A King Beyond His Time

In an age when most rulers sought to impose their faith by the sword, Emperor Akbar of the Mughal Empire chose a path few dared to walk—one of dialogue, curiosity, and coexistence. Ruling a subcontinent teeming with diverse beliefs—Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Sikhs—Akbar understood that true power lay not in domination, but in harmony.

“Truth is a many-sided crystal, and every faith reflects a fragment of it.” — (Attributed to the spirit of Akbar’s court debates)

Fascinated by different religions, Akbar invited scholars from every faith to the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) in Fatehpur Sikri. These passionate dialogues led him to a bold experiment—Din-i Ilahi, or “Religion of God”—not meant to erase existing faiths, but to blend their best moral teachings into one ethical code of life. It was a personal path to devotion and peace, free from ritual, priesthood, or force.

Din-i Ilahi was Akbar’s spiritual response to a fractured society. In an empire too vast and too varied to be governed by one religious truth, he offered instead a vision of unity—one that tried to transcend religious boundaries and bring hearts together.

Historical Background: The Seeds of Syncretism

When Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar ascended the Mughal throne in 1556 at just thirteen years old, India was a mosaic of cultures, faiths, and languages. His empire stretched across regions where Sunni and Shia Muslims, Hindus of countless sects, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Jews, and Christians coexisted—often uneasily. The dominant political ideology of the time was shaped by Islamic orthodoxy, yet the social fabric was interwoven with indigenous religious traditions and spiritual movements.

Initially guided by regents and orthodox clerics, Akbar gradually asserted independent control, both politically and spiritually. As he matured, he grew increasingly disillusioned with rigid dogmas and sectarian strife, observing how priests and theologians from all faiths often used religion to justify conflict, exclusion, and power. His personal experiences—especially encounters with Hindu Rajput nobles, Jain monks, and Sufi saints—inspired him to seek a deeper, more universal spiritual understanding.

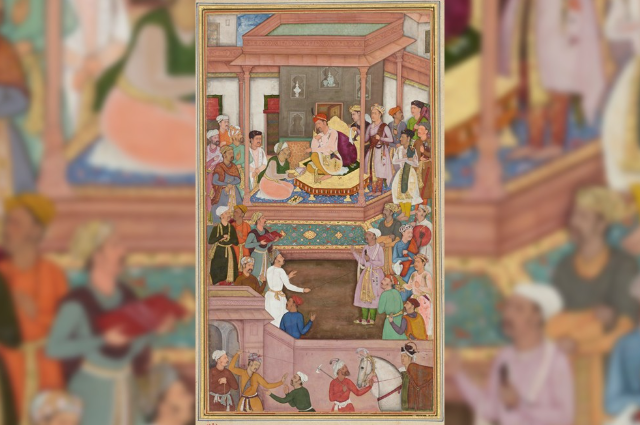

In 1575, Akbar built the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) in his new capital, Fatehpur Sikri. Originally meant for Islamic scholars to debate theology, Akbar soon opened it to Hindu pundits, Jain acharyas, Zoroastrian priests, Christian Jesuits, and even atheists. These intense nightly debates exposed him to a variety of worldviews, often clashing but always enlightening. Akbar asked probing questions, listened carefully, and challenged dogmas—much to the irritation of many traditionalists.

His exposure to Sufism, particularly the Chishti order, encouraged introspection and tolerance. The Bhakti movement (with figures like Kabir and Guru Nanak) emphasised devotion over ritual and unity of God across faiths—ideas that resonated deeply with him. Jain monks like Hiravijay Suri influenced Akbar to adopt non-violence, ban animal slaughter during festivals, and promote vegetarianism. Jesuit missionaries from Goa introduced him to Christian ethics, the life of Jesus, and ideas of charity and forgiveness.

Out of this vibrant, often chaotic, spiritual crucible, the seeds of Din-i Ilahi were sown—not as a dogma, but as a philosophy of synthesis. It reflected Akbar’s growing conviction that no single religion held a monopoly on truth.

Founding of Din-i Ilahi: A Spiritual Experiment

In 1582 CE, after years of interfaith dialogue and personal reflection, Emperor Akbar formally introduced Din-i Ilahi, meaning the “Religion of God.” It was not proclaimed through royal decree or imposed on his subjects, but rather emerged quietly within the court as a deeply personal and spiritual experiment—a reflection of Akbar’s belief that ethical living transcended religious boundaries.

Contrary to common misconceptions, Din-i Ilahi was not a new religion in the traditional sense. It had no sacred texts, no rituals, no temples, and no clergy. Akbar never claimed to be a prophet or divine messenger. His aim was not theological supremacy, but ethical reform. He sought to cultivate a class of individuals—especially among his courtiers—who would live by the highest moral standards, regardless of their religious background.

