testimonies of sharecroppers, which means his growing popularity and his methodical passive resistance restricted the British Government from enforcing prohibition on his activities.

- Documentation Approach - Documentation is the key when we deal with important affairs, especially legal affairs, because that helps the case to stand strong by virtue of noting down facts and figures. This approach was shown by Gandhiji in the Champaran case. As already mentioned, grievances of peasants were noted, and the sample size of grievances was quite large, which the British court could not ignore. It is needless to say that all his correspondence to the likes of the indigo planters' association and the Government District Commissioner was drafted to convey his actual intentions without any pretension.

- Grooming of co-workers - Gandhiji took the pain to groom his co-workers in alignment with his method of Satyagraha. He was so far-sighted that he ensured the campaign of passive resistance against the indigo planters and the British government to continue even in his absence, owing to the possibility of his imprisonment for the act of defiance. He prepared a set of rules for his co-workers to follow in case he was arrested, to continue with the investigation into the peasants' grievances under the leadership of Brij Kishore Prasad, a witty lawyer who was also involved in the Champaran case even before Gandhiji arrived at the scene. Also in the initial phase of his campaign, he got acquinted with a group of lawyers who had come to assist him in his cause from Patna; these men had brought their personal servants with them and followed a not - so - disciplined routine. Gandhiji dissuaded them from this practice of indulging in excesses and persuaded the lawyers to live more frugally. His influence was so profound that the lawyers followed suit. This was because Gandhiji preached what he himself practised.

- Engaged in Constructive work - Let us understand the circumstances when Gandhiji reached Champaran. He had his constraints - he was new on the block, although he was well versed with agrarian distress, which he experienced back in South Africa; the political scenario was different in India, and variables changed, and he needed to form new equations afresh. This was his first opportunity. He was also new to the dialect used there. However, a true leader and a ferociously hard worker that he was, these limitations were too small to restrict him from achieving his goal. Moreover, his moral outlook urged his conscience to do more than just interact with the poor, ignorant and illiterate peasants. It became clear to him that these peasants were accustomed to being exploited and living in constant fear. What they needed was to be "free from fear", as he aptly said. Thus, he directed his efforts to uplift them by imbuing in them the importance of hygiene, health and education. Gandhiji took upon himself the task of scavenging, washing and sweeping and opened six schools to impart basic education. His wife, Kasturba, also came to assist her husband in his mission.

- Network Building - It was in Champaran that Gandhiji initiated building a strong network of colleagues who conformed to his ideals of serving the mother nation. These people would later be his political collaborators, assisting him in his future endeavours of India's freedom struggle. A week after he arrived at Champaran, Gandhi wrote in a letter to his old comrade from South Africa, Henry Polak, "I am recalling the best days of South Africa... The people are rendering all assistance. We shall soon find out Naidoos and Sorabjis and Imams. I don't know that we shall stumble upon a Cachalia".

The aforementioned attributes displayed by Gandhiji reflect the qualities of a top-class leader. He stood his ground and, despite a laid-back attitude of the British Government in initiating redressal of the long-standing grievances of the peasants based on facts and there being no room for imagination, he was determined to win his case. He refused to leave the region. Finally, the Government gave in and, recognising the grievances, instituted the Champaran Agrarian Committee with Gandhi as a member. After a series of deliberations of the Committee, the Champaran Agrarian Act was passed on April 26, 1918, which subsequently abolished the notorious "Tinkathia" system. The Government was compelled to return the revenue collected unlawfully.

A simple methodical approach to the problem, coupled with unquestionable dedication to truth, Gandhiji, the karmayogi, emerged triumphant, and with that, the nation got its iconic leader. Comparing Gandhiji's work in Champaran or, for that matter, in any other place at any point of time in his long battle for the freedom of India, we do not find him hurling abuses or rhetoric even in the face of oppressive measures of the British. It was his work that spoke louder than words in contrary to what we see in our politicians today. It's more of blowing one's own trumpet than actually doing good for people. In current times, everyone wants to be a firebrand leader with an inclination to fulfil their personal aspirations by stirring up unrest amongst the common public. There is a growing need for political leaders to pause, reflect and introspect. The lesson drawn from Gandhiji's Champaran Satyagraha applies to people in leadership roles and also to people aspiring to be in a leadership role in any profession. It gives us a model of ethical leadership, non-violent resistance and people-centric government and not to forget, it teaches us a very structured way of working on a project, combining the traits of being meticulous, diligent and truthful to one's duty.

. . .