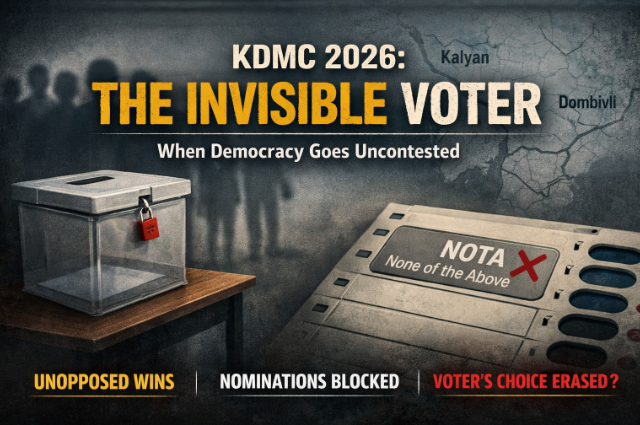

When 20 candidates in the Kalyan-Dombivli unicipal Corporation (KDMC) were declared winners unopposed in January 2026, it looked like a political triumph for the Mahayuti alliance. What it should have looked like and what voters and lawyers now insist it was: a procedural blackout. Voters were deprived of even the possibility of rejecting the lone name on the ballot by pressing NOTA (None Of The Above). The result is a paradox: no law changed, yet the practical effect was to silence a ballot box. How this happened is not complicated; it is methodical. Out of 122 KDMC seats, 20 were decided without any contest—14 by the BJP and six by the Shinde-led Shiv Sena—after rival candidates either had their nominations rejected on procedural grounds or formally withdrew by the close of nominations on January 1, 2026. The wave of last-minute exits and rejections was concentrated enough to hand Mahayuti nearly 16% of the corporation before a single vote was cast.

What makes the KDMC episode statistically unusual is not merely the number of unopposed seats but their geographic concentration and timing. Of the 20 unopposed wins, a disproportionate share emerged from Dombivli East–West panels and select Kalyan wards, meaning entire neighborhood clusters lost the chance to vote rather than isolated pockets. Nearly one in six seats (16.39%) of the Kalyan-Dombivli Municipal Corporation were decided without polling, where unopposed wins were historically rare and scattered. Crucially, a majority of opposition withdrawals and nomination rejections occurred within the final 48 hours before the January 1 deadline, compressing decisive electoral change into a window too narrow for voter awareness, scrutiny, or legal remedy.

Local incidents illustrate the pattern. In Ward 28A, Harshal More—son of MLA Rajesh More—and in Panel 24, where Ramesh Mhatre, Vishwanath Rane, and Vrushali Joshi were declared winners, the opposition’s footprint simply vanished as nomination forms were pulled back or invalidated. Several prominent withdrawals, including MNS Dombivli city president Manoj Gharat, cleared the path for uncontested wins that, on paper, looked clean but in practice left voters without a choice.

Opposition leaders call these exits coerced or bought. Shiv Sena (UBT) MP Sanjay Raut alleged that “bags of cash” figures as sensational as ₹5 crore per seat have been claimed in public statements and were used to pressure rivals out; others described phone calls from ministers and the involvement of local muscle to persuade withdrawals. Whether money changed hands is a matter for criminal and electoral inquiry, but the qualitative effect is the same: the field was cleared at the last moment.

On the institutional side, the State Election Commission (SEC) has publicly acknowledged the abnormality and said it will scrutinize contested unopposed wins before certifying them, asking municipal officials for inquiry reports into allurement or coercion. That response is significant because it admits the possibility that administrative processes—rejections by returning officers, the timing of notices, or the handling of technical defects in nomination papers—can be used as instruments of political engineering even where the statutory framework remains unchanged. That admission matters to a legal question at the heart of the controversy: does an unopposed candidate automatically deprive voters of their right under law to register dissent through NOTA? The argument pressed by activists and opposition parties is straightforward and constitutional in tone. They note (1) the Supreme Court and the Election Commission have treated NOTA as a voter-choice mechanism where applicable; (2) municipal bodies and state election regulations cannot, by administrative convenience, extinguish that mechanism; and (3) when the competitive aspect of an election has been artificially eliminated, courts must consider whether due process and the constitutional right to vote remain meaningfully protected. A public interest litigation pressing these questions is already slated for hearing in the Bombay High Court.

What complicates the legal terrain is that Indian election law is a blend of constitutional guarantee and procedural rules. Article 326 guarantees the right to vote at parliamentary and assembly elections, but local body elections sit in a mixed space with state statutes and SEC rules. There is no clear, universally binding statutory provision that says a single candidate must be put to a NOTA vote for local bodies, nor is there an express prohibition against declaring a lone candidate the winner. The absence of a black-and-white rule is precisely why judicial scrutiny matters now: if the process that produced unopposed candidates was tainted by coercion or by differential application of technical rules, courts can (and should) treat the declaration of winners as premature. The SEC’s pause to seek inquiry reports is a tacit recognition of that legal vulnerability.

Beyond courtroom subtleties, there is a practical democratic cost. The 27 Villages Struggle Committee, a local movement pressing for a separate civic body and long-standing grievances over neglect, called for an election boycott in several panels; their abstention, whether principled or tactical, further thinned contestation in wards where civic discontent was highest. Boycott or withdrawal, whether voluntary or induced, amounted to handing de facto veto power over the ballot to the candidate who stayed on. In other words, the mechanics of nomination and withdrawal became the new ballot.

What should happen next is clear in democratic terms if not in statute: rigorous, time-bound inquiries into alleged allurement and coercion; transparent publication of the reasons for each nomination rejection; and judicial guidance on whether, when a single candidate remains, elections should nevertheless allow a NOTA count that can trigger re-polling or other remedial measures. The Bombay High Court hearing on NOTA in unopposed local-body elections offers the first realistic forum to convert those democratic expectations into enforceable rules.

If courts and election authorities do not act, the KDMC episode will stand as a template: keep the law unchanged, manipulate the paperwork and the last 48 hours of nominations, and you can produce a mandate without a vote. The real fix is not new rhetoric but a procedural guardrail: require electoral authorities to treat unopposed returns as provisional until a NOTA option is tested, or at minimum publish a statutory rule that clarifies when and how NOTA applies in single-candidate scenarios. Anything less risks converting the right to vote from a lived constitutional guarantee into an optional ritual. The invisible voter, once erased, is hard to get back, but restoring the choice to the ballot would be an essential first step. A democracy that allows mandates without ballots does not fail loudly. It fails quietly—one unopposed seat at a time.

Sources:

- Mendonca, P. K. G. B. (2026, January 3). Maharashtra civic polls: 39 Mahayuti candidates win unopposed across 4 bodies, raising opposition hackles; SEC to scrutinize. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- Ians & Ians. (2026, January 3). Maharashtra Civic Body Elections 2026: Democracy is being bought with bags of cash, says Shiv Sena MP Sanjay. Free Press Journal. https://www.freepressjournal.in

- Badgeri, P. K. G. (2026, January 4). ‘Why only Mahayuti candidates?’ Opposition cries foul over “68” unopposed wins in Maharashtra civic polls; claims Rs 5cr bribes, threats. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- Zee 24 Taas. (2015, October 10). Kalyan : 27 villages boycott the KDMC election [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com