Why Rumi Still Speaks to the Modern Soul

Jalaluddin Rumi is one of the most widely read and quoted spiritual figures in the world today. His verses circulate across cultures, languages, and religions, offering comfort, inspiration, and a sense of inner depth to millions. Born in the 13th century in the Islamic world, Rumi was not merely a poet of emotions but a jurist, theologian, and mystic whose life and writings were deeply rooted in the Qur’an and Islamic spirituality. Yet, centuries after his death, his words continue to resonate with modern readers who feel spiritually restless in an age dominated by speed, noise, and constant explanation.

In popular culture, Rumi is often reduced to isolated motivational quotes, stripped of their spiritual context and theological depth. These fragments, while beautiful, frequently present him as a vague preacher of universal love, detached from his Islamic worldview and rigorous inner discipline. The authentic Rumi, however, was not inviting casual optimism or sentimental emotion. His poetry emerged from intense spiritual struggle, silence, devotion, and a burning love for the Divine. To understand Rumi truly, one must move beyond quotation and enter the experiential world from which his words arose.

At the heart of Rumi’s vision lies a powerful idea: true love cannot be fully contained by language. This insight is crystallised in his famous line, “Close the door of language and open the window of love.” With this statement, Rumi does not reject language entirely; rather, he challenges its authority over ultimate truth. Language, he suggests, is useful for communication and reasoning, but it becomes a barrier when one tries to grasp divine reality. Love, in contrast, is not something to be explained but something to be lived, felt, and embodied.

This article seeks to explore Rumi’s thought by examining the relationship between spirituality and reason, silence and speech, and knowledge and experience. Drawing from Islamic mysticism, Sufi philosophy, and Qur’anic concepts of the heart and inner certainty, it aims to uncover the deeper meaning behind Rumi’s call to transcend words.

In today’s hyper-verbal, over-analytical world—where opinions are endless, debates are constant, and silence is uncomfortable—Rumi’s message feels especially urgent. He invites the modern soul to pause, listen inwardly, and rediscover a form of knowing that lies beyond arguments and definitions. In doing so, Rumi offers not an escape from reality, but a path toward deeper presence, clarity, and love.

Rumi in Historical and Spiritual Context

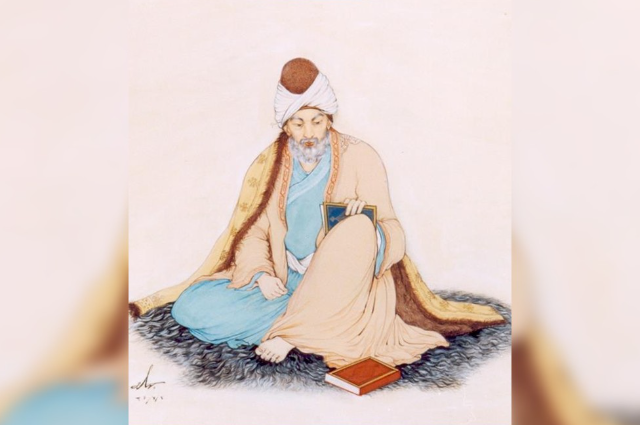

Jalaluddin Muhammad Rumi was born in 1207 in Balkh, a major centre of learning in the Islamic world. From an early age, he was immersed in religious scholarship under the guidance of his father, Baha al-Din Walad, a respected theologian and preacher. When political instability and Mongol invasions forced his family to migrate westward, Rumi was exposed to diverse intellectual and spiritual traditions across the Islamic world, finally settling in Konya, in present-day Turkey. This journey itself shaped Rumi’s worldview, placing him at the crossroads of cultures, schools of thought, and spiritual practices.

Thirteenth-century Anatolia was a vibrant intellectual environment. Madrasas flourished, scholars debated theology, law, philosophy, and mysticism, and Sufi lodges functioned alongside formal institutions of learning. Islamic thought during this period was not divided neatly into “religious” and “spiritual” domains; jurisprudence (fiqh), theology (kalam), philosophy, and mysticism were deeply interconnected. It was within this dynamic milieu that Rumi was educated and later taught. His worldview emerged from a tradition that valued both reason and revelation, discipline and devotion.