The core idea was that truth is universal and that every faith holds pieces of divine wisdom. Din-i Ilahi emphasised:

- One God

- Universal brotherhood

- Rejection of religious bigotry

- Devotion through action and morality, not ritual

Akbar personally selected those he believed were capable of embracing this spiritual code—men of integrity, wisdom, and openness, rather than blind followers. Followers were expected to practice celibacy, truthfulness, generosity, and reverence for all life forms. They were also to greet one another with "Allah-u-Akbar" (God is great), symbolising divine remembrance in everyday interaction.

To many, Din-i Ilahi appeared radical, even subversive. But for Akbar, it was not about replacing Islam, Hinduism, or any other faith. Instead, it was about rising above sectarian divisions to create a spiritual fellowship grounded in ethical living and mutual respect.

In essence, Din-i Ilahi was Akbar’s quest for unity in a fragmented world—a visionary attempt to bridge hearts where dogmas had long built walls.

Core Beliefs and Practices

At the heart of Din-i Ilahi was the belief in one universal God—a concept drawn from Islamic monotheism, yet interpreted through a wide spiritual lens. Akbar did not see himself as a prophet or a divine figure, but rather as a spiritual guide—someone tasked with encouraging ethical living and mutual understanding among his diverse subjects.

The central values of Din-i Ilahi revolved around morality, tolerance, non-violence, and universal respect—all drawn from various religious traditions:

- From Islam, it borrowed the idea of Tawhid (oneness of God) and personal devotion, while rejecting the rigidity of clerical dominance.

- The Zoroastrian concept of divine kingship influenced Akbar’s belief that the emperor was chosen by God to uphold justice and righteousness. Fire worship and sun salutations, symbolic of divine light and purity, were integrated into the daily practices of Din-i Ilahi followers.

- Jain philosophy, especially as taught by Acharya Hiravijay Suri, inspired Akbar to promote vegetarianism, ahimsa (non-violence), and compassion toward all living beings. He even banned animal slaughter on certain days across the empire.

- From Christianity, Akbar admired the values of truth, humility, and charity. His discussions with Jesuit priests led him to appreciate the idea of living a life of service, though he rejected exclusive salvation through Christ.

- Sufi mysticism, particularly from the Chishti order, deeply influenced Din-i Ilahi’s spiritual tone. The emphasis on inner purity, God’s love, and detachment from worldly pleasures resonated with Akbar’s quest for spiritual depth.

Instead of rituals, Din-i Ilahi promoted daily ethical conduct:

- Truthfulness in speech

- Generosity toward the poor

- Abstinence from meat and alcohol

- Salutation of fellow believers with “Allah-u-Akbar”, affirming God's greatness in all interactions

- Observance of celibacy, especially for those devoted entirely to spiritual life

Akbar believed that religion should inspire unity, not division. By selectively combining elements from different traditions, he attempted to create a spiritual framework that transcended labels. Din-i Ilahi was thus not a theological system, but a code of ethical monotheism—an invitation to live in truth, peace, and harmony with all.

Followers and Implementation

Despite Akbar’s deep conviction and personal involvement, Din-i Ilahi never gained widespread acceptance. It was not designed as a mass movement, but rather as a spiritual fellowship of select individuals—mostly from within his court—who shared his ideals of moral discipline and interfaith harmony.

Importantly, membership in Din-i Ilahi was entirely voluntary. Akbar never forced anyone to convert, nor did he portray the movement as a replacement for existing religions. He simply invited those he considered open-minded, ethically upright, and intellectually curious to adopt the values of Din-i Ilahi as a personal code of conduct.

Among the few who accepted this invitation were some of Akbar’s closest confidants:

- Birbal, a Hindu courtier known for his wisdom and wit, was the most well-known follower.

- Abul Fazl, Akbar’s chief court historian and author of Akbarnama, also embraced Din-i Ilahi, seeing it as a symbol of Akbar’s enlightened statecraft.

- Faizi, a celebrated poet and scholar, similarly supported the emperor’s vision of spiritual unity.

However, most nobles and courtiers remained cautious. The fear of backlash from powerful religious groups—particularly conservative Sunni Muslim clerics—kept many from associating openly with the movement. Akbar’s attempt to step outside traditional religious lines was considered controversial, even heretical by some.

As a result, Din-i Ilahi remained confined to Akbar’s royal court, more a personal spiritual circle than a structured or institutionalised faith. Yet its symbolic power—an emperor embracing unity over division—resonated far beyond its limited membership.

Criticism and Resistance

While Akbar envisioned Din-i Ilahi as a path to ethical unity, many saw it as a dangerous deviation from religious orthodoxy. Conservative Muslim Ulema were particularly alarmed. For them, Akbar’s questioning of Islamic dogma, his association with non-Muslim scholars, and his claim to spiritual authority signalled a challenge to the very foundations of Islamic belief.

