In an age where human interests dominate ethical and legal frameworks, it is crucial to revisit spiritual and philosophical teachings that promote a broader, more inclusive moral consciousness. It's pretty easy to go through life believing humans are the center of everything. In all this, we tend to forget to ask ourselves unsettling questions about how we treat other living beings, especially animals. Even humans would be alarmed by the sobering reality shown by the answers to these basic questions.

A Gen Z kid might have little to relate with Vivekananda, but the depth of his ideas forces each one of us to come to terms with him, particularly the Neo-Vedantic worldview which is grounded in the oneness of all existence. It offers a compelling alternative to speciesism, the belief in a particular species’ superiority over others. Remarkably, this vision is in resonance with that of contemporary thinkers such as Tom Regan and Peter Singer. Though coming from contrasting and distinct backgrounds—one a monk from 19th-century India and the others modern Western philosophers—they all challenge the moral boundaries that separate humans from animals, urging us to expand our circle of compassion: an idea that Article 51A (g) of the Constitution also emphasizes.

The Oneness

Vivekananda’s philosophy, rooted in Advaita Vedanta, posits that everything in this universe, ranging from a grain of sand to huge skyscrapers, is a manifestation of Brahman. For him, Sachidanand pervades the entire cosmos. “It is the same soul that is manifesting in every being. There is only one throughout the universe,” he affirmed. If we share this one, universal soul with other sentient beings, then why doesn’t an ant deserve as much respect as a human does? Swami gives a clear ethical message: don’t harm any being, because in doing so, you’re harming yourself.

From Vivekananda’s metaphysical understanding arises a radical ethical vision. The value of a being must not be decided by its utility to humans, its intelligence, or social status. Rather, the value stems from the very fact that each being carries the same divine presence. This perspective collapses the moral hierarchies that dominate human thinking and makes way for the acceptance of all beings, including animals, as ‘equals’. Swami didn’t talk directly about animal rights in the way we understand them, but the logic of his philosophy leads us right there.

The Modern Critique of Speciesism

The term ‘speciesism’, first coined by Richard Ryder and popularized by Peter Singer, refers to the arbitrary and unjust idea of treating beings differently just because of their species. It's like believing that humans matter more than cows or pigs, which is as unfair and whimsical as racism or sexism. Singer, in his book Animal Liberation Now, argues that the only thing that should matter while we are making moral decisions is not intelligence or language, but whether a being can suffer. And since animals can suffer clearly, their pain and pleasure matter as much as ours. As Bentham writes, “The question is not, Can they reason?, nor, Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?”

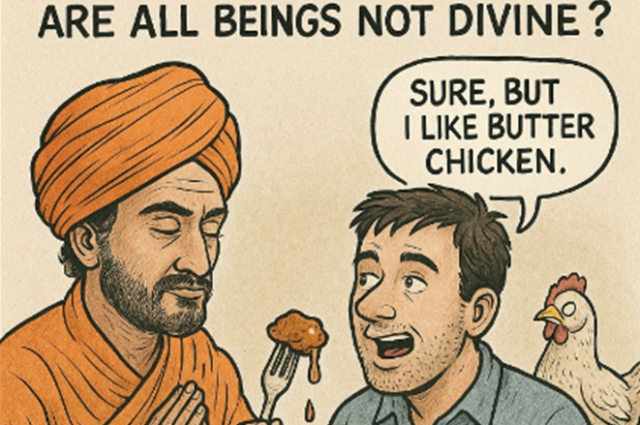

Singer’s approach is rooted in utilitarianism, the belief that we should aim to maximize happiness and reduce suffering for the greatest number of beings. However, in practice, we have conveniently narrowed that circle to include only humans. This selective application gives us, human beings, the right to enjoy dishes like butter chicken every day, guilt-free—except on Tuesdays and Thursdays in Indian households—while ignoring the profound pain and suffering endured by thousands of hens raised in brutal farming conditions.

Tom Regan’s Rights-Based Argument

Regan, in his seminal work The Case for Animal Rights, complements Singer’s argument by offering a deontological perspective. He advocates for the total elimination of commercial animal agriculture, using animals for scientific purposes, and sports hunting. He argues that the fundamental wrong in the system is that it allows us to view animals as our resources, which can be eaten, surgically manipulated, or exploited for sports or money. In contrast, he asserts that animals are “subjects of a life,” individuals with beliefs, desires, memory, and a sense of pain and pleasure. And because they, like humans, have intrinsic value, they have rights that should not be violated.

Regan also criticizes utilitarianism for its potential to sacrifice individual beings for the so-called ‘greater good’ and instead insists on the inherent dignity of each animal. Animals should not be treated as a means to an end but as ends in themselves.

What is fascinating is how all this ties back to Vivekananda’s ideas, even though he didn’t use fancy words like “rights” or “speciesism.” They converge on a key insight: the arbitrary division between human and non-human is morally indefensible. Vivekananda’s assertion that all beings are manifestations of the same Atma mirrors Singer’s and Regan’s insistence on moral equality based on sentience or subjectivity.

Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind provides a valuable historical lens that complements this discussion. Harari argues that human supremacy over animals is not natural or inevitable but rather a product of myths created over time to justify their dominance over animals. He explains how the agricultural revolution led to the large-scale domestication and exploitation of animals, reducing them to tools of labor and food production.

He writes, “The fate of industrially farmed animals is one of the most pressing ethical questions of our time.” This aligns with both Vivekananda’s moral call to Ahimsa, or non-violence, and the ethical outrage expressed by Regan and Singer, underscoring the collective delusion human beings are living in—i.e. WE, THE HUMANS, ARE SUPERIOR.

It Doesn’t End With Us!

AR6 repeated like a mantra the need for plant-based living, and from Greta Thunberg to some unknown, peculiar guy in western Bihar, youth across the world are advocating for veganism. Sure, some random dude will like the Instagram reel mocking how an attention-seeking influencer is eating twice the meat to ensure the vegan next door has no impact at all, but real-world data suggests that the animal activists are creating noise. In India and abroad, animal welfare law is being increasingly taught at elite universities, and the country now has an Ahimsa Fellowship. But amidst this call for action for a much-needed cause, I am reminded of something gloomy that Yuval jokes about: in driving species after species to extinction due to sheer anthropocentrism, or factory farming–-led zoonotic pathogens, humanity may annihilate itself. And perhaps 65 million years from now, intelligent rats will look back gratefully on the decimation wrought by humankind, just as we today can thank that dinosaur-busting asteroid. We must stop at once and ask ourselves: What if it doesn’t end with us?

References

1. Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper, 2015.

2. Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights. University of California Press, 1983.

3. Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation. HarperCollins, 1975.

4. Vivekananda, Swami. The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Advaita Ashrama, various vols.

5. Ryder, Richard D. Speciesism. Centaur Press, 1989.

6. Radhakrishnan, S. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Harper Torchbooks, 1953.