Before becoming known as a mystic poet, Rumi was a highly respected jurist and theologian. After his father’s death, he assumed his role as a teacher, delivering sermons, issuing legal opinions, and instructing students in Islamic law and theology. His early writings and recorded lectures reveal a scholar deeply grounded in Qur’anic exegesis, prophetic traditions, and rational argumentation. This phase of Rumi’s life is crucial to understanding him: mysticism did not replace scholarship for Rumi—it deepened it.

The decisive transformation in Rumi’s life came with the arrival of Shams al-Din Tabrizi, a wandering mystic whose intensity and unconventional spirituality shattered Rumi’s structured scholarly world. Shams did not teach Rumi new doctrines; instead, he awakened what lay dormant within him. Their relationship was not merely teacher and student, but a spiritual encounter that dissolved Rumi’s reliance on external authority and redirected him inward. After Shams’s disappearance, Rumi’s grief and longing poured out as poetry, eventually forming the Diwan-e Shams-e Tabrizi. Love became the language of his transformation.

Importantly, Rumi’s spirituality did not emerge in opposition to Islam but from its deepest sources. His poetry is saturated with Qur’anic imagery, prophetic wisdom, and Islamic ethical concepts such as sincerity, humility, trust in God (tawakkul), and purification of the heart. Rumi never abandoned prayer, law, or belief; rather, he sought to uncover their inner meaning. For him, Sufism was not a separate religion but the inner dimension of Islam.

A common misconception presents Rumi as “only a poet” or as a universal mystic detached from religious tradition. This view overlooks the discipline, scholarship, and theological rigor that shaped his spiritual journey. Rumi used poetry not as an artistic escape, but as a necessity—because ordinary language failed to carry the weight of divine experience. Understanding Rumi historically and spiritually reveals him not as a romantic idealist, but as a deeply rooted Islamic thinker whose message continues to challenge and transform hearts across centuries.

Diwan-e-Shams-e-Tabrizi: Poetry as a Spiritual Testimony

The Diwan-e-Shams-e-Tabrizi stands as one of the most intense and unconventional works in the history of spiritual literature. Unlike carefully structured poetic collections composed for aesthetic refinement, this Diwan is a torrent of lived emotion, spiritual ecstasy, longing, and loss. Written largely after the disappearance of Shams Tabrizi, the work is not a systematic treatise but a spontaneous outpouring of Rumi’s inner transformation. It consists primarily of ghazals—short lyrical poems—along with quatrains, composed in moments of spiritual overflow rather than deliberate artistic planning. Its lack of linear structure reflects the nature of mystical experience itself: fluid, eruptive, and resistant to order.

For Rumi, poetry was not an ornament added to spirituality; it was the by-product of spiritual experience. The verses of the Diwan arise from states of haal—temporary but overwhelming spiritual conditions—rather than from intellectual reflection. Rumi did not sit down to “write poetry” in the conventional sense; rather, poetry happened to him. This is why the Diwan often feels urgent, repetitive, and emotionally raw. It captures the immediacy of encounter, not the polish of performance.

Love is the central force of the Diwan, but it is a love layered with meaning. On one level, the poems express Rumi’s deep longing for Shams, whose presence shattered Rumi’s former identity and whose absence created an unhealable wound. On a deeper level, Shams becomes a symbol of the Divine Beloved. Rumi himself dissolves the distinction between the human and the divine, using Shams as a mirror through which divine love is reflected. In this sense, remembering Shams is inseparable from remembering God; personal grief becomes a gateway to metaphysical realisation.

The emotional intensity of the Diwan is heightened through deliberate poetic techniques. Repetition mirrors obsession and longing. Paradox—fire that cools, silence that speaks, loss that becomes union—reflects the contradictions of mystical experience. Symbolism abounds: wine, intoxication, fire, the sun, the ocean, the moth and the flame. These images do not function as metaphors to be decoded once and discarded; they are invitations to enter an altered way of seeing reality.

Yet throughout the Diwan, Rumi repeatedly acknowledges the failure of language. Words strain under the weight of experience. Metaphors collapse. Meanings overflow. Again and again, Rumi gestures toward silence, declaring that what he truly wants to say cannot be said. This tension gives the Diwan its power: it speaks passionately while simultaneously undermining speech itself.

