Photo by Kogulanath Ayappan on Unsplash

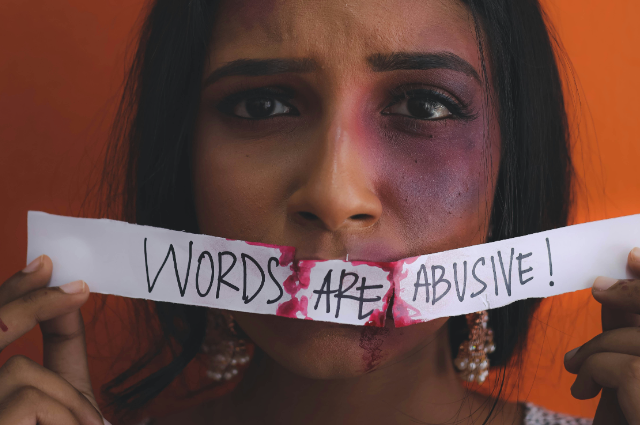

Kolkata, once affectionately known as the 'City of Joy', is rapidly acquiring a different reputation—one synonymous with fear, systemic failure, and the erosion of women's safety in public and private spaces. While the city was historically seen as a cradle of culture, intellect, and progressive thought, recent incidents have torn through that veneer, exposing the fragility of institutional protections for women. In a state where the Chief Minister herself is a woman, holding the dual mantle of head of state and Home Minister, many would expect women’s rights and safety to be top priorities. Instead, West Bengal finds itself mired in scandal, indifference, and outrage. Two particularly harrowing cases in 2024 and 2025—the brutal rape and murder of a young doctor at R.G. Kar Medical College and the gangrape of a law student on her college campus—have ignited public fury and revealed a chilling pattern of systemic rot, administrative complicity, and political inertia.

I. The R.G. Kar Medical College Case – A Murder Shrouded in Political Smokescreen

The morning of August 9, 2024, was like any other at R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital—until the body of a 31-year-old postgraduate trainee doctor was discovered inside a seminar room. The room bore the telltale signs of a heinous crime—upturned furniture, streaks of blood, and the stifling silence of unspeakable violence. The victim had been raped, tortured, and strangled. Her autopsy report ran four harrowing pages, detailing gruesome injuries: torn genitalia, scratch marks on her face, fractured thyroid cartilage, and bleeding from multiple orifices. Investigators noted evidence of 'genital torture' and 'perverted sexuality', phrases that made headlines and sparked widespread horror.

Sanjoy Roy, a 33-year-old civic volunteer attached to Kolkata Police, was arrested the following day. But within days, doubts emerged. Was Roy the sole perpetrator—or a convenient pawn? As student protests erupted and junior doctors across Bengal began a historic 42-day strike, many insiders claimed that Roy was merely a cog in a much larger and darker machinery.

These suspicions weren’t unfounded. By August 25, 2024, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which had taken over the case after the Calcutta High Court expressed lack of confidence in the Kolkata Police, raided the residences of former principal Sandip Ghosh and Vice-Principal Sanjay Vashisth. What they found was not only potential links to the cover-up but also financial irregularities amounting to crores. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) followed suit, launching its own investigation into hospital corruption. This was no longer a case of sexual violence—it had become a story of power, politics, and impunity.

II. The Law College Gangrape – When Justice is Locked Behind Campus Gates

Barely a year after the R.G. Kar tragedy, Kolkata reeled from another blow. On June 25, 2025, a 24-year-old law student from South Calcutta Law College was gang-raped on her own campus by an alumnus and two senior students. The prime accused, Monojit Mishra, was an ad-hoc professor and practising lawyer. The girl’s rejection of his romantic advances, and her refusal to betray her boyfriend were said to be the motive. Investigators later found a 1.5-minute video clip on Mishra’s phone, confirming the rape. Bite marks, nail scratches, and evidence of force were corroborated by her medical report.

More troubling than the crime itself was its setting—it happened in multiple rooms across campus: the student union office, a guard’s cabin, and a washroom. Each showed signs of a struggle. How was such violence possible in a functioning academic institution? The delayed response by the administration, the reluctance to report the case, and the hesitancy of police to act swiftly all pointed toward another systematic breakdown.

The arrest of the college’s security guard, Pinaki Banerjee, after CCTV footage showed him near the crime scenes further implicated the institution. Students and faculty alike have since spoken of an atmosphere of silence, fear, and institutional protectionism that allowed predators to act with impunity.

