Written with a conscience, for the unheard and inspired by the resilience of Jharkhand’s Adivasi communities and how uranium mining in Jharkhand devastates communities and nature. The circular economy promises to fall short in tackling this crisis. This article exposes the urgent need for real change.

“We were promised electricity and development. Instead, we got sickness and silence.”

— A tribal resident of Jaduguda, Jharkhand.

Rakesh is being carried by his mother for a bath in Bango village. The roughly 18-year-old is confined to his wheelchair due to a physical disability. Photo credit: Subhrajit Sen.

“In the earth’s silent heart, we dig for light,

Circular Economy and Mining: A Complex Relationship

In a world striving to close loops and minimize waste, the circular economy presents a hopeful alternative to our planet's linear, take-make-dispose model. It aims to redesign systems so that nothing is wasted—materials are reused, repaired, and regenerated.

But what happens when the very foundation of that circular model rests on non-renewable, extractive industries like uranium mining? What happens when those most affected by these processes are indigenous communities with no say in the matter? We must mine to grow. But can we grow sustainably?

India, with its expanding energy needs, seeks sustainability. Yet, it continues to rely on linear extraction practices—particularly in resource-rich states like Jharkhand, home to the country’s oldest uranium mines.

This is a story not just about radioactive material but about radioactive silence—a silence endured by the Santhal, Ho, and Munda tribes whose lands now pulse with invisible danger.

Why Mining Still Matters: The Case of Jaduguda

India is one of the top ten mineral-producing nations in the world. Mining contributes around 2.5% to the national GDP, and uranium, though a small piece of this pie, is essential to the country’s nuclear energy program.

Jaduguda, a village tucked in Jharkhand’s East Singhbhum district, became India’s first uranium mining site in 1967, operated by Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL). Today, over 1,000 tonnes of uranium ore are extracted annually, feeding nuclear reactors that light up cities.

But the villages that surround these glowing ambitions remain in the dark—not metaphorically, but literally. Most households near Jaduguda lack basic infrastructure. The only thing they seem to have in abundance is radiation.

The Hidden Fallout: Indigenous Lives on the Frontlines

The shiny promise of development has come at a steep cost — one paid largely by the indigenous Santhal and Ho tribes, whose ancestral lands and lives have become collateral damage.

When you step into Chatikocha, Dungridih, or Bhatin, you will hear stories that don’t make it into annual reports or corporate statements. Stories of loss, mutation, illness, and unanswered questions.

The Case of Gangi Devi: Mother of a Generation Forgotten

Gangi Devi, a 55-year-old Santhal woman, has lived in Chatikocha her entire life. Of her four children, two were born with visible deformities. One died before reaching his teens.

"When I asked the doctor why, he said it’s in our blood. But we never had this before the mines. Our ancestors lived long. My son died at 13."

Her story isn’t isolated. In 2008, a study by Indian Doctors for Peace and Development (IDPD) found that over 30% of children in the Jaduguda region exhibited symptoms of genetic deformities. The same study revealed rising cases of cancer, miscarriages, stillbirths, and infertility—all of which are consistent with chronic low-level radiation exposure.

Despite these findings, no comprehensive government health audit has been conducted. The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) and UCIL have continued to assert that radiation levels are "within permissible limits."

But how do we define "permissible" when lives are visibly altered?

Broken Promises and Unequal Gains

When UCIL arrived in the 1960s, it promised jobs, hospitals, schools, and development. Today, only a small fraction of the local tribal population works in the mines—often in low-skill, unsafe roles without long-term benefits. Displacement is another harsh reality. Villages like Mechua and Telaitand were relocated to make space for tailing ponds—open pits filled with radioactive waste. These tailings often overflow during monsoon, contaminating local streams and farmland.

"Our land was fertile. Now nothing grows here. Even the cows have stopped giving milk," says Lakhan Murmu, a displaced farmer from Mechua.

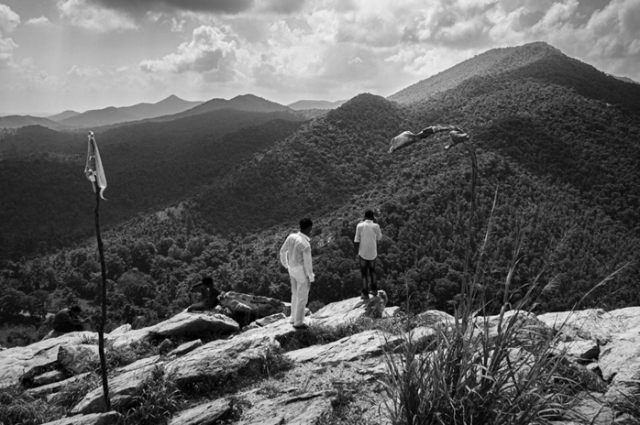

Photo by Subhrajit Sen

The hills of Jadugoda have been mined for uranium since 1967. Villagers argue that instead of developing lives, the oldest uranium mining region has witnessed extensive health and environmental damage.