Ultimately, Rumi uses poetry to point beyond poetry. The verses are signposts, not destinations. They are meant to unsettle the reader, ignite longing, and then fall away, leaving the heart alone with the Beloved. In this way, the Diwan-e-Shams-e-Tabrizi functions not as literature alone, but as a living spiritual testimony—one that invites the reader not to admire Rumi’s words, but to undergo their own transformation.

The Limits of Language and the Failure of Words

Language is one of humanity’s greatest tools. Through words, human beings analyse reality, classify experience, preserve knowledge, and communicate ideas across time and space. Logic, philosophy, science, law, and education all depend upon the precision and structure of language. It allows the mind to organise the world, draw distinctions, and construct meaning. Rumi fully acknowledged the necessity of language in ordinary life and religious learning; after all, the Qur’an itself is revealed in words. Yet, for Rumi, language reaches a boundary beyond which it can no longer serve as a reliable guide to spiritual truth.

Spiritual reality, in Rumi’s understanding, is not an object that can be defined, measured, or logically dissected. Divine love, union, and inner awakening are lived experiences rather than concepts. Words function by separating one thing from another, but spiritual experience is essentially unitive. When language attempts to grasp the Infinite, it fragments what is whole. This is why Rumi insists that love must be entered, not explained. Language can describe the path, but it cannot walk it on behalf of the seeker.

Rumi was particularly critical of verbal knowledge that breeds pride. He repeatedly warned against scholars who accumulate words but lack inner transformation. In his view, excessive reliance on speech and argument often strengthens the ego rather than dissolving it. Intellectual mastery can create the illusion of spiritual superiority, trapping a person in concepts while leaving the heart untouched. Rumi’s challenge is radical: knowing about love is not the same as loving; speaking about God is not the same as knowing God. When language becomes an end in itself, it blocks the very truth it claims to convey.

This distinction reveals the difference between information and transformation. Information is transferable; it can be memorised, repeated, and debated. Transformation, however, demands participation. It alters perception, identity, and behaviour. Rumi’s famous metaphor compares spiritual knowledge to tasting sugar: no amount of description can replace direct experience. One may analyse sweetness endlessly, but only tasting reveals its reality. In the same way, divine love is not understood through explanation but through surrender.

Modern psychology and communication studies unintentionally echo Rumi’s insight. Research shows that a large portion of human communication is non-verbal—tone, presence, silence, and emotional resonance often convey more than words themselves. In therapy and contemplative practices, silence is recognised as a powerful space where insight emerges. Over-verbalisation can sometimes distance individuals from authentic feeling, while quiet awareness allows deeper understanding. These modern findings confirm what mystics like Rumi knew intuitively centuries ago.

For Rumi, silence is not ignorance; it is a higher form of knowing. Silence is the state in which the ego loosens its grip, and the heart becomes receptive. It is not the absence of sound, but the presence of attention. In moments of true prayer or deep love, words often fail, leaving only a trembling stillness. Rumi famously declared, “Silence is the language of God; all else is a poor translation.” In this silence, the soul listens rather than speaks, receives rather than argues.

This understanding is embodied in Rumi’s adoption of the pen name “Khamush,” meaning “The Silent One.” The name is deeply symbolic. It does not imply muteness, but humility before the ineffable. By calling himself Khamush, Rumi acknowledged the ultimate inadequacy of his own words. His poetry speaks passionately, yet always points toward the moment when speech must end. Silence, for Rumi, is not the rejection of language, but its fulfilment—where words dissolve, and truth is finally encountered.

Silence as the Language of the Divine

In Islamic spirituality and Sufism, silence is far more than the mere absence of speech; it is a deliberate state of attentiveness and receptivity to the Divine. Sufi masters have consistently emphasised that words, while useful for instruction and reflection, are inherently limited when it comes to capturing the Infinite. True understanding of God’s presence emerges not through continuous discourse, but through deep stillness, where the heart becomes attuned to subtler realities that language cannot convey.

