Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos on Unsplash

1. Introduction

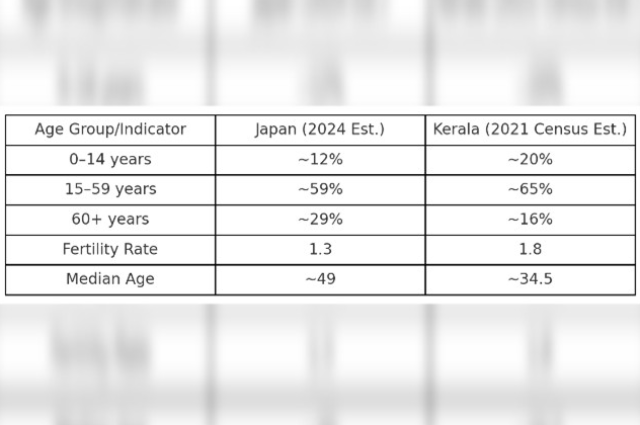

In the quiet suburbs of Tokyo, streets once echoing with the laughter of children now lie silent, lined with empty houses and shuttered schools. Japan, long admired for its technological brilliance and economic prowess, is now grappling with a different kind of challenge—a rapidly ageing and shrinking population. With a median age of nearly 49 and one in three citizens projected to be over 65 by 2036, Japan stands as the world’s oldest major country. The crisis isn’t only about numbers—it’s about vanishing towns, overburdened workers, lonely elderly, and an uncertain future.

But this isn't a uniquely Japanese story anymore. India, despite its reputation as one of the youngest nations, is showing early signs of demographic transition in some regions. Kerala, for instance, has achieved a fertility rate below replacement level (1.8), high life expectancy, and an ageing population—mirroring many traits of Japan’s current situation. As India celebrates its demographic dividend, it must also recognize warning signs that suggest it may not last forever.

This article explores the roots and realities of Japan’s population crisis, using it as a case study for what happens when birth rates plummet, life expectancy rises, and society doesn’t adapt fast enough. But it doesn’t stop there—it draws parallels to India’s evolving demographics, especially in progressive states like Kerala, to examine what the future might hold if timely action isn’t taken. With real-life stories, government responses, expert opinions, and powerful state

2. Historical Background & Current Demographics

Japan’s Rise and Demographic Fall

In the aftermath of World War II, Japan embarked on a remarkable journey of economic reconstruction. The 1950s to 1970s marked the country’s “economic miracle,” accompanied by a surge in population growth due to improved healthcare, industrial development, and higher standards of living. At its peak in the late 20th century, Japan was not only a global economic

However, the very successes that propelled Japan forward would later contribute to its demographic downturn. Increased urbanization, the rising cost of living, intense work culture, and changing family dynamics led to a significant decline in birth rates. By 2005, Japan’s population began to shrink—a trend that continues today. As of 2024:

- The total population is around 123 million, down from 128 million in 2010.

- The fertility rate is just 1.3, far below the replacement rate of 2.1.

- Over 29% of the population is aged 65 or above.

- The median age is nearly 49 years, the highest among major economies.

Japan now has more adult diapers sold annually than baby diapers. It’s not just a statistic—it’s a quiet reflection of a country that is growing old, fast.

Kerala: A Silent Echo of Japan’s Demographic Shift

Thousands of kilometers away, the Indian state of Kerala is displaying a demographic pattern eerily similar to Japan’s—albeit on a smaller scale. Known for its high literacy, advanced healthcare, and progressive social indicators, Kerala has often been considered India’s “model state.” But these very strengths are now contributing to a Japan-like scenario.

- Key parallels include:Fertility Rate: Kerala’s current fertility rate is 1.8, well below India’s national average of 2.0 and below the replacement level.

- Ageing Population: Over 16% of Kerala’s population is above 60, and projections show that by 2036, one in four Keralites could be senior citizens.

- Education & Healthcare: Just like Japan, Kerala’s success in these areas has increased life expectancy and reduced child mortality—creating an aging society without sufficient young replacements.