They accused Akbar of heresy (kufr) and blasphemy (shirk)—both serious offences in orthodox Islam. His adaptation of practices from other faiths, like sun worship (from Zoroastrianism) and vegetarianism (from Jainism), was seen as dilution, even mockery, of religious purity. The emperor’s refusal to follow traditional Islamic rituals—such as leading Friday prayers or observing strict fasting—deepened the suspicion.

Beyond the court, clerics and preachers spread fear among the masses, warning that Din-i Ilahi was a political tool to undermine Islam. Pamphlets and oral sermons labelled Akbar an apostate, and stories of his "godless religion" circulated widely. Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, a powerful Islamic reformer, became one of Akbar’s most vocal critics—denouncing Din-i Ilahi as a threat to Islamic values and urging the restoration of Sharia-based governance.

Faced with growing resistance, Akbar walked a careful line. He never outlawed Islam or Hinduism, nor did he dismantle their places of worship or clergy. Instead, he promoted religious freedom—a radical idea for the time—and allowed people to practice their faiths without interference. Din-i Ilahi was promoted only among his trusted circle, not the general population.

This balancing act—encouraging religious innovation while respecting tradition—was perhaps Akbar’s greatest challenge. While he weathered the criticism during his reign, the seeds of opposition would grow stronger after his death, eventually contributing to the decline of his spiritual experiment.

Decline After Akbar’s Death

The fate of Din-i Ilahi was closely tied to Akbar’s vision and authority. After he died in 1605, the movement began to rapidly decline. His successor, Emperor Jahangir, though educated and cultured, showed little interest in continuing his father's religious experiment. Jahangir preferred to maintain political stability by leaning toward more orthodox Islamic policies, thus avoiding the controversies Din-i Ilahi had stirred.

One major reason for its downfall was that Din-i Ilahi lacked a formal structure—no sacred texts, clergy, temples, or institutional backing. It was a philosophy more than a religion, sustained by Akbar’s personal charisma and moral authority. Without his guidance, the movement had no means to grow or survive.

Additionally, the Mughal court saw a resurgence of conservative Islamic influence under subsequent rulers. Reformers like Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi played key roles in reviving orthodox Sunni beliefs and undoing what they considered Akbar’s “un-Islamic” innovations.

By the mid-17th century, Din-i Ilahi had virtually disappeared from public memory. No new followers were initiated, and it was never mentioned again as part of official policy. Yet, even in its quiet death, it left behind ideas that would continue to echo in the corridors of Indian history.

Legacy: Akbar’s Vision and Its Relevance Today

Although Din-i Ilahi failed as a religion, its symbolic legacy is profound and enduring. Akbar’s bold attempt to transcend religious boundaries made him one of the earliest rulers in the world to champion religious tolerance, pluralism, and ethical governance.

In a time when religion was used to justify conquest and exclusion, Akbar’s vision laid the intellectual foundation for secularism in India. He recognised that in a society as diverse as his empire, unity could not be achieved through uniformity, but through mutual respect and coexistence. His court became a prototype for peaceful interfaith dialogue—a concept that remains crucial today.

Modern historians view Akbar not just as a powerful monarch but as a visionary leader ahead of his time. Scholars like Irfan Habib and A.L. Basham describe Din-i Ilahi as a rare moment in pre-modern history when a ruler attempted to rise above religious dogma in pursuit of shared human values.

In today’s India—where religious tensions and interfaith debates continue to shape the national discourse—Akbar’s experiment offers important lessons. Whether it’s interfaith marriages, communal harmony efforts, or peace talks between religious communities, the essence of Din-i Ilahi—tolerance without erasure—remains deeply relevant.

One recent example is the Supreme Court’s support for interfaith marriages and religious freedom, reinforcing that the state must not favour one religion over another, echoing Akbar’s principles. While Din-i Ilahi as a religion vanished, its message lives on in the ideals of modern secular democracy, making Akbar not only a king of his empire but a pioneer of India’s multicultural future.

Faith as a Bridge, Not a Barrier

Din-i Ilahi was never meant to be a dominant religion or a mass movement. It was Akbar’s deeply personal response to the religious divisions that threatened the unity of his empire. Rooted in a belief that all faiths contain elements of truth, Din-i Ilahi aimed to build moral bridges between communities, not erase their differences. Its journey was brief, but its message—of tolerance, ethics, and universal respect—still echoes centuries later.

Akbar’s true achievement wasn’t in founding a new religion, but in challenging the idea that religion must divide. At a time when most rulers clung to orthodoxy for legitimacy, Akbar had the courage to think differently—to listen to opposing voices, welcome debate, and place compassion above creed.

Though Din-i Ilahi faded with his death, its moral and philosophical legacy endures. In a world still struggling with religious conflict and identity politics, Akbar’s experiment invites us to ask: What if faith were used to unite rather than divide?

Could a movement like Din-i Ilahi survive in today’s polarised world? Perhaps not in form—but in spirit, it already does—in every act of kindness that crosses religious lines, in every law that defends pluralism, and in every voice that dares to preach unity in times of division.