Rising Resistance: A Struggle for Justice

The suffering has not been without a voice. Local movements like the Jharkhandi Organisation Against Radiation (JOAR) have been fighting for years to raise awareness, demand independent health audits, and seek justice for affected communities.

Protesters have faced harassment, arrests, and police violence. In 2014, activist Ghanshyam Birulee was detained for organizing peaceful protests. His crime? Distributing pamphlets demanding a public health inquiry.

These acts of suppression only reinforce the community’s growing belief that their concerns are being systematically silenced in the name of national interest.

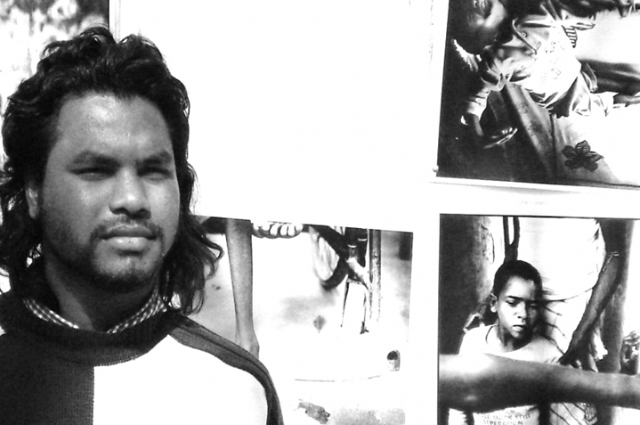

Photo by Uranium Film Festival: Ashish Birulee, son of Ghanshyam Birulee said "I saw my relatives die of radiation“

Another story of the ordeal is of Sushree Devi, a mother who lost two children to mysterious illnesses, which made national headlines. She is now a local face of protest. Her message is clear: “We were not consulted. We were not warned. And now, we are dying.”

What Has the Government Done?

The Indian government, while committed to expanding nuclear energy, has failed to adequately address or acknowledge the health and environmental costs of uranium mining in Jaduguda.

Existing Policies and Their Loopholes:

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) are often conducted with little community engagement and in languages the tribal people do not understand.

- Radiation safety norms exist but monitoring is weak, and data is rarely made public.

- Compensation and rehabilitation packages have been sporadic and insufficient.

The National Mineral Policy 2019 emphasizes “sustainable mining,” but doesn’t mandate independent audits or community health surveillance—key elements missing in the Jaduguda case.

Whose Development Is It Anyway?

“The earth does not belong to us; we belong to the earth.” – Chief Seattle.

At its core, the problem in Jaduguda is not just one of environmental neglect but of environmental injustice. The tribal communities never gave informed consent to live beside radioactive tailing ponds. Many don’t even understand what uranium is, let alone the risks it poses. This raises a fundamental ethical question: Can we call it development if the cost is paid with invisible lives?

The Adivasis of Jaduguda, who have preserved the forests and rivers for generations, now live on contaminated land. Their cultural connection to the land has been severed. What value does nuclear energy bring if it comes wrapped in silence and suffering?

Can Mining Be Sustainable?

While uranium mining is inherently linear, its systems can be made more inclusive, accountable, and minimally harmful. Here’s what must change:

1. Community-Centered Governance: Enforce Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), Translate and communicate mining risks in local languages using visuals and community meetings.

2. Transparent Health and Environmental Monitoring: Set up independent panels to conduct regular health screenings and radiation audits, Make all data publicly accessible and peer-reviewed.

Upgrade Safety Infrastructure: Use global best practices in tailing management and radioactive waste storage and prevent groundwater and soil contamination through sealed containment systems.

3. Support Alternative Livelihoods: Introduce forest-based enterprises, eco-tourism, and agricultural training to reduce dependence on mining.

4. Invest in R&D for Safer Mining: Use circular economy funding to develop less harmful extraction techniques and efficient tailing reuse methods. Need to monitor groundwater contamination and air quality consistently.

Conclusion:

Toward a Just and Circular Future

The circular economy is not just about closing loops in materials. It’s about closing the gap between policy and people, between development and dignity. The promise of a circular economy is powerful. But it cannot be built on sacrificed communities and contaminated soil. As India marches toward self-reliance in energy, it must also uphold dignity, transparency, and justice.

Jharkhand’s uranium mining crisis is not just an environmental issue. It’s a human story — of forgotten communities, invisible illnesses, and unequal progress. The people of Jaduguda are not anti-development. They are just asking for a future where their children can drink the water, grow crops, and live without fear. That’s not too much to ask. That’s the very essence of what sustainability means. If India truly wants to walk the path of sustainability, it must listen to voices from Jaduguda, see the lives buried beneath radioactive soil, and choose a model of growth that respects people as much as it pursues power.

Because circularity begins not just with recycling materials — but with rethinking values.