The Qur’an itself encourages tafakkur, or deep contemplation, as a path toward spiritual insight. Verses such as “In the creation of the heavens and the earth, and in the alternation of night and day, there are signs for those of understanding” (3:190) invite believers to reflect on the divine order beyond surface appearances. This reflection is not primarily verbal; it is a form of silent, concentrated awareness that engages the heart and intellect simultaneously. In Sufi practice, such contemplation is often paired with solitude, meditation, and moments of prayer in which words recede, allowing the soul to perceive divine truths directly.

Silence, in this sense, is attentiveness, not emptiness. It is a full, conscious presence in which one listens for the subtle promptings of the soul. In prayer or dhikr (remembrance of God), there are moments when words fail, when the repetition of formulaic phrases no longer satisfies the yearning of the heart. These are the moments when prayer becomes truly wordless, when the soul communicates with the Divine without the mediation of speech. Sufi teachers describe this as a dialogue of the heart—a presence that transcends logic and verbal expression.

The psychology of stillness further explains its transformative power. Silence allows the ego, with its attachments, fears, and incessant mental chatter, to recede. When the mind is not dominated by constant analysis or articulation, the heart is freed to open, to receive subtle experiences of love, awe, and awareness. In this receptive state, spiritual perception becomes more acute: the individual begins to experience unity, compassion, and an expansive sense of being. The internal focus of silence nurtures clarity, equanimity, and emotional depth, creating fertile ground for spiritual insight.

Silence also serves as a purifying force, preparing the heart for divine illumination. By suspending the dominance of the self and the intellect, the practitioner creates a space in which the Divine presence can be felt directly. Rumi’s mystical insight, as captured in his pen name “Khamush” (The Silent One), reflects this principle: he embraced silence not as absence, but as the ultimate language of God. In this sacred quiet, the heart becomes a receptive window, allowing the soul to experience love, guidance, and spiritual union beyond the confines of words.

In essence, silence in Sufi spirituality is both a method and a manifestation of divine communication—a conscious stillness through which the ineffable can be sensed, understood, and lived. It is through this silence that the heart is prepared for the transformative power of divine love.

Ishq: Divine Love Beyond Human Emotion

In the spiritual vocabulary of Islam and Sufism, Ishq occupies a realm far beyond ordinary human emotion. While hubb refers to natural love—affection rooted in desire, attachment, or benefit—Ishq signifies an all-consuming, transformative love that dissolves the boundaries between the lover and the Beloved. Hubb may comfort the heart, but Ishq overturns it. Rumi places Ishq at the very centre of spiritual life, presenting it not as a feeling to be controlled, but as a force that seizes the soul and redirects its entire orientation toward the Divine.

For Rumi, love is not about possession or fulfilment of desire; it is about union. Human love often seeks completion through another, but Ishq seeks disappearance in the Other. In this sense, love is not something the seeker “has”; it is something the seeker becomes. Rumi repeatedly challenges the idea that love is meant to bring pleasure or security. True love, in his vision, shatters comfort, destabilises identity, and pulls the lover out of the familiar self into a vast, unknown reality. What appears as loss is in fact liberation.

This transformative aspect of Ishq is closely tied to the Sufi concept of fana, the annihilation of the ego-self. Fana does not imply physical destruction or nihilism; rather, it is the dissolution of the false sense of separateness that the ego constructs. Through Ishq, the “I” that claims autonomy and control gradually melts away. Rumi describes this process as a necessary death before true life. Only when the self is surrendered can divine presence fully inhabit the heart. Ishq, therefore, is not sentimental—it is demanding, uncompromising, and ultimately purifying.

Because Ishq is an experiential reality, it cannot be fully defined. Definitions rely on boundaries, but Ishq erases boundaries. Rumi uses paradox and metaphor precisely because literal explanation fails. To define Ishq is like trying to cage the wind or weigh fire. One may speak of its effects—intoxication, surrender, burning, union—but Ishq itself remains elusive. This is why Rumi insists that love must be tasted, not discussed. It is known only through immersion.

Among Rumi’s most powerful metaphors are the ocean and the wave. The wave appears to be a separate entity, rising and falling with its own form, yet it is never truly separate from the ocean. In ordinary perception, humans see themselves as individual waves—distinct, temporary, and vulnerable. Ishq reveals that the wave is nothing but the ocean in motion. When the wave recognises its true nature, fear disappears. Death loses its terror because nothing real is lost. This realisation is not intellectual; it is the lived insight of love.