A major difference, however, is the timeline. Japan’s demographic decline played out over decades. Kerala is still in the early stages, offering a crucial window to learn and adapt.

While India, as a whole, still enjoys a youthful demographic, Kerala is a sneak preview of what may lie ahead for other Indian states as literacy rises and health improves. Just as Japan teaches the world what happens when an ageing crisis is ignored, Kerala offers India a chance to prepare in advance—with awareness, policy, and innovation.

3. Causes Behind the Crisis

Demographic decline is rarely caused by a single factor. In both Japan and Kerala, a complex mix of cultural, economic, and social forces is driving the fall in birth rates and rise in the aging population. Though the two regions differ in history and scale, they now share eerily similar demographic stressors.

Declining Birth Rates: Fewer Children, Smaller Families

In Japan, the fertility rate has plummeted to just 1.3 children per woman, far below the replacement level of 2.1. This isn’t due to a sudden dislike of children, but a shift in societal priorities and pressures. Young Japanese adults cite the rising cost of childcare, intense work schedules, and limited housing as major obstacles.

Yuki, a 34-year-old office worker in Osaka, shared in a NHK interview,

“By the time I finish work, I’m exhausted. I barely have time for myself, let alone think about marriage or kids. Honestly, I’m scared I wouldn’t be a good parent.”

Kerala is beginning to reflect similar concerns. Though India’s national fertility rate remains at 2.0, Kerala’s has dipped to 1.8—a rate that would lead to long-term population decline. Highly educated and urbanized, Keralites increasingly see children as a financial and personal responsibility they’re not ready for.

Anjali, a 28-year-old school teacher from Kochi, said:

“Everyone says Kerala is the best place to raise kids—but even here, the cost of private education, childcare, and career compromise makes me hesitate.”

Ageing Population: Longevity Without Balance

Japan’s ageing is the most advanced in the world, with nearly 30% of its population over 65. This is largely thanks to a robust healthcare system and improved living standards. But as elderly citizens live longer and healthier lives, there are fewer young people to support them, both economically and emotionally.

In a country where social support is traditionally family-based, many older Japanese are left alone. In Tokyo, the term “kodokushi” (lonely death) has become disturbingly common—referring to elderly people dying alone and remaining undiscovered for days or weeks.

Kerala is not far behind. With life expectancy close to 75 years and a growing elderly population (16% and rising), similar concerns are surfacing. The “empty-nest” phenomenon—where elderly parents live alone while children work abroad or in Indian metros—is increasingly visible.

Mr. Balakrishnan, a 71-year-old retired teacher in Palakkad, shared:

“My son is in Dubai, my daughter in Bangalore. They call often, but I cook alone, manage medicines myself, and hope someone helps if I fall ill.”

Work Pressure, Migration & Urban Loneliness

Japan’s corporate culture is infamous for its long working hours, minimal vacation, and emphasis on dedication over personal life. This intense work ethic has created a generation of professionals too exhausted—or too isolated—to prioritize relationships or children.

Tokyo-based psychologist Dr. Keiko Hashimoto explains:

“Work defines identity here. Relationships and family often feel like distractions. That mindset is deep-rooted and hard to change.”

In Kerala, the pattern is different, but the outcome is similar. The state’s economy heavily depends on migration, particularly to Gulf countries. Young men and women leave for jobs abroad, delaying or even abandoning family life back home.

Shibu, a 32-year-old nurse from Thrissur working in Qatar, admits,

“My plan was to work abroad for 5 years and return. But the money is better here. I’m almost 10 years in, unmarried, and my parents are getting old.”

This outmigration, especially of working-age individuals, leaves Kerala with a growing elderly population but fewer caregivers and local earners. Even within the state, migration from villages to cities has weakened traditional joint family structures that once cared for elders and supported child-rearing.

Cultural & Social Shifts: New Priorities

Both societies are witnessing value changes. In Japan, the ideal of a nuclear family is fading. More people are choosing to stay single, and in some cases, live entirely alone. Concepts like “parasite singles” (young adults living with parents but not forming families) reflect deeper social change.