III. A Pattern of Violence – West Bengal’s Dark Recent History

The cases mentioned above are part of a disturbing pattern. Over the last five years, West Bengal has seen a spike in gender-based violence, many involving minors and students. In April 2022, a 14-year-old girl was gang-raped and murdered during a birthday party in Hanskhali, allegedly by a TMC leader’s son. Her body was forcibly cremated without post-mortem, destroying crucial forensic evidence. Public outrage forced the case into CBI hands.

In 2023, the Birsingha schoolgirl case saw another girl found dead under suspicious circumstances. Initial reports labelled it a suicide, but public protests led to a CID probe, which confirmed assault. Also in 2023, a girl in Nadia was raped by politically connected youths. Witnesses and families faced threats. The police delayed filing the FIR.

Each of these incidents reveals a clear pattern: when the accused have connections, investigations are delayed, witnesses silenced, and evidence tampered with.

IV. Political Patronage and the Crisis of Governance

Much of the blame lies in the politicisation of police and administrative services. With the Chief Minister controlling the Home Ministry, there is a dangerous overlap of political ambition and law enforcement. This has led to police officers hesitating to arrest politically connected individuals.

In many of these cases, FIRs were not registered until media and civil society protests escalated. When student doctors protested after the R.G. Kar incident, they faced threats of suspension. Journalists covering the cases were denied press passes. Families of victims reported harassment by local authorities.

Experts like retired IPS officer Arvind Roy have stated, 'There is no doubt political interference affects rape investigations in Bengal. Officers fear losing their posts or being transferred.'

V. The Culture of Fear in Academic Institutions

Once hailed as spaces of enlightenment, Bengal’s educational institutions are now becoming breeding grounds for silence, trauma, and unchecked abuse. Campuses that once birthed revolutions now silence their own students. From the suicides at Jadavpur University due to ragging and caste-based harassment, to the law college gangrape, the message is clear—students are not safe.

In conversations with current students (names changed for protection), we hear chilling accounts: 'We don’t report harassment anymore. Either they blame us, or we’re threatened into silence,' said a second-year student at the law college. A former RG Kar doctor said, 'We were told not to speak to the media. I know colleagues who were warned about losing their positions.'

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data for 2023 shows over 5,700 crimes against women in West Bengal’s educational institutions alone—an 18% increase from the previous year.

VI. Judiciary’s Role – The Last Line of Defence?

Amid institutional decay, the judiciary has emerged as a glimmer of hope. The Calcutta High Court’s intervention in the R.G. Kar case was crucial. It didn’t just transfer the case to the CBI—it condemned the 'unacceptable inertia' of Kolkata Police. Similar interventions happened in the Hanskhali and Nadia cases.

But systemic issues remain. Despite Supreme Court mandates, Bengal has few fast-track courts for crimes against women. Survivors are forced to relive trauma over the years of hearings. Conviction rates for rape remain under 25%, and trials often span over 3 to 5 years, eroding faith in justice.

Legal experts argue that until judicial reform is combined with police accountability, justice will remain aspirational rather than achievable.

VII. Recommendations and Urgent Calls for Action

- Establish Independent Police Complaints Authorities (IPCAs) in every district to oversee investigation delays, coercion, and mishandling of sexual violence cases.

- Fast-track courts with a 6-month mandatory verdict period for all rape and murder cases involving women.

- Mandatory safety audits of college campuses and hospitals every academic year.

- Whistleblower protections for faculty, students, and junior staff reporting crimes or administrative misconduct.

- Separate the Home Ministry portfolio from the Chief Minister to ensure impartial law enforcement.

- Digital surveillance enhancements in all women’s hostels, public hospitals, and university spaces.

- State-funded legal and psychological assistance to all sexual violence survivors from the point of FIR filing through trial.

- Ban re-employment of accused individuals in public or educational institutions until cleared by judicial process.

Conclusion: When the State Fails Its Daughters

These are not isolated tragedies—they are indictments of a broken system. They expose a culture where impunity thrives, where women are blamed, and institutions collude in silence.

West Bengal, a state that once nurtured luminaries like Kadambini Ganguly, the first female doctor in India, and Begum Rokeya, the pioneer of women’s education, now stands in the dock. The question is no longer whether change is needed, but whether there is the political will to enforce it.

Until then, the seminar rooms, libraries, and campuses of Kolkata will remain sanctuaries not of learning, but of fear.