Rumi also presents Ishq as the driving force of the universe. Creation itself, in his vision, unfolds through love. Every movement, attraction, and transformation is powered by the longing of the created for the Creator. Love is the hidden energy that draws planets in their orbits and hearts toward meaning. Without Ishq, existence becomes mechanical and lifeless; with it, even suffering gains purpose.

Ultimately, Ishq removes fear, division, and ego. Fear arises from separation, division from illusion, and ego from false identity. When love consumes the self, there is no “other” left to fear or oppose. Rumi’s Ishq unites rather than divides, dissolves boundaries rather than enforcing them. It transforms religion from a system of rules into a living relationship, and faith from belief into intimacy. In this sense, Ishq is not merely a spiritual concept—it is the very heartbeat of reality itself.

Knowledge Beyond Reason: Ilm al-Yaqeen and Ilm al-Ladunni

Islamic thought recognises that knowledge is not a single, uniform category. While reason and learning are highly valued, revelation and spirituality emphasise that the deepest truths cannot be accessed by intellect alone. The Qur’an repeatedly praises those who reflect, understand, and seek knowledge, yet it also makes clear that guidance ultimately comes from God and is received by a prepared heart. Within this framework, Islamic scholars distinguish between acquired knowledge and inner certainty, a distinction that lies at the core of Rumi’s spiritual philosophy.

Acquired knowledge (‘ilm kasbi) is learned through study, language, and instruction. It includes theology, law, philosophy, science, and ethics. This form of knowledge structures religious life and social order, and Rumi never dismissed its importance. He himself was a master of religious sciences. However, learned knowledge remains external; it informs the mind but does not necessarily transform the being. One may know religious truths and yet remain unchanged inwardly. Rumi warns that when learning becomes a source of pride, it veils the seeker from truth rather than revealing it.

Beyond this lies Ilm al-Yaqeen, often translated as “knowledge of certainty.” This is not mere belief or intellectual assent, but certainty born of experience. The Qur’an uses this term to indicate a level of knowing that arises when truth is personally realised. Ilm al-Yaqeen occurs when knowledge moves from the tongue to the heart. For Rumi, this certainty is achieved through love, surrender, and inner purification. It is the difference between knowing the definition of fire and feeling its heat. Once experienced, such knowledge cannot be undone by doubt or argument.

Even higher is Ilm al-Ladunni, knowledge granted directly by God without intermediary. The Qur’an illustrates this in the narrative of Prophet Musa (Moses) and Khidr. Despite Musa’s status as a prophet and lawgiver, he encounters Khidr, who possesses a divinely bestowed knowledge beyond rational explanation. Khidr’s actions appear illogical and even unjust, yet they are rooted in a wisdom inaccessible to surface reasoning. This story demonstrates that divine knowledge transcends human logic and is bestowed according to divine will, not intellectual effort alone.

Rumi frequently returns to this hierarchy of knowledge to emphasise that truth must be tasted. Explanation can guide, but experience alone transforms. This insight is captured in his famous sugar metaphor: no amount of explanation can convey sweetness to one who has never tasted sugar. In the same way, divine love and certainty cannot be communicated through language alone. They must be lived.

Experiential wisdom, for Rumi, does not negate reason—it fulfils it. Reason prepares the path; love completes the journey. Ilm al-Yaqeen and Ilm al-Ladunni represent stages where knowing becomes being, and understanding becomes illumination. In this knowledge beyond reason, the seeker discovers that truth is not something to possess, but something to enter.

The Heart (Qalb) as the Centre of Spiritual Perception

In Islamic spirituality, the heart (qalb) is far more than a physical organ or a metaphor for emotion; it is the centre of perception, awareness, and moral understanding. The Qur’an repeatedly presents the heart as the faculty through which human beings grasp truth. It is not the eyes that are blind, the Qur’an declares, but the hearts within the chests. This understanding challenges modern assumptions that knowledge is purely intellectual. In the Islamic worldview, reason (‘aql) and heart (qalb) are not opposites, but partners—yet the heart remains the deeper faculty, capable of receiving guidance that reason alone cannot reach.

