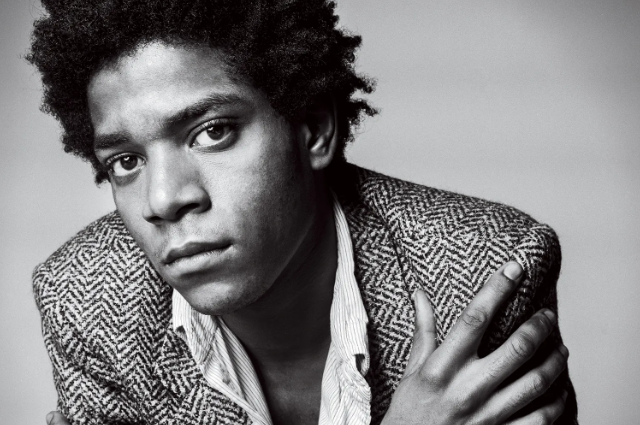

Some are born. Some are made. And then there are those rare few artists who burst in like lightning, incandescent, wild, and gone before they can even growl. Jean-Michel Basquiat was one of the latter. A street kid of New York, a king wearing a paper crown, a prophet with paint-splattered palms, Basquiat did not merely create art; he detonated it. He ripped it apart and remade it from his own body, language, and blood. Amid the graffiti-covered subways of 1980s Manhattan, where hip-hop was taking birth and punk rock was howling from the sewers, Jean-Michel Basquiat was already myth-making. He initially appeared as a ghostwriter of a kind, writing cryptic, poetic messages all over lower Manhattan under the tag SAMO© (short for "Same Old Shit"). His graffiti wasn't graffiti; it was anti-graffiti, existential puzzles in felt-tip ink: "SAMO© as the end of mindwash religion, nowhere politics, and fake philosophy." SAMO©" To the passing commuter, it may've appeared as urban white noise. But to those who stopped, there was an otherworldly enchantment to it. It was like the city was attempting to communicate.

Born in 1960 in Brooklyn to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat was raised at the crossroads of languages, histories, and geographies. He learned to speak French, Spanish, and English by the time he was ten. His mother, Matilde, brought him to museums, MoMA, and the Met before his feet could even touch the ground from the subway seat. Then he met with an accident, a car crash, when he was seven. In the hospital, recovering, his mother gave him a copy of Gray's Anatomy, a perpetual fascination. That anatomical accuracy, bones, skulls, hearts, and intestines, would pulse through his canvases like a second heart. That wasn't about structure. It was about what's underneath the skin. That became his lifetime theme.

But Basquiat was not constructed to be a museum rat or gallery darling, at least not initially. He ran away from home as a teenager, cycling in and out of homelessness, couch-surfing across Manhattan, and painting on doors, sweatshirts, and discarded scraps of paper. He played in a sound band named Gray. He sold hand-painted postcards to Warhol before becoming friends. He slept in Washington Square Park and painted in whatever room would accommodate him. And then, something occurred.

The 1980s were a neon blitz. Reagan's America was hardening its edges. Wall Street was taking off. MTV was launching. And the art world? It was hungry for rawness, an antidote to the clean coolness of conceptual and minimalist art that had reigned supreme in the '70s. Basquiat's paintings were brutal symphonies of colour and disarray. They blended image and text, past and popular culture, and violence and play. He painted kings and martyrs, boxers and saints, and jazz musicians and saints, all together in the same body. He painted as if he were possessed, slashing words across his paintings: "SICKLES," "ORNITHOLOGY," "DIZZY GILLESPIE," "SOAP," "SUGAR RAY ROBINSON," and "X-RAY." They weren't incidental. They were messages. Memory. Black history. Anatomy. Colonialism. Class war. All thrown together in a scribble that was both childish and precise. And the art world went berserk.

He was the youngest artist to ever be invited to the Whitney Biennial. He partied with Madonna before she was famous. He was featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine at age 22. Collectors who used to cross the street to get away from him now toasted champagne glasses beneath his paintings. But fame is a double-edged can of spray. Basquiat also became friends with Andy Warhol, then considered passé by the New York art scene. They produced a series of joint works in which Warhol's clean logos and silkscreens fought with Basquiat's swirling lines and symbols. The collaboration was met with scorn from many critics, who accused it of being exploitative. Others accused Warhol of tokenising Basquiat; others accused Basquiat of riding Warhol's coattails. The truth, as always, was more nuanced. Basquiat once told us that he was "not a Black artist. I am an artist." But he also stated, "Every single line means something." Race haunted his work. Haunted him. In a white-dominated art world, Basquiat was frequently made into an exotic genius, primitive, wild, and untamed. The same critics who lauded his "rawness" could not discern the fierce intelligence behind it. He devoured books on anatomy, African history, and semiotics. He incorporated philosophy, politics, jazz, and street culture into each work. He painted Black heroes, boxer Joe Louis, jazz great Charlie Parker, and the saints of his own pantheon, not as saints but as battlegrounds. Their crowns were always cracked. Fame consumes. It always had. The art world craved Basquiat: more exhibitions, more paintings, more performances, and more interviews. But he was incinerating internally. Friends claim he painted with some kind of madness, frequently through the night, under the influence of heroin and heartbreak. With Warhol's unexpected death in 1987, something in Basquiat cracked. In August 1988, at the age of only 27, Basquiat died from a heroin overdose in his studio on Great Jones Street. The kid who scrawled secret messages on city subway walls in his name is buried in Brooklyn. His gravestone carries only this inscription: "Jean-Michel Basquiat, Artist, 1960–1988.

But he was also more than an artist. He was a mirror held to America's racial sores, a sage of street scripture, and a reminder that disorder, too, can be holy. Now his works sell for more than $100 million. His face adorns T-shirts, his art decorating album covers. Beyoncé and Jay-Z dressed up as him and Warhol in a Tiffany commercial. His works hang in premier museums, and his name is on the lips of every young art student who has a can of spray paint and something to yell. But here's the thing: Basquiat is not a brand. He is a bruise. A brilliance. A question. And his work continues to ask: Who gets to be a genius? Whose history gets remembered? Whose body is on display, and for whom? He wore a crown. Not because he was egotistical, but because he had to. In a world that tried to erase Black brilliance, Jean-Michel Basquiat made himself visible, loudly, defiantly, messily. And in the process, he made the world look back. "I cross out words so you will see them more. The fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them."

Jean-Michel Basquiat, and we're still reading, still learning, still pursuing that lightning.

Originality of an artwork does not exist in a vacuum. Art, as language, is rehashed, recycled, and reimagined. Originality is not so much something new as it is old components in a new relationship. We perceive something novel, something new, but truly, what we are perceiving is a new relationship. The artist is the creator of new contexts, not new objects. Not only was Basquiat's painting new for its time, but the artist himself, being an African-American, was unusual to the art community. But is fame acceptance? Is it recognition, proper recognition? We all wish for these things; we all want to see them in our own worlds and in the larger world. But to be different is to be alone, and to be recognised as different is to be alone again. This paradox of individuality and solitude raises questions about the true nature of success in the arts. While some may celebrate the visibility that comes with fame, others may find that it amplifies their isolation, leaving them grappling with the complexities of identity and belonging in a world that often values conformity over uniqueness.