In Kerala, higher female education, urban aspirations, and career opportunities have changed marriage dynamics. Many women now seek partners who respect their ambitions—and aren’t willing to settle. This delay, often into the 30s, naturally reduces childbearing years.

Two Regions, One Warning

Despite cultural differences, both Japan and Kerala showcase a world where development outpaces adaptation. Better healthcare, higher education, and job opportunities were supposed to enhance quality of life—but without supportive family policies or social frameworks, they’ve led to personal and demographic imbalances.

The declining birth rates and rising elderly population in these two regions are not isolated problems. They are cautionary tales of how progress, if not balanced with family support, mental well-being, and inclusive policies, can quietly create long-term crises.

4. Economic and Social Impacts

Demographic changes are not just about numbers—they shape economies, families, and futures. In both Japan and Kerala, the consequences of a declining birth rate and an aging population are now rippling through society in profound ways. From shrinking labor forces to abandoned villages and strained social systems, the demographic crisis has both visible scars and invisible costs.

Japan: A Shrinking Workforce and Overburdened Youth

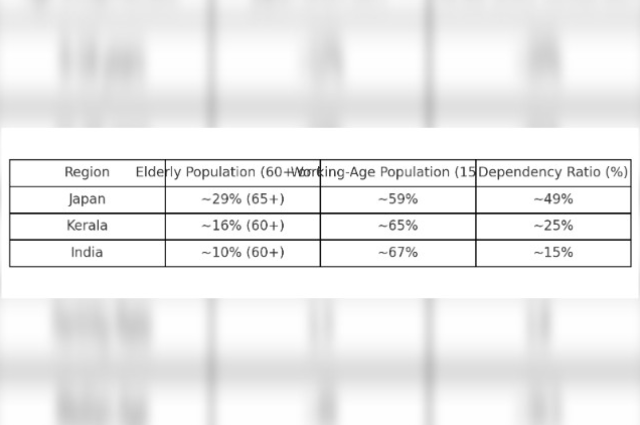

Japan's most immediate economic challenge is its shrinking workforce. With nearly 30% of the population aged 65 and older, the pool of working-age citizens (15–64) is rapidly shrinking. This has led to severe labor shortages, especially in sectors like agriculture, nursing, and manufacturing. Automation and robotics have attempted to bridge the gap, but not without limitations.

Businesses across Japan are feeling the strain. In 2023, a Tokyo-based logistics company had to shut down several delivery routes—not due to lack of demand, but because there were no drivers available.

Meanwhile, the burden on young people is growing. Fewer workers must support more retirees through pensions, taxes, and caregiving. This is not just financial—it’s emotional. Many young adults, already navigating job insecurity and high living costs, are now also responsible for aging parents or grandparents.

Yusuke, a 29-year-old software engineer in Kyoto, shared:

“I work overtime, pay taxes, and send money home for my mother’s care. I want to start my own family, but it feels impossible.”

Ghost Towns, Empty Schools, and Vanishing Villages

Japan’s countryside is filled with "akiya"—abandoned homes—and entire towns where schools and shops have closed. Between 1990 and 2020, Japan lost nearly 9,000 elementary and middle schools due to falling enrollment.

In some towns, local governments are offering abandoned houses for free or token prices to attract young families. But the deeper issue is not just real estate—it's the loss of community, economy, and intergenerational support.

Kerala and India: A Mirror Image in Slow Motion

India is still a young country, with over 65% of its population below 35, but states like Kerala are already showing Japan-like symptoms—especially when it comes to social and economic strain.

Educated but Unemployed: Kerala’s Youth Crisis

With its high literacy rate and large pool of graduates, Kerala faces a paradox: educated youth unemployment. Many young Keralites are unable to find jobs matching their skills, pushing them to seek opportunities abroad. While this brings in remittances, it also drains the local labor pool, leaving behind an aging population with fewer caregivers.

