The first time Ravi stepped into his local pharmacy in Mumbai, he didn't look for change or trend. He only looked for continuity. His uncle, a 62-year-old diabetic with heart complications, had required a weekly injectable medication. His blood sugar levels had finally normalized. But when he asked the chemist for the medication, he just shook his head in apology. "Sorry. But we are out of stock. Everyone wants that for weight loss nowadays." This was just a small incident in the local pharmacy. But what appeared to be a small incident was just a small part of a wave in the pharmaceutical industry in India. Here was a situation in which the suppression of disease was slowly overtaken by disease management.

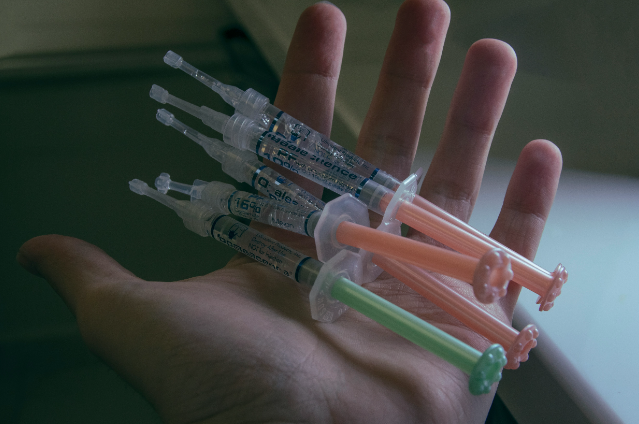

Semaglutide and tirzepatide are examples of drugs that are marketed worldwide under Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro, respectively. These medicines were not engineered as lifestyle boosters. They are designed for type-2-diabetes treatment and, subsequently, for obesity, both being chronic diseases that have profound metabolic causes. The International Diabetes Federation estimates that more than 101 million individuals in India are suffering from diabetes. This country was expected to be a natural beneficiary of these innovative drugs. However, these drugs have crossed a certain unseen threshold by 2024-2025, marking an interesting but questionable transition. These drugs are no longer perceived as pharmaceutical products but as a means of addressing social anxiety about weight, social appearance, and overall control over one’s body.

With the publication of clinical trial results revealing extreme average weight loss of up to 15 to 22% of those trial subjects’ body weight in some instances, the trial results spread in a manner that transcended peer-reviewed medical literature. “Before-and-after” pictures posted on Instagram, YouTube, and forwarded messages through WhatsApp did more to drive demand than would ever be possible at a convention for endocrinologists. “Medically-assisted weight loss” packages for upwards of tens of thousands of rupees a month for wellness clinics in Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru began circulating. By late 2025, Mounjaro would peak in sales to be the best-selling medication in India, clocking approximately ₹1,000 crore (or approximately $114 million) in sales, which is an unprecedented level for a new medication barely a handful of months in the market.

But the tsunami brought some challenges along with it. Internationally, a manufacturing bottleneck occurred for semaglutide since demand skyrocketed within the US and European markets. India, where imports were controlled, and only a certain amount was manufactured locally owing to intellectual property protection, faced this problem remarkably soon. At pharmacies, distributions became controlled. For new patients diagnosed with diabetes, doctors were put off starting treatment. Some hospitals “quietly started catering to people who could afford the drug on their own,” or observed the cost double or triple on the black market. A diabetologist at a national daily in Chennai claimed that his patients were missing doses or extending the period between injections from a week to every fortnight since they could not find a regular source. But a parallel world was at work. Young, otherwise healthy professionals began to inject the drug with limited oversight, and referrals came from cosmetic clinics, not hospitals. Bariatric surgeons and endocrinologists assessed that the sudden weight loss without sufficient protein or observation may cause the patient to lose muscle, have breakthroughs in hormone levels, and have gallbladder problems and psychiatric problems. There were reports of vomiting, lightheadedness, and very painful stomach symptoms, but this was outweighed by the success stories that proliferated on the Internet. Aspiration is rarely a patient.

As demand grew, there was a subtle, but definitive, shift in the priorities of Indian pharma. Boardrooms started asking not how such treatments can be made an integral part of diabetic care in India, but how soon market leadership can be achieved. The marketing budgets shifted to private practices, to urban India. But public practices remained restricted, mainly because of pricing, which was between ₹15,000 and ₹25,000 per month, beyond the means of ordinary Indians. The contradiction lies in India being a source that provides low-priced generics to other countries when it itself was unable to provide this critical drug to its own vulnerable populace.

However, complexities in the matter created another issue. It became an issue because patenting ensured that Indian companies could not freely produce generics for the local markets, despite exports having been made permissible in some cases. However, the irony in the matter arose when India became the origin for the production of GLP-1 medications meant for exports. An observation could be made that, despite differing views about the matter, priorities were the same. The cost of this disparity was paid in full by real humans. In Pune, a schoolteacher with previous cardiac ailments had to change her medication, as she needed the injection she was prescribed, which was no longer available in the market. In Gurugram, a 28-year-old software engineer, taking this drug to reduce his weight ahead of his wedding, was hospitalized because he took it from the internet, leading to dehydration. Such cases are never included in the shiny pamphlets but are the hidden face of this growth.

The problem is not the drug itself, but the underlying problem that the drugs represent. From a scientific standpoint, the GLP-1 class of drugs represents the most notable breakthrough in metabolism for several decades. The problem lies in the manner in which the healthcare story in India has bent to the market consensus. A drug that symbolizes "discipline, beauty, and success" shifts the system that delivers those drugs to serve the consumer, rather than the patient. However, is now the time when the course can still be changed? With patent rights expiring and new licensing deals in the next few years, Indian pharmaceutical firms could be allowed to develop cheaper alternatives, and this will greatly increase accessibility. However, this will not just happen by itself. If not, history will just repeat itself: innovation will come with hope, but will soon be in the hands of those who have more buying power. Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk are staking a lot in India, and they are right in doing so.

The country is at the crossroads where a huge burden of disease meets huge consumer aspirations. However, one must not confuse success in commerce with success in health. When control trumps cure, one realizes what values the system upholds. Ravi finally found his uncle's medication after dialing six pharmacists and paying extra for it. Many others are not this lucky. The question India faces today is an easy one but an unpleasant one: Will the next discovery in medicine be viewed as a public good or a luxury item? India's response to this question will set not only the way these medicines are remembered but also India's story within healthcare—whether it's one of healing or of who has mastery.

Sources:

- Briefing, I. (2025, November 14). Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro becomes India’s Top-Selling drug: Market view. India Briefing News. https://www.india-briefing.com

- Ellis-Petersen, H. (2025, December 21). India’s doctors sound alarm over boom in availability of weight loss jabs. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com

- ET HealthWorld & www.ETHealthworld.com. (2024, September 3). Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic shortage expected to continue into Q4. ETHealthworld.com | Pharma. https://health.economictimes.indiatimes.com