The Qur’an introduces the ideal of Qalbun Saleem, a “sound” or “whole” heart, as the true measure of spiritual success. On the Day of Judgment, neither wealth nor status will benefit a person, “except one who comes to God with a sound heart.” A sound heart is not one free from emotion, but one purified of arrogance, resentment, hypocrisy, and false attachments. It is a heart that is open, receptive, and oriented toward truth. For Rumi, this inner wholeness is the essential condition for experiencing divine love.

The relationship between heart, love, and guidance is central to both Qur’anic teaching and Rumi’s spirituality. Guidance does not descend into a distracted or hardened heart. Love softens the heart, making it receptive to divine light. Rumi often portrays the heart as a mirror: when clouded by ego and desire, it reflects nothing; when polished through love and humility, it reflects the Divine. Thus, love is not merely an emotion the heart feels—it is the force that prepares the heart to perceive reality as it truly is.

This emphasis on the heart is reinforced by a well-known hadith of the Prophet Muhammad, which states that within the human body is a piece of flesh: if it is sound, the whole body is sound; if it is corrupt, the whole body is corrupt—and that piece is the heart. This teaching highlights that moral and spiritual health originate internally. External actions, rituals, and speech derive their value from the state of the heart that produces them.

Because of this, spiritual transformation must begin within. Rumi repeatedly warns against focusing solely on outward forms while neglecting inner reality. Laws, rituals, and knowledge are meaningful only when they refine the heart. Without inner purification, religious practice risks becoming mechanical or ego-driven. Transformation occurs when love dissolves inner hardness and awakens sincerity.

In Rumi’s vision, love is purification, not sentimentality. Divine love burns away pride, fear, and self-deception. It does not merely comfort the heart; it reshapes it. A purified heart does not cling to illusion or domination—it becomes spacious, humble, and alive. Such a heart perceives truth intuitively and responds to guidance naturally. For Rumi, the journey toward God is ultimately the journey inward, toward a heart made whole by love.

Tawakkul, Ego, and the Death of “I”

At the heart of Rumi’s spiritual vision lies a profound call to tawakkul, complete trust in God. Tawakkul is often misunderstood as passive resignation or withdrawal from effort, but in Islamic spirituality it signifies something far deeper: the surrender of control while remaining fully present and responsible. For Rumi, true trust begins when the illusion of self-sufficiency collapses, and the soul recognises its absolute dependence on the Divine.

Rumi teaches that the greatest obstacle to this trust is the ego, the persistent sense of an independent “I” that seeks control, recognition, and certainty. The ego clings to achievements, knowledge, and identity, believing itself to be the centre of action. Even spiritual practices can become tools of the ego if they reinforce self-importance. Rumi warns that as long as the ego governs the heart, divine love cannot fully enter. Love demands openness, and the ego thrives on separation.

This is why Rumi repeatedly emphasises the death of the self, not in a physical sense, but as an inner transformation. His insight is often captured in the expression, “When I disappear, He appears.” The disappearance of the “I” does not mean annihilation of personality or will; it means the dissolution of false autonomy. What dies is the illusion that the self is the source of meaning and power. What emerges is clarity, humility, and alignment with divine purpose.

Tawakkul, in this light, becomes an act of liberation rather than loss. When the ego loosens its grip, fear diminishes. Anxiety about outcomes fades because the heart rests in trust. Rumi suggests that surrender does not weaken a person; it restores balance by returning agency to its true source. The individual still acts, chooses, and strives, but without the burden of control or the arrogance of ownership.

Spiritual humility, therefore, is not self-negation but freedom. It frees the heart from comparison, competition, and insecurity. In surrendering the ego, one does become nothing; one becomes open to everything that truly matters. For Rumi, tawakkul is the moment when the heart stops insisting and starts listening—and in that listening, divine love finally finds room to dwell.

Rumi’s Message for the Contemporary World

The modern world is saturated with noise—constant information, endless opinions, and relentless argument. Digital platforms reward speed rather than depth, reaction rather than reflection. In such an environment, meaning is often reduced to slogans, and truth becomes something to be defended rather than lived. Rumi’s message speaks powerfully into this condition, not by offering louder answers, but by calling for inner stillness, sincerity, and love as the foundation of understanding.