The Care Burden on Fewer Children

As family sizes shrink, the responsibility of caring for elderly parents falls on one or two children—sometimes just one, living abroad. Unlike Japan, Kerala still relies heavily on family-based elder care, but the social structure is weakening. Nursing homes are increasing, but many elderly still face loneliness and lack of daily support.

Meera, a 35-year-old techie in Bengaluru whose parents live alone in Alappuzha, shared:

“I visit them when I can, but it’s hard with work and kids. I worry constantly about their health, but I can't move back either.”

Urban Migration and the Aging of Villages

Internal migration is also accelerating the issue. Young people from villages are moving to Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, or out of state altogether. As in Japan, this leaves many rural areas aged and hollowed out, with fewer farmers, teachers, or local workers.

The state of Wayanad, for example, has seen a consistent outflow of youth, leading to declining school enrollments and shuttered local businesses. Villages, once vibrant, are turning into gray zones—not by design, but by demographic destiny.

Dependency Ratio = (Elderly ÷ Working-age population) × 100

While Kerala’s dependency ratio is still manageable, it is rising steadily—and Japan offers a cautionary tale of what happens when preparation is too late.

The Warning in the Mirror

The economic and social impacts of a shifting population are not future threats—they are present realities. Japan, a pioneer of progress, now faces the challenge of maintaining prosperity with a dwindling base. Kerala, known for its development model, must now balance progress with sustainability, ensuring that its people—young and old—are supported by more than just numbers.

5. Government Policies & Solutions

As demographic stress deepens, governments must adapt with bold, creative, and sometimes controversial strategies. Japan, facing the world’s most advanced population crisis, has experimented with everything from robot caregivers to financial incentives. India, while younger demographically, is already grappling with pockets of aging, particularly in Kerala, and must act preemptively.

🇯🇵 Japan: Fighting Demographic Decline with Innovation and Immigration

Japan has launched a multi-pronged policy effort to slow or reverse its population crisis, focusing on:

Cash Incentives & Child Support

- Local governments offer cash bonuses for each child born—up to ¥1 million (approx. ₹5.5 lakh) in some towns.

- Free or subsidized childcare, education, and healthcare is provided to encourage larger families.

- Yet many say the financial support isn’t enough to offset social pressures or career sacrifices.

Technology & Robot Caregivers

- Japan is a global leader in elderly care robotics.

- In care homes, robots like Pepper and Paro (a therapeutic robot seal) help monitor health, provide companionship, and reduce strain on human caregivers.

- AI-powered toilets and exoskeletons for nurses are part of Japan’s attempt to maintain eldercare amid staff shortages.

Immigration (Reluctantly) Increasing

- Once strict on immigration, Japan is slowly opening doors to foreign workers, especially in sectors like agriculture and caregiving.

- New visa categories and language support have been introduced to bring in caregivers from countries like Vietnam and the Philippines.

- Still, cultural and linguistic barriers remain a major obstacle to long-term integration.

India & Kerala: Caught Between Control and Adaptation

India has long focused on population control, but Kerala is already showing signs that the conversation needs to shift toward population balance and aging support.

Kerala’s Healthcare Model

Kerala is often hailed for its strong public health infrastructure, which has helped increase life expectancy and reduce infant mortality. Now, the focus is turning to geriatric care:

- Primary Health Centers (PHCs) are being upgraded with elder care services.

- Mobile health units and home visit programs are being piloted to reach elderly citizens in rural areas.

Reverse Migration & Employment Schemes

Recognizing the economic and emotional cost of outmigration, Kerala has initiated “reverse migration” schemes:

- The Department of Non-Resident Keralites Affairs (NORKA) offers support for returnees—skill development, job placement, and small business funding.

- Start-up grants and cooperative projects aim to attract young Keralites back home from the Gulf and metros.

Pro-Family Incentives (Emerging)

While India still hosts debates over population control bills, some states are quietly experimenting with pro-natalist policies:

- Kerala has piloted childbirth incentives in districts with declining fertility.

- Some local bodies provide tax breaks or welfare priority to families with more than one child—though these are still in the early stages.

Real-Life Story: Local Schemes in Action

Babu and Radha, a retired couple from Thrissur, live alone since their children migrated abroad. They now benefit from Kerala’s “Vayomithram” scheme, which offers:

- Monthly health check-ups through a local PHC team,

- Emergency helpline services,

- A dedicated care worker who visits once a week.

“It’s not the same as having our children nearby,” says Radha, “but the nurse who visits is like family now. We feel less alone.”

Such initiatives show how state support can soften the impact of social change—but scaling them to reach every aging citizen remains a challenge.

Policy Lessons from Two Corners of Asia

Both Japan and Kerala show that while governments can’t force people to have children or stay close to home, they can:

- Build systems that reduce the cost of caregiving,

- Offer social recognition and support to families,

- Embrace technological and immigration solutions, and

- Plan proactively, not reactively.

Policies must be flexible, empathetic, and long-term—because demographic shifts aren’t solved in a year. They’re managed over generations.

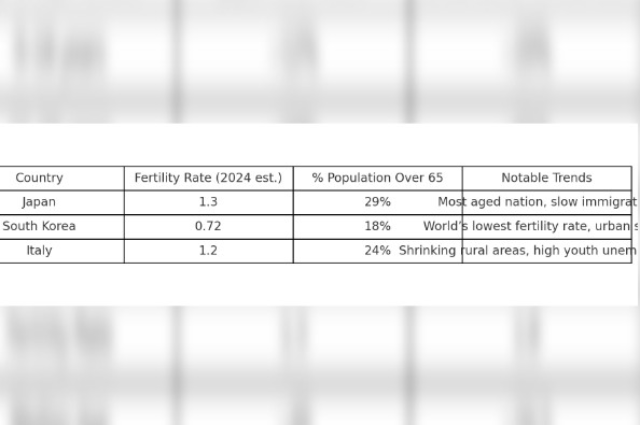

6. Global & Regional Comparison

Population aging is no longer a uniquely Japanese issue. Several developed countries now face similar or even more alarming trends. Meanwhile, in India, the demographic picture is starkly uneven—some states mirror Japan, while others still grapple with overpopulation. These contrasts reveal how aging is both a global trend and a local challenge, requiring region-specific responses.

Japan and Other Aging Countries: A Growing Club

While Japan was the first to feel the full force of population aging, it is no longer alone. Countries like South Korea and Italy are now aging faster than Japan once did.

- South Korea’s fertility rate, now below 0.8, is the lowest in the world. Cities like Seoul are increasingly unaffordable for young families.

- Italy, much like Japan, faces rural depopulation, "ghost villages," and rising pension burdens, despite being in the heart of Europe.

Japan remains the warning bell, but many nations are on the same track—and few have figured out how to reverse it.

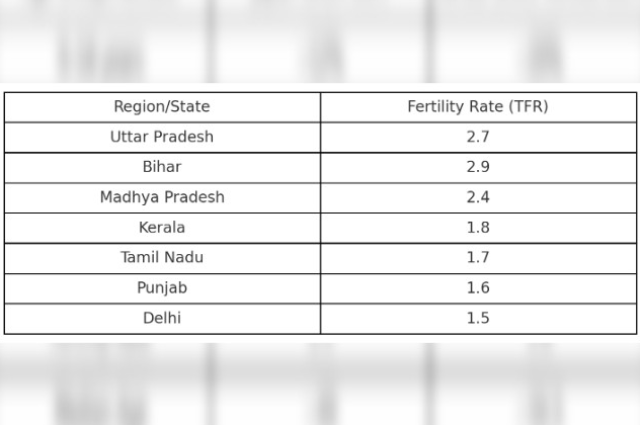

India’s Regional Demographic Divide

- India’s overall population is still growing, but it hides deep regional imbalances:Uttar Pradesh (UP) continues to grow rapidly with a fertility rate of ~2.7, contributing a large share to India's population growth.

- Kerala, on the other hand, has a fertility rate of ~1.8, below replacement level, with signs of aging emerging rapidly.