Many people today experience spiritual exhaustion. Despite unprecedented access to knowledge, self-help resources, and religious content, inner rest remains elusive. This paradox reflects what Rumi identified centuries ago: information does not equal transformation. The mind becomes overloaded while the heart remains undernourished. Rumi reminds us that wisdom cannot be downloaded or debated into existence; it must be cultivated through presence, humility, and lived experience.

One reason modern humans struggle with silence is that silence exposes the self. Without distraction, unresolved fears, doubts, and emptiness surface. Rumi understood this discomfort and saw it as a necessary threshold rather than a problem. Silence is not a void to be escaped but a space in which truth can emerge. In learning to sit quietly—with oneself and with God—the individual begins to hear what constant noise conceals.

Rumi presents love as a healing force capable of restoring unity in a fragmented world. His concept of Ishq dissolves rigid identities and softens hardened boundaries. In a time marked by polarization—religious, political, and cultural—Rumi’s insistence that love erases false divisions feels urgently relevant. Love, in his vision, does not deny difference but transcends hostility. It brings inner peace not by controlling the world, but by reconciling the heart.

Importantly, Rumi’s relevance extends beyond religious boundaries without requiring the removal of his Islamic roots. His universal appeal lies not in detachment from Islam, but in the depth of his spiritual insight, which resonates with the human condition across cultures. Stripping Rumi of his tradition weakens his message; understanding him within it deepens his relevance. His teachings invite dialogue, not dilution.

On a practical level, Rumi’s wisdom encourages simple yet transformative practices: cultivating moments of silence, examining ego-driven reactions, approaching relationships with compassion rather than control, and allowing love to guide intention. These are not abstract ideals but daily disciplines. In choosing stillness over noise and love over argument, Rumi offers the contemporary world not escape, but a way back to meaning, wholeness, and inner peace.

Conclusion: Opening the Window of Love

Rumi’s enduring message can be distilled into a single, transformative insight: truth is not merely to be spoken, but to be lived. Throughout his life and works, Rumi reminds us that language, reason, and knowledge—while essential—are only tools. They point toward reality, but they are not reality itself. When words are mistaken for truth, the heart remains untouched. Rumi’s call is to move beyond explanation and argument into direct experience.

For Rumi, love is the final truth—not a metaphor, not a sentiment, but the very substance of existence. This love cannot be confined to definitions or doctrines. It burns away illusion, dissolves ego, and reveals unity beneath apparent division. Where concepts fail, love succeeds. Where language ends, love begins. It is through Ishq that the seeker encounters the Divine not as an abstract idea, but as an intimate presence.

The heart stands at the centre of this encounter. More than intellect or speech, it is the heart that perceives, recognises, and responds to divine reality. When purified through humility, silence, and surrender, the heart becomes a meeting place—a window through which divine light enters human consciousness. Rumi’s emphasis on the heart is not an escape from reason, but its completion.

To “open the window of love” is to make a deliberate choice: silence over noise, depth over display, transformation over information. It is a commitment to inner work in a world obsessed with outward expression. Rumi does not offer easy answers; he offers a path—one that asks for courage, patience, and trust.

In choosing love over ego and stillness over speech, the modern soul discovers what Rumi knew centuries ago: that the most profound truths are not spoken loudly, but realised quietly, in the depths of a heart made whole by love.

References

- Rumi – Diwan-e-Shams-e-Tabrizi (English Translations & Context)

- The Masnavi of Jalaluddin Rumi – Complete Resource

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī

- The Islamic Roots of Rumi’s Mysticism

- Qur’an – Surah Al-Kahf (Musa and Khidr Narrative)

- Qur’an – Surah Aal-e-Imran (Tafakkur and Creation)

- Qur’an – Surah Ash-Shu‘ara (Qalbun Saleem)

- Hadith on the Heart – Sahih al-Bukhari

- Albert Mehrabian – Communication and Meaning

- Sufism and the Concept of Ishq

- Shams of Tabriz – Life and Spiritual Influence

- Rumi and Silence (Khamush in Sufi Thought)

- Ilm al-Ladunni in Islamic Spirituality

- Rumi in Historical Context (13th Century Anatolia)

- Love, Fana, and Union in Sufi Philosophy