- Southern states like Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka are also experiencing fertility drops and migration-driven workforce gaps.

Map: Fertility Rate Across Indian States (Latest NFHS-5 Data)

While an actual map can’t be rendered here, here’s a brief overview:

- This creates a North-South divide: The North struggles with resource strain, education, and healthcare due to growing youth populations.

- The South faces challenges similar to aging countries—elderly care, reverse migration, and economic slowdown due to fewer working-age individuals.

India must balance policies, focusing on family planning in the North while preparing for elder care and population stabilization in the South. Japan’s story offers valuable lessons on what happens when aging is ignored until it becomes irreversible.

7. The People’s Voice: What Do the Japanese Think?

Statistics tell one part of Japan’s population crisis, but to understand its emotional reality, we must listen to the voices of the people living it. Across age groups, there is both resignation and reflection—a society aware of its demographic decline, but unsure how to change course.

Why Young Japanese Avoid Parenting

- In a 2023 NHK survey of people aged 18–34, over 65% of women and 50% of men said they had no immediate plans to marry or have children. The reasons are varied—but the most common are:Work pressure and long hours (mentioned by 72%)

- Cost of raising children in cities

- Lack of support for working mothers

- Loss of trust in traditional marriage roles

“I want a child someday,” says Airi, 26, a nurse in Tokyo.

“But I live in a 1-room apartment, my shift rotates every week, and daycare costs half my salary. When would I even see my child?”

“Dating itself is expensive and tiring,” adds Daichi, 28, a systems engineer.“We’re not against love or family—we’re just tired."

In Tokyo’s crowded trains, young professionals often wear earbuds and avoid eye contact—not out of rudeness, but emotional exhaustion. The family ideal has faded into something more distant: a luxury or even a burden.

Elderly Perspectives: Aging Alone, Gracefully or Silently

At the other end of the spectrum, the elderly are coming to terms with loneliness and fragility.

“We raised children, but they moved away,” says Haruko, 74, living in Osaka.

“We Skype sometimes. But mostly, I have my cat and the TV.”

A 2022 study by the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology revealed that over 6 million elderly people live alone in Japan, and nearly 30% feel socially isolated.

Still, many elders accept this fate with dignity:

“This is the Japanese way. We do not want to be a burden,” said Mr. Nakamura, 82, a retired train operator.

“But it would be nice to have someone to talk to every day.”

A Generational Contrast: Values in Transition

Generation: Age 70+- View on Marriage & Family: Essential, duty-drive

- Life Priority: Community, legacy

- Feeling About Japan’s Future: “Declining, but we must adapt."

- View on Marriage & Family: Optional, career-limited

- Life Priority: Self-care, stability

- Feeling About Japan’s Future: “Uncertain and expensive.”

Many older citizens still believe in the post-war ideals of sacrifice and nation-building. Younger ones, however, grew up in a world of stagnant wages and individualism—where marriage and parenting feel more like pressure than joy.

In Their Own Words: A Snapshot

“Family is beautiful. But so is freedom.” — Kana, 23, freelance illustrator

“I worry about dying alone, but not enough to remarry.” — Eiko, 71, widow

“I’d rather care for my parents than have a child of my own.” — Riku, 30, only son

What do These Voices Reveal?

Japan’s people are not unaware—they’re simply stuck between economic limits, cultural shifts, and personal fatigue. The government may offer cash and robots, but healing the emotional and generational gaps is a different kind of policy challenge—one that requires not just plans, but empathy.

8. Future Scenarios: What Lies Ahead for Japan?

Japan stands at a pivotal crossroads. The choices made today—by individuals, communities, and governments—will shape whether the nation thrives in adaptation or declines under the weight of demographic inertia. Let’s explore what the future may hold.

If Nothing Changes: The Slow Fade

- If fertility remains low, immigration is restricted, and elderly support under-resourced, Japan could face a gradual national shrinkage: The population will drop from 123 million (2024) to around 87 million by 2050, and possibly 50 million by 2100, according to Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

- Nearly 40% of the population will be over 65 by mid-century.

- Rural areas will see further “genkai shūraku” (villages on the brink of extinction).

- The tax base will shrink, pressuring healthcare, pensions, and public infrastructure.

- Social isolation among seniors may become a public health crisis.

“We risk becoming a country of caretakers with no one left to care for,” warned a 2022 white paper by Japan’s Cabinet Office.

With Smart Reforms: A New Path Forward

- If Japan expands reforms successfully, several positive transformations are possible:Revival of rural areas through incentives for families, telework zones, and green living hubs.

- New jobs from caregiving, AI, and eldertech, tailored to an aging but still active population.

- Expansion of AI-driven services, such as robotic home aides and smart cities, will ease labor shortages.

- Controlled immigration with cultural integration support could strengthen the workforce and bring diversity.

- Promotion of multigenerational housing, encouraging community support and reducing isolation.

The Role of Technology and Immigration

- Automation may replace some labor gaps—robots in agriculture, transport, and elderly care are already proving useful.

- AI-powered decision-making could optimize urban planning, elder monitoring, and service delivery.

- However, human care still matters—and that’s where targeted immigration policies can help.

- Countries like Canada and Germany show that well-managed migration can rejuvenate economies without cultural collapse

Japan’s Population Projection

2024:

- Status Quo (Low Fertility, Low Immigration): 123 million

- Optimistic Reform Scenario: 123 million

2050:

- Status Quo: 87 million

- Optimistic Reform Scenario: 98 million

2100:

- Status Quo: ~50 million

- Optimistic Reform Scenario: ~70 million

Source: NIPSSR, Japan Cabinet Office projections

What India Can Learn

India—especially aging regions like Kerala—should watch these outcomes closely. Demographic change is not doom if met with innovation, inclusion, and forward planning. Japan’s story is both a warning and a workbook for the world’s future.

Conclusion: A Shared Future, A Chance to Act

Japan’s population crisis is often portrayed as a distant warning—a singular path shaped by unique cultural and economic factors. But in truth, Japan is not alone. Across the globe, and within India itself, especially in states like Kerala, similar patterns are emerging: declining fertility, rising eldercare burdens, and young people hesitating to start families.

What Japan experiences today could become India’s tomorrow if we don’t act with foresight. But it also offers a chance: to learn from Japan’s missteps and innovations, to invest in families, and to build communities where life—from birth to old age—is valued and supported.

In a quiet town near Kyoto, 31-year-old Keiko and her husband Takeshi recently welcomed their second child.They live in a revitalized rural area where the government provides free daycare, flexible work-from-home setups, and community elder support.“We thought it was impossible,” Keiko said, rocking her baby girl.“But we found help, and now we’re helping others.”

Likewise, in Kerala’s Palakkad district, Anjali and Rahul, both teachers, are raising a son while caring for Rahul’s aging father, supported by a local cooperative that provides home health services.

Their stories are proof that with the right environment, hope can grow—even in aging lands.

Japan vs Kerala: Demographics (Historical Background & Current Data)

- Post-WWII demographic trends in Japan.

- Kerala’s demographic transition over the last few decades.

- Key comparison metrics: Fertility rate, life expectancy, median age.

- Chart: Japan vs Kerala population pyramids.

- Shared characteristics: high literacy, good healthcare, aging society.

Causes of Population Decline

- Japan: low fertility, delayed marriage, urban work stress.

- Kerala: migration, education-driven family planning, career-first youth.

- Real-life inputs: interviews with young people from Tokyo and Kochi.

- Cultural pressures and gender roles.

- Work-life balance struggles.

. . .

References:

- https://www.ipss.go.jp

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/05

- https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h02015/

- https://earth.org/understanding-japans-demographic

- https://www.ipss.go.jp/pp

- https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey

- https://iasp.ac.in/uploads/journal/4.%20Infertility

- https://www.indiabudget.gov.in

- https://earth.org/understanding-japans-demographic

- https://iasp.ac.in/uploads/journal